As COVID-19 threatens the college football season, what if we blew up the system entirely? Welcome to the Forde Bowl Subdivision.

Ten years ago this month, the last great spasm of realignment began shaking the college sports world. When it finally subsided in 2014, the landscape had changed dramatically. For the richer, but not necessarily for the better.

The Big Ten wound up with 14 teams, stretching from Nebraska to New Jersey. The Southeastern Conference expanded into Texas and Missouri. The Atlantic Coast Conference wandered nearly 1,000 miles inland. The Pac-12 annexed the Rocky Mountains. The Big 12, pushed to the brink of collapse, steadied itself by adding a school 1,200 miles to the northeast of the league office. Lesser conferences followed suit, scrambling for financial viability.

A decade later, it’s time to blow up what was done and start over. The COVID-19 pandemic’s effects have been profoundly felt in a realm where, for 10 years, money was no object and the map made no sense. Slapped in the face by a new fiscal reality, maybe we’re due to both rein in and reach out—to contract geographically into more regional conferences, while expanding the scope of the revenue gusher that is the College Football Playoff.

The radical realignment highlights:

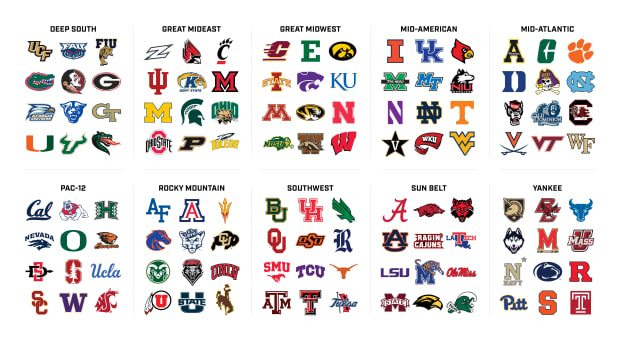

- A 120-school ecosystem, with 11 current FBS members relegated to FCS and one elevated from that level. Congratulations to North Dakota State; condolences to UTEP, Texas State, UTSA, South Alabama, Louisiana-Monroe, Bowling Green, New Mexico State, San Jose State, Coastal Carolina, Troy and Liberty. (Relegation/elevation can be revisited every three seasons.)

- Ten leagues, each with 12 members, each designed to maximize proximity and reduce travel demands and costs. All current conference structures are broken and reassembled. There are no more than eight Power 5 programs in a single new conference, and no fewer than four. And there are no independents—yes, Notre Dame is in a conference.

- In football, each school will play a full round-robin schedule plus one nonconference game (no FCS opponents). The nonconference opponent will be locked in for a minimum of four seasons before there is an opt-out to schedule someone different. There will be no conference championship games.

- All 10 conference champions, plus two at-large teams chosen by a selection committee, advance to the expanded College Football Playoff. The teams are seeded by the committee. The top four receive a first-round bye, while seeds 5–8 host seeds 9–12 at their home stadiums the first weekend of December. Quarterfinals are played the next week at the home stadiums of seeds 1–4. The semifinals and championship game are conducted under the current CFP format.

- There still will be bowl games for the teams that don’t make the CFP. Just fewer of them, which nobody should mind.

- The conferences will work for basketball and other sports as well—in fact, it will be better for nonrevenue sports in terms of travel cost savings. The 230-odd non-FBS programs that are part of NCAA Division I will remain aligned pretty much where they already are, with a few exceptions.

If only this could be pitched to centralized leadership of college football that was interested in the good of the entire enterprise. But that doesn’t exist, and that’s another column for another day.

What college football would gain from this realignment: uniformity; conference championships that truly matter; increased access to a more lucrative playoff; a more level playing field for the little guys; renewed regional identity; cherished rivalries preserved, restored—and, in some cases, forced into permanent existence. The advantages are abundant.

The complaints about conference schedules would disappear. Everyone would play 11 league games, taking on every opponent within the conference every season. There would be no unbalanced scheduling, beyond six home games vs. five, and that would be flipped every season. Without divisions, there is no luck of the draw in cross-divisional opponents. And the endless carping from conferences that play more league games than others would be silenced.

Having automatic playoff bids tied to conference championships—and having enough room in the playoff for every conference champion—would remove another chronic complaint. Win your league, get a shot at the national title. It’s just that simple. It works for the NCAA basketball tournament, and it would work for the new FBS.

And there would be triple the access to the playoff, from four to 12 teams. Instead of having to fight its way through eternal Big Ten roadblock Ohio State for a playoff bid, Penn State has a clearer path. Same with Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa and others. Schools out west would no longer have to worry whether their league was strong enough to compete for a playoff spot. Spreading around the heavyweight teams to more conferences increases playoff access, which should help with recruiting.

The alignment also would theoretically provide the have-nots of college football with a chance to stand toe-to-toe with the haves. League membership for the likes of Ohio alongside Ohio State, Georgia Southern alongside Georgia and Louisiana Tech alongside LSU is a step toward competitive equality. It might also include a lot of beatdowns—but at least they’d get to play the in-state powers that often refuse to schedule them, and every other year they’d get them at home. Those games would be huge for the host underdogs, from a monetary and prestige standpoint and for the chance at a memorable upset.

