For the past two decades, Saban and Pete Jenkins have been connected by their shared vision of a bruising game. Some might say Jenkins is Bama’s secret weapon.

At 80 years old, Pete Jenkins is spry for his age. He shuffles about, his back arched and arms awkwardly hanging by his side, and maybe he’s a touch slow in climbing the two flights of carpeted stairs in his home, but he’s no slouch.

His days of weight-room clanging long gone, he keeps in shape by briskly walking and working out with elastic bands. He travels more than a dozen times a year, and not for a beach getaway or Carnival cruise. Jenkins instead keeps a busy annual circuit of tutoring the next wave of great defensive linemen. These days, he is only a part-timer, paid handsomely by college teams as a consultant and NFL players as a personal trainer.

He is an artist in defensive line technique—hand placement, feet positioning, eye focus. His paintbrushes are decades-old technical videos, his canvas the players themselves and his work studio a loft office atop those carpeted stairs—a “sanctuary,” as one of his buddies describes it. It’s his hideaway, a football coach cave on the second floor of his and wife Donna’s quaint bayside home about 15 miles east of downtown Destin.

Jenkins creeps up the stairs, crosses the top-most step and moves into his work station, which includes a large television and two flat-screen computer monitors resting on a desk. The walls are covered in memorabilia from a 57-year career as a journeyman defensive line coach. There are reminders of the 11 colleges at which he has coached and the more than 40 defensive linemen he has helped send to the NFL.

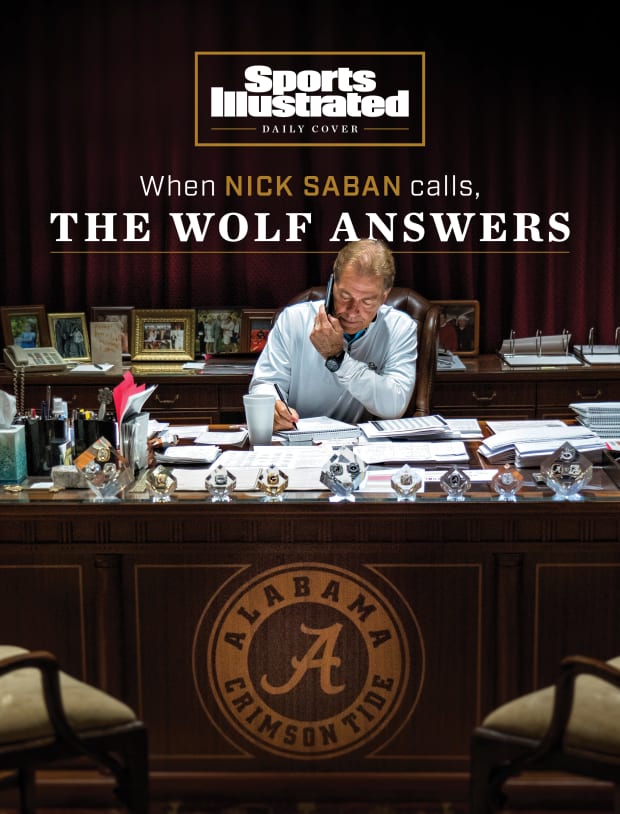

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

The loft is set in traditional decor. Lamps with pull chains. Armchairs with sleeves. It’s like going back in time, except for the modern pieces of electronics. Taught by his son, Jeff, Jenkins can splice videos over two separate computer monitors. He clicks a few buttons on a keyboard and pops up side-by-side still-frame images of defensive linemen operating the identical drill, 35 years apart.

Few coaches have retained their relevance in a sport across nearly six decades. Even fewer are as cherished and integral to the industry at this man’s age. The story of Pete Jenkins is vast and wide. His influence has touched so many parts of college football, the long branches of his coaching tree stretching into nearly every conference and a dozen of the sport’s blueblood programs. Master of the D-line. Greatest of all time. One of the founders of the 3–4 defense.

But of all his accomplishments and his relationships, there is one few really know about, one that he doesn’t often crow about.

“I don’t think it’s easy for Nick Saban to have long-term relationships, but he does with Pete,” says J.T. Curtis, a Louisiana high school coach and longtime friend of Jenkins.

