Three months into the pandemic, 30 D-I sports teams have been discontinued, bringing far-reaching consequences. Can a broken model be fixed?

In August 2016, after Clayton Murphy became the first American man to win an Olympic medal in the 800-meter run since 1992, he was given a hero’s welcome at his school, Akron University.

There was a press conference at the football stadium, and plans were made for a commercial shoot and other promotional ideas. Akron’s athletic department couldn’t wait to use its star cross country and track athlete for marketing purposes. At the time, George Van Horne, senior associate athletics director for development & marketing, told the Akron Beacon-Journal that Murphy’s Olympic medal was worth “100 bowl games” in terms of exposure to the school. “That’s always been a part of our problem as a university, we don’t tell our story very well,” Van Horne told the newspaper. “We’ve got 25,000 of those stories on campus and we’ve got 146,000 alumni worldwide. He’s one of the fastest men in the world, let’s use him to tell that story.”

In May, less than four years after Murphy’s medal, Akron told a very different story: It eliminated the cross country program that helped make him a rising star in American running, along with men’s golf and women’s tennis. Since then, a highly motivated Murphy has joined other Akron alums in a fundraising effort that they hope will convince school leaders to salvage the cross-country program. “Universities across the board need to take a look at these Olympic sports and see the value they can have, and not be tossed aside,” Murphy told Sports Illustrated last week. “They threw away a major part of what made myself and others go to that university.”

As universities scramble to cover virus-related financial hardships, they’re sacrificing a piece of unique fabric in the American quilt: Olympic sports. In Division I alone, 30 athletic teams have been eliminated in eight weeks. Four schools have cut at least three sports and a fifth, Brown, discontinued a whopping eight athletic programs. According to one site tracking the cuts, more than 80 programs have been eliminated across all levels.

Thousands of advocates have rushed to the sides of coaches and athletes of discontinued sports, challenging school leaders, signing petitions and raising funds. They fear that the cuts are far from over.

“We are all holding our breath in the Olympic sports community,” says Kathy DeBoer, executive director of the American Volleyball Coaches Association. “The people in sports that are not dropped get to breathe again. It’s like there are six bullets in the gun and 10 of us are standing there. If you’re still standing, I guess you want to celebrate, but you don’t—you just start breathing again before the next round.”

DeBoer’s organization is one of 21 Olympic sports associations to unite under one umbrella, the Intercollegiate Coach Association Coalition (ICAC), with a mission to preserve broad-based college sports in the coronavirus era. The elimination of college sports, they say, hurts the feeder system for American Olympic teams, destroys the motivation of youth athletes and, despite assertions that these are money-saving decisions, actually can cost schools millions in tuition dollars.

They believe discontinuing teams is a quick and fruitless fix to a much deeper problem—an NCAA model that, because of riches in football and men’s basketball, has lost its original purpose of broad-based educational and athletic opportunities.

“It’s clear that the D-I model of intercollegiate athletics has been broken,” says Mike Moyer, executive director of the National Wrestling Coaches Association, “and COVID-19 is exposing it.”

***

At mid-major programs, deficits at athletic departments existed before the global pandemic struck. But the shutdown of campuses and economic downturn has dramatically worsened the situation, while giving cover to athletic directors already considering discontinuing sports.

Colleges around the country are bracing for significant losses in the coming fiscal year. Many programs are projecting at least a 20% reduction in revenue from various sources: cuts in state and federal funding; a decrease in institutional support; loss in ticket sales; and a drop in donations. The reductions extend to the university side. Even a giant like Ohio State is estimating a loss of $300 million in revenue, leading some to believe that a few D-I schools will do what several smaller universities have done—shut down completely. “We’re going to lose institutions,” Notre Dame athletic director Jack Swarbrick predicted last month.

