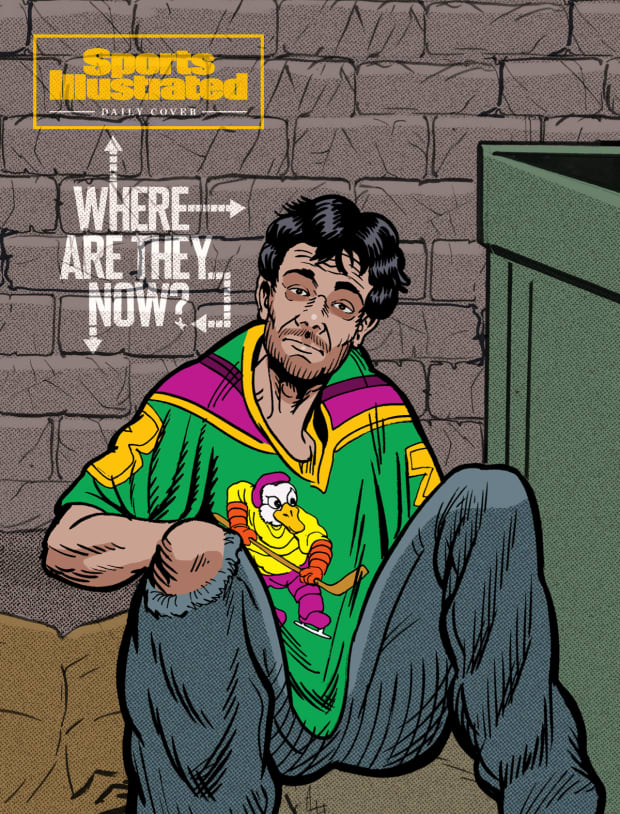

As a teen Shaun Weiss filmed his scenes as Goldberg the goalie at the L.A. Kings’ arena. In his 30s he slept on the ground outside.

Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. Come back all week for more WHERE ARE THEY NOW? stories.

On a cool February afternoon in the Valley, Shaun Weiss pulls his gray 2011 Nissan Altima into the parking lot of a shopping center and limps into Brent’s Deli. He injured his hip about eight months ago falling out of bed, and he’s still figuring out how to get it fixed.

For now, he orders a pastrami sandwich with a diet cola and pulls the black Wayfarer shades from his eyes. Slacks and a blue button-down shirt hang loose from his thin frame. A fresh haircut is stylishly messy, salt-and-pepper; same for his goatee, which is neatly trimmed.

Weiss, at 43, has been sober for two years now—long enough that he feels comfortable joking about it. “That’s the great thing about drugs,” he says. “It’s this profound accomplishment to simply not do something.”

Illustration By Felipe Flores

The food arrives, and Weiss digs in, using his tongue and lips to mash it all up just so. “I have to do all these little maneuvers,” he says.

That’s because his top teeth are all gone. Until a few months ago, his bottom teeth were, too.

“People think it was the meth,” he says. “But also: I got my teeth kicked in.”

Shaun Weiss was 5, growing up in New Jersey, when his mother, Rajpattie, took him to a casting call in Manhattan. Soon he had a talent agent, a series of Jell-O commercials and then gig after gig, culminating in the 1992 family hockey movie The Mighty Ducks. As Greg Goldberg, Weiss stole his scenes with charisma and comedic timing uncommon for his age. He was the goalie afraid of pain, so terrified of a puck that he’d dive to avoid a shot, even in full gear. In one scene, his defining moment, teammates tie him to a net and pepper him with shots until he realizes, “Hey, this doesn’t hurt!”

“That’s a lot of horses---,” Weiss says 30 years later. That scene “hurt like hell. There are areas that are not protected … like this area of the crotch, not quite protected by the jockstrap.”

In a flash, he was a full-fledged child actor. He starred in two Mighty Ducks sequels and director Judd Apatow’s first film, Heavyweights, alongside a young Ben Stiller, and he popped up all over TV: on Boy Meets World and Saved by the Bell and The King of Queens and Freaks and Geeks.

At one point, without any discussion, Weiss says his mother sold all of his things and relocated him and his father, Charles, to L.A., but Shaun doesn’t complain about this—or about the way he was raised, except to mention that Rajpattie could have done better to curb his terrible eating habits. (Did she want me to stay overweight to land more roles? he wonders.) Generally, he describes his parents in warm, kind terms. He says he loved show business. “I never felt pushed into it.”

Weiss’s older half-sister, Loretta, who’s 18 years his senior, sees it differently. She paints Shaun as a sweet soul who never wants anyone else to feel bad—but “all the problems he faced later,” she says, “you can probably trace back to our mother.” As Shaun’s career took off, Rajpattie took over as his business manager and regularly disappeared to Las Vegas with his money. When Shaun was 13 he went to buy flowers for a girlfriend and had his credit card declined, things had gotten so bad. (He says today that he doesn’t know how much money he made from his early acting jobs, but he considered that income to be his mother’s as much as his, since she’d helped him earn it.)