For the past two decades, Jenkins and the Alabama coach have been engrossed in a symbiotic relationship, an emotional connection between two men connected by their vision of a bruising game. Jenkins says he’s indebted to Saban for bringing him back to LSU, a school Jenkins previously coached at for more than a decade and a place where he still owns a home.

Saban is indebted to Jenkins for a great many things. His deep connections in Louisiana helped the coach build a powerhouse in Baton Rouge and has since repeatedly turned to Jenkins to construct some of the game’s fearsome defensive lines.

Jenkins wouldn’t call himself Saban’s secret weapon, but others might.

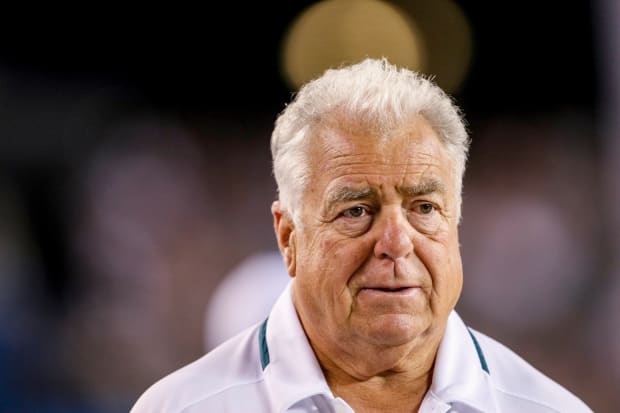

Drew Hallowell/Getty Images

On a cool October day earlier this year, Pete Jenkins knows his visitor is arriving to discuss his relationship with arguably the greatest coach in college football history. He is prepared, holding multiple marked-up notebook pages with what he says are the characteristics that make Nick Saban the best.

Hard worker. Great communicator. Forgiving (yes, he says, it’s true). Compassionate (yes, this too is true). Holds everyone accountable. Excellent talent evaluator. Intelligent. Saban is smart enough that he would be successful in any field, including the political realm, Jenkins says. “If he were the president of this country, it’d be a better country.”

If anyone knows Saban, it is this man. He’s been one of the longest-standing coaches in Saban’s orbit, going on 22 years.

“I’ve always respected Pete because he is a football guy,” Saban says. “I think he’s old-school like me when it comes to how you develop players and how you do things.”

Jenkins is Saban’s Wolf.

You know, the “Wolf” character from the Hollywood hit Pulp Fiction? Actor Harvey Keitel portrays a skilled fixer whose talent is solving problems. In the movie, The Wolf is called into a situation where he must direct others to efficiently and quickly dispose of a dead body. Jenkins isn’t disposing of anything, but he does find himself, multiple times a year, on the other end of a phone call with Saban, who summons him to Tuscaloosa to fix Alabama’s defensive front problems.

The calls come at various times. After the regular season. Before spring practice. In the middle of preseason camp. In the heat of the summer. A few years back, Saban phoned with an emergency. The Crimson Tide, preparing for the Citrus Bowl against a Michigan team that ran the ball quite well, needed to repair cracks in its front.

Get here now!

Jenkins, who was training NFL draftees in Dallas, boarded a plane sent by the university. He arrived at the Alabama facility, was handed a gift bag from Saban’s secretary and was hurriedly ushered into a dark meeting room where the coach himself was leading a film session. Jenkins glanced inside the gift bag to find peanuts, crackers, a few chicken breasts, his favorite drink Coke Zero, and some bottles of water.

“I remember looking in there and I thought, ‘I might be here a while,’” Jenkins cackles.

During these trips, Jenkins doesn’t work with players. That’d be an NCAA violation. Instead, he coaches the coaches. He identifies technical weaknesses from watching hours of Alabama practice and game footage of its defensive line before making suggestions using his own teaching methods and videos. Those who have been around Jenkins call him the best teacher they have ever seen, a master of detail on the most granular level, right down to the positioning of a defensive line coach during a drill.

“He has to stand here,” Jenkins says, “so he can have the best angle to evaluate his players’ techniques!”

“He’s had average college players and made them great college players,” says Terry Bowden, who hired Jenkins at Auburn in the 1990s. “Nick appreciates teachers of the game and people that have the knowledge and authority. He teaches kids to be fundamentally sound.”

