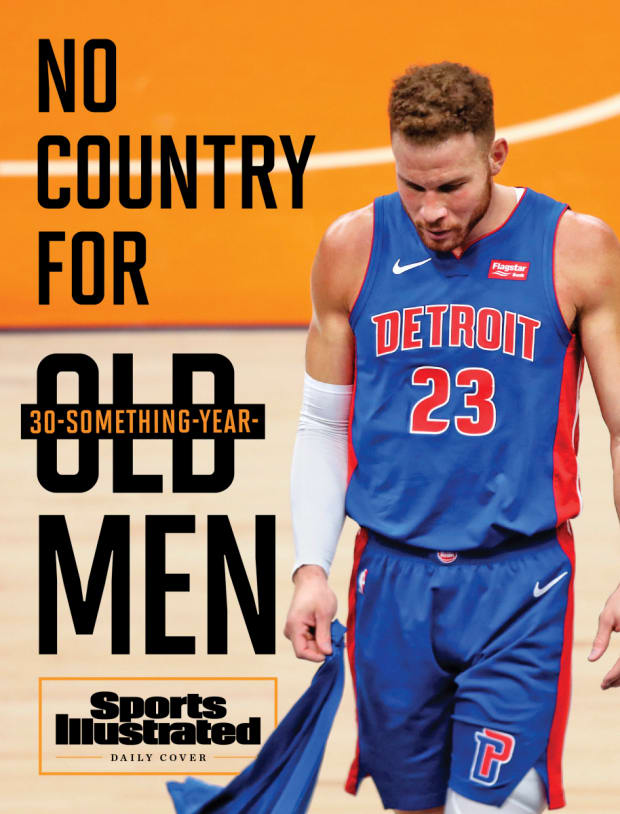

Blake Griffin and other players of a certain age are finding that in today's NBA, if you can't adapt, you can't fit in.

Back on Jan. 18, 2019, Pistons forward Blake Griffin needed hardly any time to establish he could do pretty much anything he wanted against an impressive Miami defense that night.

With the Heat fearing his scoring ability to start the contest, Griffin toyed with Miami’s help defenders, baiting them just enough to free his teammates for open looks. He tallied four assists in the first three minutes of the game, showing he’d make the Heat pay for not respecting the other Pistons on the floor.

Then, later in the first quarter—after Miami retreated to stay more closely attached to Detroit’s role players—Griffin applied pressure by putting on his scoring hat. Operating from the top of the key, he used a behind-the-back crossover to shed primary defender James Johnson, dribbled twice to get into the paint, then smoothly Eurostepped around Bam Adebayo at the restricted circle for a layup. From the right wing, he took a handoff, then dribbled into the paint and patiently lofted a floater that funneled through after no shot blocker stepped up to confront him. One possession later, Griffin lost control of the ball on a pump-fake at the arc, leaving the Heat defense scattered as a result of the busted play. Upon getting it back, Griffin capitalized on the wide-open lane by skying for an easy dunk.

Just like that, Griffin had notched three close-range baskets in a little more than 90 seconds, prompting Miami coach Erik Spoelstra to burn a timeout. Seven minutes in, Griffin had already shown to be a maestro, dictating action from the post, the wing and the top of the key, both as a scorer and passer. He’d finish with a quintessential Blake Griffin line: 32 points, 11 rebounds, nine dimes; all game-highs. Eleven trips to the line. An equal amount of time on the block and above the rim, where he was stronger and more athletic than everyone else. He even showed off some range in the 98–93 win, knocking down three triples.

Fast-forward exactly two years from that night, though, and you get something much different. It’s still the Pistons and the Heat playing, and Griffin is there on the court. Well, technically he is, at least.

Where the 29-year-old Griffin was dominant, running circles around the Heat, the 31-year-old Griffin is barely running at all. His jumping isn’t as high, or as frequently. He rarely shoots. When he does, they’re usually perimeter shots the defense wants Griffin to take. He no longer imposes his will, because he can’t.

That defeat a few weeks ago, in which he shot 2 for 8 for five points, five rebounds and one assist in 35 minutes, was merely one game. Yet looking at his full season—one that’s been so unproductive that the rebuilding Pistons have decided to sit him until they figure out his next step elsewhere—illustrates a harsh reality about the modern NBA: that there may not be a soft landing spot anymore for high-flyers like Griffin or Russell Westbrook, who fail to adapt as they approach the back end of their careers.

In previous years, Father Time often allowed his NBA guests a bit of a grace period. If checkout was at 11 a.m., players could typically have until noon or even 1 p.m. to gather their things and say their goodbyes.

The notion of having an “old-man game”—where a burly, skilled player like Griffin could back down defenders and launch fadeaways to slow things down and keep pace with younger, faster players—was common, if not completely embraced. For bigger ballhandlers like Boris Diaw, Mark Jackson and Magic Johnson, the style of play was something of a highway rest stop: a portion of the career that could bridge the stretch between a player’s prime and his last hurrah, where there was essentially nothing left to give.

Players have always gotten old. And players always will get old. But what once was a reservoir or a fountain of relative youth now seems to be drying up. Post-ups aren’t nearly as desirable in today’s efficiency-driven league as they were in the 1980s, 1990s or early 2000s. And between the improved science and the notion of load management, teams are doing more to boost their players’ longevity, perhaps reducing the need for as many transitional, old-man post-ups and clear-outs to begin with.

Much like a bone-on-bone injury, though, there’s been almost no cushion between those two career stages for Griffin, whose game seemingly aged 10 years overnight. One clear indication: After taking 45.2% of his shots at the rim in 2019–20, Griffin’s number has plummeted to a career-low 24.8% this year—the steepest single-year drop any star player has seen in the past 20 years, according to Stats Perform.

