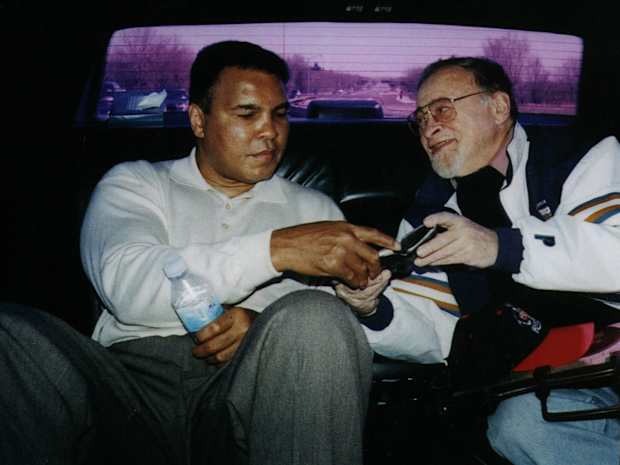

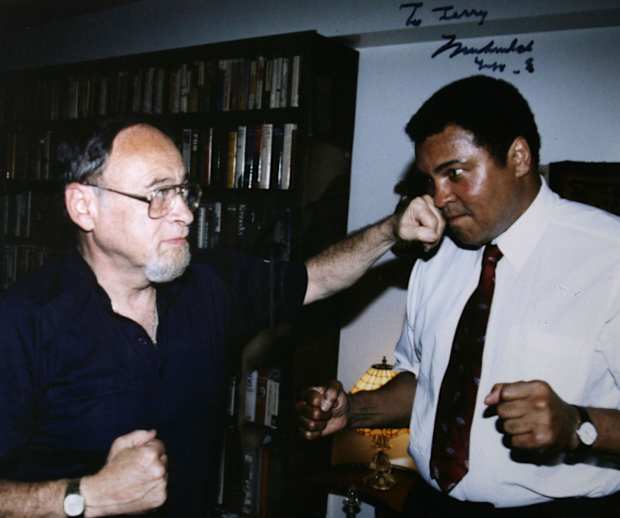

Jerry Izenberg has been writing about sports for almost 70 years, but he hasn't grown closer to any of his subjects as he did with Muhammad Ali.

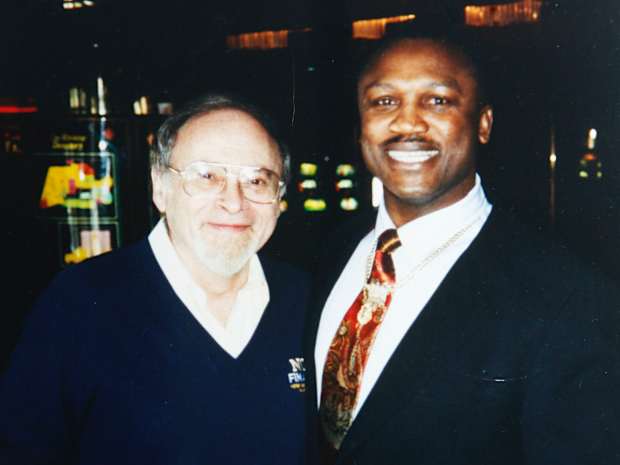

The 90-year-old sportswriter wants to make a point about Joe Frazier, almost 50 years after the boxer’s most famous fight. “Did you know that Joe’s hook came from a deformed arm?” Jerry Izenberg asks, in the way that only Jerry Izenberg can. He’s backed by seven decades of firsthand sports history, thousands of championship fights and Super Bowls and the moments that came before them. His insight remains the kind gleaned only by those who saw these careers unfold up close.

So, about Joe Frazier and that arm: the young boxer worked on a farm back in South Carolina, and one of his jobs was to chase the family’s prized hogs back into their pens. One day, he fell while giving chase, breaking his left arm. Frazier never regained his full range of motion with that limb, in part because his father asked him to put off surgery, which only made his left hook more compact and thus ultimately more dangerous. Many of his 27 career knockouts resulted from the damage inflicted by that deformed arm. “I used to think that hook was alive,” Izenberg says, in that Izenberg way. “I told Frazier that once. I called it the Philadelphia Left Hook.” Frazier, Izenberg says, threw that punch better than Ali, Rocky Marciano and Joe Louis.

Such is the life of Jerry Izenberg, the sportswriter who never stops writing, who comes to mind every time there’s an anniversary of an iconic sporting event. That’s because, in all likelihood, Izenberg was there to capture it, whether before, during or after—and sometimes, most times, for all three. He once told his wife Ali ranked among his five closest friends in the world. She asked him to list the other four; he couldn’t come up with another name.

