The death of George Floyd motivated his hometown team to double down on its commitment to battling for equality.

Brandon Williams will never forget the phone calls. For years, starting around 11 p.m and sometimes lasting 90 minutes, Williams and his uncle, George Floyd, would catch up on all that night’s NBA action. From the frustrating hometown Rockets to mini miracles acted out by LeBron James or Russell Westbrook (two of Floyd’s favorite stars), they sifted through it all.

Growing up under the same roof in the Third Ward, Williams and his uncle—who was more of a father figure—bonded over all sports. But basketball was the game they both played in college. Rehashing the NBA’s evening slate eventually served as a way for them to preserve their connection, first when Williams went off to attend Utah State University Eastern, and, a few years later, after Floyd caught a bus up to Minneapolis to try to get his life back on track.

Almost exactly 11 months after Floyd was killed in broad daylight by Derek Chauvin, the now former Minneapolis police officer was tried and found guilty of second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter for kneeling on the restrained, unarmed Black man’s neck until his heart stopped beating.

Hours after the powerful verdict was read on April 20, the Timberwolves beat the Kings, 134–120. In the locker room afterward, Gersson Rosas, Minnesota’s president of basketball operations, told the team that the game ball would be presented to the Floyd family.

One week later, Williams, 30, and two of Floyd’s brothers, Philonise and Rodney, were invited to attend a game in Houston between the Timberwolves and Rockets, where they were hand-delivered that ball, along with a custom Wolves jersey that had Floyd’s name stitched on the back. The jerseys Karl-Anthony Towns and Anthony Edwards had just worn against the Rockets were also given to Williams and Philonise, who loves the reigning No. 1 pick.

“It felt surreal. We get a lot of love and support from a lot of people, but I think that one meant the most because our whole family, like, we lived and died sports,” Williams says. “When we met those guys, man, they showed nothing but love. You could tell that they probably wanted to meet us more than we wanted to meet them, which says a lot. … To see guys that [George] would probably admire. Guys that he would watch and guys that he was a fan of, it would have meant everything to him. And I think that’s why it means so much to us.”

Gifting a game ball and a few jerseys was a nice, symbolic gesture that brightened up a grieving family’s day. The Timberwolves’ commitment to the cause of racial equality goes deeper, though. “I think for us we were just trying to do our part to let them know that we’re here with them,” Towns told reporters after the game. “That this game of basketball is only just a little part of who we are.”

As highly visible members of a reeling community, witness to ritualistic injustice where they live and work and are raising their own families, the team has collectively embraced the responsibility their global platform affords during a tectonic time when fighting for racial justice should be seen as the do-or-die undertaking it’s always been.