(If you’re concerned about a proliferation of mismatches in this conference alignment, you haven’t been paying attention. There already are plenty of blowouts on a weekly basis. Some 2019 numbers: 37 games involving SEC teams decided by 30 points or more; 36 involving ACC teams; 35 involving the Big Ten; 19 involving the Big 12; and 16 involving the Pac-12. Removing FCS opponents from the schedule will reduce the number of hide-your-eyes massacres.)

As for regional identity: This isn’t solely about making travel easier and safer for athletes and more affordable for athletic directors, although both factors are more significant now than at any time this century. It’s also an opportunity to rebuild a neighborhood with sensible boundaries that create common ground among people who already live and work together. There is not a lot of office or barber shop banter in, say, Orlando between Florida and Missouri fans when the Gators and Tigers play; there sure would be when the Gators play Central Florida. And the fans can pretty easily drive to many of these games.

Along those lines, think of the instant rivalries that would materialize: UCF and South Florida would get their shots at Florida, Florida State and Miami. Marshall would finally get West Virginia on an annual basis, and Cincinnati would get Ohio State. Fresno State, which has never played USC, UCLA or California at home and rarely played them anywhere, would meet them on a regular basis.

Then there are the rivalries torn asunder by realignment but put back together here: Texas–Texas A&M, Missouri-Kansas, Utah–Utah State. And how about these regular nonconference meetings: Oklahoma-Nebraska, Texas-Arkansas and Pittsburgh–West Virginia. Rivalries preserved by nonconference games: Alabama-Tennessee, USC–Notre Dame, Georgia-Auburn, Clemson–Florida State, Penn State–Ohio State, Nevada-UNLV. Dormant, across-the-river rivalries renewed via nonconference matchups: Louisville-Cincinnati, Kentucky-Indiana, Missouri-Illinois.

Now, the downside of the new FBS.

The flaws in this system are obvious. The consideration would have to be that the good outweighs the bad, and I believe it does.

This would require the fracturing of ancient conference bonds. Some Big Ten schools that had been aligned since the start of the 20th century would be splintered off into different leagues. Same with the rest of the Power 5—no conference would remain the same. Change isn’t easy, especially in college football. But they went ahead and broke the mold a decade ago, so this isn’t exactly sacrilege.

The biggest sticking point of the conference breakup is this: The Power 5 schools would have to share with the non-P5 schools, and that goes against every money-grubbing, power-consolidating principle they have come to espouse. When you have every advantage, giving some of them up is counterintuitive. The schools with clout would use that clout to stop it from happening. Staggering revenue shares based on competitive success is one option that could make the deal more palatable to the establishment schools.

(That list of schools would include Notre Dame. There’s no way the Fighting Irish will willingly give up independence to join a conference alongside Western Kentucky, Middle Tennessee and Marshall. But in this model, they have to go somewhere to maintain FBS membership. They are a better overall profile fit with the Mid-Atlantic or Yankee Conference, but for geography’s sake, they are where they are. At least they have Northwestern and Vanderbilt for academically elite, private-school company.)

The TV networks wouldn’t much like it, either. (For one thing, some of them would have to change their names.) There is a reason why so many Sun Belt and Mid-American Conference games are played midweek, and why other leagues are fighting for airtime on off-brand networks—those programs don’t do big ratings. So the idea of liberally sprinkling them in with the glam schools from the glam leagues, instead of keeping them in their corner of the FBS universe, would not be well received.

But let’s consider the possible implications of cord cutting, alternative broadcast platforms and a more diffuse media landscape. If there are more outlets, why not give them more conferences with headline acts? Why not 10 conferences that all have programs that are viable ratings draws, as opposed to five conferences with viewer appeal and five without?

There are academic incompatibilities that relate directly to the schools’ missions. There are athletic incompatibilities that relate directly to budget, scope and fan following. But what better incentive to improve than being able to play in the same leagues together—with the same access to the playoff? The biggest lament most schools in the Group of Five have is lack of regular opportunity to compete on the same level with the big boys. This plan presents exactly that opportunity.

Will it happen? Nah. But it’s fun to think about and argue about. The Great College Sports Realignment that began in 2010 can be improved upon, by simultaneously contracting and expanding.

Got a better idea? We'd love to hear it. Email your own proposed realignment to me at Pat.Forde@si.com. Your ideas could be used (with full credit) in a subsequent column.

Here’s the Forde Bowl Subdivision lineup (FBS Profile Rank is a 1–120 metric that combines a school’s five-year average Sagarin football ranking; its 2020 U.S. News & World Report National University ranking; and its 2018–19 Learfield Cup all-sports ranking):

THE PAC-12 CONFERENCE

THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN CONFERENCE

THE GREAT MIDWEST CONFERENCE

THE GREAT MIDEAST CONFERENCE

THE MID-AMERICAN CONFERENCE

THE SOUTHWEST CONFERENCE

THE MID-ATLANTIC CONFERENCE

THE DEEP SOUTH CONFERENCE

THE SUN BELT CONFERENCE

THE YANKEE CONFERENCE

RELEGATED

San Jose State

New Mexico State

UTEP

UTSA

Texas State

Louisiana-Monroe

Troy

Bowling Green

Coastal Carolina

South Alabama

Liberty

PROMOTED

North Dakota State