The scribe can tell stories like this for hours. There’s a reason he’s enshrined in 16 separate halls of fame, and it’s the same reason he’s still writing 69 years after graduating from Rutgers-Newark, or one year after he started as a copy boy at The Star-Ledger, where he’d send edited stories in pneumatic tubes up to the composing rooms. A young Izenberg made something like 10 coffee runs a night, swept floors and learned a trade—the storytelling kind. He later served in the Korean War and worked at the New York Herald Tribune, his desk near the era-defining columnist Red Smith.

Izenberg would give Smith’s career a run. He covered the first 53 Super Bowls, 55 straight Kentucky Derbys and the last five horses to win the Triple Crown. He wrote about boxers from the 1960 Olympics onward, befriended Vince Lombardi and Pete Rozelle, penned pieces about rodeos and fly fishing and point-shaving scandals. He hosted television shows, wrote TV narration and produced documentaries. And, talk about hazard pay, he even spent a season covering the Mets.

It’s those moments he’s still telling. And those moments he’s still chasing.

Which brings him back to Frazier and Ali and their first bout, the forever-billed Fight of the Century, held 50 years ago, on March 8, 1971, at Madison Square Garden. After Frazier won by a unanimous but controversial decision, Izenberg took the train to Philadelphia the next week. Upon his arrival at Frazier’s gym, the champion suggested they head out for some sandwiches. And at the neighborhood deli, they bumped into several children, all fans, who chanted Frazier’s name and caused his face to “light up like a Christmas tree.” Frazier signed pictures and implored the children to stay in school, listen to their parents and not hurt anybody.

Eventually, one of the kids chimed in. “Well, my daddy says Muhammad Ali was drugged.”

Frazier, Izenberg laughs, about turned white. “He was enraged.” He bent down on one knee, looked the boy in the face and said, “You go home and tell your daddy, he’s right.” Frazier paused, then continued. “Muhammad was drugged. I drugged him with a left hook.” Then Frazier threw a giant left in the air for emphasis, while Izenberg scribbled away. The kids scampered off. Frazier locked his gaze on Izenberg and spilled forth “words that were prophetic for the rest of his life.”

“You tell me,” Frazier said to the writer. “What [do] I got to do?”

“And there’s nothing he could do,” Izenberg says now. “Because that shadow of Muhammad Ali stayed in his life forever.”

So many stories. Many are captured in one of Izenberg’s best books, Once There Were Giants: The Golden Age of Heavyweight Boxing, which will be rereleased in paperback in late April to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the first Ali-Frazier fracas.

Izenberg recalls the second bout between the men, the one Ali won almost three years later. Fight of any one century this was not. “Horrible, terrible,” Izenberg says of the contest Ali won by unanimous decision. And he went to cover the meeting to complete the trilogy, the “Thrilla in Manila,” in October 1975. Izenberg chronicled that seminal sports moment, too, as Ali taunted Frazier, calling him a “gorilla,” among other insults, until Frazier’s son was beaten up at school by peers following Ali’s lead. The father began to plot his revenge.

Izenberg can still remember, vividly, after Round 14, when Frazier’s corner cut his gloves off. Ali could hardly walk at that point. He stood up, took three steps forward and fell down. “He collapsed because he didn’t have any strength left,” Izenberg says. If only Frazier had walked out for that round.

The longer Izenberg continues on this way, the more it becomes clearer these moments—and the stories they produce—are what drive him. Even now. It’s not the anniversaries, the accolades or the awards. “I still have so many stories in me,” says an author who has published 15 nonfiction books and a novel, his first, last year. After the Fire: Love and Hate in the Ashes of 1967 is an interracial love story between a Black woman and an Italian man that’s set up right after the Newark Rebellion in 1967.

The novel was drawn from parts of Izenberg’s own life. He lived and toiled at keyboards for years in Newark and married his longtime girlfriend, Aileen, a Black woman who worked as an administrator for the city’s public schools. Together, they founded the Newark Project Pride organization, raising funds through an annual college football game to help send more than 1,100 students to college. Izenberg also helped introduce white America to Black college football with a documentary on Grambling’s powerhouse program that he produced with Howard Cosell. He befriended Negro League baseball stars. He saw the need to address social injustice in sports long before the world finally caught up to his worldview.

Izenberg has tales about all that, too, just like the Fight of the Century, now half a century removed. He’s not unlike Frazier and that famous left hook in a way. The 90-year-old sportswriter took what he lived, what he saw and what he asked about, and he channeled his experiences into his craft—one of the most prolific careers of any writer whoever happened to cover sports. That’s what satiated him then and what keeps him going now, as he continues to write and tell stories in a life that has been long sustained by two intertwined pursuits.