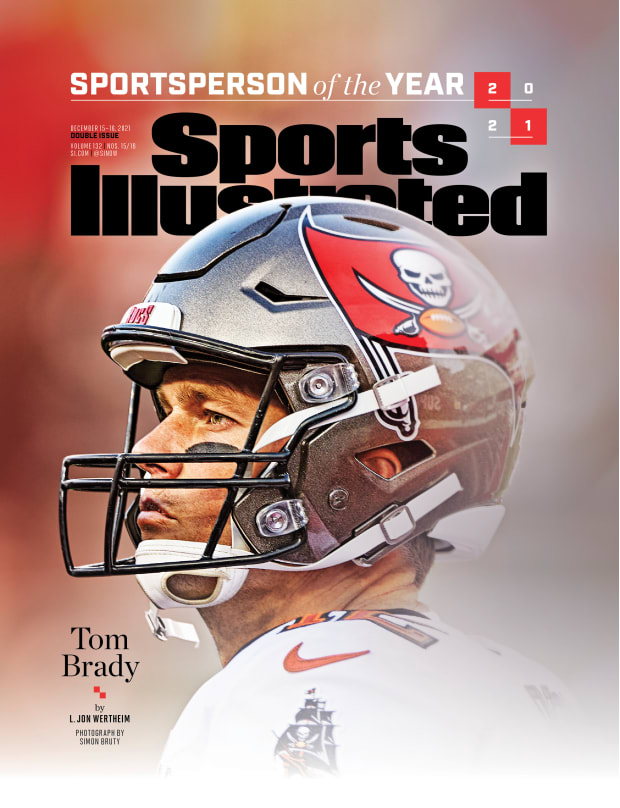

The quarterback earns this honor for the second time, 16 years after the first, for a year defined by victory in Super Bowl LV and—in the midst of an MVP-caliber encore—victory over time itself.

Age is just a number. But that number is on the move, and longevity is on its way to running up the score. According to the United Nations, in 1990 there were 95,000 people on the planet who made it to 100. Today there are more than 500,000 centenarians, and, by 2100, it’s projected there will be more than 25 million. In 1980, around 382 million people were 60 and older. By 2050, that number will exceed 2 billion. There are some gerontologists who believe the first person to live to age 150 has already been born. Others ask: Are we so sure there are age limitations on human life?

What are fun facts and dinner-party conversation starters for us are foundational to the School of Aging Studies at the University of South Florida. It’s the largest—and, appropriately, one of the oldest—school of its kind in the country. Its mission statement cites a commitment to “understanding the biological, psychological, social and public policy aspects of aging.” But talk to faculty casually and it’s clear that one of the core principles of the curriculum is this: to teach life hacks that help human beings get older with grace.

Located as it is in Tampa—the U.S. metro area with the densest concentration of senior citizens—the school has always had plenty of subject matter and data points nearby. But now, the campus is also within a golf-cart drive of the archetype for aging gracefully. Want to conduct a field study to see what longevity looks like in practice (not to mention in games)? Well, Tom Brady lives and works just a few miles away.

For all his manifold football gifts, Brady’s true superpower is his ability to take time, stretch it out like the resistance bands he uses and then double it back. For the 44-year-old, time is a construct, measurable by ways other than revolutions around the sun.

“I’d say there are parts of me that are 55, and I think there’s parts of me that are 25,” says Brady. “What parts? I think I’m wise beyond my years. I think I’ve had a lot of life experience packed into 44 years. When I go through the tunnel and onto the field? Probably mid-30s—and I’ve got to work really hard to feel good. It’s a demolition derby every Sunday. I feel 25 when I’m in the locker room with the guys. Which is probably why I still do it.”

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

Order the 2021 Sportsperson of the Year Issue

He explains this theory of time on a warm Tuesday in November. He’s seated inside a Tampa yacht club—he’s not a member, he’s quick to point out—that looks out over Hillsborough Bay and is convenient to Brady’s home. He has risen early this morning (of course). Walking with energy and purpose he enters the main dining room carrying a water bottle the size of a fire extinguisher. He is wearing designer sweats and a big, warm smile that makes his teeth look like a row of white iPod Nanos—kids, ask your parents—aligned perfectly inside his square jaw.

