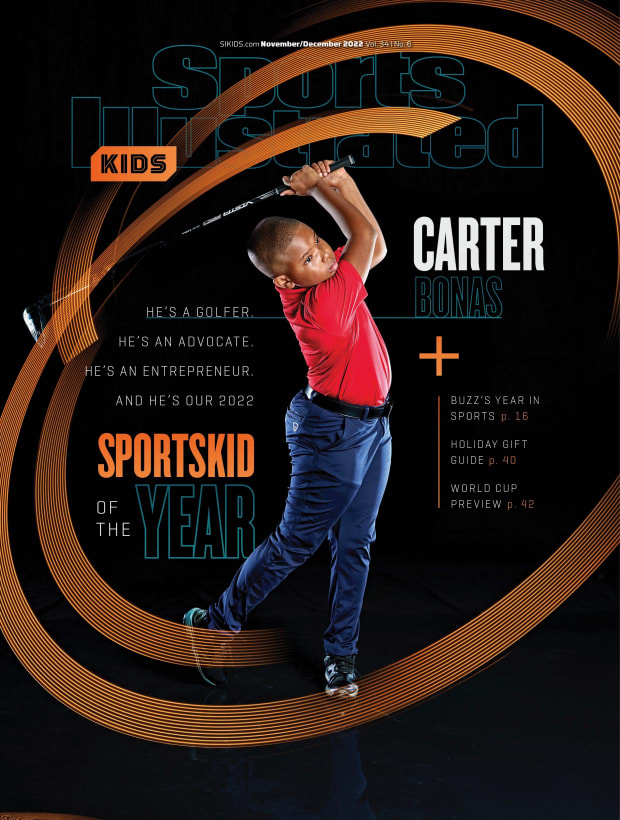

Carter Bonas has leaned into his condition as he’s become a competitive golfer, an entrepreneur and an advocate.

Three years ago, Carter Bonas was being bullied so badly at school he told his principal he didn’t want to go on living. Carter, who was then 8, has autism and was struggling to fit in. He didn’t speak until he was 4, and as he got older he often coped with uncomfortable situations by giving hugs, which opened him up to teasing from his classmates and confused some of his teachers. Tantrums were frequent, and he had a hard time finding a school where he could learn.

Fast forward to today. Carter is a competitive golfer who is pals with Ernie Els. He’s a motivational speaker, delivering talks to students and grown-ups alike. He’s a business owner, selling his own line of golf apparel. And he’s done it all by leaning into the condition that seemed to make life so challenging in the first place. As his Instagram bio declares, Autism is my super power.

Jeffery A. Salter/Sports Illustrated

“He’s learning to channel those obsessions into his business, into his golf, where it’s becoming a positive thing,” says Carter’s mom, Thelma Tennie. “Most kids might give up, but he does not have that ability to give up on something. He has to get it done, or he’s not gonna be O.K.”

As Carter grew up, Thelma and her husband, Eddie Tennie, tried to find an activity that would allow him to meet other kids. “I tried most sports, but I didn’t really like them,” he says. “Some of them there was running around, people pushing you, coaches yelling at you.” Eventually a friend of his mom’s suggested golf. “I like golf because I don’t like being touched,” Carter says. “It’s relaxing. And I love nature, too.”

The family lives in Florida, adjacent to the Country Club of Coral Springs, so Carter began taking lessons with Corey Henry, the pro at the club. Carter wasn’t exactly Rory McIlroy when he started. “Oh, he was terrible,” Henry says with a laugh. But the two worked and worked, for 12 or 13 hours a week, figuring out not just golf but how the teaching process would go with Carter. “We bonded,” says Henry. “Now we have our own rhythm. I know how he learns, and he knows how I teach.”

Now, Carter hits the ball about 215 yards off the tee. Henry estimates he’s played in 15 tournaments and finished in the top four or five in at least half of them. “The sky’s the limit for him,” says Henry. “He has the physical and the mental ability.”

Carter doesn’t just play well; he looks good doing it. When he was 10 he started his own apparel line, Spectrum Golf. “I started my business because I was worried nobody would employ me in the future because I have autism and I had a hard time making friends,” Carter explains. “So I feared that when my mom and dad weren’t around anymore, it would be really hard for me to find a job or just make a living. So I wanted to start my own business, so I would never have to worry about that.”

Golf gear wasn’t his first idea. “He wanted to sell the vegetables in his garden,” says Thelma. “After he sat down, did the math and realized how much money he needs to support himself as an adult, he realized our backyard was not big enough to grow enough produce.” He also thought about selling rocks from the front yard.

Finally inspiration struck, and Carter hit upon something that people might actually want to buy. He spends a lot of time in the hot sun, and because of his autism he’s very sensitive about how things feel against his skin. “We were spending lots of money on clothes that were supposed to be comfortable for me, but they weren’t, because I have a skin sensitivity,” he says.

So he and his parents ordered sample after sample online and eventually found fabrics that worked. He came up with the name Spectrum Golf and a logo, an S and a backward G. “I was writing the SG, but I wrote the G backwards because I’m dyslexic,” he says. “My mom said to fix it, but my dad said it’ll look good. And it did.”

Carter isn’t the only one repping the brand. He met Anita Uwadia, who plays on the LPGA’s Epson Tour, and after chatting with her became her sponsor. He also had the chance to meet Els, the former U.S. Open winner, who has an autistic son. Els and Carter spent time together when Els was at a tournament in Florida last February. Els gave Carter some pointers, and Carter gave Els some swag. Els also invited the family to visit his Els Center of Excellence, a facility for autistic people, and the two recently played a round together at Els’s course in Egypt when Carter’s family was on vacation. “What Carter’s done, starting up his own company and carving out a place for himself in society, that’s what we’re trying to achieve with the kids at our center,” says Els. “Carter’s story is an inspiration to other kids on the spectrum, so it was wonderful to have him there.”

Jeffery A. Salter/Sports Illustrated

The kid who didn’t speak until he was 4 is not shy about sharing that story. “I am amazed and shocked by him every time he gets onstage or in front of students,” Thelma says. “He lights up; he loves sharing how he overcame his struggles and how he works every day to overcome them.”

It’s an ongoing process. It’s still hard for Carter to make friends with kids his own age. He has a tough time sharing his toys because he can’t help but worry something will get broken. “For him, let’s play means you sit in the room with me, you play with your stuff, I play with my stuff,” says his mom. “But he’s getting better.”

And that’s at the heart of the message he delivers when he talks to crowds. “You can do anything,” Carter says. “You just have to believe in yourself and always stay positive.”

More Daily Covers:

• How the 2002 USMNT Set the Course For This Year’s Squad

• Raheem Sterling, in His Element

• The Upside Down World of Long Snappers