Shaun was broke, outside of the occasional residual check, which would prove challenging for someone who, Loretta says, “wasn’t prepared for life—[who] was never taught proper coping skills.” Weiss admits: “I thought I knew everything about everything. … And I was spoiled.” He remembers “driving around in a gorgeous BMW M3, and I was like, ‘This should be a Corvette.’ ”

When Rajpattie died of a heart attack, in 2008, Weiss says he started to drink excessively. “I became unglued.”

For the greater part of the next decade, Weiss cared for his diabetic father more or less on his own, while trying to navigate life as an aging child star, cobbling together guest TV spots, writing and production assistant gigs, and other odd jobs in the industry, “kind of holding things together with spit and duct tape,” he says. Old acting friends found their way into new, more mature roles, but Weiss struggled to land work, and he burned through his meaningful Hollywood relationships as his alcohol use worsened. Around this time, he says he also started to use various recreational painkillers.

Illustration By Felipe Flores

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

Weiss circles one friendship in particular, the dissolution of which captures his decline. He says that Apatow helped him check into and pay for a rehab facility, and that he assisted in finding employment: Apatow paid Shaun to write and do production assistant work on movies and, on one occasion, to write an awards speech; and Apatow helped him secure a gig writing jokes for the 2011 Oscars. At one point, Weiss says Apatow even gave him the laptop the director had used to write The 40-Year-Old Virgin. “I cherished that thing,” Weiss says. “It was like if your favorite baseball player gave you their glove.”

But work wasn’t steady, and when Weiss did find it, he says he felt underpaid. With frustrations mounting—he faced eviction from his apartment and put his father in assisted living—Weiss finally exploded on his friend.

Around Christmas 2012, he called Apatow and started yelling. “I was watching everyone around me [succeed], and I was essentially bringing people coffee, and I got angry about that,” Weiss says. “If you look at the cast picture of Freaks and Geeks”—a show on which Weiss was a relatively minor character—“I’m the only one that’s not a f------ millionaire 10 times over [now].” (Apatow declined to comment for this story.)

Weiss lit into Apatow, “saying all kinds of stupid s---,” he says. His voice grows somber as he recounts the moment. He says Apatow told him that if he didn’t stop yelling, this was the end of their relationship.

“I didn’t stop,” Weiss says.

They haven’t spoken since.

Weiss, around this time, leaned into what he says was a fixation on the cliché of the tortured artist. He wrote and produced a web short, What About Weiss?, and a series, Why Not Weiss?, in both cases playing a funhouse-mirror version of himself, down to his increasing struggles with various forms of addiction. In the latter, his character ends up panhandling on the street. (Weiss admits that Apatow warned him against this type of writing—that he would become what he writes.) Weiss and a producing partner began work on a third, similar series, aimed toward TV, but that project never sold, nor did a one-hour stand-up special he’d recorded.

Losses were piling up. Weiss’s father died of congenital heart disease in 2016, and Shaun struggled to afford the burial. He began selling memorabilia, including an old Goldberg jersey from one of his films. He took a job in telemarketing. He failed, again, with a TV project, and then blamed his disastrous financial situation for the end of a longtime relationship. “I lost my mind,” he says. “I went crazy. My chest hurt, man.”

Buena Vista Pictures/Everett Collection

When Weiss’s apartment lease expired, he crashed with a friend … and then got into a fight with that friend. He left with nothing but his backpack and headed to a park, where he says he encountered some guys who looked like they might be dealers. He says he’d had a few drinks and he wanted something stronger than pain pills. He’d only tried cocaine a few times in his life, but at this moment he was interested. They didn’t have any—but they did have crystal meth.

After some deliberation, Weiss gave it a whirl. Anything to distract from the pain in his chest.

“The first time I took a puff of that,” he says, “it all went away.”

After lunch at Brent’s Deli, Weiss leads a tour down a rough stretch of Van Nuys Boulevard, where he says he spent most of the next couple of years in the throes of addiction. “Meth was not my drug of choice,” he says. “I was on heroin.”

Beyond places and a few faces, the details of his life at this point can feel like a Jackson Pollock painting: colorful but scattered, riveting and chaotic. “The drugs were so intense,” he points out. “And I’m 43 now. Your memory does start to go.”

But certain details stick with him. He says he pawned off Apatow’s laptop for $60. (“That’s a regret. Somebody has that f------ thing and has no idea what it means.”) After a couple of months, Weiss says, the van he was living in caught fire, so he moved to the streets. “[I would find] a new clique of people, and I’d hustle with them. And then something [bad] would happen, and I would have to leave to another neighborhood.”