Back to time: How the hell is he still doing this, volunteering for those weekly car crashes for months and months, well into his 40s? It’s complicated. “It’s not like I wake up every day, like, Hey, man, it’s another sunny day!” says Brady. “No, it’s like, All right, let’s grind and move on.” Then he quickly adds, “There’s still joy. The competition’s fun and, uh, you know, I’m still pretty good at it, too.”

There’s also the specter of the alternative: “I imagine not playing. And I imagine watching football on Sundays going, These guys suck. I could do way better than that. And then still knowing in my heart that I actually could still do it. If I stopped, I think I’d have to find something else that I’m pretty good at. And I don’t think that, you know, I’m going to be able to jump into something that has the same amount of excitement.”

So long as that’s the case, so long as he can continue finding fulfillment, Brady will play on, thanks. He’s fond of a phrase that suggests continuity, one that befits someone so committed to hydration: Why not keep drinking?

If, in the manner of Brady’s career, we want to extend that analogy: It’s not just that he is still drinking; he is chugging. And there’s no indication he’s near the bottom of the glass. He is at an age when even the finest of his peers are beyond their prime. Roger Federer (40), Serena Williams (40), Albert Pujols (41), Tiger Woods (45). Titans all, but not acclaimed for their athletic achievements in 2021.

Then there is Brady. Still pretty good at it warrants a 15-yard penalty for flagrant understatement. He continues to discharge his duties with his customary, clinical excellence. He still throws with precision and maneuvers deftly in the pocket. Maybe more than ever, he maintains command of himself, and by extension his team, projecting comfort, evincing poise when it matters most. And he is still winning.

Brady started the year by piloting his new team, the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, to five straight wins, one to end the 2020 regular season and four in the playoffs. The culmination came on Feb. 7, when Brady started his 10th Super Bowl. He walked away with his seventh ring and was named Super Bowl MVP for the fifth time, leaving his heel print on yet another NFL season.

Early in the offseason Brady flew to Los Angeles and “cleaned up” (his phrase) his left knee. In this season, his 22nd, he has turned in some of the most brilliant shifts of his career. Brady leads the league in touchdown passes (34), the unprecedented 600th of his career coming in October, and the Bucs lead the league in scoring (31.4 points per game). His team is 9–3, and Brady is among the favorites to be named MVP. And he has already, officially, taken this honor: Tom Brady is the 2021 Sports Illustrated Sportsperson of the Year.

Brady, this year, is the recipient of the 68th annual SOTY. He also—mind the gap—won the honor in its 52nd year. That was for his excellence in 2005, a time when cars ran only on gasoline, squarely in the flip-phone era. How long ago was this? In the SI article celebrating Brady there is a reference to his posing once while holding a goat. And it’s describing a bizarre photo shoot—not nodding to the GOAT, the honorific that now, of course, accompanies most mentions of Brady.

Titled “The Ultimate Teammate,” the story praises Brady for his work ethic (“You can see his innate ability to carry the logic of practice to the conclusion of a game”) and his commitment to incremental improvement (“the grinding work of constructing football excellence that pays off in the public performance”). Brady, then in his 20s, speaks cautiously but describes his passion for football: “I love it so. Just running out there in front of 70,000 people.” Also, his sheepishness about standing out: “I don’t need to be the showstopper, the entertainer. I’d much rather people assume I’m one of the guys.”

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

Here, in 2021, Brady’s coach, Bruce Arians, takes inventory of his quarterback, reeling off a string of superlatives but landing on a familiar turn of phrase: “He is the ultimate team player.” To a man, the Buccaneers describe Brady being “down to earth.”

Brady is, you might say, committed to the role. His organizing football principles are largely unchanged. Same for his leadership traits and his character. And yet in other ways Brady is a much different man than that 28-year-old bachelor. Handed the cover from 2005, he smiles. “I think I recognize that person,” he says. “But there’s so much more to me now.”

He is the best-ever practitioner of the most important position in his sport—perhaps in all sports. But let’s be clear: This award is not for lifetime achievement but based on Brady’s body of work over the last 12 months. This is not an aging athlete admirably hanging on. This is an athlete who may never have performed better.

