The U.S.'s semifinal opponent has built toward hosting the 2022 World Cup by becoming the Asian champion, and its relationship with this region is only just beginning.

Guests are traditionally honored and indulged in Arab culture, and at this month’s Concacaf Gold Cup, the Qatari national team hasn’t hesitated to make itself at home. Competing as an invitee to the biennial regional championship, the Maroon have been playing like they own the place, storming into the semifinals with a 3-0-1 record and a tournament-high 12 goals.

Qatar has added a bit of mystery and intrigue to an event that many of the continent’s best players are missing because of injury, timing and coaches with competing priorities. But now it’s threatening to overstay its welcome. A victory over the U.S. Thursday night in Austin would earn the Qataris a berth in the Gold Cup final, leaving the confederation just 90 minutes from confronting the awkward possibility that the champion of North and Central America and the Caribbean could hail from the Arabian peninsula.

Already the kings of Asia, Qatar, which has never qualified for a World Cup and is ranked just 58th by FIFA, would become the first country to hold two continental titles simultaneously (Australia, which moved from Oceania to Asia, won those respective crowns 11 years apart). Seeing the Maroon lift the Gold Cup in Las Vegas would be slightly embarrassing for Concacaf, but it would be easily explained: The usual championship suspects are well below full strength, and Qatar is a complete, skillful and cohesive side.

But even if Qatar falls to the U.S. in Austin, or to Mexico or Canada on Aug. 1, that won’t be the last we see of them. Qatar is going to become a much more familiar face in Concacaf—a guest with its own house key. This wealthy and ambitious (and some would say amoral) country, which is smaller than Connecticut, has become a fixture on the global sports landscape. And soccer has become a primary lever in its pursuit of influence and legitimacy. Qatar is hosting the 2022 World Cup. It was the site of the 2011 Asian Cup and the FIFA Club World Cup in 2019 and last February. It owns Paris Saint-Germain. The country’s most ubiquitous brand, Qatar Airways, is a World Cup and European Championship sponsor, and its logo appears on jerseys worn by AS Roma, Boca Juniors, Bayern Munich and more.

In addition, its national team, once an afterthought, is now a trophy-winning ambassador unrestrained by traditional bureaucratic boundaries. Qatar played in the 2019 Copa América, and it was scheduled to take part in this summer’s before withdrawing because of scheduling issues. It was invited by UEFA to complete a five-team 2022 World Cup qualifying group by contesting friendlies against the odd team out on each match day. And now it’s playing in the Gold Cup. Money paves the way, and unique competitive opportunities follow. Qatar will spare no expense to field a team worthy of the World Cup.

Concacaf’s relationship with Qatar began in 2018, when it signed a cooperation agreement with the Asian Football Confederation. Those sorts of deals are common, and they often include elements touching on administration, development, refereeing and best practices. The following year, Qatar won the Asian Cup for the first time and as the next World Cup host, it became the confederation’s flagship. Considering Qatar’s ascendency, communication with Concacaf was a natural outgrowth and last year, an invitation to the 2021 and 2023 Gold Cups was announced (the next Asian Cup also is in the summer of ’23, so something will have to give there).

Qatar would be the Gold Cup’s first guest entrant since 2005. At that time, Concacaf wanted to send the message that the confederation was deep enough to stage a compelling and competitive tournament on its own, without the need for big-name guests from South America or elsewhere. Concacaf was growing. Fifteen years later, it decided that it can grow even further with Qatar’s help.

Last week in downtown Houston, Concacaf president Victor Montagliani, Concacaf director of development Jason Roberts and Qatar FA general secretary Mansoor Al-Ansari unveiled an initiative that will see Qatar fund grassroots coaching recruitment and education programs in each of the confederation’s 41 countries over the next four years. Concacaf didn’t provide a dollar amount, but Qatar’s investment is significant—potentially vital in some places—and emblematic of how the country uses sports, and its largesse, to acquire influence and opportunity abroad.

Montagliani said the program would “give a tremendous boost to grassroots and community football in Concacaf.” When extending the Gold Cup invite to Qatar last year, Montagliani claimed the relationship “will be game-changing for the development of football at all levels in our region.” It also would open lines of communication and cooperation between the next two World Cup hosts.

The financial ties between the parties were strengthened further this month, when Qatar Airways was unveiled as a sponsor of both the Gold Cup and Nations League. Its logo has been all over the stadiums and Fox broadcasts, and its name will be attached to the official Nations League brand when the region’s secondary men’s national team event restarts in 2022. The money will help support the travel required for many of Concacaf’s smaller countries. In exchange, the airline gets to introduce itself to the American and Mexican fans expected to travel to next year’s World Cup. It’s all part of the country’s master marketing plan.

In most ways, this is modern sports. It’s a business. But Qatar isn’t like most marketers. The country is the product, and it’s a country that has faced sustained and warranted criticism for its human rights record and the kafala system that supports the construction of the 2022 World Cup stadiums. The regulations governing migrant labor in Qatar restrict workers’ rights and freedom of movement, produce unsafe conditions and can be economically exploitative. In February, The Guardian reported that more than 6,500 migrant laborers from five South Asian nations have died working in Qatar since the World Cup hosting rights were awarded in late 2010.