Jenkins has a standing trip to Tuscaloosa each spring to teach the new defensive staff, or reteach the old staff, the “Pete Jenkins Way,” says Karl Dunbar, a former Alabama assistant and Jenkins protégé who is now a defensive line coach for the Steelers.

And what exactly is the “Pete Jenkins Way”?

“Pete coaches a different brand of football. I try to coach the same way, teaching guys to use your hands and leverage to defeat blocking schemes. It’s a lost art,” Dunbar says. “A lot of guys don’t teach guys how to use their hands to take on blocks. Coaches now want guys just to go upfield. But if you can’t control the gap, you miss out on a lot of things. When you’ve got guys who can defeat one-on-one blocks, that’s the difference.”

Dunbar describes Jenkins and Saban as “kindred souls” who view football in a similar way. For years, Saban has built the foundations of his teams on the defensive line. Win the line of scrimmage, win the game. Despite the evolution of offensive football, that’s still the mentality.

His teams often control the front defensively using a Jenkins philosophy built around the old coaching adage of “the little things.” Jenkins is a technical coach, not schematic. In football’s one-on-one trench warfare, he is the five-star general, not positioning his troops or drawing battle plans but teaching them how to properly aim and accurately fire.

“I think technique is most significantly important on the offensive line and defensive line,” Saban says. “Pad level, hand placement, balance and body control. Pete is the absolute best at [teaching] all of those things.”

Saban was the first to begin using Jenkins as a consultant. The decision led to a lot more work for Jenkins. Saban’s former assistants who became head coaches copied their former boss’s plan. They all began to use Jenkins as a consultant, too, chasing the magic recipe for success. (Saban likes to joke that he “subsidizes” Jenkins’s retirement.)

Jenkins has a devoted following. Many of them, now college and NFL D-line coaches, started an organization years back called the Two-Gap Club, a nod to Jenkins’s teaching philosophy. His linemen align straight up across from an offensive player, or slightly shaded, and are responsible for the gap to the left and right: two-gap. The organization is dozens deep and includes some of the sport’s most high-profile D-line coaches. Jenkins has been around long enough to have instructed the sons of fathers he taught back in the 1980s and ’90s.

His D-line tree is so profound that Andy Reid’s search for a new Eagles line coach in 2007 landed on a group of candidates with one similar characteristic. They were all “Pete Jenkins guys.”

Finally, Reid figuratively threw up his hands.

“Why don’t we just hire this Pete Jenkins fella?”

Jenkins was the Eagles' defensive line coach from 2007-09.

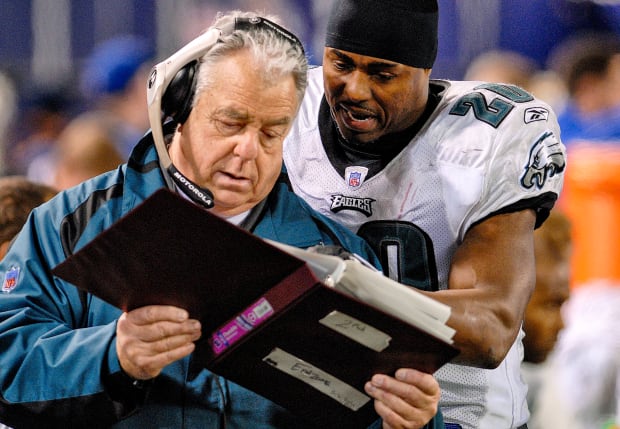

Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated

In 1999, Hank Tierney was a high school coach in south Louisiana preparing for his first visit from the new hotshot head coach at LSU, Nick Saban. Before Saban entered his office, Tierney scribbled a name in large letters on his chalkboard.

PETE JENKINS.

Saban was amassing his first staff, and Jenkins had called Tierney with a favor: Put in a good word for me. Maybe Saban would see Jenkins’s name on the board, Tierney thought, and the two would strike up a conversation, at which point Tierney could boast about his old friend.

The plan didn’t go so well. Saban didn’t mention the name at all. They talked very little about Jenkins. The coach left and Tierney immediately phoned his friend. “I don’t think I did too good for you.”

Over the next few days, more people around LSU and south Louisiana recommended that Saban bring back Jenkins, who worked as an assistant at LSU for 11 years ending in 1990. And so he did.