It happened not even two years ago and already it carries a historic ring, cemented into those hinge-point New England moments, deserving of its own shorthand, right up there with “Revere Rides Through Town,” “Tea Dumped in Harbor” and “Sox Exorcise Curse.” And, for that matter, from fall of 2001: “Backup QB Brady Thrown Into Fray.”

On March 16, 2020, as COVID-19 was just ramping up in the U.S., Brady drove to the home of Patriots owner Robert Kraft to make official what he had decided privately months before. As Brady recalled to Howard Stern, “I was crying. I’m a very emotional person.” After 20 unbroken years with New England, “Brady to Become Free Agent.”

Brady didn’t arrive at the decision easily. He knew well that this stay-or-go athlete dilemma tends to yield mixed results. The player with whom he always will be bracketed, Peyton Manning, left Indianapolis for Denver, won a Super Bowl and never played another NFL down. That was nearly six years ago. The day Brady won his first Super Bowl, in 2002, Michael Jordan was playing, unmemorably, for the Washington Wizards. And Brady still winces when he recalls when, as a teenage 49ers fan in San Mateo, Calif., he learned that his idol, Joe Montana, was decamping late in his career to Kansas City.

Two days after Brady met with Kraft, Arians sat in his home with Bucs general manager Jason Licht. For months they had been running point on a recruiting mission they called Operation Shoeless Joe Jackson. (Field of Dreams . . . get it?) That afternoon Brady called Arians, who passed the phone to Licht, who recalls that when Brady began the conversation, “Hey, babe,” it was safe to assume the Buccaneers had their man. “It was a phone call, and it was during COVID,” says Licht. “But it was one of the biggest moments in franchise history.”

First came the yuks. Brady was going to Florida, because . . . Florida. Where else do well-preserved Northeasterners go when it’s time to throttle back? Then came the cynicism. Brady was availing himself either of the state’s lack of personal income tax or the congenial weather or the Buccaneers’ soft expectations. Here was a franchise that, pre-Brady, had an all-time winning percentage of .386 (267-424-1), the worst of any major men’s U.S. pro team.

Brady, though, is nothing if not a pragmatist. Tampa was a market with low-intensity lighting, and still a short flight away from his son Jack, who lives in New York City. Brady is also a football pragmatist. He saw a team with a loaded defense, exceptional skill-position players and sturdy offensive line. He also saw the opportunity for an invigorating culture change. Arians, 69, was born within six months of Bill Belichick but cuts a different figure—enjoying, as he does, laughter, self-deprecation, motorcycle rides and a reputation as perhaps the least autocratic coach in the NFL.

But that was only the start. Brady laughs as he plays the compare-and-contrast game: “different conference, different division, different coaches, different offense, different terminology, different players, different drive to the stadium.” Determined that the divorce remains amicable, Brady gently reroutes conversation about the Pats. But this he will say: “Our team here, I think there are more voices. And it’s fine. There’s different ways to be successful.”

With Brady, the Bucs started out 7–5. In New England this might have marked a crisis. (“Belichick always had a saying,” Brady recalls. “When you win, your quality of life is better for everybody.”) In Tampa it did not. The COVID-19-constricted season was supposed to be one of transition for the Bucs; in 2021, they would really be a cohesive unit. But then Tampa Bay didn’t lose another game the rest of the season.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated (2)

Before Super Bowl LV, Brady recognized a sort of power imbalance. He had played in more big games than the rest of his teammates, combined. So he sent a blizzard of texts to them. Some were sent individually, some to a group. Some contained motivational saws (process over perfection); some were concrete instructions about schemes or observations that Brady had picked up while watching film of their opponent, the Chiefs.

Licht recalls that hours before the game he took time to try to savor the moment, to drink it all in, as his quarterback might put it. One season earlier Tampa Bay was 7–9 with an offense piloted by Jameis Winston; now, with Tom Friggin’ Brady under center, the Bucs were in the Super Bowl. The game was at Raymond James Stadium (even if cardboard cutouts filled two-thirds of the seats); no other host team had ever played in a Super Bowl. Brady noticed Licht, walked over, sat down beside him on the bench, smiled his smile and said simply but firmly, “Jason, it’s going to be a great day.” And it was.

Ask Brady about a singular moment from the game and he strokes the light stubble on his chin, trying to come up with something specific. The defense played well; the opponent did not. Brady was at his Brady-est; his best plays didn’t stand out in the way they do for other star quarterbacks, but the ball always got where it had to be with virtually no mistakes. Unflustered and unhurried, he completed 21 of 29 and connected with his old buddy, tight end Rob Gronkowski, for two of his three touchdowns.

Tampa Bay, a three-point underdog, prevailed, 31–9. In the weeks before the game, Brady strenuously—and probably wisely—avoided the obvious story line, the one that traced back to New England. Arians did not. “Tom is playing for his teammates right now,” Arians told SI in January. “I think personally, too, he’s making a statement. You know? It wasn’t all Coach Belichick.”

Brady recalled the postgame scene after the Patriots won Super Bowl XLIX in 2015: “We had beaten Seattle and we flew home to Boston, and I came home to a house that was flooding. I mean, literally, I had a broken pipe and I had a waterfall coming down. And that night you thank God. It’s so glorious the night after a Super Bowl. [But] the reality? I got to fix this leak in my house.”

Mark J. Rebilas/USA TODAY Sports

In a sense it was a healthy reminder that the real world happens, even to Super Bowl MVPs, so it’s important to savor the moments before the pipes burst. Now it comes to him: The highlight of that night, of Super Bowl LV, was when he brought his family—his wife, model Gisele Bündchen; their kids, Ben, 12, and Vivian, 9; and Jack, 14, Brady’s son with actor Bridget Moynahan—onto the field to celebrate.

That Brady was—and is—a winning football player makes for something other than a news flash, especially for the men who recruited him to Florida. Even so, both Arians and Licht marvel at the full force of the Brady Aura.

Arians tells the story of watching Brady lead an early informal workout with tight end O.J. Howard and wide receiver Scotty Miller. Arians had recently told both players about the need to pump their arms on their routes. When they didn’t, Brady also noticed and pointed it out to his two teammates.

Says Arians, “They look at me [when I tell them] and go, Oh, O.K. And when Tom tells them they go, O.K., Tom! And they do it.” Arians then cackles, thinking of other messages he would let Brady communicate to players on his behalf. “He tells ’em to do it, and they listen!” (Pause for a thought exercise: Imagine Brady’s previous coach joking about delegating some of his duties to the charismatic quarterback.)

Brady may have, like the rest of us, binged The Last Dance—“That’s my era!”—but his leadership style is at striking odds with that of the basketball GOAT. Michael Jordan demanded that his teammates match his intensity and humiliated those who couldn’t handle his lacerating edges. Brady is all soft power. Teammates should feel seen and heard. Gaps in accomplishments and fame—and commitment levels—among players must be bridged. Experience is something to be shared.

Licht laughs when Brady introduces himself warmly to rookies and new teammates by saying, “I’m Tom Brady.” No s---, you’re Tom Brady. But the message is clear, as is the effect. “Tom is known as the greatest player of all time, and I get the sense they were expecting him to come in and want preferential treatment and have an ego—which would be well deserved,” says Licht. “But he just wants to be one of the guys. He wants to earn their respect. And they think, I don’t want to let this guy down. We all think that.”

Early on Brady issued a request to his new center, Ryan Jensen. Could he apply baby powder to his backside to keep the football free of sweat? Jensen complied, then walked around the field trailed by chalky plumes, as if he were announcing the new pope. Before it could be a source of embarrassment or teasing in the locker room, Brady spoke to teammates to make sure it was taken as instructional: These are precisely the kind of small sacrifices and adjustments you make when you are fully committed to winning.

More than ever Brady is surrounded by teammates who entered the league with more fanfare. Mike Evans, his favorite downfield target, was the seventh pick in 2014. Tampa Bay’s top running back, Leonard Fournette, went fourth in ’17. Even Brady’s backup, Blaine Gabbert, was the 10th choice in ’11. Two decades after he left Michigan, Brady’s modest draft slot of—all together now—199, still galvanizes him. “He had to work for everything,” says Arians, “and he just never, never lets himself forget that.”

But the coach noticed something else: Brady has taken a source of personal motivation and alchemized it into something to benefit his teammates. What was once about—to use the tired trope—proving the doubters wrong has evolved into, Guys, if I can go from good to great, you sure as hell can, too.