The Football Bowl Subdivision level, which is the top 130 athletic programs in the nation, is itself divided into two tiers: the Power 5 (members of the Atlantic Coast, Big 12, Big Ten, Pac-12 and Southeastern conferences, plus Notre Dame) and the Group of Five (members of the American Athletic, Conference USA, Mid-American, Mountain West and Sun Belt conferences, plus independents). The sacrificing of Olympic sports thus far has fallen along that fault line: No Power 5 program has eliminated a sports team, at least not yet. Power 5 athletic departments can lean on cash reserves and the possibility still for significant TV money if the football season is played, but G5 athletic departments are strained by their reliance on school and state funding. On average, a G5 athletic program gets 62% of its revenue through institutional and state support. As enrollment dips and state economies decline, the gravy train stops rolling. Take, for instance, Central Michigan. In 2018, $30 million of CMU's $39 million budget came from those funds. Even before the pandemic struck, enrollment at the school had declined more than 10% from 2018.

In searching for places to cut, CMU eliminated men’s outdoor and indoor track. At some schools, a men’s track team can lose more than $1 million a year. In fact, the vast majority of Olympic sports teams, both Group of Five and Power 5, turn an annual loss in the six figures, if not seven. While Power 5 schools can balance that with upward of $20 million in profit in men’s basketball and football, things are different at the Group of Five level. Even football and men’s basketball often generate net losses. Connecticut, for example, lost more than $13 million in football alone in 2019, according to the Hartford Courant. However, those two sports draw tens of thousands to campus and are the catalyst for millions of booster donations.

Many administrators are following a systematic route to downsizing—salary reductions, staff furloughs and travel cuts—but when more is needed, “Olympic sports are being sacrificed,” said Western Michigan athletic director Kathy Beauregard. “There’s nothing worse you can ever have to do than cut sports.”

Some believe you should never have to discontinue an entire team. Olympic sports advocates contend that universities are in this position because of lavish spending on their two money-making ventures, football and men’s basketball. In an effort for Group of Five programs to keep up with their richer brothers, they are exceeding appropriate spending. Salaries are too high. Staffs are too large. Locker rooms are too extravagant. For instance, Cincinnati, which cut men’s soccer, pays football coach Luke Fickell $2.3 million a year. East Carolina, which cut four sports, pays football coach Mike Houston a salary of $1.4 million.

Meanwhile, Akron, eliminator of three Olympic sports, has dug itself a deep financial hole with something far worse than coaching salaries: coaching buyouts. The Zips’ 2018 coaching transition from Terry Bowden to Tom Arth cost them $1 million. In addition to that, Akron has an annual debt of $5 million for the construction of the $61 million InfoCision Stadium, at which it has yet to record a sellout since opening in 2009. Facilities debt service is an annual financial burden on nearly every school in FBS. According to the Knight Commission, teams had a total facilities debt of $722 million in 2018. That’s about $6 million per school.

“It is concerning. College sports is our secret weapon in the U.S.,” says Greg Earhart, executive director of the College Swimming and Diving Coaches Association of America. “Schools are still chasing a dream they can’t achieve. Every time an FIU beats Miami, it just gives them hope. These schools are getting outspent 3 to 1.”

DeBoer calls this an “existential crisis” that began a few years ago when the five largest conferences were granted autonomy powers. The gap has grown larger with the Power 5’s mega television deals and widened even more with the College Football Playoff. The CFP distributes $366 million to the Power 5 programs, including Notre Dame, while distributing $91 million to the Group of Five. According to 2018 figures, the richest Group of Five athletic program is UConn, ranking 52nd with a budget of $79.3M a year—and that program is losing $40 million a year and deliberating cutting sports this month. More than half of the Power 5 schools have a budget of at least $100 million.

“If you’re expected to compete with somebody with $50 million more than you, you’re under some incredible pressure,” DeBoer says. “The result is we’re trying to close a $50 million budget gap by cutting out our commitment to broad-based sports. Let’s say you save $5 million. Now you’re only behind $45 million. It just kicks the can down the road.”

***

Rob Kehoe has troubling stories from years of seeing the elimination of men’s soccer programs. In 2009, Maine's soccer coach was on the pitch for practice before receiving a message about an emergency meeting. He arrived at his office to learn that his program had been cut. A few years later, New Mexico slashed a soccer program that annually finished inside the top 25. “I thought,” says Kehoe, the director of college programs for United Soccer Coaches. “‘Who’s safe?’”