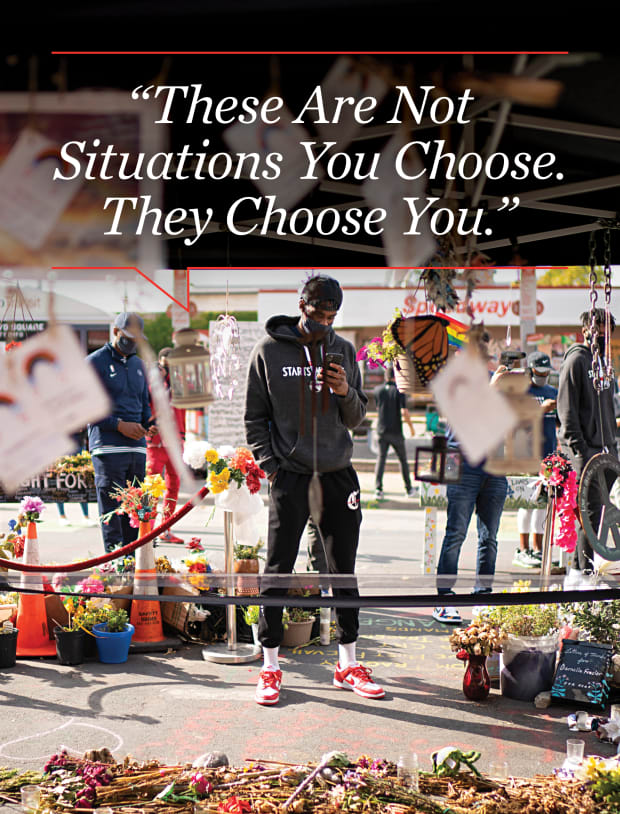

“I'm a minority, so I have a sense, I have a perspective. But seeing what [our players] were feeling really helped me understand just how proactive we needed to be,” Rosas, who is the first and only Latino to head an NBA front office, said last month. “I’ve often said, these are not situations you choose. They choose you. There’s a sadness. There’s a tragedy. But there’s also an urgency and a responsibility that comes with that.”

For the past year, the U.S.’s eyes have been fixed on Minnesota, the tense epicenter of this country’s most recent racial reckoning and social justice movement. It’s where Floyd was murdered. It’s where his murderer was convicted by a jury of his peers, with results that threatened to reignite another violent uprising. It’s where, in April, 20-year-old Daunte Wright was killed by now former police officer Kim Potter—whom the Brooklyn Center PD claimed mistakenly pulled the trigger of her gun instead of the taser she thought was in her hand.

The Wolves have responded to these traumas in myriad ways, with an understanding that they can and should help vulnerable areas of a broken system. Even with no solution in sight, ignoring the problem was not an option.

In the immediate aftermath of Floyd’s death, Rosas had numerous conversations with his players. Many were angry and frustrated; he let them know the organization “had their backs” and would provide every resource it could in the days, weeks, months and years ahead. He also preached pragmatism and strategic thinking.

“We don’t want to react off emotions,” Rosas says. “We want to react off information in order to create sustainable solutions or approaches. My guidance to the players was, ‘Let’s be educated about this. If we’re going to do anything, let’s do it with purpose. Less is more, to start out with.’ ”

In late May and early June, the front office scheduled video calls with local politicians (including the mayor of Minneapolis, Jacob Frey), community leaders, Minneapolis Chief of Police Medaria Arradondo and criminal justice experts who could inform players, answer questions and allow them a safe space to process the pain and hurt that came with Floyd’s death.

“It was cool for the Timberwolves to be proactive that way, and put us on calls with people who are in places of power, to actually demand direct change,” Minnesota guard Josh Okogie says.

One of the first speakers Rosas sought was Tru Pettigrew, a community bridge builder who opens lines of dialogue between police departments and the diverse populations they ostensibly aim to protect and serve. Rosas and Pettigrew have known each other for more than two decades, starting when Pettigrew was a marketing executive.

But in 2014, as a reaction to Michael Brown’s being killed by then police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Mo., Pettigrew changed his focus out of “personal feelings of frustration, fear and concern for my son,” he says. Pettigrew was living in Cary, N.C., an affluent, predominantly white town. He grew up in Baltimore, in a neighborhood beset by violence, crime and addiction. He experienced excessive force by police as a child, and then, as an adult after moving to Los Angeles, he remembers being thrown to the ground, having a gun pointed at his head and being taunted by officers who threatened his life.

Those experiences convinced him to dedicate his life to holding law enforcement accountable, which aligns with what the Timberwolves aspire to do. In December, they hired Pettigrew full time as their vice president of player programs/diversity and inclusion.

“I’ve built relationships with law enforcement, with district attorneys, with prosecutors, with defenders in different states across the country,” he says. “So I’ve really invested a lot of time, energy and resources into educating myself on the nuances of our judicial system and our law enforcement system.”

Pettigrew traveled with the team all season. He checked in with players daily and—in addition to being an educational asset who, for example, walked many of them through developments in the Chauvin trial as it unfolded—talked about different ways they can best leverage their status in society to impact change.

“In corporate America, you always hear the phrase ‘the things that keep me up at night,’ ” Pettigrew says. “I talk with our guys about ‘what gets you up in the morning?’ I know it’s basketball, but is it [also] making sure there’s a better world for your sons or your daughters or your family? Making sure you live in a world where people don’t have to go to sleep worrying about the safety of their children. Is it living in a world where we can eradicate racism and people aren’t judged or assessed based on the color of their skin? Like, what are the things you’re passionate about? Is it educational empowerment and making sure that the people that come from communities like you have financial literacy to build a life for themselves? That passion is what sustains us.”