The world continues to work with Qatar, however, and tie-ups and cooperation with its government and sporting institutions have been normalized. Asked to comment on its relationship with Qatar, Concacaf referenced the aforementioned exchanges and investment in the region and said in a statement provided to Sports Illustrated, “While we understand and acknowledge that there are sometimes questions raised about wider political and social issues, we believe in positive engagement, in developing football regardless of wider politics and in using the sport as a force for good within Concacaf and beyond.”

Speaking to reporters Wednesday afternoon, U.S. coach Gregg Berhalter said he was impressed by a visit to Qatar’s Aspire national training center in early 2019, when he scouted out potential World Cup stadiums and training sites while laying the groundwork for the national team’s 2020 January camp in Doha. That trip ultimately was canceled amid local tensions that followed the U.S. assassination of an Iranian military commander. Berhalter also said he appreciated Qatar’s ability to find competitive outlets for its developing national team. It’s a situation the U.S. will be in ahead fo the 2026 World Cup, to which it’ll qualify automatically.

“How do you get those competitive games? And that’s what I’ve been impressed with the most, them participating in tournaments like this,” Berhalter said. “It’s not the first time. We had South Korea play in the Gold Cup before the 2002 World Cup. So it’s something that can be done, and perhaps it’s a question to ask the U.S. Soccer Federation, if they’re preparing to enter the U.S. men’s team in tournaments like that.”

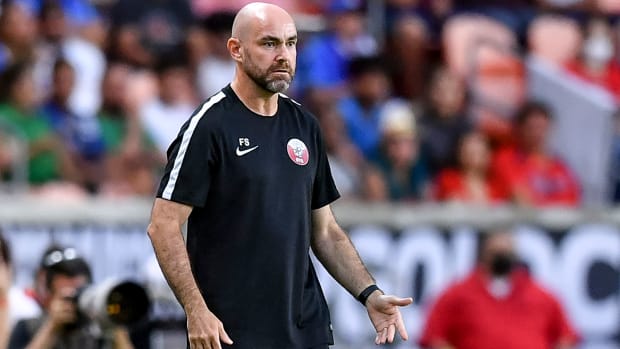

Qatar’s focus hasn’t just been beyond its borders. It’s been working meticulously to build its men’s national team program. Before the 2019 Asian championship, which was won with a 14-1-0 record across qualifying and the finals in the UAE, Qatar’s high point had been two quarterfinal appearances in 11 attempts to win the continental title. In 2017, the QFA promoted Félix Sánchez to national team manager after a decade coaching youth players at the Aspire academy and then the U-19 and U-23 national sides. His development chops were honed at Barcelona, where he coached the club’s U-19 squad.

What Qatar lacks in population and footballing tradition, it’s trying to make up for with chemistry, cohesion and naturalization. While 10 of Qatar’s 23 Gold Cup players were born elsewhere (six in Africa, two in Europe and two in Iraq), all now play for Qatari clubs. A dozen are at Al Sadd, the Doha power coached by Spanish legend Xavi Hernández, and another seven are from rival Al Duhail, which is managed by former France midfielder Sabri Lamouchi. Qatari players can develop at Aspire, then get some seasoning abroad at clubs like Spain’s Cultural Leonesa or Belgium’s KAS Eupen, which Aspire owns. When ready, they return to the Qatari league to compete more directly with and against other national team prospects. That sort of familiarity is rare for a national team, and it provides Sánchez with a foundation of tactical and personal familiarity that’s paid dividends.

Several Qatari players appear to have the talent to do well abroad. But they’re staying put. Forward Almoez Ali, 24, leads the Gold Cup with four goals. Born in Sudan, he was trained at Aspire before playing in Austria and Spain. But he returned to Al Duhail in 2016. Doha native Akram Afif has probably been Qatar’s most exciting and dynamic player this month. Also 24, he’s the reigning Asian player of the year. But after leaving Al Sadd and Aspire for Belgium and Spain, he rejoined Al Sadd in 2018.

“They’re basically represented by two club teams,” Berhalter said. “Having had an inside look on what they do, they almost operate like a club team. The guys come to Aspire to do regen every week, so after their club team games then they all meet up together and do regeneration at the facility there. They get to spend time with each other, look at the games, analyze it. It’s a really unique model and I’m excited to see how they play in the World Cup, because they really have a blueprint for how to prepare.”

Speaking during the group stage, Qatar midfielder Assim Madibo said, “It's a big thing to be honest, for me and my group, because we all came up together with the same coach. I'm with this culture from 11 or 12 years old now, so to make it here to the top it’s a big thing for us. The big dream, we are hoping here to make things, to achieve something big.”

Qatar doesn’t let much stand in its way. It’s battered down traditional doors and found creative (and expensive) ways to account for its historic, technical and logistical shortcomings. With some controversy, it’s been welcomed into just about every corner of the footballing establishment. Qatar is a guest with access, privileges and staying power. And it’ll pose a very real test on Thursday night to a young American team that’s proven to be quite resilient during this tournament.

“It’s a great game for us, to play a semifinal in such a competition like this,” Sánchez said Wednesday. “We are here with the objective to compete, to see how we can compete in a different region than our area. … We are very motivated and happy to reach this stage in the competition.”

More USMNT Coverage: