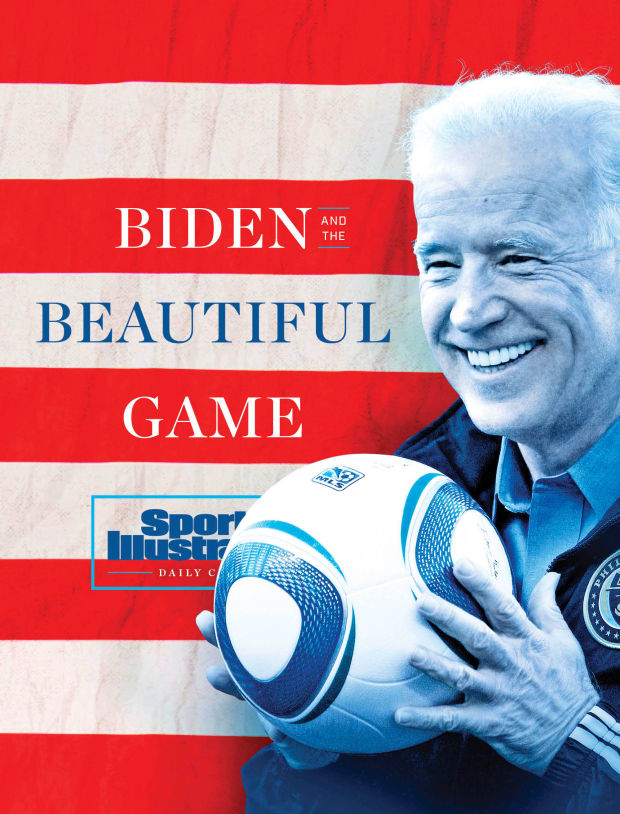

Joe Biden has been around more of U.S. soccer's key moments over the last decade-plus than you'd think–and that'll continue while in office.

For four years—through a World Cup in South Africa, a season in Germany, three years in Mexico and around two dozen national team matches across the U.S., Europe and Latin America—DaMarcus Beasley kept the coin in his toiletry kit.

He placed it there after receiving it as a gift at the conclusion of a White House visit—it seemed as good a place as any to store it for a while—but then never had a reason to take it out. It remained mixed in with his grooming supplies, transported between hotel rooms and locker rooms and back, out of some mix of habit, superstition and inertia.

“Every once in a while you clean out your bag, your toothpaste is done or whatever, but I always kept the coin in my bag,” Beasley said.

In May 2010, Beasley was part of a U.S. national team delegation that was welcomed by President Barack Obama, Vice President Joe Biden and former President Bill Clinton to 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. NW in Washington, D.C., where they’d share a few words and take a few pictures before heading to South Africa for the World Cup. It was supposed to be a quick visit but the U.S. Soccer Federation went all out anyway, embroidering team jackets for the players and staff to wear and fitting everyone with brand new dress pants and shoes.

“I told the team prior to that, ‘Guys, this doesn’t happen. You don’t usually go to the White House for a visit until you win something, and we’ve got two presidents and a VP,’ ” then-U.S. Soccer president Sunil Gulati said. “That doesn’t normally happen.”

Photos were shot, pleasantries were exchanged and Obama and Clinton took their leave. The rest of the group was milling about waiting for their bus when Biden, who was still hanging around, was approached by U.S. team trainer Jim Hashimoto and press officer Michael Kammarman. Like Biden, Hashimoto and Kammarman were University of Delaware alumni. Biden was happy to reminisce for a few minutes, and he then asked what the team was up to. The plan was to board the bus and head straight back to Philadelphia, where there was training that afternoon and then an exhibition game against Turkey two days later.

No, Biden meant, what are they up to right now?

Waiting for the bus.

There was Biden’s opening. Within moments, the national team was off on an impromptu tour of the West Wing that included the Oval Office, the Roosevelt Room and a once-in-a-lifetime group chat in Biden’s own office. As they left, Biden gave each member of the U.S. delegation a gold-and-blue vice presidential challenge coin as a memento of their unplanned time together.

“He told the story about what the coin means. Just in layman’s terms, basically if you go into any bar—it started at military bars—and you put it in front of a higher rank, they have to buy you a drink,” said Beasley, the quick and skillful midfielder who was on his way to a third World Cup. “We thought that was so cool. That would probably never happen, because we don’t know if we’d ever be in position to even experience that, just putting the coin on the bar table in front of a general and have them buy you a drink. But just Biden telling the story about what it meant was pretty cool.”

Biden had made the secret and exalted—these rooms that were the seat of such power and these traditions of men and women who represented the country in such serious and symbolic ways—seem accessible and familiar. That struck a chord with Beasley.

“So that’s why I kept the coin. I just kept it because maybe it gave me luck,” he said. “I had it in my bag because of the story he told. You get a gift from the White House, from the vice president, you just keep it in your bag.”

Beasley never intended to keep the coin among his toiletries for four years. He wasn’t planning on playing in a fourth World Cup—no American man ever had. And he certainly didn’t imagine that Biden would become such a familiar presence, someone whose path kept intersecting with U.S. soccer’s throughout his eight years as vice president and then again as he pursued the top job in 2019-20. It turned out that Beasley and Biden running into each other in a bar, so to speak, wasn’t that far-fetched.

***

On Wednesday, once Biden is inaugurated as the nation’s 46th president, American soccer will have a surprisingly familiar friend in the White House. On a superficial level, it makes some sense for the chief executive to maintain ties to the sport. Soccer may not be the country’s national pastime, but it’s by far the most frequent way the U.S. projects its sporting face to the world. Soccer is the only significant sport with standing national teams, and the games those teams play are monitored across the globe. Americans playing for professional clubs abroad, especially the cohort of young men now making their mark at some of the top teams in Europe, essentially are ambassadors. And soccer is a common thread among nations through which leaders can network—just take a look at the luxury suites at a major FIFA final.

Biden gets this. In 2014, he told a story about attending a state dinner connected to the inauguration of Chilean President Michelle Bachelet and sitting with the leaders of at least four Western Hemisphere nations, as well as Spain’s Felipe VI shortly before he became king. The topic was soccer.

“Each one, bragging about their bona fides … who scored when. I mean, this went on for the entire lunch,” Biden said, adding that it wasn’t election results or GDP that Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff was boasting about, it was her country’s five World Cup titles.

“It’s the most unusual sporting event I’ve ever attended, and I’ve attended thousands probably in my career,” said Biden, who’s been to three World Cups (two men's, one women's). “It’s a feel, and you can feel it even before you get anywhere near the stadium. You can feel it before you even land. It’s in the air. It’s a palpable sense of energy that I’ve never quite experienced before. And it’s consequential. It is the most consequential sporting event in the world, and it’s amazing how not just interested, but how deeply, deeply, deeply passionate every country is about the World Cup.”

But Biden is adept at making connections feel more than superficial, even when his appearance represents just another entry on a politician’s schedule. That ability to feel, say the people who’ve met him, has helped make his relatively frequent run-ins with American soccer seem just a bit more personal. That’s why Beasley valued that coin so highly, and it’s why U.S. Soccer believes it can strengthen that relationship as it prepares to cohost the 2026 World Cup with Canada and Mexico.

Biden’s personal experience with soccer is probably common for Americans his age (78). He wasn’t familiar with the game growing up in Delaware, where he was an accomplished high school wide receiver. He dabbled in baseball as well. But his sons, Beau and Hunter, came of age in the 1970s, when youth soccer started to make significant inroads in many U.S. suburbs. What was foreign for the father was part and parcel of growing up for the sons.

“My boys were five and six and started in a county league, and it went from 50 kids to 600 in three years. I don’t even think the high school that I went to had a soccer team,” Biden said in 2015. “Beau played and was captain of the soccer team … and I never played soccer, but I watched all Beau’s games.”