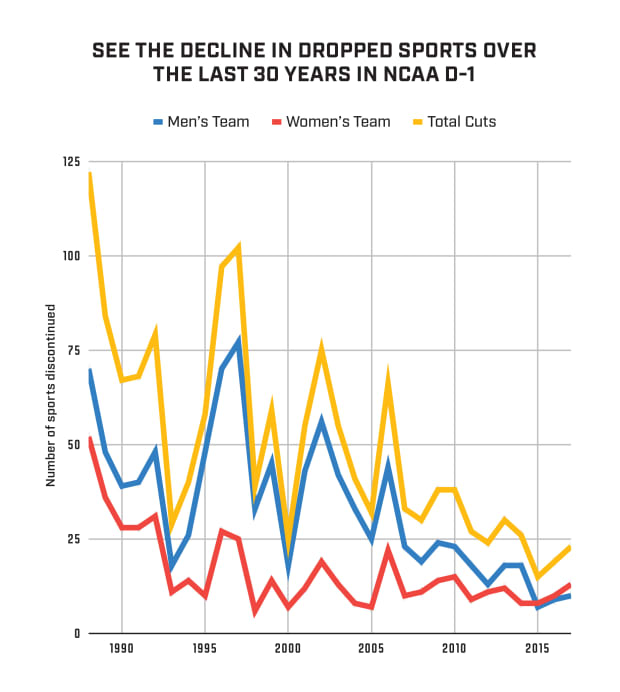

Eliminating nonrevenue sports is nothing new. For instance, UCLA, one of the great all-around athletic programs in America, cut men's swimming and men's gymnastics in the early 1990s despite having produced multiple Olympians in both sports. That said, there has been a steady decline in dropped sports since the very beginning of the Great Recession resulted in a single-year cut of 66 teams in 2006–07. In the last three years, 57 sports were cut, the lowest three-year total since the NCAA began collecting the data in 1981. The 30 sports eliminated so far this year marks a sharp reversal of that trend. Even if there are no more cuts in 2020, this would mark the highest single-year total in a decade.

