A roundtable of stars at the core of the sport detail their experiences with racism, what it's like to be Black in America and their hopes and fears for the future.

The violent killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer and the ensuing protests across the country have propelled nationwide activism and amplification of Black voices. Over the last week and a half, people have entered a period of self-reflection, reading, talking and listening to the experiences of Black people in America. The conversations are new (and sometimes uncomfortable) and they are happening everywhere, including in a house of nine professional athletes training in Boulder, Colo., for next year’s Olympics.

“I’ve been able to share my experience, my fears and my hopes for the future with people who might not have had that conversation before,” says Aisha Praught-Leer, a middle distance runner who ran for the United States until 2015, when she switched to representing Jamaica. “Once that continues to grow, then we’ll have change, because Black people will have a voice in allies who want to change the dialogue and script for all Americans.”

There’s no question that Black track and field athletes are at the core of the sport and much of the reason why Team USA tops the medal table at global championships. But beyond stories of their successes as athletes, little has been shared or asked about their day-to-day life experiences and challenges when the color of their skin is seen as an obstacle.

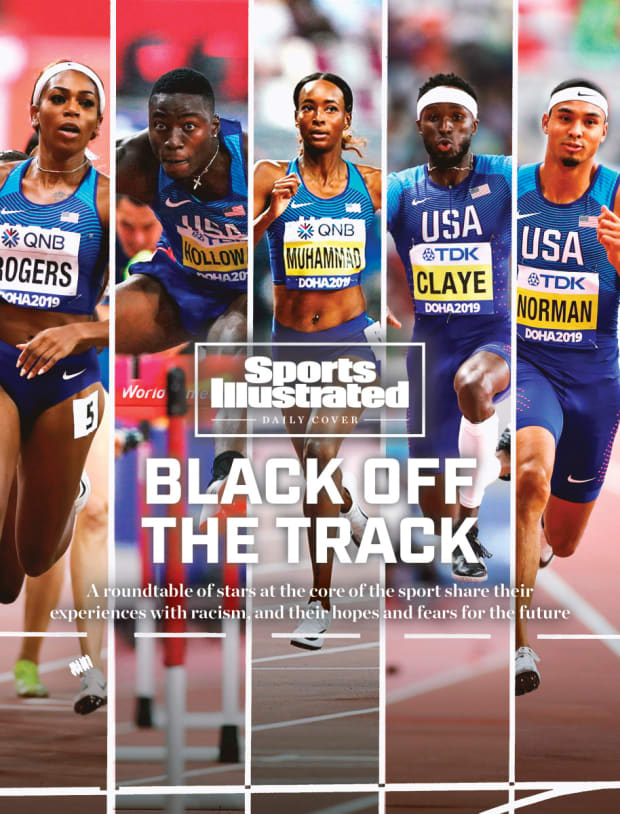

Last week, SI reached out to 14 Black track and field athletes, asked a series of three questions and listened. The participants included:

• Dalilah Muhammad, 400-meter hurdles world record holder, Olympic champion and world championship gold medalist

• Will Claye, 6x world championship medalist, 3x Olympic medalist

• Michael Norman, 2021 Olympic 400 meter gold favorite

• Mohammed Ahmed, 2019 world championship 5000 meter bronze medalist

• Grant Holloway, 2019 world championship 110-meter hurdles gold medalist

• Aleec Harris, 2017 U.S. 110-meter hurdles champion

• Shamier Little, 2015 400-meter hurdles world championship silver medalist

• Marielle Hall, long distance runner and 2016 Olympian

• Rai Benjamin, 2019 400-meter hurdles world championship silver medalist

• Aisha Praught-Leer, 2018 Commonwealth Games steeplechase gold medalist

• Darrell Hill, 2016 Olympian, shot put

• Raevyn Rogers, 2019 world championship 800-meter silver medalist

• Jarrion Lawson, 2017 world championship long jump silver medalist

• Keturah Orji, 2016 U.S. Olympian and triple jump U.S. record holder

The following responses have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What was your first or most impactful experience with racism that has shaped you into the person you are today?