Now it’s front and center for his grandchildren. Beau’s daughter Natalie helped Biden kick off the Philadelphia Union’s 2010 MLS expansion season. And Hunter’s daughter Maisy is a devoted soccer fan who played goalkeeper for her D.C. high school team and accompanied her grandfather to the 2015 Women’s World Cup final in Vancouver. Family has pushed Biden closer to the sport.

“My girls—my granddaughters—and my grandson, they all play soccer,” Biden said just before the 2014 World Cup. “And they all asked only one thing. At Christmastime, I always sit with the kids, the last five years [as VP], and say, ‘Well, where do you want to go this year?’ Because one of the great advantages of being vice president, I’m able to take—if I’m not going into a war zone—one of my grandchildren with me. … And the only thing all my girls said is they want to go to the World Cup.”

***

Family was the catalyst for Biden’s first significant soccer moment as vice president. Beau, who died in 2015, was good friends with a local developer named Rob Buccini. Buccini’s company was involved in the construction of the Philadelphia Union’s stadium in Chester, Pa., and he became a minority investor in the new MLS club. While the arena was being finished, the Union’s first few home games in the spring of 2010 were scheduled to take place at the Eagles’ Lincoln Financial Field.

“Beau actually was a fan of the game, God rest his soul, and he came to Philadelphia Union games. Beau and Rob were Delaware guys and grew up together and had a relationship,” recalls Union founder and former CEO Nick Sakiewicz. “Buccini’s suite was two doors down from mine, and whenever Beau was in Rob’s suite I’d go over and say hello to them. We’d have soccer conversations, and [Beau] was pretty knowledgeable.”

Sakiewicz and his staff were busily preparing for their inaugural home game against D.C. United, for which they’d sold nearly 35,000 tickets, when he got a call from Buccini.

“‘He said, ‘I think Beau can pull this off.’ And then we just kind of went into overdrive,” Sakiewicz says.

The vice president was coming.

The security logistics were significant, and that included the closure of exits off I-95. When Joe Biden took the field alongside Natalie, Philadelphia mayor Michael Nutter and MLS commissioner Don Garber, there still were thousands of fans waiting to get inside.

By then, Sakiewicz had enjoyed the chance to chat a bit with the VP.

“He was very talkative, like in the staging area before we went out to midfield,” Sakiewicz says. “He was very conversational about soccer. He knew the sport was exploding in the U.S. He said he watches the U.S. men and women, and we talked about the women’s national team, because they’re so successful. He said how great it was to have an MLS team playing in Chester. He knew all about the stadium, about the redevelopment that we were trying to spark on the riverfront. I was really surprised how knowledgeable he was about the project. He called it the stadium in his backyard.”

Biden wasn’t as comfortable, however, with actually kicking a soccer ball. The idea was to have him join Philadelphia soccer legend Walter Bahr, a member of the famous 1950 U.S. World Cup team, at midfield, and then pass the ball to Union captain Danny Califf.

“He was like, ‘I don’t know. I’m not used to kicking things. I’m usually throwing things,’ ” Sakiewicz says. “So we were showing him. ‘Use the side of your foot. Don’t use your toe’—kind of giving him some advice about how not to make a fool of himself.”

In the end, as comfortable as he is in the spotlight, Biden deferred to Natalie. His five-year-old granddaughter did the honors. Sakiewicz, now the commissioner of the National Lacrosse League, has the ball she kicked on a shelf in his office.

Biden didn’t stay for the game, and even though the fans waiting outside missed the Union’s first home goal, which Sébastien Le Toux scored in the fourth minute, the Frenchman obliged by scoring two more in a 3–2 win.

“[Biden] was awesome. When he came into the stadium, he shook hands and gave everyone big congratulatory hugs. He was awesome, and his family was awesome,” Sakiewicz says. “We were honored to have him there. It was absolutely the cherry on top of the cake. It was a long slog, bringing that team to Philadelphia.”

