The father who worked in fashion, the mother who fronted an avant-garde rock band and the son who is both nothing and exactly like them.

The other day when Bill Marpet saw his son, Ali, he was taken aback when he noticed his boy dressed up in a black Polo shirt with a red emblem on the chest.

This was far nicer than Ali usually dressed; for most of his life, he had revelled in the art of the hand-me-down. Once, on a family vacation to Jamaica on New Year’s Eve, Ali donned his version of formal attire: a T-shirt that read AT THE CORNER OF HAPPY AND HEALTHY that he proudly announced was free of armpit stains. That fashion sense that dated back to his toddler years. Once, when Bill was doing the laundry, he asked Ali whether a pair of pajamas he was holding belonged to him.

“Yep, them’s are mine. The ones with the holes in ’em.”

Bill laughs. He’s one of the country’s preeminent fashion videographers. If you’ve seen clips of models tiptoeing down the runway during Fashion Week, there’s a good chance Bill was the one who taped it. There’s a good chance he was the one who suggested to the designers how the models should walk to accentuate the wardrobe. Bill looks the part, with long, silver hair and earrings; leather jackets; and shirts unbuttoned in a way that looks effortlessly cool—the kind of thing a lay person could not accomplish without a few hours of time and a T-square. He knows Calvin Klein. And yet, “I still don’t think Ali has a T-shirt that he’s actually bought himself,” Bill says. He was right. When he asked Ali where the new threads had come from, he admitted he’d hocked the Polo shirt from a former teammate, Beau Allen, when Allen had cleaned out his closet.

Ali’s mom, Joy Rose, is a museum director. She’s also a singer, with a hit that made Billboard’s dance chart for a month back in 1988 and a music video that made its way onto MTV. She studies the emerging field of motherhood academically and later formed an avant-garde rock band called Housewives on Prozac.

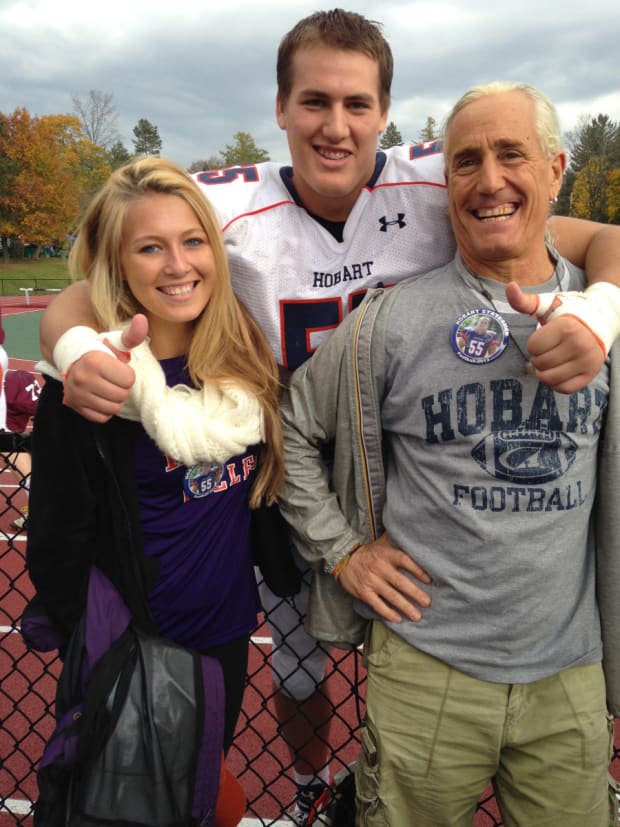

In that way, it may seem like Ali was the apple that fell far from the tree, a man rebelling from stylish rebelliousness. As he takes the field Sunday against the Chiefs, he does so as the Buccaneers’ most valuable commodity on the offensive line; the latest in a lineage of stout interior offensive linemen that made up the bedrock of so many of Tom Brady’s Super Bowl teams in New England. He is fifth in the NFL in pass block win rate (95%). Pro Football Focus rated Marpet the seventh-best guard in football this year. He has not given up a single sack. But he views his rise from obscurity at Division III Hobart College as a direct product of his parents’ mastery of their own crafts and their individual dedications.

How does a kid who didn’t start playing football until his junior year of high school, who needed to learn how to run the 40-yard dash the weekend before a scout came to work him out in college, who went from eyeing a post-college stint playing American football in Europe somewhere—or finding a way to utilize his economics degree—to becoming a second-round pick and, eventually, one of the highest-paid offensive linemen in the sport?

“I think the absolute and total commitment to a cause that they showed just rubbed off on me,” Ali said last week after practice. “It wasn’t them saying, Hey, find something you’re passionate about. It was just about them being them. They had a pursuit and a passion and me seeing that was probably the best thing they could have showed me.”

Ali’s world began to shift around high school when one random weekend day, Bill argued that he should drive with him to Yonkers, N.Y., and try out for an AAU basketball team named the Minutemen. Ali was functional on the basketball court but would rather have been hanging out with his friends. Bill said it would be a new experience and that he should give it a shot.

The result, Bill says, was a “big, slow white kid” lumbering around the court amid a sea of great athletes. But he made the team, carved out a role and worked his way into the starting lineup. Fast-forward a few weeks, and Bill was sitting next to a young-looking coach scouting the player that Ali was defending at an AAU tournament in Orlando.

“Hey,” the coach said, “your kid is playing pretty good.” It was future Celtics coach Brad Stevens, then recruiting for Butler University.