This isn’t to suggest that all decreases in shots around the rim are created equal. Miami’s Bam Adebayo, for instance, is a 23-year-old who is taking fewer close-range shots as he creates more offense for himself by efficiently operating from the middle of the floor. Still, it’s worth monitoring players like 27-year-old Lakers guard Alex Caruso and 31-year-old Eric Bledsoe, the hyperathletic Pelicans guard who’s struggled with his shot over the years. Since last season they’ve seen 12.7- and 21.4-percentage-point drops, respectively, in terms of how often they get to the rim, both among the biggest dips in the NBA this year.

Still, no player’s drop-off around the basket has been as concerning as Griffin’s. Without his usual explosiveness, Griffin, a player whose shot diet once consisted of 20.9% dunks, hasn’t jammed in a game since Dec. 2019. Instead, Griffin’s shots have come from much farther out—55.9% of his attempts have been three-point tries—with his average shot distance ballooning to a career-long 17.3 feet.

Given that Griffin has put his body through the basketball equivalent of Fight Club—a pair of concussions, plus multiple surgeries on each of his knees and a procedure on his right elbow, among other maladies—no one could blame him if he wants to play a less physical brand of basketball as he ages. Since his debut in 2010, Griffin’s been flagrantly fouled 48 times, according to Stats Perform, more than twice as many times as the 21 flagrants endured by LeBron James, the league’s next-closest player in that span.

The challenge here, of course, is that Griffin ... isn’t a good enough jump-shooter to subsist on that style of play. At 15.0% (3 of 20), he owns the league’s worst midrange shooting mark. And he connects on just 31.5% of his threes, too low a figure considering that he takes more than six triples per contest.

Getting better from the perimeter, much like Jason Kidd did in his early 30s, is the clearest way for a descending star to extend his career. But other adjustments have panned out in recent years, too. Vince Carter, who retired last year at the age of 43, readily embraced the idea of coming off the bench in Dallas, a move that represented a step back, but also allowed him to continue to serve in a lead scoring role with the second unit without breaking the starters’ flow. In that same vein, San Antonio’s Rudy Gay has loaded his Father Time parking meter with coins, extending his run by frequently playing “up” a position as a small-ball power forward. The 34-year-old’s adjustment helps give the Spurs more lineup flexibility.

While Gay isn’t as accomplished as Griffin, who can’t play up as a small-ball center because of his limitations as a back-line rim-protector, the Spurs swingman is one of the NBA’s best recent examples of a player reinventing himself. He began his career looking like the Grizzlies’ franchise player; one who would revel in playing hero ball by hoisting long, contested two-point jumpers. But around the age of 30, after a pair of wake-up calls—including trades to Toronto and Sacramento, where he suffered an Achilles tear—he started operating from different parts of the floor, putting more emphasis on efficiency.

A player like Gay flipping his narrative later in his career means there’s still hope for the star who seems most at risk of colliding into the same forces hindering Griffin: the 32-year-old Westbrook.

On the surface, invoking Westbrook’s name may seem harsh or premature, particularly because he is again leading the NBA in triple doubles and his Wizards are playing their best ball of the year.

Still, the same sort of downward trajectory in Griffin’s shot metrics exists in Westbrook’s numbers, too. More than half of the guard’s shots were at the rim last year. But now, just 40.3% are—one of the steepest year-to-year decreases for a perennial All-Star guard in the past 20 seasons.

Even when Westbrook does drive, he’s worse at finishing at the play than he’s ever been before, logging a career-low 39.3% shooting mark, and with more turnovers than assists—an imbalance he’s never had as a driver. And when he gets to the line, which he’s doing at one of the lowest free-throw rates of his career, he’s converting there on just 60.8% of his tries, the worst mark in his 13-year career.

Taken in full, you get the least efficient season of Westbrook’s career. Dead last in the NBA in true-shooting percentage—91st out of 91 —among volume-shooting veterans. Win-share totals that have plunged into the negative. Pick almost any statistic, and you’re likely to end up with the same downward-trending result.

Like a bulb with bad wiring, Westbrook is maddeningly inconsistent, randomly flickering between being brilliant one game and brutal the next. The brilliance was there during a stretch last season, when Houston moved exclusively to small-ball, opening up the floor for Westbrook to drive. He abandoned the long jumpers, attacked the rim hard and averaged 32.1 points, 7.8 boards and 7.0 assists over a 75-day span.

Yet he plays with a defiance, often trying to force his way past defenders in one-on-one matchups, even though he can’t get by many of them anymore. Westbrook sometimes plays right into the defense’s dares to take wide-open jumpers, despite being one of the league’s most brutal jump-shooters. Unlike Wade, who made up for his lack of shooting by being an aggressive back-door cutter, Westbrook mostly stands still when he doesn’t have the ball, making for stagnant possessions. And Westbrook averages more turnovers than any player, even though he shares ballhandling duties with Bradley Beal.

Given the breakneck, Sonic-like pace Westbrook has always played at, it’s not surprising that we struggle to imagine what a slower, more controlled version of his game would look like—or whether he’s even capable of making a graceful transition once his athleticism wears far thinner. Still, given the long goodbye stars usually enjoy—since 2000, five-time-and-up All-Stars retire, on average, after 17 years of service and at age 37, per Stats Perform—whatever transpires with Westbrook will be enlightening.

The case with Griffin, who was still dominant on a regular basis just two years ago, is just as interesting.

Because Father Time is clearly on his way to Griffin’s room. The only question is whether he’ll escort the 31-year-old out, or give him a chance to exit more gracefully, on his own terms without making a scene.