Jenkins’s two seasons as Saban’s defensive line coach in Baton Rouge supplied the foundation of their relationship. They recruited together. They sculpted the Tigers’ defense together. They worked long, long hours together (during one of those years, the staff worked 48 of 52 weekends). That LSU staff under Saban in the early 2000s included many young bucks who are in high-profile jobs today. Will Muschamp. Jimbo Fisher. Mel Tucker. Then 60 years old, Jenkins was the old man of the gang, the only one who could really josh around with their taskmaster. He could push Saban’s buttons, in a good way.

Once during a staff meeting, Saban joked with Jenkins about his age, suggesting he wished he had the extra years of wisdom.

“Hey, Coach,” Jenkins replied, “I wish I made your salary!”

The room fell silent. The other assistants froze. And then, Saban cackled in laughter.

After the 2001 season at LSU, Jenkins retired for the first time. Saban himself hosted his retirement party at a restaurant in Baton Rouge.

“The nicest I’ve ever seen Nick was at Pete’s retirement party,” Tierney recalls. “You should have seen him. He was telling jokes!”

Jenkins brings out something different in Saban. The steel armor subsides and a more vulnerable Saban emerges, those close to them say. He even has a nickname for Jenkins: Petey. Petey can attend an Alabama game whenever he wants, as a guest of the head coach. But don’t get it confused, Jenkins says, they don’t pal around together as dinner mates.

“We may be the odd couple,” he says, “but we ain’t buddies. When he calls me, he calls me to come to work.”

This isn’t unique to Jenkins. Saban does this with virtually everyone.

“I don’t chat with anybody,” the coach said during his radio call-in show last week. “I don’t talk to people throughout the week. Maybe Miss Terry [Saban’s wife], if I am lucky, but I don’t see anybody except our staff. My days are planned out. I don’t have a lot of time to say, ‘Imma call my buddy and see how he’s doing.’ I would love to do that, and I wish I had time to do it.”

This connection of theirs dates further back than those days in Baton Rouge. Unbeknownst to one another then, Saban and Jenkins, separated by 10 years, studied the defenses of the 1980s Giants, led by coach Bill Parcells, coordinator Bill Belichick and star linebacker Lawrence Taylor.

Those Giants defenses, dubbed the Big Blue Wrecking Crew, helped the team win two Super Bowls and three NFC East titles while popularizing the 3–4 defense.

“A lot of our thinking, Nick and I, was born and bred in New York,” Jenkins says.

Jenkins’s connection to Alabama goes even further back. He was born and raised in Warner Robins, Ga., not too far from the Alabama state line. His mom was a homemaker and his dad was a butcher. He’d spend each Saturday scrubbing the butcher block, an objectionable task that convinced him of something: Don’t become a butcher. Jenkins played football because it was the only outlet at his high school where he could, as he says, “give someone a lick” without getting in trouble.

He traces his early mastery of defensive line play to Alabama as well. His mentors were former Giants D-line coach Lamar Leachman and Ken Donahue, who worked as an assistant for 19 years under Bear Bryant. In 1971, Bryant offered a recruiting job on his Alabama staff to Jenkins, then a young assistant coach at North Alabama. The position included plenty of travel, long nights on the road and no on-field coaching. Jenkins turned it down.

“As the years went by, have I thought about it? Yes,” Jenkins says. “I could have worked for two of the greats in the game.”

John Iacono/Sports Illustrated

Three days into a five-day consultant visit to Tuscaloosa, Jenkins sounds exhausted.

“Just got back to the hotel,” he says in a huff.

Don’t let him fool you; he loves this stuff. When Nick Saban calls, The Wolf answers.

He spent nearly all of last week at Alabama as the top-seeded Crimson Tide (12–1) began practice ahead of the College Football Playoff. For the 11th time in the past 13 seasons, a Saban program is alive to win the national championship in mid-December—arguably the greatest dynasty in the modern history of college football with six titles over that span.

And to think, an 80-year-old semiretired defensive line coach has contributed in at least a small way. Last year during a visit to Alabama, Saban asked Jenkins for advice before the top-five regular-season clash against Georgia. Well, they’ve got a short quarterback, so you’d better tell them to get their hands up.

Alabama’s defensive linemen deflected four passes in the game and the Tide rolled, 41–24. Jenkins got a call the next day. It was Saban. He thanked him.