Ali would later tell his dad that his time on the Minutemen changed his life. It wasn’t hard to see that Ali had finally inherited that familial trait—an ability to develop a love for something and approach it at full speed without a safety hatch. Basketball became football (he preferred to, quote, “hammer people” which was frowned upon on the basketball court) and would quickly color his approach and choices to some now-definitive moments in his life.

He went to Hobart College in Geneva, N.Y., and played on the football team. He says he felt at home because it was a group of people who saw the world the way he did. Of course football was not a means to an end in the Finger Lakes, where only one statesman had reached the NFL over the previous 100 years (Fred King, who played a single game for the Brooklyn Football Dodgers in 1937). People showed up to practice every day because it felt right. Because they loved it. Ali was a big left tackle bullying defenders miles downfield on long screen passes, having the time of his life.

“If you’re playing D-II or D-III or NAIA you have to love football,” Ali says. “You’re not doing it for any other reason besides love.”

At the end of his junior year, a scout from BLESTO (a centralized draft scouting service that a number of NFL teams subscribe to for information on out-of-the-way players) was coming to campus to hand out Wonderlic tests and time players in the 40-yard dash. Ali was supposed to go visit one of his friends at Bucknell that weekend but opted for a two-pronged approach that would change the fortunes of Division III players to come and the offensive line-needy Buccaneers: 1) skip a fun weekend at Bucknell; 2) learn how to run a 40-yard dash.

“I said I think you better stay at Hobart and, like, get big and fast,” Bill remembers telling him.

Ali suddenly started sounding like his dad. Bill began running around the East Village with a camera taping obscure bands at CBGBs at the end of the 1970s. He didn’t realize he was at the epicenter of a cultural movement, witnessing the rise of Talking Heads and Ramones (he preferred filming Richard Hell and the Voidoids and Television; David Byrne, the Talking Heads’ frontman, was too shy). There was just something innately telling him he needed to be there and do it well. So he did.

That week at Hobart, more than three decades later, despite any tangible reason to believe it would pay off—no Division III player had been drafted in more than a quarter-century—Ali decided to take the BLESTO visit with an intense degree of seriousness.

“It’s sort of ... it really is unbelievable,” Ali says. “I feel like I had some good people around me, and then this path just opened up based on me loving to play the game. It was just about taking the steps I could take to become the best player I could be.”

After scoring high on the Wonderlic and logging a respectable 40-time, scouts began crawling through Hobart practices with regularity. One day, Ali fielded a recruiting call from an agent and called his dad to talk about the experience, wary of whether the attention he was receiving was even legitimate.

“He was like, Dad, this guy Steinberg calls me. I dunno. I wrote it down. Steinberg sports.”

“I asked him, ‘Leigh Steinberg?’ ”

“He said, ‘Yeah, why? Do you know him?’ ”

“I said, ‘Ali, have you ever seen Jerry McGuire?”

“ ‘Yeah.’ ”

“ ‘That movie is about Leigh Steinberg.’ ” (Ali did not end up signing with Steinberg, choosing Andy Ross of Select Sports Group.)

“That’s when we started hoping that maybe Ali would get an undrafted free-agent deal,” Bill says. “Maybe land on a practice squad somewhere. Then he makes the East-West [Shrine] game. Then he makes the Senior Bowl. Then he got into the combine. He always worked so hard. He just set goals for himself.”

Bill spent the week at the Senior Bowl soaking it all in.

“Man, there is a lot of friggin testosterone around here,” he remembers telling a friend. “I’m used to working with women and gay men. We’re not in Kansas anymore.”

The Marpet clan has assimilated to their football life seamlessly. Joy recently had a breakthrough when she told Ali that she knew he had done something positive on Tom Brady’s quarterback sneak in the fourth quarter of their divisional round victory over the Saints. This, a few years after she was assured she didn’t have to worry when Ali wasn’t on the field—that just meant his team was on defense and Ali plays offense.

Ali, too, has broken free of the tidy “small school to the professionals” narrative. He laughs now at the burden of flying multiple flags proudly. He’s one of fewer than a dozen Division III players in the NFL. He’s one of the few Jewish players in the NFL. He’s one of a small handful of professional athletes representing the Finger Lakes region of New York. He has become an avatar for the underrepresented, despite the fact that he is more commonly associated inside the league as a player perpetually on the verge of Pro Bowl regularity.

Bill, in the way only he can, describes his son’s growth as a “time-lapse video of a flower blooming.”

Ali says one of the most meaningful parts of this journey was finding Bill in the stands after Tampa Bay’s win over the Packers at Lambeau Field. COVID-19 restrictions made it nearly impossible for in-person interactions, and Bill says the Buccaneers’ family seating was as far away from the field as possible to still have it be considered a stadium seat.

Bill wound his way toward the Buccaneers’ exit tunnel and when he and Ali saw each other they gave a thumbs-up and mouthed, “I love you.” Bill says the experience was otherworldly, almost as if Ali had surpassed him on the family totem poll in some kind of beautiful, ritualistic way. Here was another Marpet thriving, completely in love with their job and their life, a person who had grown immensely but also managed to stay the same, sure to slip on some kind of borrowed, team-issued sweatpants after the most significant moment of his life.

They were both nothing and everything alike, which made Bill feel their bond acutely in that moment. Nobody in his family, none of his kids, Ali’s mom, does anything halfway.

“I mean,” Bills says, “don’t we all want to have something we pass on to our kids?”