A key step, in Pettigrew’s view, is for high-profile Timberwolves to forge relationships with members of the local police; in April the team was in communication with Chief Arradondo about having “a series of courageous conversations” that will aim to combat some of the mistrust and resentment that’s caked into how both sides feel about the other.

“I guess the question that we have to all ask ourselves is what are the alternatives? If we do nothing then we can’t expect anything to change,” Pettigrew says. “We want to hold all of the leaders in this community—from a government standpoint, from a business standpoint, from a law enforcement standpoint—we want to hold you accountable. But...it’s hard to hold someone accountable that you’re not in a relationship with.”

To put it in the mildest terms possible, the challenge is daunting. At times unbearably so. Especially for a basketball team that would otherwise be able to focus its attention on the primary reason they were brought together. Players, coaches and front office executives want to help. They also aren’t trained in all the ways they can best do so, or are always able to balance the full-time hours both jobs entail. There’s no road map or guarantee of success, either. But what they do have is intention, commitment and clout.

“I’m a big believer that there’s always a purpose for anything that we do,” Rosas says. “And if my purpose to be part of this organization here now is to lead them through this, I’m where I’m supposed to be, doing what I’m supposed to be doing. There’s so much work that needs to be done. It can become overwhelming. ... I wish we were more involved in basketball at this time. But our reality demands more out of life right now.”

When the 2019–20 season ended, Okogie went down to Atlanta to stay with his family. In early May, as he planned a trip back to Minneapolis for offseason workouts, footage of Ahmaud Arbery’s getting fatally shot by two white men (one a former police officer) while jogging in a nearby town was leaked by a lawyer. While following that tragedy’s developments as they evolved in real time, Okogie read up on Elijah McClain, a Black man who in August 2019 died in police custody in Aurora, Colo.

On the day after Okogie traveled back to Minneapolis, Floyd was murdered. “I was like, ‘Damn, I literally can’t get away from this,’ ” he remembers. “I didn’t know what to do and I felt like I needed to do something.”

Days later, Okogie stood in solidarity beside Towns, former NBA player Stephen Jackson, Jamie Foxx and others at an emotional press conference held at Minneapolis City Hall. Okogie later attended Floyd’s funeral. “You could literally hear people’s cries for equality, for justice, for police accountability,” Okogie says. “It was powerful, to say the least, to go outside and feel the soul of the city.”

He’s spent the entire season going out of his way to educate himself on law enforcement, peppering the Timberwolves director of team security Tony Adams—a retired, 30-plus year veteran of the Minneapolis Police Department who was promoted in December to his current role—with questions.

What are the requirements to be a police officer? What are police officers trained to do? When it came to Floyd’s death, Okogie wanted to know whether there was anything else that could have been done by the officers who were on the scene, and how Floyd’s alleged use of a fake $20 bill could possibly lead to the cruelty that then occurred.

“When you speak, you want to make sure what you’re saying is factual because somebody will try to discredit everything you say if one thing might have been a tad bit off,” Okogie says. “Especially when you speak about something like this.”

Okogie acknowledges the right to a fair trial but couldn’t stand to watch Chauvin’s, because he couldn’t understand someone trying to defend themselves through an official process despite their heinous crime being on video and already seen by the world.

More than anything, he wants officers to be held accountable for their actions. During a recent press conference he cited Chris Rock’s famous bad apples bit, wherein the comedian explains why some professions can’t afford to employ people who can’t or won’t do their job without making mistakes, be it police officers or commercial airline pilots. Okogie then expands on that with his own analogy.

“If I’m in the gym and I’m working on my three-point shots or whatever with my trainers, and I miss, I’m not really worried about how much I’m missing, because the shots that I make don’t count, the shots that I miss don’t count. But if I’m in a game, the misses really count. Every turnover, every assist, every rebound, every point, everything counts,” Okogie says. “The police today feel like they’re just working out with their trainers. The shots, the makes and the misses don’t really count. The lady who thought that she had a taser in her hand but she had a gun. For me that's you being in the gym with your trainers. I want the police force to be in game mode, where everything counts. Every miss is a human life.”

