Horrid discoveries have forced a humbling conversation about the sport's role in “cultural genocide” against Indigenous peoples.

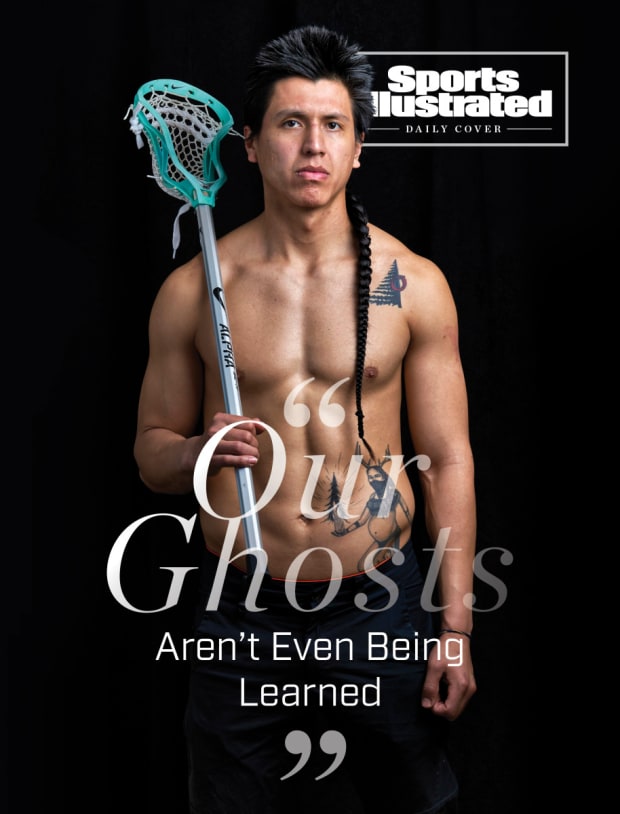

On June 12, in the second week of the Premier Lacrosse League season, one of the greatest players of the game’s modern era darted around Fifth Third Bank Stadium in Atlanta, just as he has done so often across his seven-year career. Cannons attackman Lyle Thompson fired home four goals, all from a variety of angles, on a PLL-season-high 14 shots—and while, yes, the Whipsnakes threw everything they had at him on defense, Thompson found himself weighed down less that afternoon by the body checks and poke checks than he was by the orange ribbon weaved through the bottom of his long, black braid. And by all that it represented.

Thompson, a member of the Onondaga Nation, took the field in Atlanta grieving 200-plus Indigenous children whose unmarked graves had been discovered a month earlier at the site of what was once the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia. By wearing the ribbon he aimed to channel his sporting spirit toward those who’d gone without a proper burial, and who’d never been acknowledged. And that energy, he says, “played a toll on my body. It played a toll on my mind.”

Kevin D. Liles/Sports Illustrated

Canada’s so-called residential schools first opened in the late 19th century, and as recently as the late 1990s they remained a place where Indigenous youths—more than 150,000 of them, some as young as 3—were taken to be culturally indoctrinated. So far, 139 such institutions have been identified, the majority of them run by the Catholic Church, and there Indigenous children were systematically stripped of their Native culture, language and spirit.

In 2015, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Committee produced a report alleging that children in those schools faced sexual, physical and emotional abuse and violence. They lived in unsanitary, cramped quarters and were often underfed. At least 4,100 students died, the committee estimated—but that number is likely higher given the spotty record keeping of the time. This summer alone, Indigenous nations released reports of some 1,300 unmarked graves found across the country, at Kamloops and at three other sites—and these recent findings have sparked an intense response, as an increased awareness of Canada’s often-exploitive past has forced a reckoning. (The United States is not innocent of such mass mistreatment, having opened 350-plus similar boarding schools, operated with a similar purpose.)

For Thompson, and other allies across the PLL, that reckoning is focused largely on the ways in which their sport was leveraged in what the committee called “cultural genocide.” Lacrosse, a game invented some 1,000 years ago by Native peoples, became an assimilative tool used at residential schools—“which is extraordinary,” says Allan Downey, an associate professor at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, and the author of The Creator’s Game, which explores Indigenous identify formation as it relates to the sport. “They [used] an Indigenous element—an Indigenous game that has deep connections to the epistemologies of Indigenous peoples—and they [used] it to assimilate Indigenous youth.”