If he’s anything, Jenkins is fiercely loyal. There is no sharing information he learns on a visit to one program with another. In fact, in 2016 and ’17, he came out of retirement for the last time to join Ed Orgeron’s staff in Baton Rouge as full-time line coach. He went roughly 18 months without visiting Saban’s staff during that time.

“He was pissed,” Jenkins says with a laugh.

Jenkins really began his college consulting service after his three-year stint with the Eagles ended in 2009. In all, he’s been hired by 41 college programs. He’s visited eight programs in the past year and three of them are in the Playoff: Alabama (three visits), Georgia and Michigan.

Back in his loft office, Jenkins’s schedule is laid out on a desk against a far wall. Colored markers are used to denote trips each week. In January and February, he trains NFL-bound college players in Miami or Dallas, usually. In March through May, he visits colleges. In July, it’s back to training the pro players. And then there are college camps in August.

In between those trips are visits from his disciples. At one point or another, they make their way up the two flights of carpeted stairs and step into this man’s second-floor sanctuary. It’s almost a ritual of sorts, Jenkins flicking on the two-screen workstation to show 40-year-old clips of some of his first great players like Leonard Marshall and Karl Wilson, juxtaposed next to his modern-day trainees like Justin Ellis and Dalvin Tomlinson.

“The game has changed all over the field except in the box,” Jenkins says. “It’s how to defeat blockers, gaining separation, shedding and making tackles. That’s why I’m still relevant to people today. It’s the same as it was in 1964 when I started.”

Many of his former players, now coaching, still send him clips on a weekly basis, seeking help about a technique—maybe it’s hand placement or foot positioning. That includes Texas defensive line coach Bo Davis.

“They don’t make ’em any better than Coach Pete,” says Davis, a former Jenkins player at LSU who nearly quit college football after the school fired the entire staff, including Jenkins, in 1990. “He told me then, ‘Just because you’re mad at the bus driver, don’t get off the bus.’ He’s the reason I continued to stay and play.”

In that sanctuary of his, Jenkins calls downstairs to his wife and up comes Donna Jenkins with glasses of water for her husband and their guest. The two have been married for 54 years and have two children, both grown and long gone from their home.

Donna is well aware of her husband’s football crush on the Alabama head coach. After all, he has saved on his phone a 19-second voicemail from Saban. After one particular consulting trip to Tuscaloosa, Jenkins left disappointed in his work. He felt like he let down Saban. So ashamed, he left the coach a handwritten note on his desk expressing his apology.

Days later, Jenkins missed Saban’s phone call, and the coach left him that voicemail.

“Hey, Pete,” Saban begins, “sorry I missed you. Don’t have a heavy heart. No reason to apologize.”

Saban is at the center of Jenkins’s football sanctuary here. The largest framed piece of art in the loft is a three-foot-high photo of Jenkins and Saban coaching together on the sideline of an LSU game—a gift from the coach presented to Jenkins at that retirement party in Baton Rouge.

Saban isn’t a man who routinely delivered superlatives about much of anything. He’s not a guy who dishes out compliments often. But during a brief interview with Sports Illustrated about Jenkins, Saban gushes.

“He’s probably one of the best defensive line coaches, if not the best defensive line coach, that I have ever been associated with,” he says.

Jenkins’s eyes well up when he hears the comment. In many ways, this is what’s all been about, to have the blessing from the greatest of all time.

Jenkins rises from his workstation to begin the hike down his carpeted stairs. He reaches to grab his smartphone and slides it into his pocket. Even if it’s for a fleeting moment, The Wolf can’t risk missing a call from the man. Jenkins laughs about those phone calls. As he does with everyone, Saban calls from a blocked number. When Jenkins sees that flash across his phone, he knows who it is.

And he knows what’s coming.

“Pete, here’s what I need you to do,” Saban always starts.

“I hope,” Jenkins says, “he doesn’t ever call and say, ‘Pete, here’s what I need you to do—go kill somebody.’ I don’t want to spend the rest of my life in prison, because I’d kill the son of a b----.”

• He Nearly Died on ‘Drive to Survive.’ Now He’s Faster Than Ever.

• Tom Brady Wins the 2021 Sports Illustrated Sportsperson of the Year

• 'He's Made the Difference': LaMelo Ball Has Charlotte Buzzing Again