Jerry Dipoto says Seattle's latest rebuild is nearing completion. Should we believe him?

In November 2018, as Jerry Dipoto headed to a breakfast buffet one morning at the Omni La Costa resort in Carlsbad, Calif., he knew he needed a break. He did not expect one to materialize, like magic. This sentiment was based on several uncomfortable truths that had tied together in a knot he would need creativity or divine intervention to untangle.

The problems, deep into his fourth season as the Mariners general manager, were structural and compounding: the aging and expensive group of core players … the roster purposely built around them wasn’t good enough to overcome their drop-offs, injuries or suspensions … the barren farm system he inherited; barren, still … and the unlikelihood he could move any of the stars who were starting to grow old. Other than that? Everything was great!

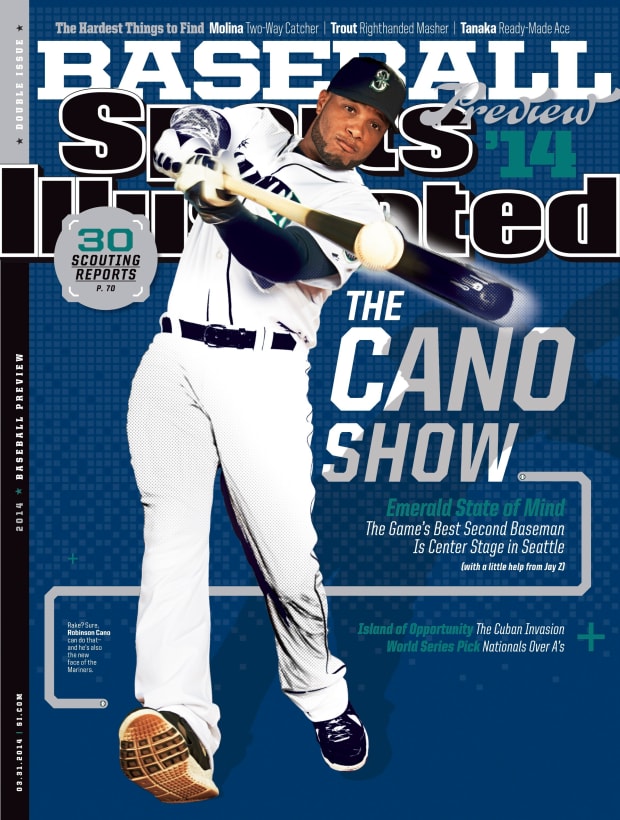

Dipoto cannot recall what he ate that morning, only who he sat next to and the seemingly innocuous question he tossed out. Who was Brodie Van Wagenen, the high-powered agent and new Mets general manager. Dipoto knew Van Wagenen well, since Van Wagenen represented Robinson Canó, one of the Mariners’ senescent stars, a high-priced and Hall of Fame–caliber middle infielder who was suspended for 80 games that season, after testing positive for performance-enhancing drugs.

After some small talk, Dipoto posed a Hail Mary query he believed he already knew the answer to. “Do you want a second baseman?”

“Maybe,” Van Wagenen said. Dipoto had worked through all the possible ways Van Wagenen would say no, expecting nearly anything except the answer he’d just heard.

On that morning, Seattle’s payroll floated high above sea level, at almost $158 million, with roughly 44% due to three players: ace Félix Hernández ($26.9 million, 32 years old), Canó ($24M, 35) and third baseman Kyle Seager ($19M, 30). “We were living on the edge with that roster,” Dipoto says, “and we knew it.” When their play didn’t match their pay, problems were inevitable. Because of their salaries, he couldn’t upgrade with high-profile additions. Because Seattle won enough—but not enough to make the playoffs—he couldn’t land coveted top picks. But now, he had been given a gift from the baseball gods; the moment every baseball team on the cusp of rebuilding dreams of had fallen right into his lap. Maybe.

Jennifer Buchanan/USA Today Sports

Dipoto floated back upstairs to his hotel room. Could the M’s really turn their biggest problem—Canó’s $240 million albatross—into the kind of elite pieces his farm system so desperately lacked? When he alerted top lieutenants to the “lifeline” now in play, one of them gasped. “Get the hell out of here” came next.