Just six weeks later, Biden was chatting with Hashimoto and Kammarman and inviting the U.S. World Cup squad to take its improvised West Wing tour. There, he was much more in his element. If you want to put Biden at ease, don’t ask him to kick a ball—ask him to hold court. He’s clearly someone who’s energized by being around others. He’s comfortable talking to just about anybody, and it should come as no surprise that he’s interested in athletes. Football and baseball helped shape and embolden Biden as a young man growing up with a stutter.

“As much as I lacked confidence in my ability to communicate verbally, I always had confidence in my athletic ability,” he wrote in his 2007 memoir, Promises to Keep. “Sports were as natural to me as speaking was unnatural. And sports turned out to be my ticket to acceptance—and more. I wasn’t easily intimidated in a game, so even when I stuttered, I was always the kid who said, ‘Give me the ball.’ ”

So on that day in May 2010, Biden had a couple dozen world-class athletes at his disposal, and he was going to make the most of it. He invited the team into his office, asked them all to take a seat and proceeded to engage them for what Gulati estimated was about 30 minutes. Photos show the players bunched together in the room, standing along the edges or crammed onto one of the two sofas in the center. Assistant coach Mike Sorber somehow wound up in Biden’s desk chair.

“We just chitchatted. We just talked. We talked about the World Cup,” Beasley says. “I think a couple guys asked him a couple questions. He was very personable, very warm, very open, and very cool. You could tell why him and Obama are very good friends. They kind of have that same personality with people—with people they don’t even know.”

Biden asked a couple of his guests where they went to college before realizing that by then, gifted young players were turning pro before heading off to school. He told the team all about how the West Wing functions and what the vice president does. He referenced the U.S.’s rough go at the 2006 World Cup and expressed hope that 2010 would be better. Then he sent them on their way with the coins, telling them he’d be seeing them again soon.

“When you go to the White House, everybody’s excited. You don’t want to make a mistake. You don’t know how to act. You’re in a historic place, not just in America but in the world,” Beasley says. “So to be there and for him to take his time and really be a normal—not the vice president of the United States but just be a normal human being and sit down and talk to us—that was memorable.”

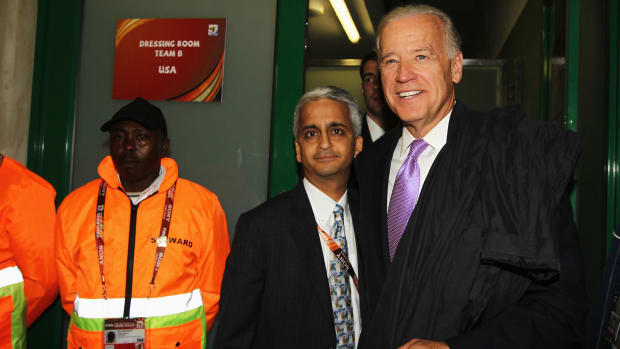

Soon they all were off to Africa—the World Cup team to its base camp in Irene, just south of Pretoria, where it would prepare for its tournament debut against England, and Biden to meetings in Egypt and Kenya before heading to Johannesburg. There, Biden visited the U.S. Consulate and met with South African Deputy President Kgalema Motlanthe, with whom he joked about the prospect of a South Africa–U.S. World Cup final. Biden attended the opening match between the hosts and Mexico. And then the next morning—the day of U.S.-England—he joined Gulati for a meeting with FIFA president Sepp Blatter.

“A big part of the reason he came over was to help us pitch for the [2022] World Cup,” Gulati says.

Obama had been planning to go himself, but he stayed behind to deal with the effects of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill that April. So Biden went to South Africa instead and found himself face to face with Blatter, who in some ways was as powerful as a head of state. FIFA’s Executive Committee would vote for the 2018 and 2022 hosts six months later.