Throughout the PLL season, to draw awareness to the subject and inspire education, Thompson and other players wore—and the league sold—orange helmet chinstraps, with proceeds going to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. Indigenous players emphasize that acknowledging lacrosse’s origins is key to the future of a game that today is widely perceived as white and upper-middle-class. “Our ancestors, they deserve the recognition,” says Zed Williams, who grew up on the Cattaraugus Reservation, just south of Buffalo, and who will lead the Whipsnakes into the PLL championship game against the Chaos this Sunday. “They deserve the voice they never had.”

“Right now,” says Thompson, “our ghosts—our ancestors—aren’t even being learned.”

John McCreary/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

Just more than a century ago, Canada’s deputy minister of Indian affairs, Duncan Campbell Scott, spelled out to a parliamentary committee the intentions behind an amendment to the nation’s Indian Act—a bill that itself determined the legal status of Indigenous peoples. “Our object,” he said, “is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic.”

That bit of Canadian legislation marked the latest in a decades-long string of restrictive measures used by the government to strengthen its control over an Indigenous population that at the time numbered more than 113,000. Often, upon arriving at a residential school, Indigenous students were assigned new names. Native languages were suppressed, as were cultural and spiritual practices. Even recreation was viewed as an instrument for assimilation, as games like cricket and baseball, lacrosse and ice hockey were taught in hopes of “ ‘civilizing’ residential school students,” the Truth and Reconciliation Committee reported in 2015. Another investigation, the Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal People, observed of sport’s role in it all: “Recreation was re-creation.”

What stands out about lacrosse here—what makes its weaponizing especially devious—is its preexisting place in the Indigenous population. The Haudenosaunee, for one, have long considered the game a gift from the Creator. In various Indigenous populations it is incorporated into religious ceremonies and used to teach ideals of respect and peace. Some ascribe the sport healing powers, referring to it as a medicine game.

In its original form, lacrosse was played with a wide number of rule sets, which could be laid out before any given contest, but the simple concept of joy was central to its creation. “Where it originated from—and where the heart and soul of lacrosse is—is on reservations,” says Williams. “These people live for lacrosse. They’re so passionate about it.”

But the style of lacrosse commonly seen today looks vastly different from what was conceived by Native peoples. Toward the end of the 19th century, a Montreal dentist named William George Beers codified a version of the sport that much more closely reflects today’s game. Beers, who as a teenager competed recreationally, standardized the use of a rubber ball, the length of a field and the size of a goal. In 1979, more than 100 years after he published a pamphlet outlining a number of the game’s basic procedures, he was posthumously inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame. For his efforts, Beers is traditionally regarded as the “Father of Modern Lacrosse.”

But Beers, Downey says, should instead be known as the “architect of the colonization of the game.” Downey, who is Dakelh, Nak’azdli Whut’en, and who was drafted by the National Lacrosse League’s Arizona Sting in 2007, deems Beers responsible for lacrosse’s role in residential schools “because he’s the one that created this rhetoric that it was Canada’s national sport”—and that it was “white, civilized enough and masculine enough to be used in the assimilation of Indigenous youths.”

Beers’s framework redefined lacrosse in a Westernized manner, with little to no spiritual value. There was variety to the way the game was played across Indigenous nations, but lacrosse taught at residential schools stuck rigidly to the structures Beers mapped out.

“You assimilate the game, and the byproduct of that is you’re assimilating the people who made it,” says Frank Brown, who was raised on the Allegany Reservation, and who played for the Whipsnakes at their training camp this spring. That assimilation was put on display on the occasions that residential schools were pitted against non-Indigenous teams from public institutions. These games, Downey points out, were set up to demonstrate “how much progress [school administrators] had made in the civility cause they were undertaking—as a way to showcase [Indigenous students] in this kind of ethnographic zoo, as if they were on display for the public to see.”