Negotiations commenced. Van Wagenen occupied a difficult position, as a new GM for a team in a major market that hardly ever engaged in any sort of overhaul. The Mets, despite their tortured history, played in New York. They needed stars. Needed to win now, always, especially when they weren’t winning. And Van Wagenen, who had never before worked in a front office, was hired precisely because he promised ownership that he wouldn’t go through the tank-and-rebuild process that so many other wayward franchises were doing with varying levels of success. More teams turned to this approach after the Cubs and Astros each famously endured long periods of losing in order to win World Series titles. Plus, surely no other executive in baseball valued Canó as much as Van Wagenen did.

The Mets pushed for the inclusion of closer Edwin Díaz as the deal’s centerpiece, with Canó—and his paychecks—thrown in. Even though Díaz was popular and could sling fastballs around 100 miles per hour, Dipoto didn’t mind because that structure emboldened him to ask for more in return. For a one-inning closer and an aging former star player he was ready to move on from, Dipoto managed to turn one breakfast into two pillars for the rebuild he knew, deep down, he needed to embark on. A fortunate team that desires an extreme makeover would seek either future talent in exchange for its best players or financial assistance that would allow for flexibility in long-term maneuvering. The Mariners managed to snag both, dumping the contract and receiving outfielder Jarred Kelenic, who would soon develop into a top-five prospect.

On the morning of the trade, the fortunes of a perpetually middling franchise changed, pointing the Mariners toward either the postseason or a new regime. Regardless, Dipoto had cajoled and bamboozled his way into the best possible scenario to start a rebuild—the first step in not just ending the longest playoff drought in professional sports but perhaps vaulting Seattle to its first World Series title. He had leapt five steps or more beyond any sober expectation, but he knew that many would not see the shift that way, especially in Seattle.

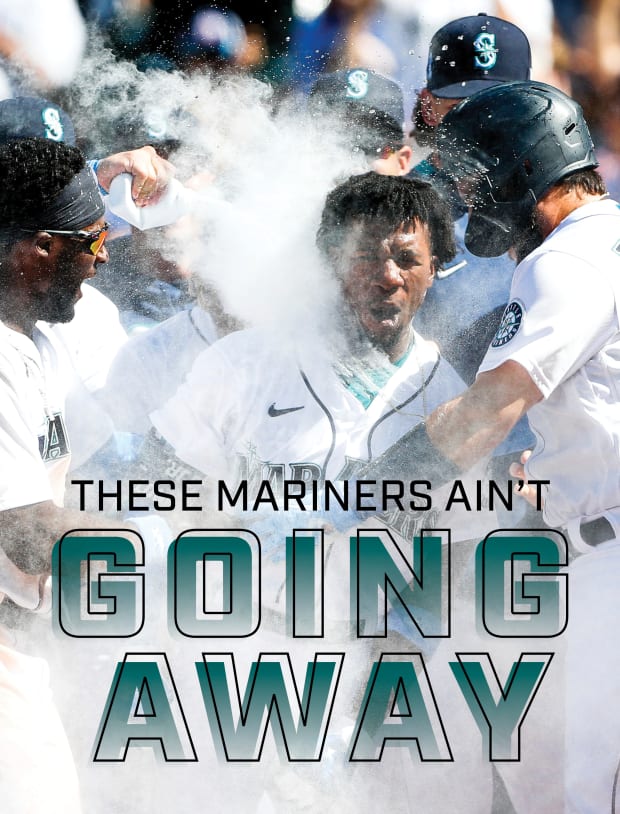

Now, as the 2021 baseball calendar winds toward the postseason, the overhauled Mariners are far better than expected, teeming with earned optimism—and in need of a miracle to reach the playoffs. They entered Tuesday three games back of the final American League wild-card spot, with 13 left to play and three teams ahead of them. But to Dipoto, this was all part of the plan.

Joe Nicholson/USA TODAY Sports

I thought the Mariners were building toward that commissioner’s trophy in 2008 and ’10 and ’13 and ’19. Now, current me would like to ask past me: what in the name of The Process were you thinking?

Then, the story idea landed in my inbox a few months back: could we write about the Mariners’ latest overhaul? On instinct, I cringed. Not because I wasn’t interested, but because I had taken that approach an embarrassing number of times before. As the longest playoff drought in professional sports grew longer, I wrote about Seattle’s baseball team in The Seattle Times, The New York Times and Sports Illustrated. But these pieces started to resemble a Mad Libs exercise. Just change the names and adjectives.