“We talked at length about what the United States had to offer the World Cup and what the World Cup had to offer the United States,” Biden said in a video produced by the White House. “I’m hopeful that we have a real clear shot that by the end of this year, getting picked as the site of one of the next two World Cups.”

Blatter, Gulati and Biden convened in Blatter’s room at the Michelangelo Hotel in Sandton, a ritzy suburb of Johannesburg.

“None of Blatter’s people came. So it was just the three of us up in his suite,” Gulati says. “And Biden was pitching the World Cup for us. He was fantastic at doing it. All the little things when you’re trying to be friends with someone—you touch them on the knee. Blatter said, ‘Well, I have only one vote.’ [Biden] basically said, ‘Yeah, but the referee is very important in all of this.’ ”

Biden was just as quick on his feet once the meeting was over.

“We’re leaving, and we’re running into a few people along the way. [Franz] Beckenbauer, we run into on the elevator,” Gulati recollects. “And then we get to the lobby, and there’s people in the lobby, and [Biden is] just phenomenal. He stops. He starts talking to people. Everything you hear about him and the way he is, he starts talking to people he doesn’t know. He goes over and talks to the woman at the registration desk. ‘So where are you from?’ Just engaging in a way that politicians can if they’re warm and personable.”

That evening in Rustenburg, a small city about 75 miles northwest of Johannesburg, Biden asked if he could meet with the national team ahead of its match against England. That typically isn’t done. Locker room visits are for postgame. But Biden was a friend, so coach Bob Bradley made an exception. Biden and his wife, Jill Biden, made their way down to the depths of the Royal Bafokeng Stadium, and the vice president delivered a few words to the team. The Bidens then returned to their seats and watched the Americans tie the favored English, 1–1, before going on to win their first-round group for the first time in 80 years.

Biden would miss out on the next two significant American soccer events. He intended to go to Zurich in December 2010 to help Clinton make the U.S.’s final case to host the 2022 World Cup, but he was unable to make the trip. Biden’s ability to work a room probably wouldn’t have mattered, as Qatar won a vote that remains shrouded in suspicion. FIFA has since overhauled its system for awarding World Cup hosting rights, the Executive Committee was disbanded and, in 2015, Blatter himself was suspended from all FIFA activities for six years for offenses unrelated to the 2022 bid.

The U.S. suffered another wrenching defeat in Biden’s absence in the summer of 2011, when the women’s national team blew two leads to Japan and then fell on penalty kicks in the Women’s World Cup final in Frankfurt, Germany. Jill Biden and Chelsea Clinton were there, however, and the future first lady said a few words to the devastated American players back at the team hotel that evening.

***

“Vice President Joe Biden,” Gulati yelled over the din of the celebrating locker room inside the Arenas das Dunas.

Thanks to a resolute defensive performance and a stunning, 86th-minute header from 21-year-old defender John Brooks, the U.S. defeated Ghana, 2–1, in its 2014 World Cup opener. That victory in Natal, Brazil, not only put the Americans on course to reach the second round, it cleansed the palate of devastating losses to the Black Stars at the 2006 and 2010 tournaments. The nemesis was defeated. Spirits were soaring.

“We’d beaten Ghana. The team’s excited, and you’ve got the vice president of the United States there, so it’s pretty cool,” Gulati says.

Biden and his entourage—including granddaughter Maisy—entered the locker room and congratulated the team. Biden saw coach Jürgen Klinsmann standing nearby and immediately joked that when Clint Dempsey scored the U.S.’s first goal shortly after kickoff, Klinsmann seemed happier than Biden was after the 2008 election.

Biden began to make his way around the room. Beasley, who’d just played 90 minutes at left back, had to think fast. The players hadn’t known Biden was coming. Beasley rifled through his toiletry kit.

“Mr. Vice President,” he said.

Biden turned.

“I want to show you—I still have the coin from last time.”

It was Beasley’s second moment of triumph that day.