Dalilah Muhammad: In 2019, I remember the night before the 400-meter hurdles world championship final in Doha, someone said to me that I had to win the race. He wasn’t speaking to me on the track and field side of it, he just wanted to make sure I knew that coming in second place would be completely unmarketable for me. Sometimes in America, that’s how it feels. You either have to be the best or we’re not spoken about. Being in second place is not a luxury that we have.

There have been many times I’ve been told I might have this or that if I was white. It’s such a widely accepted view and reality that we face as Black athletes or Black women. Whether it’s true or not, because it’s such a widely accepted view, you can’t help but recognize it as true. Those experiences are so difficult.

Marielle Hall: There are things that happened when I was younger that I missed. I’ve been in elementary school classes where someone doesn’t want me to play with their crowns because I’m dirty. Someone told my sister that she was never going to get married because she was Black. You have these small run-ins with racism but when you’re younger, you have ignorance. You get into the world and think everything is equal. Because so many of those early experiences are with your family, everyone is kind of loving in that setting. You’re not callused to other people yet.

Now, you think about those moments where your mom comes storming into your classroom yelling at the teacher or calling up someone’s parents to tell them what a kid said. I remember being overwhelmed because I’m still in class and I still want friends, so I didn’t want to be isolated. My mom has always been very brash but now that I’m older, I recognize that she was being protective. You want your kids to have the best possible experience and to be themselves in the best way that they can. You’re protective of those experiences because they are so formative. If you internalize the things that people say to you at a young age, that will show up in how you feel about yourself in the world and what you think you can do.

Mohammed Ahmed: During my time at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the Ferguson riots happened and they had an indelible impact on how I thought about my interaction with the police. I’ve only been stopped by the police once.

In 2016, my teammates and I went back to Madison to do some heat and humidity training before the Olympics in Rio. We were staying in Middleton, which is 15 to 20 minutes outside of Madison. I asked if I could take the car to State Street and reminisce some of my old days. I went and dined at my favorite restaurant and walked around. When it was time to go back, I took a glimpse of Camp Randall Stadium and my old neighborhood from my five years in the city. I pulled over and slowly drove through my neighborhood for 10 minutes or so. Then, I got on the road and left.

Within one or two minutes of being on the road, sirens start blaring. There were a number of cars near me and I figured it was for something that happened somewhere so I pulled over. All of a sudden, I saw the police officer come up right behind me.

I couldn’t believe it. I wondered if I did something wrong and Ferguson came to mind. I turned off the car, rolled down the window, put my hands up and didn’t say anything. I didn’t know how to interact with the police officer. I don’t think I was speeding but maybe I was five miles over the limit.

He asked me a number of questions, including, “What were you doing driving around that area?” So I determined he had been following me for at least 20 to 30 minutes. I felt like I had not broken any rules, but I remember I had trouble with the interaction—this was my first with an officer. At one point, he asked me if I was high or drunk. I said I wasn’t, but he said I seemed flustered.

I was reminded of Ferguson and I recalled in my mind what the police can do. He has a gun. That probably gave me anxiety and so I wasn’t able to speak or articulate as well as I could have. I was shocked to be pulled over like that, but I tried to compartmentalize things in a manner so nothing crazy would happen.

The experience that shaped me more than anything was being detained at the border. Visibly being a person of color, being Muslim, being a Somali and carrying a Muslim name—all of those identities went against me from a very young age. An Ethiopian-Canadian poet named Boonaa Mohammed, who is also Muslim and Black, says in one of his poems, “I’m black and Muslim, everywhere I go someone hates me.”

For me, I’ve had that experience based on my name, based on the war on terror and what that created. I can’t even count the number of times that I’ve been sent to the extra screening room at an airport. There’s also my color. I relate with that line in the poem a lot. Despite all the things I’ve accomplished as an athlete, I have to confront those two realities.