He points out old encampments and hideouts and sleeping spots. The bathrooms where he’d shelter from storms. The stores where shop owners were friendly, and the others where they were not. Some strangers and security guards gave him kindness and hot chocolate on cold nights. Others beat him up. He remembers how some people buddied up to him and tried to help, only to get frustrated when rehabilitation didn’t come fast enough. The way he experienced it, he was completely alone; to his memory, no one from his family came looking for him. (Loretta disputes this. She says she worked with police for two years to track him down.)

Weiss points out the gym where he showered. The stores he stole from. Target. Home Depot. Gap. Convenience stores. He’d go to In-N-Out and wait for a cashier to call an order number, then grab the bag and take off. (“They had meetings about me, man,” he says.) High on meth and heroin, he’d rob power drills and jeans and batteries, and he’d sell them for cash. Then he’d turn that cash into more meth and heroin.

More than a few times he landed at Los Angeles County Jail—one of them for three months straight—where he says the guards once played a scene from The Mighty Ducks over the P.A. speakers. (He says officers often recognized him and treated him well, sometimes even taking him to McDonald’s on their way to be booked.) Inside, he learned to join a gang. “They basically court you,” he says. “I felt like I was meeting with an agency. … I went [with] South Side,” joining a Lainto clique. “They were better at sharing their food.”

PictureLux/The Hollywood Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

He describes with horror the one time he opted in to the two allotted hours of outdoor time, on the prison’s rooftop, and how first he had to undergo a body-cavity search. “I spent the whole two hours so f------ pissed that I’d been violated,” he says. “I never went to the roof again.”

Back on the outside, he says he would sleep sometimes in the sheds on the Home Depot parking lot. There was a 24-hour Denny’s where he could spend a few bucks on a meal and get some sleep at a table until he was kicked out. Between the drugs and the fear, though, Weiss says he would at times go weeks, months, with little more rest than occasionally nodding off. He became a ghost of himself, figuratively and physically, his once-sizable form reduced to near-skeletal proportions.

For a while, he was able to romanticize it all. “I [was] a street hustler,” he says. “A straight-up thug. And I played the part, man.”

But the fun didn’t last long. “It was bad,” he says. “I ran up against real guys.”

At one point he says he was beaten almost to death after a dispute about a trade: drugs for a (different) laptop. Then there was the gang member who he says terrorized him. “Every time he saw me, he would beat the s--- out of me and take everything I had.” That’s how Weiss lost his teeth.

Another time he found himself taking shelter under the awning of the L.A. Kings’ Valley Ice Center, where he recalled decades earlier training for The Mighty Ducks. “I used to look down on people,” he says, remembering himself at 16, driving around in his M3, thinking he was “better than the people on the bus.”

As an adult, though, he saw from the other side what kind of person he’d been. “Ten people walk into a 7-Eleven,” he says. “One of them will give you a dollar. One of them will tell you, ‘You f------ stink, you piece of s---.’ And eight of them will act like you’re not there. I didn’t know humans were like that.”

In his real-life story, the heroes were the people on the street who helped him. “I would have a diabetic [episode], my sugar would be low and straight-up bums were going into stores and getting me sodas—people who had nothing,” he says. “I’ve been humbled. Now I see every human the same. There’s no difference to me between Obama and a waiter.”

Pressed on how he possibly reached this point, he references a sort of hedonic scale—a measure of the pleasure a person feels in a given situation. An ordinary, healthy person going about an ordinary, healthy day is probably at about 80 out of 100 on that scale, he says. If something goes wrong and that person feels depressed, maybe that drops to a 50. If they fall in love and are about to have sex, that goes up to 100.

And: “Guy hits a thing of meth?” Weiss says. “Twelve hundred.”

He laughs. “That’s what you’re dealing with. How are you gonna get somebody to never want to feel twelve hundred again? It’s problematic.”

So, what ultimately worked for him?

“Without drugs,” Weiss says, “twelve hundred is attainable.”

In 2019, Loretta tracked down her brother, and she hatched a plan: Shaun would move to her home near Sacramento, detox and then piece his life back together with her support. She got medications from a hospital and housed Shaun for what she remembers was six weeks. (Shaun says he experienced it as six days). She provided him with food and cleaned up when he left human waste throughout her home—but eventually it all broke her. She says she dropped Shaun off at a Salvation Army center and wept the entire drive home. “I am a strong woman; I have handled many things,” she says. “And I was not equipped for that.”

Back on the streets, Weiss, high on meth, was caught in a thunderstorm. He broke into a garage, and then into the car inside, and he was arrested on a felony burglary charge. This time it was an old Hollywood friend who intervened. Natanya Ross had been a child actor in the 1990s as well (on The Secret World of Alex Mack); and she, too, had struggled early on with addiction, leading to homelessness. When she saw Weiss’s mugshot she was working in the recovery and treatment industry, and she called in a favor with a clinical program that helped get Weiss out of jail in exchange for his enrollment.