It’s hard to exaggerate just how statistically outlying Brady’s longevity is. The NFL’s next-oldest player is Rams offensive tackle Andrew Whitworth, who will be 40 on Dec. 12. Brady is closer in age to Dan Marino, who played his last game in 1999, than he is to Chiefs quarterback Patrick Mahomes. Nearly half the NFL’s coaches—13 of 32—are younger than he is. (Though Brady’s own coach, pointedly, is the league’s third-oldest.)

Keep going? Brady is older than 59 members of Congress. On that fateful day in 2000, when 198 other players were summoned into the NFL workplace ahead of Brady? Bill Clinton was president. There have been six presidential elections since. Remember, too: Brady’s longevity-to-the-point-of-absurdity is coming in pro football, a sport in which careers are notoriously nasty, brutish and short. And there hasn’t been any sign of falloff.

That’s not just the eye test; advanced statistics bear it out too. Arians’s offense attacks deeper than most—no risk it, no biscuit being the operative phrase. In 2020, Brady’s air yards per intended pass, a measure of how far downfield a quarterback throws on average, jumped to 9.3 yards, a 22% increase from his last season in New England. Yet, despite the higher degree of difficulty, his completion rate also rose, from 60.8% to 65.7%.

He’s doing it at a time when defenders have become freakish in their own right. From 2000 to ’03, Brady’s first four seasons in the league, 10 defensive linemen clocked in under 4.7 seconds in the 40-yard dash at the NFL’s scouting combine. Over the past four years, 41 have done so. That has led to an emphasis in athleticism among the new class of quarterbacks. Indeed, according to Next Gen Stats tracking data, through Week 12 of the 2021 season only Steelers vet Ben Roethlisberger was covering less ground per play (7.2 yards) than Brady (8.0).

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

Retirement has its appeal—golf, time with the family, business opportunities—but it is outstripped by the lure of continuing to work. And so it is that Al Michaels, 77, the voice of NBC’s Sunday Night Football, has consulted with and confided in Brady. Their pregame broadcast production meetings, once filled with football shop talk, now veer toward weightier topics and shared experiences. Says Michaels, “When I see Tom, I think, Damn, you can go at that level no matter what you’re doing, and I feel like I can. It’s just a cool thing, the kind of symmetry.”

Michaels isn’t alone in finding inspiration in Brady’s longevity. UFC fighters, European soccer players, pro golfers, athletes of a certain maturity—they all try to see some version of themselves in Brady and come seeking his counsel and inspiration. Comb social media and you’ll find teachers crediting Brady with their decision to get back in the classroom, pilots referencing him when they decided to stave off retirement.

Even though serving as a standard-bearer for manipulating time only adds to his pressures, Brady welcomes the opportunity. “If people want what I want, then I’m there to help them,” Brady says. “If they don’t? All right, let them do their own thing. No problem. But if you come to me and you say, ‘Hey, how can I have a career like yours?’ I’d be very happy to help anybody.”

At the same time Brady readily admits that he holds no secrets; he, too, looks to others. His wife. His parents. Towering athletes—Montana, Jordan, Steve Young—who came before him. But he also turns to a sort of council of elders, who’ve lived well and lived long. Ageless Tom Brady might work alongside teammates half his age, but he often socializes with men twice as old, many of them successful entrepreneurs or titans of industry. They neither want nor need a selfie or comp tickets or the nimbus of Brady’s celebrity. These friendships come without the whiff of transaction.

The tribal elder in this circle might be Sam Reeves. Armed with a wealth of stories he tells in a slow Southern drawl, Reeves made his fortune as a cotton merchant. He recently gave up bodysurfing but still plays 150 rounds of golf a year. He’s 87, but he puts his functional age in the early 60s. “I’m not really paying attention to the chronological,” he says.

Reeves recalls meeting Brady while playing golf at Pebble Beach “maybe 20 years ago,” and the two have been close friends ever since. “I didn’t know much about him,” says Reeves, “but he was so gracious.” Through Reeves, Brady has met various other wise men, including Jimmy Dunne, 65, vice chairman and senior managing principal of Piper Sandler investment bank.

When Brady is in the company of these wise men, decades older, he spends a lot of time listening. “Learning from those people is really important to me,” says Brady. “I don’t think you can go through life and be fixed. I was listening to someone the other day, and they said, ‘The words I don’t know are the most powerful words because they’re limitless. It’s limitless potential.’ And as soon as you think you know something, you’re fixed.”