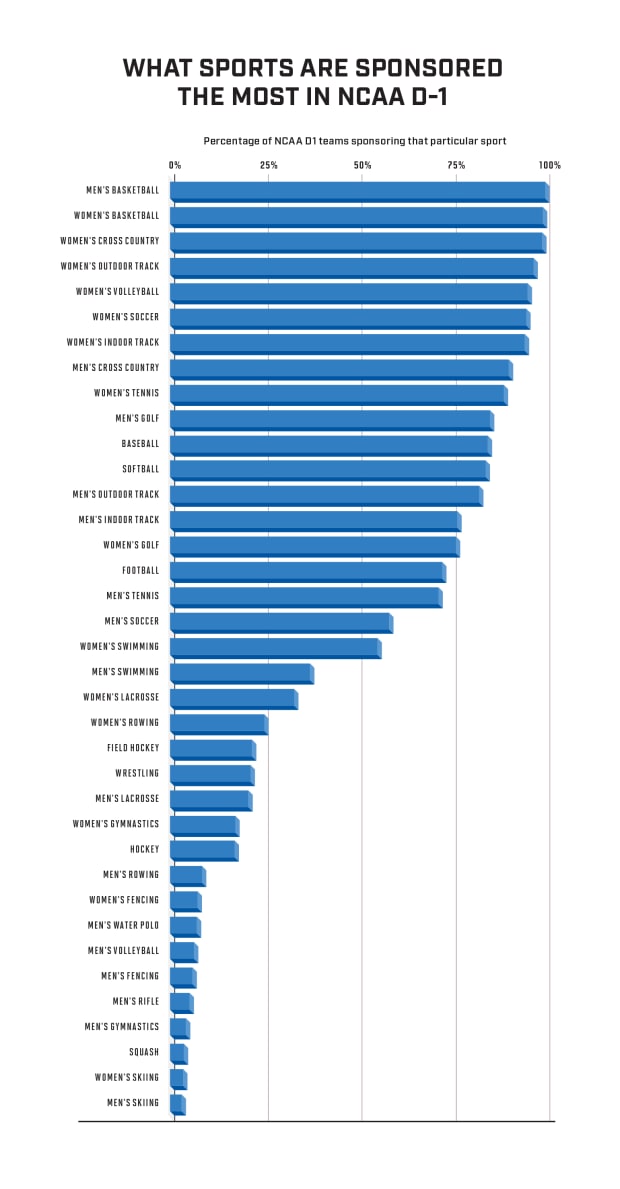

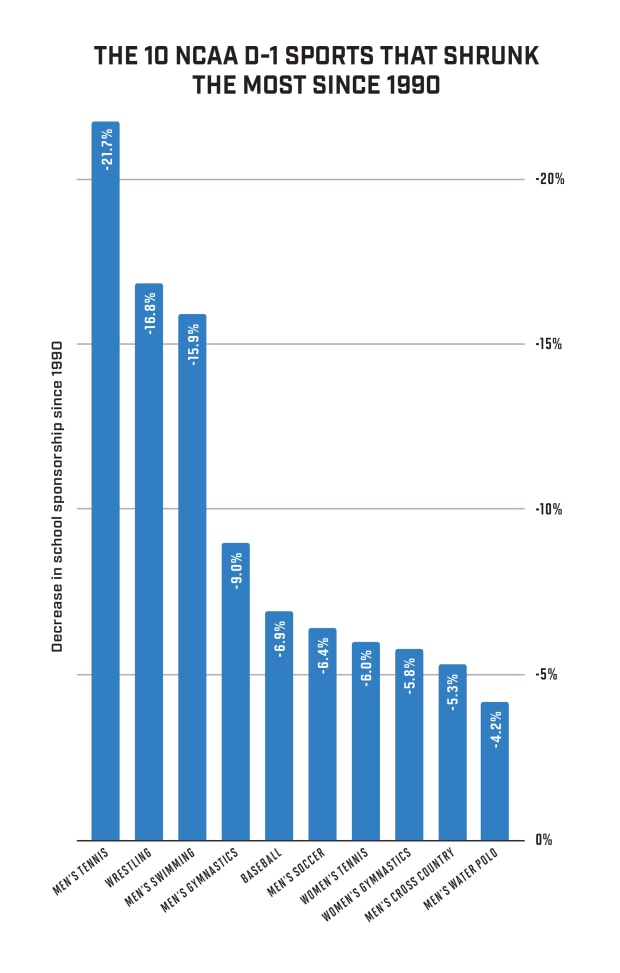

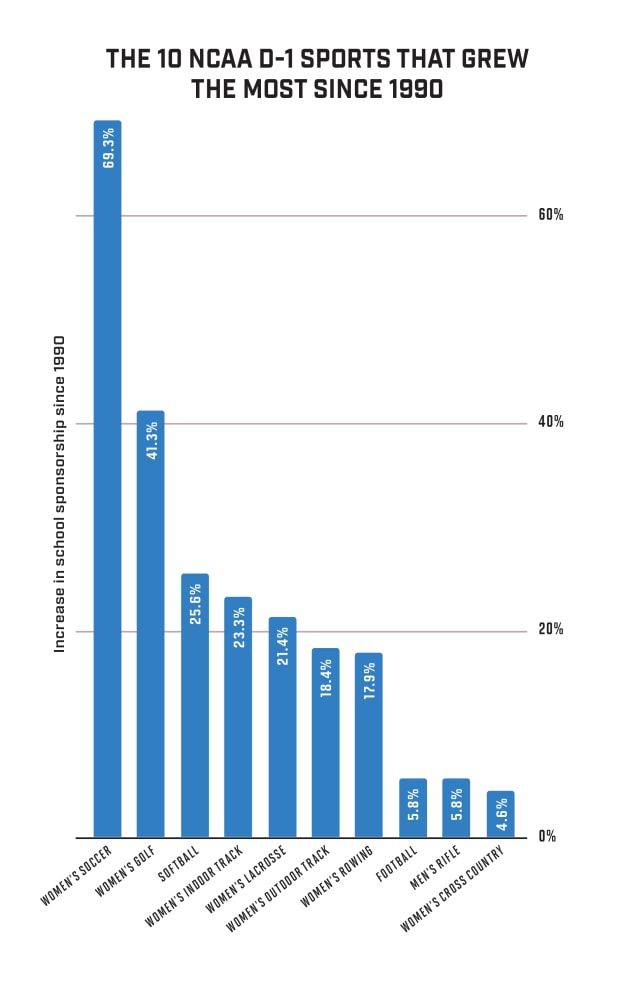

Over time, some sports have fared better than others. Since 1990, NCAA Division I membership has grown by 58 schools, yet at least eight sports—all men’s teams—are sponsored by fewer schools today than they were 30 years ago, including wrestling (37 fewer teams), swimming (25), gymnastics (24) and tennis (22). Proportionally, no sport has taken more of a hit than men’s tennis, which is sponsored today by 71.5% of the D-I membership. In 1990, 93.2% schools had men’s tennis.

It’s not getting any better. So far this spring, tennis has been the most popular choice to cut. Of the 30 teams eliminated, eight are either men’s or women’s tennis. Coincidentally or not, tennis is also responsible for having the largest foreign participation of any sport. About 60% of tennis rosters are not native to the U.S. “There’s somewhere around 7,000 scholarships available (in NCAA D-I), and there are just not enough American juniors to fill the scholarships,” says Tim Russell, the CEO of the Intercollegiate Tennis Association. “There have been some schools where the coach only recruits internationally, and there have been some ADs saying, ‘Can’t have a program of all international students.’” There are other reasons tennis is targeted, Russell says. The most common are costs associated with an indoor and outdoor facility.

There is another sport being targeted. In 1990, more than half of D-I membership sponsored men’s swimming. That number is now at 37%, trailing 19 other sports in sponsorships. In fact, women’s swimming, compared with other female sports, is also on the low end: Just over half of D-I schools have a women’s swim team.

