In Azerbaijan, where an authoritarian president menaces the media, an outspoken reporter was physically attacked because of his Facebook post about soccer. Did he die for what he wrote? Or for what he represented?

The exchange could have occurred anywhere on our sports-addled globe,

on any day of our games-filled calendar. It fit a familiar pattern: Star athlete does something controversial. Journalist criticizes said athlete, maybe on social media. Athlete becomes angry with said journalist. Sometimes athlete and journalist talk it out, and usually the dance ends there. But what if this happened in a country where the ruling party paints journalists who challenge authority as enemies of the people? And what if that country has a culture of impunity around attacks on journalists? What then?

On June 12, Wales and Switzerland met in Baku, Azerbaijan, in the second game of the pandemic-delayed Euro 2020, and throughout the soccer tournament three more matches, including a quarterfinal, will take place in the gleaming Olympic Stadium of the Caucasus capital on the Caspian Sea. The former Soviet republic has made the hosting of major sports and pop culture events a cornerstone of its global p.r. campaign, in recent years welcoming an annual Formula 1 race, a Europa League soccer final (in ’19), the European Games (’15), even the wildly popular Eurovision Song Contest (’12). And for good reason. Azerbaijan needs to salvage its reputation.

Last September the country entered a 44-day war with neighboring Armenia over disputed territory in Nagorno-Karabakh, which left more than 5,000 people dead. Strongman president Ilham Aliyev (whose father ruled before him, dating to the Soviet days) has been accused of human rights violations by a variety of European courts, including the use of torture, in his crackdown on independent media and nongovernmental organizations. And in April, Reporters Without Borders ranked Azerbaijan 167th out of 180 countries in its annual press freedom index. “Aliyev has been waging a relentless war against his remaining critics,” the nonprofit organization wrote. “Independent journalists and bloggers are jailed on absurd grounds if they do not first yield to harassment, blackmail or bribes. In a bid to silence journalists who continue to resist in exile, the authorities harass their family members.”

Against this backdrop, on Aug. 6, 2015, the Azerbaijani soccer club Gabala had one of its greatest on-field triumphs. Led by captain Javid Huseynov’s two goals over two legs, Gabala defeated Apollon Limassol of Cyprus to advance to the final qualifying stage of the Europa League, the continent’s second-most prestigious club tournament. During the celebrations on the field in Baku, Huseynov—a fixture, too, on Azerbaijan’s national team—raised the flag of another nation, Turkey, toward the fans of the Cypriot team in what was clearly a politically charged gesture. (Turkey, Azerbaijan’s ally, invaded Cyprus in 1974 and still occupies territory on the northern part of the Mediterranean island nation, though Turkey’s sovereign authority remains unrecognized by the international community. Apollon Limassol, the vanquished soccer foe, represents the rival Greek influence on Cyprus, featuring Greece’s blue-and-white colors and its eponymous god of mythology.)

Afterward, in the stadium’s halls, video captured an exchange: A Cypriot journalist asked Huseynov why he’d raised the Turkish flag; Huseynov, in response, banged his fists together twice and walked away.

A gesture is a complex thing. On the television series Friends, for example, the same banged fists were jokingly interchangeable with the middle finger. But some observers expressed concern over Huseynov’s response. The next day, on Facebook, an independent Azerbaijani journalist named Rasim Aliyev shared a news story headlined FOOTBALLER JAVID HUSEYNOV'S OBSCENE GESTURE TO CYPRIOT JOURNALIST and wrote, “I do not want such an immoral, ill-bred and unmannerly player to represent me in Europe.”

By then, Aliyev (no relation to his country’s president) had been taking a moral stand for years, working as a journalist with the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (IRFS), a Baku-based nonprofit where one coworker describes him as “an honest, principled person defending his and others’ rights and the freedom of speech.” Bearded and beetle-browed, Aliyev acted as a trial monitor, a media-content monitoring expert, an editor and a reporter, investigating attacks on other journalists. He frequently defied state orders against filming police violence toward protesters at opposition rallies. In 2013, after an officer at a protest punched Aliyev (who was wearing his press vest), a photograph of the incident went viral across Europe. The following year, he was named chair of the IRFS, effectively making him the head of Azerbaijan’s effort to protect journalists. In ’15 he was preparing to marry his fiancé, Guler Abbasova, when he wrote his Facebook post about the soccer gesture.

The reaction was swift. Elshan Ismayilov, a cousin of Huseynov’s and a former under-19 national team player himself, posted an angry reply on Facebook. Then came two phone calls around noon: The first was anonymous (later revealed to be Ismayilov) and profanity-filled; the second, three minutes later, was from Huseynov. The Gabala midfielder demanded a retraction, arguing that his fist-bashing gesture had been misinterpreted.

Aliyev typed out a new Facebook post: “I had a conversation with Javid Huseynov, and according to what he told me, these hand gestures were not offensive at all, but were meant as a sign of friendship between Azerbaijan and Turkey. I advise Javid to make a statement to the media about this video, which has been misunderstood.”

At 3 p.m., Ismayilov rang again, this time identifying himself. He said he’d spoken to his cousin; now he wanted to meet Aliyev at a teahouse for a friendly chat. Aliyev said that wasn’t necessary, that the situation had been resolved, but Ismayilov insisted, and so they agreed to meet at the Bayil Market, just off the waterfront in Baku.

A CCTV camera would capture, beyond dispute, what happened next. At 4:20 p.m., Aliyev arrived in front of the market. He got out of his car and shook hands with Ismayilov and a friend of his—whereupon Ismayilov wheeled around and kicked Aliyev square in the chest with the full force of a pro soccer player. The journalist crumpled to the pavement as his attacker and several other men, entering from the periphery, continued to kick him until he escaped, staggering across the street to safety.

Aliyev arrived by ambulance at Baku’s City Clinical Hospital No. 1 at 5:15 p.m. and told his examining doctor that, beyond his four broken ribs, he couldn’t hear out of his left ear, where he’d been struck. The medical staff administered painkillers, but Aliyev’s injuries, they said, didn’t seem critical. That would be the opinion, too, of a string of well-wishers who visited over the next several hours: Aliyev’s mother, Teyfura; two IRFS colleagues; and Huseynov, the soccer star, who arrived with his club manager and said he would make things right (but who then left quickly when police arrived to take Aliyev’s statement). Abbasova says she wanted to visit, too, but her fiancé told her, “I’m fine—I’ll leave the hospital and go home tomorrow.”

In his hospital bed, Aliyev felt strong enough to give an interview to Meydan TV, another news agency in the crosshairs of the government, describing the events right up until he “extended my hand to greet [Ismayilov]. When we shook hands, I received a heavy blow.”

Despite his pain, Aliyev was in “more or less a cheerful mood,” recalls one of the visiting IRFS colleagues, Mehman Huseynov (no relation to Javid), who left the recovery room around midnight. An hour later, though, Teyfura Aliyeva received a call from the hospital. Her son’s condition had deteriorated, a nurse told her, due to internal injuries, and doctors were planning to operate. She rushed back, arrived at the intensive-care ward at 1:30 and couldn’t believe what she saw.

Aliyev’s mouth and eyes were wide open, his body lifeless. The head of Azerbaijan’s organization to protect journalists was dead at 30 years old.

Rasim Aliyev's death generated eye-catching global headlines, as well as demands from the European Union, UNESCO, Amnesty International and a host of other international organizations for a full and transparent government investigation. President Ilham Aliyev, facing pressure over the fourth suspicious death of a journalist during his now 18-year rule, announced that he was “seriously concerned” and that he would personally oversee the case. None of which provided any relief for Emin Huseynov, Mehman’s older brother, who founded the IRFS and worked closely with Rasim until 2014. “When famous journalists are arrested, it’s only the president who decides should we arrest them or not,” Emin says. “It’s nobody else.”

Within two days of Aliyev’s death, police had made six arrests. Ismayilov and the four men with him during Rasim’s beating at Bayil Market were charged with causing grave harm to a person resulting in death; and Javid Huseynov, who had just enjoyed his greatest moment on the field, was charged for his failure to alert police about a crime that they said he knew his cousin was planning. The Baku City Prosecutor’s Office completed its investigation quickly, and trials were set to begin in January 2016.

But those were the only arrests, the only charges. The people closest to Aliyev believe that vital questions—questions about responsibility and accountability—remain unanswered.

Emin Huseynov sighs. He misses his family in Azerbaijan, but he knows he can’t go back. He misses Rasim Aliyev, but he knows his friend won’t return. Huseynov is in exile now, stripped of his Azerbaijani citizenship and living in Watertown, N.Y., 30 minutes south of the Canadian border, with his American wife, Sarah, and their daughter. With his thick, dark hair, piercing eyes and five-o’clock shadow, Huseynov evokes Al Pacino, circa Carlito’s Way. Having recently moved from Switzerland, he’s still getting used to big-box stores and the eight-hour time difference from home. Seven years have passed since Aliyev helped save him from arrest and imprisonment, and Emin believes his friend paid the ultimate price for that bravery.

A lawyer and economist by training, Huseynov created the IRFS in 2006 as a journalism and free speech advocacy group. Aliyev joined on a year later and soon became a board member. “He always liked to be on the front line,” Huseynov says.

The same can be said about Emin, although this approach has come with risks. In 2008, he suffered brain injuries from a police beating. (His case against the Azerbaijani government was ruled in his favor by the European Court of Human Rights.) Two years later the country’s ruling party gained full control of the legislature and passed new amendments opening the pathway for authorities to launch tax inspections on unregistered NGOs that receive foreign grants. In ’14 the state cracked down on the IRFS, raiding its offices, cutting off its bank accounts and trying to chase down its founder.

Aliyev became the getaway driver. He ferried Huseynov to a safe house outside Baku and picked up a $5,000 wire transfer in the western city of Ganja to help support the escape effort. “They tried to find me,” says Huseynov. “They put my photo in all the bus stations and public transport, like a wanted guy.”

Over 10 days in the safe house, Huseynov changed his appearance, dyeing his hair and growing a beard. In a scene out of a spy movie, another friend helped deliver him to the Swiss Embassy in Baku, where he stayed for 10 months.

While Huseynov was in limbo, Aliyev took his place as the chairman of the IRFS. He kept the operation going during its most difficult moments, shuttling between Azerbaijan and neighboring Georgia, where the outfit established new bank accounts. Finally, in June 2015, Huseynov escaped his home country, flying out with a Swiss government delegation that had attended the opening ceremony of the European Games. Fewer than two months later, Aliyev was dead. And Huseynov is convinced that those two events are connected.

On July 25, 2015, two weeks before the postgame incident with the Azerbaijani soccer star, after Aliyev published photographs of Baku protesters demanding the resignation of the president, Huseynov’s friend reported receiving a threat on social media: “You will be punished.” He filed a complaint that day with police, who took his statement, but as far as the Huseynov brothers can tell, no measures were taken to address the menacing message.

Huseynov sighs again. “I told him, ‘Rasim, I have a bad feeling. The government has some kind of evil mentality to try to use this vendetta against you. You should leave Azerbaijan.’ ”

The IRFS founder is clear in his belief: He doesn’t think the altercation with the soccer player was the end of Aliyev’s story. Three years after the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi by Saudi Arabian government operatives drew attention to how authoritarian regimes repress critical media, Huseynov believes the Azerbaijani government snuffed out his friend with the aid of the hospital staff. (In an email to Sports Illustrated, an Azerbaijani state official denied the allegation, calling it a conspiracy theory.)

“Sometimes they don’t do anything. They just let you die,” Huseynov says, “and they say, ‘Look, this is an accident that’s happened. Sorry. We can’t help them.’ That’s how things work in my country. . . . I was speaking with Rasim one hour before his death [by phone], and my brother had been with him in his room. The doctors said: ‘He looks very good. In the morning we’ll probably send him back home.’ ”

Halfway across the world, Emin Huseynov’s younger brother, Mehman, logs onto a Zoom call from a trusted café in Baku. Only in the last year has he shaken the feeling that his apartment is under state surveillance, and he still feels most comfortable in familiar places and around people he knows well. Trust is a tough thing to find when you believe you’ve been jailed unjustly by your government.

In 2008, Mehman was just 19, the whiz-kid sibling of the IRFS chair, when he met Aliyev, who he says at first appeared like “just another city street guy. But over time he proved to be a completely different person, a deep thinker and open-minded. He was very brave, as if he didn’t have any feeling of fear. He was in his element when he was covering the wrongdoings of police, confrontation between civilians and authorities.”

After college Mehman joined the IRFS as an anti-corruption blogger, often working with Aliyev—he took the photo of Rasim being punched by a police officer—and his years since have been filled with bravery. But also turmoil. A few months after Emin escaped Azerbaijan, Mehman was the last known person, outside of medical staff, to see Aliyev alive in the hospital. Two years later, after filling Rasim’s role atop the IRFS, Mehman, too, drew the government’s wrath: He was jailed for two years for allegedly defaming a police officer, who he said had tortured him. While in prison, in 2018, he began a hunger strike in response to new charges that would have extended his confinement by seven years. Finally, in March ’19, after some 20,000 protesters marched in Baku in his support, and after the Council of Europe called for his release, he was set free.

Now 31, Mehman is one of his country’s few full-time investigative journalists, and he has 215,000 followers on YouTube and Facebook combined. “We are a small but flexible team,” he says of Sancaq, the sociopolitical magazine he edits, “and our primary purpose is to [expose] the properties [and associated businesses] of public officials who are involved in corruption cases.”

His is a tricky business, though—especially in Azerbaijan, and especially with the history of the Huseynov brothers, Rasim Aliyev and the IRFS tied to him. “When I post something to social media, I have to check every single word to be sure I did not cross the red line,” he says. “We, the independent journalists, have to define those red lines and be careful not to cross them. Otherwise, you understand very well the crackdown that might follow.”

Where are the red lines in his pursuit of justice for Aliyev? Mehman isn’t quite sure. Wherever they are, though, he isn’t afraid to push right up against them. “What the authorities wanted was to identify the so-called scapegoats [the men who beat Aliyev] in order to present to the public that some people got punished for what they did,” he says. “We understand very well that Rasim’s death was orchestrated by the government, as a revenge for his assistance to take Emin to a safe location.”

In Baku, the 2016 trials relating to Aliyev’s death—one for Javid Huseynov, and another for Elshan Ismayilov and four associates, both in the Court of Grave Crimes—drew international media coverage. The proceedings against the group of five started first, and in a surreal twist both the lawyers representing the victim and the alleged attackers asked the court the same question: Why was the hospital’s medical staff not being prosecuted for negligence?

Three months earlier, Azerbaijan’s minister of public health, Ogtay Shiraliyev, had written to Baku’s city prosecutor, clearing the doctors at Hospital No. 1, which he oversaw, of any fault in Aliyev’s death; medical staff, he said, had given Rasim the proper examinations and treatments. And when Aliyev died, the official cause—essentially, heart failure spurred by the blows to his body—was produced by two separate state-supported sources: one expert who autopsied the body but had no access to the hospital’s examination notes, and a second expert who had access to Rasim’s medical notes but didn’t perform an autopsy.

But as both the defense and Aliyev’s family noted, doubt was cast on any official state story when the court refused to admit into evidence Aliyev’s initial X-ray image, as well as any CCTV video, which would have captured anyone who’d entered his hospital room. (The clinic had failed, too, to perform a CT scan for Rasim’s head, thorax and abdomen, which likely would have detected any organ injury, and, in the event of internal bleeding, prompted his immediate delivery to the operating room.)

Ultimately, the court refused a petition to indict Aliyev’s doctors, which led relatives of the accused attackers to throw chairs and shout at the judge, triggering the deployment of tear gas in the courtroom. Teyfura Aliyeva, too, was incensed over the judge’s decision, but she still demanded accountability for her son’s assailants. “I want these people to be given the most severe punishment provided by law,” she said in court. “Because they all knew where and why they were going.”

Finally, on April 1, 2016, after 18 hearings across three months, the verdicts for Ismayilov and his four coconspirators were announced: guilty, with Ismayilov receiving 13 years in prison while the others got slightly shorter sentences. Javid Huseynov’s ruling arrived two months later, after 12 hearings largely focused on whether he was aware of his cousin’s plans to attack Aliyev. (Huseynov maintained that he had not known his cousin’s violent intentions and that he called him off, which contradicted Aliyev’s videotaped telling, in his hospital bed, where he recounted Ismayilov’s saying that Huseynov had sent him.) In the end, Huseynov, too, was found guilty. The man who had captained his club so far into the Europa League, who had played more than 50 times for the national team, was sentenced to four years in prison.

Almost immediately there were appeals. Aliyev’s father, Mammadali, announced that the family had lodged a formal complaint, hoping to launch legal proceedings against the clinicians. (“The doctors have played as much a role in Rasim’s death,” his wife said in court. “We want the doctors to be brought to criminal responsibility as well.”) The lawyer for four of the defendants posited, too, that Aliyev’s fatal injuries had been inflicted on him in the hospital. “They tore his spleen and pancreas after he died,” said Shamsaddin Guliyev, who had no smoking-gun evidence for his claim but plenty of reason to distrust the state-run institution. “If his injuries were serious and he had a torn spleen, as stated in the medical report, why did they not operate on him as soon as he came to the hospital, but waited for eight hours?”

Ultimately, one plea for reconsideration was granted. That October, fewer than five months after Javid Huseynov was convicted, the Baku Appeals Court reduced his sentence to one year and two months, and he was released for time served. Huseynov didn’t respond to an interview request for this story, but he spoke in 2018 to the publication Xalq Xeber (People’s News) about his experience. “I was just at the top of my career, and I had completely different dreams,” he said of being arrested five days after reaching his sporting pinnacle. “I do not know how such an event happened to me. Maybe it was a test, maybe it was my destiny. But what burned me was that in my best days I was hit not by myself but by others. And I was the one who suffered the most in this case. . . . In the blink of an eye, I lost everything.”

Mehman Huseynov doesn’t want to hear it. “I would say that impudence and obscenity are the qualities that would characterize [Javid],” he says. “After he got released, he actually continued his soccer career.”

Indeed, Javid Huseynov, now 33, still represents Gabala, and he came back to play for his national team between 2017 and ’19. Today, on Huseynov’s profile page on the popular reference site Transfermarkt.com, his 14 months away from soccer are referred to as a “career break.”