Reeves has given great thought to what makes Brady special and has come up with three bullet points:

• He makes people feel valued. “That could mean really listening—he’s an extraordinary listener—to someone he’s meeting for the first time.”

• He thrives on excellence, for himself and those around him. “He wants you to have what he has. He wants people to be the best they can—but he’ll help you get there.”

• He is a person of joy. “Pain is inevitable—certainly in football—but misery is optional, and Tom does not accept misery. Tom runs the opposite way. He runs to joy.”

Then Reeves absently adds a fourth. “Tom keeps his routines, but he is open to adventures.” And . . . wait . . . catch that? It sounds like a throwaway line, but aha. That, as much as anything, might unlock the secret to Brady’s—and, for that matter, our—longevity.

Yes, Tom keeps his routines, so much so that his fanatical habits figure prominently in the mythology. His sleep schedule and his infrared pajamas. His training and his plyometrics. We know about his hydration and his electrolyte intake. Lord knows we know about his diet and nutrition. He dares to eat a peach . . . and avocado ice cream. (There is a sports-media edict that says Brady cannot be discussed without a reference to avocado ice cream.) But he dares not ingest carbs, nightshades, dairy, white sugar or white flour.

Dylan Buell/Getty Images for The Match

Ross Andel, director of the School of Aging Studies at USF, notes that routines and good habits are essential for optimal aging. A Bucs fan, Andel sees Brady and his defiance of time and is unsurprised. “His ability to stay disciplined is second to none,” says Andel. “Other people look for a quick fix or go to extremes. He doesn’t mind hard work. He holds onto his schedule. There’s such a resilience.”

Yet when discussing keys to graceful aging, Andel also references an opposite, even contradictory, instinct: a willingness to adapt—“I never want to be fixed” . . . “he is open to adventures”—to stimulate new parts of the brain and pleasure centers. In short, to evolve.

Andel points to a German study in which volunteers were taught to juggle. As the subjects picked up a new skill, brain imaging revealed changes in gray matter. As the subjects became capable jugglers and the skill was no longer novel, the gray matter reverted to its levels before the study. “The brain had nothing to adapt to, so it put the neurons elsewhere,” says Andel. “It’s the stimulation, the change of environment that challenges the brain and redistributes our bodily resources.” That, says Andel, encapsulates Brady. “He’s unbelievably adaptable.”

So credit Brady for his rigidity. But his relentless success owes just as much to the opposite trait, his flexibility. Does he contradict himself? Very well then, he contradicts himself. He is large. He contains multitudes. Moving to a different franchise in a different state with a different corporate culture? That example of his adaptability is just one of many.

Brady might, rightly, be depicted as the exponent of clean living. But there he was in February, giving new zest to the phrase drunken fling as he hurled the Lombardi Trophy Frisbee-like from one boat to another during Tampa Bay’s Super Bowl celebration. He then put to rest any questions about his sobriety with the unforgettable tweet, “Noting to see her . . . just litTle avoCado tequila.”

Brady is an unapologetic capitalist. His NFL salary of $25 million is dwarfed by his various businesses and investments, from the TB12 health and wellness brand to his clothing line, to his 199 Productions content studio, to his stake and promotion of a cryptocurrency firm. His NFT company, Autograph, is widely considered an industry leader in digital collectibles. He’s arrowing toward billionaire status, if not there already. And he’s not simply slapping his name on products. He is poring over balance sheets and Zooming into board meetings, glimpsing his post-NFL life while still playing.

On the other hand, Brady doesn’t always show fidelity to the market. His NFL salary, which does not consign him to eating ramen, still ranks ninth in average annual value among QBs. “He’s never wanted to be the highest-paid quarterback,” says Arians, “because [doing so] would mean not getting maybe two other good players.”

As much as Brady values health, he mourns the rule changes that diminish the physical risk of football. “The game I played 20 years ago is very different from the game now, in the sense that it’s more of a skills competition than it is physical football,” he says. “It’s like being in the boxing ring and saying, ‘Don’t hit your opponent because you might hurt him.’ Look, we’re both able to protect ourselves. I’m looking at you. You’re looking at me. Let’s go.”