Already this spring, two swimming and diving teams have been cut. To preempt the discontinuation of full squads, D-I swimming and diving coaches came together to voluntarily slash a combined $6.2 million from their 2020–21 budgets. Earhart, of the College Swimming and Diving Coaches Association of America, worries about a domino effect. Oooh, they cut swimming, so maybe we can, too. “I wonder about other schools in the AAC after East Carolina [cut],” he says. “People start to see this in the news. Parents have choices of what they want to enroll their kids in. Now we see fewer kids involved in swimming. If you don’t have 8-year-olds enrolling in swimming, you’re not developing the pipeline to get players to London or Tokyo [for the Olympics].”

Indeed, Sarah Wilhelmi, the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee's director of college partnerships says 88% of American summer Olympians in Rio had played their sport in college, and in the 2018 winter games, one-third of Americans were former college athletes.

Of the 30 D-I sports eliminated, 19 have been men’s teams. That is not just coincidence, college administrators say. Fearing Title IX violations, athletic directors can’t risk discontinuing too many women’s sports. Title IX requires schools to have a proportionate number of female athletes as it does female students, and it must grant female athletes the same athletic opportunities—scholarships, staffing, competitions—as it does male athletes. Football, and its 85 scholarships, can throw the numbers off kilter, forcing administrators to slash other men’s sports. Since 1990, the top seven sports experiencing the most growth are female, while the top six having the least growth were male.

“It’s been a trend,” says Andy Schwarz, an antitrust economist based in California. “The Department of Education says you’re not supposed to get Title IX compliance by cutting sports, but I don’t think there’s any punishment for schools that do that.”

New Mexico AD Eddie Nuñez says Title IX was a “driving force” in eliminating sports at his school. In 2018, UNM cut men’s soccer, men’s and women’s skiing and beach volleyball. Eight months of research preceded the cuts, which then triggered a backlash from alumni. “When you start down this road, it could resonate extremely negatively with your fan base,” he says. “It’s a tough narrative to manage.”