“I had the coin in my hand, and I was kind of nervous. I was trying to get his attention,” he recalls. “It was so surreal. He was right in front of me, and I didn’t know how to interrupt him from talking. I didn’t know how to approach the vice president of the U.S. How do you do that? It made it easier because it wasn’t a formal setting. He was talking, going around, shaking hands and this and that, and then he finally got to my area.”

Biden seemed overjoyed.

“Well, I owe the drink,” Biden exclaimed, before putting his arm around Beasley for a photo.

“He wasn’t thrown off by it. He has a quick wit. It was great. It was really great,” Beasley says. “You couldn’t have written a better script for that moment for me, how I had the coin and how it happened and winning the game and how it all ended—a really cool moment.”

As Biden left, he turned toward Beasley.

“Hey man, any time you want to collect,” he said. “I owe you!”

***

There were more celebrations the following summer as the U.S. women exorcised their World Cup final demons and thrashed the Japanese, 5–2, in Vancouver.

Biden was there at BC Place with his wife, several grandchildren, Sasha Obama and National Soccer Hall of Fame members Mia Hamm and Cobi Jones, among others. Although the Bidens were brought down to the field following the game, interaction with the team was postponed until October, when the USWNT and U.S. Soccer officials visited the White House. Obama was the primary MC that day, but Biden was in attendance. He greeted the players privately and was presented with a national team jersey.

Biden’s tenure as VP was coming to a close, but his relationship with the world champion women would strengthen during his subsequent run for president. Meanwhile, Jill Biden had one more unplanned run-in with the American men in the fall of 2016, when her trip to Cuba coincided with a historic friendly staged in Havana. Hurricane Matthew had devastated parts of the Caribbean in early October, and, although the players and coaches could travel, Gulati’s flight was canceled. He was able to improvise, however, thanks to U.S. Soccer’s connections at the White House. A few phone calls were made, and Gulati was on his way to Andrews Air Force Base for a flight to Cuba aboard Air Force Two.

Jill Biden visited the team at its Havana hotel, said a few words and then attended the USA’s 2–0 win over Cuba.

***

Between Biden’s visit to Vancouver and the start of the 2020 presidential primaries, Megan Rapinoe had evolved from women’s national team star to FIFA Player of the Year and social justice icon. She was the 2019 Women’s World Cup Golden Ball winner, and, as an outspoken advocate for racial and gender equity, she became the most recognizable face of the WNT’s equal pay crusade.

In April 2020, Rapinoe hosted Joe and Jill Biden in a lengthy Instagram Live conversation, during which Jill Biden showed off her partially-dyed purple hair “in solidarity with pay equity,” and Joe Biden said, “You made me a hero,” with a signed WNT jersey he could present to his granddaughter.

The men’s national team is the vehicle through which a president or VP can relate to more of the world. But the women’s national team possesses the star power at home.

Rapinoe offered to be considered as Biden’s eventual VP nominee, to which Biden responded, “You would have to take a pay cut to become vice president.”

Rapinoe answered, “You know I’m not into that!”

Biden said, “You should get the same pay your colleagues, that men get. Not a joke. We’ve been hollering about that for a long time.”

A few days later, a U.S. federal judge dealt a massive blow to the WNT’s year-long pursuit of relief, declaring via summary judgment that the U.S. women didn’t face discrimination from U.S. Soccer and by some measures had been paid more than the men. In addition, in dismissing a significant part of the lawsuit, the judge found that the WNT had rejected a contract similar to the one signed by the MNT.

Left with only a dispute over select working conditions to litigate, the WNT began the process to be able to appeal and vowed to keep fighting.

Then Joe Biden emerged with a stunning show of support.

U.S. Soccer didn’t respond at the time. Gulati’s successor as president, Carlos Cordeiro, had resigned in March because of sexist language used by attorneys working for the Federation. The new president, former WNT star Cindy Parlow Cone, along with new CEO Will Wilson, pledged to overhaul the governing body’s relationship with its most successful team and work harder to find common ground.