On April 11, while Chauvin’s trial was underway, Wright was pulled over in Brooklyn Center, a city that borders Minneapolis, for having expired registration tabs on his license plates. Minutes later, Potter fired a bullet into his stomach. “In this country, if you’re Black and you get pulled over by the police,” Brooklyn Center Mayor Mike Elliott said after the killing, “you have a very much higher chance of being dead just because you’re Black.”

Already on edge, some players fell into disbelief. Pettigrew remembers them asking, “When will it stop? Why does this continue to happen to people that look like us? What do we have to do? What needs to change for this to stop?”

The Timberwolves’ next home game, against the Nets, was postponed a day. Before they took the court, a team manager asked Okogie whether he’d wear a warmup shirt that read “WITH LIBERTY AND JUSTICE FOR ALL.” Okogie agreed, then rallied his teammates and Minnesota’s next three opponents to wear them as well. But he wanted to take the action further.

“Sometimes just raising awareness isn’t enough,” he says. “I mean, if what just went on for the past year in America hasn’t raised enough awareness, obviously wearing a shirt to an NBA game won’t.”

The shirts were eventually auctioned off, and Okogie says around $25,000 was raised for Wright’s family, with Timberwolves future owner Marc Lore matching that total.

Before the auction, the Timberwolves connected Okogie with charity and financial specialists familiar with everything he’d need to pull it off. “I just think that it’s really cool to be able to plan something or have an idea in my mind, and [the front office backs] it 100%,” Okogie says. “All I had was a vision, and they literally gave me all the tools I needed to bring the vision to fruition. There’s such limited things you can do because your time is mostly spent on basketball, but when they’re able to match you with the right people and the right resources it just makes everything so much easier.”

That auction did some good for the community. But the Timberwolves’ strategy is aimed to prevent killings from taking place, not to react to them after they happen.

“If we can provide a fix for a specific incident, one isolated incident, then that is phenomenal,” Pettigrew says. “But if we continue to fix a wound but don’t really change the conditions, then we’re allowing people to continue to live in a world that is continuing to put them in harm’s way, and it's continuing to traumatize them and make them sick.”

Brandon Williams hasn’t had much time to rest. His family has taken up the cause of racial justice, traveling across the country to stand with other victims that have been devastated by police brutality. As we talked earlier this month, he was planning a march and rally in Houston to commemorate the anniversary of his uncle’s death.

Williams eventually wants to honor his uncle by devoting a room in his home. He pictures the Timberwolves’ game ball in a glass case, with Towns’s jersey in a frame beside Floyd’s own custom version. (“It took like two days for the sweat to dry,” Williams says, laughing, about Towns’s jersey. “So I’m definitely not wearing it.”)

Through his grief, Williams still struggles to process all the attention and sympathy that’s been extended to his family. But he’s grateful for it all, including what has come from NBA teams and players. Williams is almost surprised by how willing and loud their support for change has been.

“Oftentimes you don’t see people that’s in their position use their platform, because a lot of times it’s about money and people are scared to lose endorsements. People are scared of the responses they’re gonna get, the criticism or the backlash that can come with it,” he says. “To see guys of their stature speak out, and for it to be genuine and heartfelt, it means everything, man. It helps us get through those rough days when the cameras aren’t there. You know, the days when you’re actually grieving and you just more than anything wish George was here.”

Williams stops to think about what his uncle’s reaction to everything the Timberwolves have done would be. “It’d probably be priceless,” he says. “He was so humble and so giving and caring that he would just kind of be in awe like, ‘Man, all this for me?’ I can just hear him now: All this for lil ol’ me?”

More George Floyd Coverage:

• Behind the Timberwolves' Fight For Racial Justice

• Where the Confederates Fell, Arthur Ashe Still Stands

• 'We Weren’t Welcome When This Guy Was Around—So Now He’s Not Welcome When We’re Around'