Most schools are violating Title IX anyway, says Nancy Hogshead-Makar, the founder of Champion Women, an advocacy group for girls and women in sports. In fact, East Carolina eliminated women’s tennis and women’s swimming to fall further below Title IX guidelines. The ECU undergraduate population is 57% female and its athletic department is a 50–50 split, says Schwarz. “I’ll be darned if I’m going to let COVID take more women’s sports,” says Hogshead-Makar, herself a former Olympic gold medal winner in swimming. “People say we shouldn’t be pushing Title IX right now because it’s a pandemic and there’s no money. My response is that when you go to fight to save women’s sports, it saves the guys, too.”

***

At Youngstown State, executive director of intercollegiate athletics Ron Strollo is cutting 12% from his budget, or roughly $2 million. More than 20 coaches will lose their jobs and several more will take pay cuts. But one move he won’t make is cutting sports.

In fact, the Penguins are adding them. Last year, Youngstown added men’s swimming and diving, and next year, women’s lacrosse will begin play. Each of his cross-country rosters will double in size. This is an “enrollment strategy” that will add 100 students to campus. “It's a little bit different than how some people are approaching this,” Strollo told Crain’sCleveland.com, a business blog.

A fact rarely acknowledged by athletic departments looking to make cuts: Olympic sports can generate millions for universities, filling what would be empty classroom seats with athletes who are paying full or partial tuition. The vast majority of small-sport athletes receive only partial scholarships, and many others pay their own way as walk-ons. Last year, in fact, Olympic sports athletes generated $3.6 billion in tuition to their universities, according to the Intercollegiate Coach Association Coalition.

For many Olympic sports teams, the NCAA designates scholarships to each team to parcel over a certain amount of roster sports. In men’s tennis, for instance, the number is 4.5 scholarships over a roster size of about 10. Roughly half of the roster is paying tuition. In swimming, women’s teams get 14 scholarships to use on rosters that can be as large as 40. Men get 9.9 scholarships over an average roster size of 28—a nearly 3-to-1 tuition-to-scholarship ratio. Men’s soccer and wrestling have 3-to-1 ratios, and women’s soccer is 2-to-1. Then there’s men’s volleyball, sponsored by just 23 D-I schools despite it having one of the widest scholarship-to-roster size ratios. “There are four scholarships and the average squad size is 20,” DeBoer says. “The math is clear.”

While trimming their own budget, athletic directors are often hurting their university’s bursar office. Sure, eliminating a men’s track team might save $1 million a year in the athletic budget, but what is it costing the academic side? A men’s track team is allowed 12.6 scholarships for an average of 39 athletes. According to a 2016 study from scholarshipstats.com, the average D-I male track athlete received $11,260 in annual athletic aid, the lowest of any men’s sport. D-I football players, who receive full scholarships, got an average aid of $36,070. A track team could be generating over $1 million to the university side. “But the accounting system in athletics doesn’t include that $1 million,” Schwarz explains. “That’s on somebody else’s books.”

There are ways, however, that the math doesn’t work. If a university is at capacity, a school could be costing itself by offering a discount (i.e. scholarship) to an athlete when a regular student would pay full price. But very few schools are at capacity, says Schwarz.

This spring marked the ninth consecutive year that general student enrollment has declined nationwide, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. Now is not the time to intentionally hurt enrollment, yet some athletic departments are doing it. Why? There is a disconnect between the academic and athletic sides, Schwarz says. Donna Lopiano, a longtime former college administrator now at the Drake Group, sees something else. “I’ve seen so many college presidents so shortsighted,” she says. “They're almost trying to prove that athletics are not above any department, instead of realizing how athletics is tied to enrollment and tuition numbers.”

Another downside: Olympic sports athletes are some of the most academically successful on campus. For instance, the Big 12 recently posted graduate scholarship recipients, and 17 of the 20 players are from nonrevenue teams. “As a former college wrestler, I have great concern for what this does to our presence on the (Olympic) podium,” said Big 12 commissioner Bob Bowlsby, a member of the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee's Collegiate Advisory Council. “I think it’s shortsighted to view the discontinuation of sports as a high-priority way of saving money.”