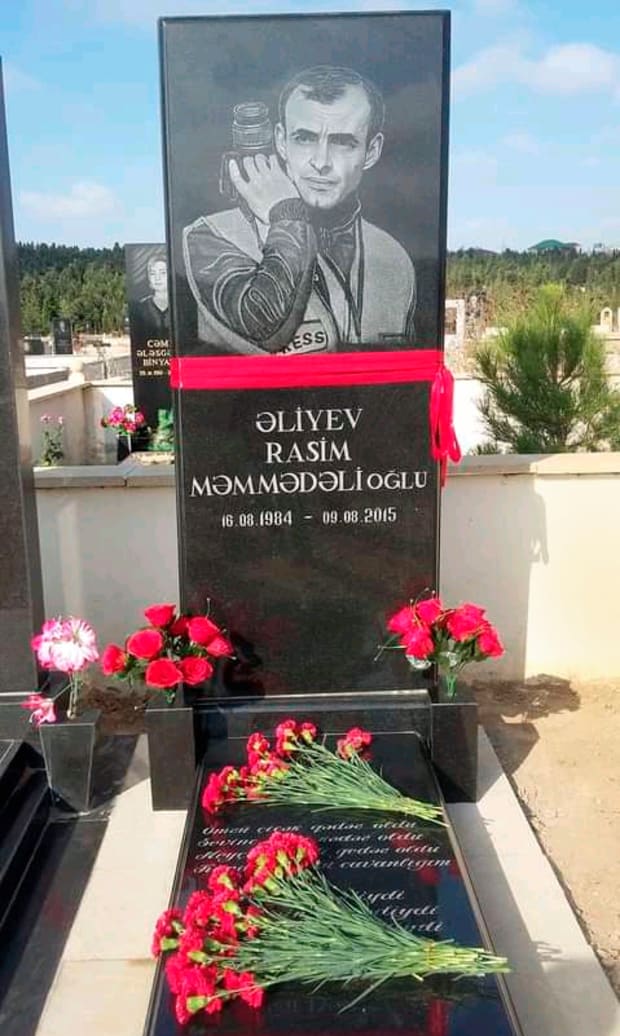

Rasim Aliyev’s gravestone lies next to the markers for his late grandparents in Mehdiabad, a settlement of 6,000 on the outskirts of Baku. The polished slab of black granite bears the etched likeness of the young journalist in his element, holding a camera and wearing a vest with PRESS emblazoned across the chest. Guler Abbasova has paid her respects here many times in the six years since her fiancé died, but she politely declines to revisit his death. “It hurts me” to discuss, she says. Teyfura Aliyeva, too, turns down an interview, fearing for the safety of her daughter, Gulnara, a schoolteacher.

As busy as Mehman Huseynov is with his investigative reporting, he stays in touch with his old friend’s family, he says, “because his family is also my family.” He isn't watching the Euro 2020 soccer games in Baku, and not just because he’s hardly a sports fan.

“The ultimate end [of hosting Euro matches] is to promote the image of the ruling family as if they were open-minded, pro-European, very modern people,” he says. “But why wouldn’t they spend their money on solving domestic issues? We have serious problems with unemployment. We just finished the war, and the veterans are struggling. Instead they just present themselves as a passionate government promoting sports.”

Why hasn’t Mehman left Azerbaijan and joined his brother in upstate–New York exile? After all, he’s had plenty of opportunities. The evening is growing late in his Baku café, but before signing off his Zoom call Mehman wants to explain why he continues to challenge that red line, why he still presses his luck by investigating the leaders of an authoritarian government.

“I decided I wouldn’t leave because I was born here. I grew up in this country. My mom’s grave is here,” he says. “I was subjected to torture many times. But now we are seeing at least slight changes for the better. If traffic police in this country are afraid of demanding a bribe, this means our activism has started to yield some results. If some officials are changing the public-service system for the better, it actually means that we—the journalists, bloggers and youth activists—are doing something. Why should we leave? We should rather stay here. And I would say that I am sure we will survive until the day when we see in Azerbaijan the country we are dreaming of.”

Mehman wonders something else, too. What if, in staging parts of Euro 2020 in Baku, the world takes notice of what’s happening in his small corner of a former Soviet outpost? What if telling Rasim Aliyev’s story not only honors a fallen friend but also drives action for real change? What if, at long last, some form of justice comes to Azerbaijan? What then?

• 'This Should Be the Biggest Scandal In Sports'

• Portugal is Prepared For Its Post-Ronaldo Period

• What Top-Ranked Belgium Has Left To Prove At the Euros