I can trace my career through the baseball team I followed growing up and our brief but perpetually intersecting history. Watching Ken Griffey Jr. slide into home in the 1995 playoffs made me want to write about sports, to capture moments and uncover meanings.

While interning at The Buffalo News in ’01, I often stayed late to input one of the Mariners’ record 116 wins into the agate section, remaining in tune to their magic. In ’05, I covered Hernández's first major league start. In ’07, I wrote my last piece before moving to New York from Safeco Field—on, of course, a September night where the Mariners were mathematically eliminated from playoff contention. In ’08, I even went to Sir Mix-a-Lot for answers. He also had none, suggesting “purgatory” as the title of a song he might write about the downtrodden Seattle sports scene.

I continued to buy bridges that weren’t for sale: former general manager Jack Zduriencik’s scheme to win with defense (NYT, 2010), the impact of an ace like Hernández’s remaining in Seattle (NYT, ’13), Jack Z’s splashy Canó signing (SI, ’14, my first cover).

Robert Beck/Sports Illustrated

The drought that continues speaks to the flaws in those pieces. Hernández did not down Fireball whiskey at a victory parade like Marshawn Lynch of the Seahawks, despite King Félix telling me he planned to. Canó did not save baseball in Seattle. Zduriencik did not return the Mariners to the postseason, same as the two executives who preceded him.

Dipoto took over in 2015, inheriting that existing—but expensive—core. Of course I wrote about him, too (SI, 2018). I wish someone had stopped me. I wish I had stopped myself. That ’18 story focused on the franchise’s “holistic” approach to baseball operations, the use of advanced technology, soft-tissue massage therapists, staff chiropractors and specialized position coaches. When we published, Seattle remained in playoff contention—but, as always, not for too long.

What I didn’t realize when my editor pitched another rebuild story only became clear in Dipoto’s office after I told him I wanted to write about all that I had written about before. Plus why, now, this time, things were different. My key mistake in all the older pieces—beyond the flowery over-writing and the wholesale buy-ins—was that I had written several things under the same umbrella without truly understanding rebuilding as a concept.

Where writers and analysts tend to view teams in binary terms—as contending, or rebuilding—general managers like Dipoto must live in a continuous, nonbinary cycle. When someone asks Dipoto if he’s “all-in,” his response is “Always. Just depends what we’re all in on.”

Sitting in that office in early July, nearby the books on leadership, with the amateur draft fast approaching, Dipoto gently took issue with my body of Mariners-related work. He saw only one instance where the Mariners had truly been “rebuilding”—the actual extreme makeover that started one morning in Carlsbad.

Stephen Brashear/Getty Images

To enhance the Mariners’ forever-middling playoff chances, the organization first needed to change its culture. That process began when Dipoto hired Andy McKay, a peak-performance specialist whom Dipoto had never met. The GM recruited McKay for his brain and his brainstorm sessions, which often led to fresh, innovative ideas. All centered on the same place: development, and not just for players.

Much progress has been accomplished there, from book clubs to “Dare to Suck” meetings to camps where pitchers add velocity. McKay wanted the Mariners to be open-minded, creative, communicative, focused on growth, free of boxes to be checked and inflexible ideas of how baseball should be played or how players should be trained. “We started trying different things that in [all my] years of baseball experience, I would never have even considered,” Dipoto says.

McKay desired to lead his industry in transparency, the ugly truths and inevitable pitfalls laid bare rather than ignored, bubbling beneath the surface. He wanted to build trust through vulnerability, his focus less on a new roster and more on a new frontier. The Mariners wanted to win, he says. “But focusing on actually winning, I can’t control that. Nobody can.”

He laughs. “I hope you print that because it will piss everybody off,” he continues. “But it’s the truth. If somebody could actually control winning they would have done it by now.”

McKay encouraged employees across the organization to create demos and present them. He made no rules and set no limitations. He wanted weird, bold. Someone suggested an internal website, with the team’s new direction spelled out and all tools available to everyone, like advanced analytics that players could read, interpret and utilize to tweak their workouts. Or book recommendations. Or team rules and why they mattered.

And yet, the Mariners remain a cultural work in progress, their aims not yet fully realized. In some quarters, particularly from the viewpoint of rival clubs, Seattle has given baseball—and its fanbase—reason to doubt the sincerity of its approach.

For that, the Mariners can shake their collective head at former president and CEO Kevin Mather, who “resigned” in February, the word choice a formality, a palatable way to say “fired, immediately.” Mather’s departure followed the release of footage from a Zoom call of a speech he gave to the Bellevue Breakfast Rotary Club earlier that month.

His comments went far beyond acceptable, or even understandable, bounds. Mather denigrated Japanese hurler Hisashi Iwakuma and outfield prospect Julio Rodríguez for how they spoke English; called Seager “overpaid;” harkened back to when the team could send a Latin American prospect to "a dumpy old academy with no hot water and a lousy rock-filled field"; spilled private contract details; and admitted, incredibly, in public, to service-time manipulation. For an organization that said it would love the people that donned its jerseys, those words, from a high-profile employee whose tenure began in 1996, sounded like a peek into the “real” thought process of team brass. (Mather, in a statement, took full responsibility for the vileness that had spewed forth.)

Still, rival executives continued to paint Seattle as an organization sometimes at odds with its own players—an antithetical counter to its desired ethos. A portion of the clubhouse fueled that sentiment at the end of July, as players voiced their displeasure to The Seattle Times the Monday before the trade deadline. Dipoto had traded relievers Kendall Graveman and Rafael Montero for infielder Abraham Toro (24, contract under club control) and reliever Joe Smith (adding, also, starting pitcher Tyler Anderson and closer Diego Castillo before the Friday trade deadline).

“They don’t care about winning,” one player told the newspaper.

Dipoto clarified those events in two interviews with SI, saying he believed that players should express themselves, that he wasn’t surprised when they did and that he was proud of them for speaking out. Skeptics might roll their eyes, but it’s his perspective, nonetheless, same as his belief that Mather’s dismissal galvanized the clubhouse. Dipoto insists that he “always” considers chemistry. But in his view, the moves upgraded his team at multiple positions, signaling how much the Mariners do care about winning.

Still, that sequence, from the embarrassing speech to the players publicly saying they felt betrayed, cast doubt on the rebuild. For all of the change, Dipoto has not yet ramped up the team’s spending, which would kick his plan into overdrive. And yet, people in baseball, even those who wish the Mariners a century of regular-season failure, look at what’s in place … and are jealous as hell.

Jennifer Buchanan/USA TODAY Sports

Why? Because of elite young talent like Kelenic and Rodríguez (second in MLB.com Pipeline’s latest prospect rankings). Because of elite young arms like Logan Gilbert (starter, first round, ’18, already in Seattle), George Kirby (starter, first round, ’19) and Emerson Hancock (starter, first round, ’20). Because the barren system that Dipoto inherited is suddenly bursting with talent. Because of Mitch Haniger (30 years old, right fielder, career-high 34 home runs), J.P. Crawford (26, Gold Glove shortstop) and Kyle Lewis (26, outfielder, rehabbing from knee surgery, last season’s American League Rookie of the Year).

That’s exactly where Dipoto starts to make the case that this plan is truly different. Not trying something new but a full rebuild. (Will I regret typing that five years from now? Perhaps.)

In this reboot, the Mariners changed the way they evaluated prospects, reducing their total number of amateur scouts, dropping from a total of 70 to closer to 30 now (though the 40 employees let go would likely disagree that such cuts were needed). They replaced those eliminated positions with video and quantitative analysts, building out a draft model that didn’t exist 10 years ago, removing as much subjectivity as possible in favor of data-driven comparisons. The model grew more and more specific, until they rated things like a college catcher’s projected ability in A ball to “receive” the pitch and “steal” strikes.

Seattle hired pitching and hitting strategists. It looked at existing skill sets and attempted to amplify strengths, even unusual ones. It focused less on repetitions—more swings, ground balls, bullpen sessions—and invited more guest speakers, non-baseball types with fresh ideas that injected “energy and synergy,” a favorite Dipoto phrase.

To understand how Seattle arrived there, Dipoto must travel back to 2015, when he warned the ownership group about its talented but not sustainable roster. Seattle ranked among the oldest teams in the American League.