As culture is stripped away, identity loss can take any number of forms. Williams, the Whipsnakes star, was raised outside of Buffalo by a father, Daniel, who attended the Thomas Indian School, a boarding school that operated on the Cattaraugus Reservation between 1875 and 1957. Later, on the reservation, Daniel’s parents both became pastors, running a Christian church. Williams never talked in depth with his father about the school, or about his father’s childhood, but Williams believes he had mixed feelings about his Indigenous heritage. “Some days he would be really traditional in Native ways; some days, not so much,” Williams says of his father, who died in 2017. The Thomas Indian School, he says, “definitely [was] a big factor in how our dad raised us.”

That meant: Zed and five of his six siblings were named after figures from the Christian Bible. At meals, they prayed in English, not in their ancestors’ language of Seneca. And as Williams gravitated toward lacrosse throughout his youth, he did so largely uninformed of the game’s spiritual associations. His father never played the game; he took instead to football and wrestling. When Zed learned the game, winning was prioritized over anything else—in conflict, broadly, with Indigenous values.

As Williams has aged, though, he has come to better understand “the medicine and power that lacrosse has,” in large part through conversations with Indigenous teammates. Still, he says, “so much was erased and forgotten. ... I’m still learning.”

Courtesy of Premier Lacrosse League

Thompson, the Cannons star, grew up on the Onondaga Reservation outside of Syracuse, always feeling a kinship with his lacrosse stick. As a child, he shared a twin-sized mattress with an older brother—and still made room for his stick in bed every night. He’d take it to the grocery store, to the laundromat …

Unlike Williams’s father, Thompson’s dad, Jerome—who didn’t attend a residential or boarding school himself—made sure that his five children understood the cultural and spiritual implications of the medicine game. “[My father] taught me how to respect my stick, care for my stick, treat my stick nice,” Thompson says, “and know that you get something in return for that respect.”

Indigenous players such as Thompson see it as paramount to their sport’s future that these roots and cultural origins are recognized, especially as lacrosse grows globally. In July, the International Olympic Committee endorsed full recognition of the game, a decision seen across the lacrosse community as a precursor, potentially, for upcoming Olympic inclusion. And an indicator of its popularity. At the same time, Thompson sees a pastime in which the vast majority of players are white—83% across both sexes, in all collegiate divisions, according to the NCAA.

Lacrosse is “a part of our culture and a part of our history,” says Randy Staats, an attackman for the Chrome who grew up on the Six Nations Reservation in Ontario. “To leave that unknown is completely wrong. People [must] know where this game comes from. … It’s in our ceremonies; it’s in our teachings.”

With that in mind, Staats started a nonprofit last September built around clinics for Indigenous and non-Indigenous children, teaching the game’s fundamentals and history. But he’s looking to start broader conversations in his professional realm as well. On June 6, two weeks after the discovery of the unmarked graves at Kamloops, Staats walked into Gillette Stadium for the PLL’s opening weekend wearing an orange T-shirt with “EVERY CHILD MATTERS” plastered across the front. Staats had torn his ACL in training camp earlier in the spring, but he still had a platform, and he used it that afternoon to “get somebody to ask a question.”

Kamloops was the first of several similar findings across Canada that was shared this summer. In July, after 160 more unmarked graves were located at the site of the former Kuper Island Indian Industrial School, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was compelled to speak, saying his “heart breaks” for those impacted. And by mid-August, the Canadian government had announced it would commit some $320 million toward searching for more grave sites and providing mental support for Indigenous survivors still recovering from the trauma.

Geoff Robins/AFP/Getty Images

Staats, with multiple relatives who attended residential schools, hopes that both the Canadian and U.S. governments take further ownership of that trauma by ensuring residential schools and their effects are more directly addressed in history books. Players like Thompson, meanwhile, have done their best, too, to make sure the story stays front and center.

On the day he first weaved an orange ribbon into his braid, the Cannons attackman was so committed to sending energy to those who’d died that he says he overexerted himself, sustaining a Grade-2 pull in his right groin. He wore the ribbon for three more games, each outing further straining himself physically and mentally. And while the pain in his groin subsided by season’s end, the hurt from decades of mistreatment—“the untold truths”—lingers, he says.

“I want there to be healing,” he says. “But the healing doesn’t happen until the United States and Canada acknowledge this part of their history, whether that history hurts or not. It has to be told.”

• The 9/11 Story That Inspired Tom Brady

• Colin Kaepernick Went First. They Were Second

• Dak Prescott’s Heal Turn