Brady made those remarks recently on Let’s Go, the podcast he hosts with former receiver Larry Fitzgerald and sportscaster Jim Gray each week. And this might represent the most striking example of Brady’s adaptability. For most of his career he was willfully, even strategically, unknowable. Not surly or standoffish, but you might say that long before COVID-19, Brady wore a mask. As he put it this summer on HBO’s The Shop: “What I say versus what I think are two totally different things. I would say 90% of what I say is probably not what I’m thinking.”

Whatever the case, lately we’re hearing from Brady more often than ever before. There he is on late-night couches. There he is in a self-effacing Subway commercial. And calling into Howard Stern. The podcast medium suits him especially well—not just his own, but others (“What did [I] major in? F------ football, man,” Brady said on actor Dax Shepard’s Armchair Expert). He’s also jacked up his activity on social media, often hilariously. After a tweet surfaced comparing the TB12 Method with Terry Bradshaw’s “TB 12 beers a day methods,” @TomBrady issued the A-plus retweet last month, “Tomato, tomahto.”

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

Brady accepts the premise that lately he has put himself out there. “I’m rediscovering my voice,” he says, “and I’m having fun with it.” The obvious correlation: Brady feels he is able to reveal himself and have this fun now that he is liberated from his coach in New England and from the tight organizational controls. He doesn’t deny that.

But there’s another correlation. His age. “I think there’s more comfort just as an older guy, too. My give-a-s--- levels are probably a lot less. I’m kind of like, O.K., what’s it gonna be like in 10 years? I’m really not going to give a s--- then.”

It is, of course, irresistible to hear Brady talk about his future and not indulge in speculation about how many more times the odometer can turn over. Licht has already stoked fires (and social media accounts) when he predicted Brady would play until age 50. He doubles down with SI: “I don’t see any signs of decline whatsoever.”

Brady predicts that the source of his decline—whenever that may be—will be spiritual, not physical: “Regressing would be a very difficult thing for me to see. As soon as I see myself regress, I’ll be like, I’m out. I don’t really want to see myself get bad. So it’s just a constant pursuit of trying not to be bad.”

Trying not to be bad? Really?

“I think if anything, the most challenging part is the emotional aspect of football for me,” Brady says. “When we lose, it’s depressing. When we win, it’s a relief. It’s not like the joy, the happiness—it’s a relief. Because when we win, sometimes just winning isn’t good enough for you, because you expect perfection, and when you expect perfection and it’s less than perfect, you feel like there’s a down part to that.”

Then again, this drive, this internal combustion engine, is what keeps Brady playing at this exalted level. Winning a seventh Super Bowl doesn’t dull his ambition for an eighth. Throwing a pass into a window the size of a playing card only increases his desire to deliver another one.

“It’s like hitting the perfect 7-iron,” he says. “You go, ‘How was that?’ And I go, ‘That was pretty great! I want to do it again!’ You just constantly keep chasing it.”

It was recently put to Brady: Is there anything specific he has yet to achieve in his unrivaled career? His first answer: not really. But he did note that, in all his years and for all that success, he has never won a game on a last-second Hail Mary.

The temptation is to tell Brady that he’s completed football’s ultimate Hail Mary. The backup at Michigan whose 40-yard dash time could be clocked with a sundial going from the sixth round to the GOAT pasture, with seven Super Bowl rings? Whose excellence remains unabated at 44? Except that a Hail Mary implies a level of luck. The Legend of Brady is predicated on anything but fluke or chance. It’s deliberate and smart and rational.

So here is a man—and a sportsperson—for all of time. And for this time. And as aging does its thing, as mitochondria begin to deteriorate, as the mortal coil unwinds, Tom Brady comes bearing lessons for us all about contorting and distorting time, if not stopping it altogether. Balance routine with new adventure. Even more than anatomy, it’s attitude and character that shape destiny. Head off into the sun, not the sunset.

And if we hydrate and eat right, so much the better.

Additional reporting by Greg Bishop and Jenny Vrentas. Additional research by Reid Foster.

• Billie Jean King Wins SI’s Muhammad Ali Legacy Award

• Zaila Avant-garde Wins SportsKid of the Year

• A Quarterback Evolution and a Coaching Revolution