After that program proved not the right fit, Ross connected Weiss with another clinic outside L.A., which took him on scholarship. And slowly he found gains. He came to accept that Play ball, get out of here and go get high again wasn’t going to work. “The Twelve Steps became a big thing for me,” he says. “And I started praying every night for God to remove the obsession I had with drugs. I don’t know how to not want these things, so can you help me with that?”

More than religion, though, he found healing in social media, of all places. In 2020, a TMZ post about his state went viral, and though Ross says it took a while to convince Weiss to look at the overwhelmingly positive and concerned reception online—“I’ll read 30 [comments] and then one will be bad and I’ll freak out over that one,” Weiss says—eventually he looked. And after spending the better part of the previous decade destroying his old Goldberg fame, to the point, he says, that he “had that feeling that not one single person cared if I live or not,” now he saw “a national love-bombing.”

He struggled to comprehend it. “I can’t think of another instance where the internet got together behind a celebrity and, like, saved him like that,” he says. “Can you think of another instance when those powers worked for good?”

When Weiss realized what was happening, he felt that hit of twelve hundred. “It changed my chemistry,” he says. “I was so depressed and feeling so worthless. Then, to have thousands of people reach out to you? To give you love and support? My fans saved me. … How could I be so selfish when all these people are rooting for me? How can I let them down?”

Today Shaun Weiss resides at a sober living home in the Valley, but he’s searching for an apartment. He’ll get there. He’s begun to earn money again, legally, mostly by attending conventions and autograph signings. Which leaves him feeling conflicted. “Fans should have a free autograph,” he says. “But there’s a market for it, and I need to make a couple bucks.” Plus: “I get to meet supporters. They’ve taken the time to come out and they’ve been supporting me this whole time.”

He struggles to fully grasp that support. “Like, how beautiful is that?” he says. “To make a movie, and to touch people like that so many years later?”

He wants to get back to that life. In his room at the sober living home his walls are covered in notecards outlining his return: everything from stand-up bits (he recently did a 10-minute set) to scripts (he just shot his first movie in six years, playing a shattered Vietnam vet).

“I have 14 f------ things I’m trying to produce,” he says.

Courtesy of Shaun Weiss

Nothing is easy, though. A family member with whom he’s close recently relapsed from his own addiction, and there’s drama with a friend over some money that was raised to help Weiss out.

The difference between the present and the past: Now Weiss lets himself feel that pain. No diving out of the way. And in the pain there is a gift: the recognition of growth. In the past, he says, “I think I was just as addicted to volatility as anything.”

He’s also heeding Apatow’s warning from a decade ago. “When I sit down and write,” Weiss says, “I write about happy s--- now.”

A month and a half after our first meeting, Weiss limps back into Brent’s Deli. He still hasn’t figured out what to do about his hip, but he has put on some healthy weight. In the months to follow, his life will beef up in kind, as interest seems to be growing in his various projects and as he begins to land small but steady stand-up work. Increasingly, he finds himself thanking attendees at his shows. He feels himself moved nearly to tears as he makes people laugh again.

For now, though, he orders another pastrami and a diet cola, and this time he gives a wide smile to show off a full set of teeth, top and bottom. “These,” he says, “are the Porsche 944 of teeth.”

Upon hearing Weiss’s story, a dentist in L.A. hooked him up with the new smile (which otherwise would have cost around $100,000). But the installation has taken the better part of the past year, and it’s been grueling. “Every three months I’m going to the dentist to get my face ripped open,” he says. “And it takes a month to heal. … The first three days, I almost cut my f------ tongue off [trying to eat].”

“Not worth it. Just intense torture. To suffer the way I have suffered? Just to look cute in a selfie?”

He’s joking, of course, but he wonders whether perhaps, inside, part of him wanted to suffer. “I used to be really into the idea—the whole tortured artist thing,” he says. “A lot of guys feel like suffering has to be some sort of jumping-off point. And I don’t know now. I might swap the word suffering for experience. To say suffering is such a negative way to look at life. Experience is more rooted in wisdom, you know? And it means the same thing.”

The food arrives.

“Oh, man,” he says, his eyes lighting up, a hungry man ready to eat again. “I’m about to masticate the f--- out of this sandwich.”

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories:

• Seri Pak’s South Korean Surrogate Children Own the LPGA

• John Amaechi: ‘You Want Gay People to Come Out: Make It So It’s Not S----y’

• Steffi Graf Is Still Too Famous For Steffi Graf

• Michael Schumacher Is the GOAT. Michael Schumacher Is Absent.