***

David Ridpath spent 15 months in Europe studying an alternative model of amateur athletics that he believes America should adopt: club teams. Across the globe, the most widely used athletic model is not tied to educational institutions, but is often government-backed clubs drawing participants from cities and regions of a country. Ridpath, an associate professor for sports management at Ohio University, even authored a book on the subject. “We are the only ones in the world to have this model,” he says, “and we’re seeing how fragile it is because of the overinflated focus on football and basketball.”

This is one idea, however unlikely, to fix what several believe is a broken NCAA model. There are others. Many Olympic sports coaches think a cap on coaching salaries and staff sizes would alleviate the issue, but that’s another far-fetched plan. Maybe some Group of Five schools could drop to the FCS level to lower costs and more adequately compete for a football championship, while their Olympic sports remain at D-I? Good luck convincing administrators on that move. The FBS moniker is a badge of honor for many programs, says Ridpath.

Is a split of the Power 5 and Group of Five into separate divisions possible? It’s a topic long discussed, and one that’s gaining traction given the virus’s impacts, but the hurdles would be significant. DeBoer, a leader of the volleyball coaches association, has another idea. Power 5 programs should use their TV contract and CFP riches to create new sports teams instead of enhancing existing ones. While Olympic sports have benefited from money earned through football—for example, volleyball head coaching salaries have increased by roughly $100,000 in the last five years—DeBoer would rather see the football monies used as seed cash for upstart sports programs. It’s another long shot, of course.

Maybe the solution is, one day, to reinstate programs lost during the pandemic. Thousands are fighting for that to happen sooner rather than later. Two sports have been successfully reinstated through grassroots efforts. At Bowling Green, baseball alumni raised $1.5 million in two weeks for a sport that costs $750,000 a year to operate. At Alabama-Huntsville, a similar fundraising effort raised $900,000 to save ice hockey.

But for every success, there’s five that have stalled. A group in South Carolina dubbed "Save Furman Baseball" has been informed by the university that the school will not consider any fundraising. Old Dominion officials rebuffed attempts from Moyer’s wrestling association to revive the group with fundraising.

At Akron, the fight continues. A campaign led by Murphy and another ex-Akron cross country runner, Jordan Olson, raised $80,000, an amount that would fund the Zips’ cross-country program for roughly a decade. The school declined the offer, says Olson, a 30-year-old who coaches high school girls track and cross country in Medina, Ohio. Cross country is one of the cheapest to operate because it is a shared sport. Coaches, athletes and even scholarships are under the umbrella of the track program. Long-distance track runners participate in cross country in the offseason, the fall. By Olson’s calculations, Akron cross-country costs just $7,900 annually in expenses, most of that for travel and gear.

Only six Division I schools have track but don’t sponsor cross-country, Olson says. This is so rare for a reason. Cross-country is used by track coaches as a recruiting tool to land long-distance runners. Because of the number of walk-ons and others on partial scholarships, Schwarz and Olson have estimated that Akron is losing roughly $200,000 a year in tuition payments by slashing the sport. “Here's our main argument: In four years, you won’t have distance runners on Akron’s track team,” says Olson. “Runners want to run cross country and then do distance in track. No one just says, ‘I want to run distance in track!’”

Olson still has faint hope. Through word of mouth, some Akron Board of Trustees members have shown interest. He’s hoping to at some point get an audience with them and the school president. Meanwhile, Murphy, the former bronze medal winner, wrote letters to both the president and athletic director requesting a meeting with them both. The president’s office responded by sending him a canned statement they released to the public. He did talk to Akron athletic director Larry Williams, describing the conversation as unproductive.

Murphy is in the process of moving from the West Coast back to Ohio. One of the first things he plans to do when arriving back in the Midwest? Knock on some doors for answers. “I have not received one reason that’s been compelling or made sense,” he says. “I’m extremely frustrated that there has not been an open, honest conversation. When I get there, I’m going to reach back out to them.”