There wasn’t much teeth to Biden’s threat. U.S. Soccer doesn’t receive federal funding for its national teams or other programs, and any public money that might support the staging of the 2026 World Cup would be related to the sort of spending that any big event would require, like local security. FIFA and U.S. Soccer executives met several times with members of President Donald Trump’s administration during the bidding process to secure the required visa and tax guarantees.

But the power of Biden’s message contributed to a public relations battle that U.S. Soccer knew it was losing, regardless of what happened in court. Parlow Cone and her colleagues are well aware that making things right isn’t just about the letter of the law.

“We want President Biden and all Americans to know that we are committed to equal pay and working together with our women’s national team players,” Parlow Cone said in a statement. “We’ve offered them the same compensation as the men’s national team for the games that we control, but haven’t been able to come to an agreement due to their requirement for us to pay the difference in FIFA World Cup prize money, which we don’t control.

“We’re doing everything we can to find a new way forward with our women’s national team players,” she added. “We truly want to work together, and our hope is we can meet soon to find a final resolution on this litigation. If we can come together and collaborate, we can have a much bigger impact in growing women’s soccer not only here in the United States, but across the world.”

Having a friend in the White House also means having someone who’s going to call you out and keep you honest.

"It feels good to know we have a supporter of soccer and our team in the White House,” Rapinoe said in a statement. “From the interactions I've had with him, I can tell he's a man of great empathy and has an innate drive to help people and do his best to try to heal this country. From the World Cups in 2015 to 2019 and his continued support of our fight for equality, we feel his support for our game and I'm hoping we can win something big so we can visit the White House.”

Preparation for the 2026 World Cup, which will take place in 16 cities across North America (including 10 in the U.S.), has been delayed by the pandemic. FIFA visits to potential host markets were postponed last year. Most of the help required from the federal government will be logistical, and Gulati, who still sits on the FIFA Council (the larger Executive Committee replacement), said most of it likely will be handled via an interagency coordinator—someone who can get the right person from Treasury or Homeland Security on the phone. Someone from Biden’s administration will fill that role.

“It’s not Biden sitting and negotiating what the tax rules are going to be,” Gulati explains. “That means him saying to the right people, ‘Hey, let’s get this done but don’t go overboard,’ or ‘Let’s get this done no matter what.’ ”

A number of people involved with the incoming administration have some connection to soccer, starting with chief of staff Ron Klain, who’s a friend of Gulati’s, a fan and the father of a former Harvard player. There’s confidence that World Cup organizers will have a sympathetic ear at the highest level.

“Ever since the bidding process for the FIFA World Cup 2026 began, the governments and member associations of Canada, Mexico and the USA have been extremely supportive in their eagerness to host what will be an amazing event for the whole world,” FIFA said in a written statement.

“The FIFA President would like to express his sincere congratulations to President-elect Joe Biden and would be honored to meet him at the earliest possible opportunity. As Mr. Biden is a soccer fan himself and someone who believes in the unique power of sport to bring people together, FIFA is greatly looking forward to a fruitful cooperation with Mr. Biden’s administration and to continue the excellent working relationship with the governments, member associations and local organizers of all three host countries.”

***

Beasley won’t be on the field in 2026. He finally retired at the end of the Houston Dynamo's 2019 MLS campaign and now, at 38, he’s working on bringing a USL League One (third tier) pro team to his hometown of Fort Wayne, Ind.

The coin is on a shelf at his home in Houston.

“After that, I put it in my house so I wouldn’t lose it. I stopped carrying it, now that I met Joe,” he says. “It had served its purpose. I don’t need to wait until I meet another official or military person. It served its purpose. Now it’s with my other memorabilia, safe and sound.”

He’s right. He doesn’t need the coin. Biden’s promise is right there on video. The only potential problem is that Biden is going to be pretty busy for at least the next four years, and Beasley isn’t yet sure how he’s going to collect the drink he's owed.

“I’ve got to win something so I can get to the White House,” he says. “I like tequila, so hopefully there’s some tequila in the Oval Office.”