Those teams were always good, never great: from 2015 to ’18, Seattle amassed the fifth-best record in the AL, where five teams now make the playoffs every season. The Mariners did not, while eight other AL franchises did. “I won’t even say we were particularly close,” Dipoto says. He’d like to blame the expanding run of no postseason baseball on bad luck. But, “for the most part,” he says, “that’s probably just bad timing.”

Sensing impending doom, Dipoto sought to add complementary pieces who could contribute right away, alongside the stars. But for every deal he put together, he insisted on at least one “controllable player,” then looked for pieces that fit his narrow, cash-strapped criteria, landing Haniger and starter Marco Gonzales in ’17.

A year later, MLB handed down the Canó suspension, and the clubhouse culture struck Dipoto as “wonky,” after the second baseman did return. Cautious optimism now bent more toward delusion. Dipoto remembers a “lot of angst,” as players divided into cliques. Season lost, he dealt starter James Paxton and catcher Mike Zunino.

Only the Díaz deal—and the attendant shedding of a progress-preventing contract—dramatically changed the calculus. Only then could Dipoto shift everything, including course; fix the payroll (now roughly $87 million); collect young talent; and embark on what ace broadcaster Shannon Drayer termed a “step back” in a question posed to Dipoto after the blockbuster trade. Dipoto agreed with the phrasing. But in this “step back,” he saw the ability to take many steps forward—right away and in future seasons.

Alika Jenner/Getty Images

The skeptics did not exist only in the stands at what’s now called T-Mobile Park. The ownership group clung to its own doubts, and before Dipoto could put his grand, career-altering (one way or another) plan into action, he needed to convince them that, this time, he was right.

In August 2018, Dipoto stood in a room filled with the only people he truly needed to sway. He looked at Mather; John Stanton, chairman and managing partner; and Chris Larson, minority owner; and told them, with conviction, that they needed to … get rid of their best players.

The Mariners would win 89 games that season, while drawing 2.29 million fans to their ballpark, the most since ’08. But where decision makers removed from daily operations saw progress, momentum, the general manager instead pointed out a mirage.

The faces that stared back at him, from the men who expected him to make Seattle a baseball town again, who had signed him to a multi-year contract extension only a month earlier, all begged the same question. Are you crazy?

Dipoto pressed forward, with slides and data and the speech of his baseball life. After a few hours, he managed to gain a solid answer. Not a “yes.” A “let’s keep talking.”

They met again. Then met again. At the end of their third meeting on the future of the Seattle Mariners, the brass told him, “This is what we hired you to do.”

Before then, Dipoto says, “I’m not sure that a ‘rebuild’ ever happened. We’ve always walked to the water’s edge but never jumped in the pool.”

He began gathering his front office for “whiteboard moments,” a practice he borrowed from Steve Jobs. As they scribbled out potential trades and evaluated prospects, they zoomed out, toward 2026. They drafted mostly college players, who were closer to the big leagues, in order to “populate our system.” The transformation had officially begun.

None of Dipoto’s bosses wanted to “step back” into being a bad team again. But that happened in ’19—and, in large part, by design. Dipoto hated the phrase most commonly used to describe his new plan—tanking—calling it the “most overused in baseball.” Like McKay, he adds a defense, unprompted. “We really do care about winning.”

Dipoto simultaneously lowered payroll and collected prospects, transforming his farm teams and his major league one. With the stars departed, players like Haniger and Gonzales had more opportunities to flourish. Players like starter Justus Sheffield and Crawford had chances to develop as regular major leaguers, which likely wouldn’t have happened had Seattle not acquired them.

The optics remained poor, if not unexpected, a point made clear to Dipoto on one elevator ride at his home stadium. While he headed back upstairs to his office after one event in late ’18, an attendant, an older woman, looked at him and started to cry.

“Are you O.K.?” he asked.

“I’m angry with you,” she said.

When he asked why, she blurted out, “Because you traded all of our players.”

“We’re trying to get better,” Dipoto said. “We think this is the fastest road to winning a World Series.”

“You may think that,” she responded. “But you traded all my favorites, and I don’t have much time.”

Dipoto wanted to explain. He hated that so many losing seasons combined to worsen the lives of people who cared about his baseball team. But, he also didn’t believe that his front office could be held responsible for injuries, bad luck, worse decisions, terrible trades, or unwieldy contracts finalized before his hire.

On that day, he rode the rest of the way up in silence. After all, he saw her point.

Steph Chambers/Getty Images

The Mariners entered September flawed, exciting and still in the playoff mix. Seattle is not the 70-win team it was projected to be (the Mariners reached that total on Aug. 29). And they certainly won’t be in future seasons. “We feel like the next five decades of Mariners baseball looks brighter than, really, it has looked in decades,” Dipoto says.

He shakes his head. “I have never had more fun working in baseball since we started this, since we dove in,” he says.

Still, the obvious question lingers: can fun and youth and a people-focused approach to baseball yield the one thing that has escaped the Mariners for two decades: that ever-elusive playoff berth? There’s no question that Seattle’s baseball team is ahead of schedule and primed for the future. Dipoto believes that other teams across baseball have “taken note of some of the things we’re doing.” McKay says that the best example of the benefits to this open, inventive approach is “the Mariners right now.” Manager Scott Servais has described his club as having a fun differential of +90, prompting either more eyerolls, laughter at the joking comparison to their run differential or a deep belief in their unusual victory style.

Skeptics who have earned their doubts often point to Seattle's run differential (–60 entering Tuesday) and its record in one-run games (31–18). Dipoto argues that those are both products of the unpredictability of younger, still-growing players. “Our magic sauce,” he says, “the one-run wins.” Only now, whether through luck or youth or some combination of both mixed with kismet, Dipoto believes the soul of his club “portends to something greater.”

Their slew of close wins recalls the days of Sodo Mojo. The four game-winning grand slams speak to the hubris of young talent. The bullpen, stocked mostly with non-roster invitees and developed arms, continues to pitch above expectation. This is the plan, in action. But try telling that to the elevator operator.

I remember other buzzwords, strategies, anecdotes—the stuff that birthed similar excitement boosts. Reality, as always, is complicated. Lewis has faced rehabilitation setbacks; Kelenic, a season-long slump; Gilbert, a late-season lull. The M’s have pivoted from what’s called “eye wash”—extra reps, old-fashioned training—but reasonable baseball minds wonder if book clubs, batting specialists and creative meetings are just same concept, new version.

Will it work? If you made it this far, you know you’re clearly asking the wrong person.

Here I am, two decades later, a writer who is embarrassed by his body of work on one rebuilding baseball team. One of my best friends is ESPN’s Jeff Passan, and he has still never been to the Mariners ballpark, because they have been mediocre for both decades of his baseball writing career. As I started to buy into Dipoto’s case for this makeover being different—envisioning my Ben Reiter moment, after he tabbed the Astros as future champions years before they won a title—Passan laughed, estimating that the Mariners have a 5% chance to make the postseason this year. Entering Tuesday, their actual playoff odds are even less hopeful than Passan was a few weeks ago: Baseball-Reference gives them a 1.7% chance to make the postseason; FanGraphs, 1.4%.

That won’t dampen Dipoto’s enthusiasm, nor McKay’s aims. By mid-August, the Mariners were 10 games over .500. They've carried their playoff hopes deep into September. Their record vaguely recalls the overachieving of ’18, only now, they’ve got the farm talent to complement Haniger, Crawford and Ty France—and all the other “controllable” big leaguers acquired when Dipoto began his overhaul. Baseball America places Seattle atop its farm system rankings. Passan believes the M’s will end the drought in three to five years. Although, after 20-plus years of Passanisms—what we call his consistently wrong predictions—I’m wary of his take, too.

The ownership group no longer sits among the skeptics. In September, they handed Dipoto another “multi-year extension” and promoted him to president of baseball operations. They also gave Servais, a longtime Dipoto confidant, an extension of his own.

Dipoto sees his plan materializing and knows that, even with his new deal, he’s unlikely to shape another one. The point wasn’t to play in one wild-card game this season. Instead, Dipoto chooses to look toward the future, yet again, and he hopes that the elevator operator will do the same.

That’s the thing about rebuilding, though: the beauty in any one plan versus another lies with the person who holds the hammer and begins tearing down the walls. Eventually, plans must yield wins, division titles, playoff berths. Even a World Series title. One man’s tank job is another man’s treasure. And a writer who can’t seem to stop writing about rebuilding may buy Dipoto’s case for differentiation—only to become a sucker once more.

More MLB Coverage:

• There Is Only One Choice for AL MVP

• The Ohtani Rules

• Salvador Perez's Career Year Bucks Trend for Aging Catchers