Will Claye: I’ve dealt with racism from when I was a child. Being called a n*****. Not getting opportunities that my white counterparts were given. Being reprimanded at school for things that I didn’t do. It’s always having that stigma on you. I can be a young Black man walking on the street and get harassed by the cops. If a white lady is walking, she goes to the other side of the street like I’m going to rob her.

There’s times when white men look at me, not even as a human being. I’ve always been a good athlete and so I’ve always been seen by white men like a horse. This is like horse racing and we’re a great breed. That’s how they looked at us as slaves 400 years ago. That’s not right.

I have been arrested for being Black. I have had guns pulled out on me in Arizona for being Black and going to a gas station. I’d be with my friends and the people who own the gas station called the police on us. When we walked outside, we had AK-47s pointed at us when we were 16 years old. I didn’t do anything. At that time, there wasn’t Instagram or a way to take a video, so it went unnoticed. To the Black community, when we see these situations, it feels like 9/11 each time it happens. It hurts. That’s why it’s come to this.

It’s something that we struggle with even today. I just got pulled over last week. A police officer asked me what I was doing in this type of car. I have a Mercedes-Benz and he wanted to know why we were driving in the area that we were driving in. He didn’t give us a ticket or anything, he just saw two Black people in a car and wanted to see what was going on. To me, that’s racial profiling. There were cars coming up and down that street but he chose to pull us over. I wasn’t speeding. I wasn’t doing anything wrong. That’s not right and that’s why we’ve lost trust in the law enforcement system and the government in general.

Grant Holloway: Where I live in Gainesville, Fla., is on the wealthier end of the city. Just last week, one family kept harassing me and asking, Do you live here? Who built your house? When did you buy your house? What’s your address? It was just because I’m a 22-year-old Black male. Instead of responding back, I just said, Have a nice day, and walked away. Racism comes in different ways—people think you can’t afford things because of the color of your skin or because you are 22 years old. It’s surprising that it’s still alive today, but it’s something that you need to have thick skin about and say, I’m going to be the bigger person in this situation.

Michael Norman: In middle school, I had a really good friend named Terrell. He was multi-racial, just like me—I am African American and Japanese, he is half-Filipino and half Black. But what made him different from me appearance-wise was that he had an Afro. My hair is relatively wavy and straight so I look a little more Pacific Islander. He had a whole Afro, which was pretty cool.

One day in the middle of the summer, we went to a gas station that was about a five-minute walk from my house in Murrieta, Calif. We went there to get Hot Cheetos, iced teas and stuff like that. It was normal kid stuff. I remember we looking for a specific type of Brisk or something. The cashier came up to us and asked Terrell to empty his pockets. I remember asking, “For what?” They thought we were stealing something, but he showed the cashier that there was nothing in his pockets. For me, that was the first time I was like, “Wow. People are really watching what we’re doing even though we’re 10-year-old kids in the gas station just trying to buy some iced tea.” I couldn’t believe people do this presumably because of our looks and because of his Afro. It was pretty upsetting at the time, but I don’t think I understood what it meant until I got older.

Aleec Harris: My first experience with racism was on some regular kid stuff. My friends and I got in a car and were going to McDonald’s in Stone Mountain, Ga. There were four of us and we were all Black. It was something we did all the time—just go out and get dollar sandwiches. We were coming back through the neighborhood one day and all of a sudden, we saw the police when we were leaving McDonald’s. They were following us, closed in and stopped us. But when they stopped us, it was all guns drawn at us. They told us to put our hands out of the windows. They were screaming. We were just trying to figure out why we were getting stopped from a McDonald’s run that we do all the time. I was like 13 or 14 at the time and sitting at the back seat of the driver. They didn’t give us a reason why we were getting pulled over. They finally let us out but put us in cuffs before they let us know why we were getting pulled over. They sat us all down and got everyone’s names. When we asked why, they told us that someone in the neighborhood had reported us for riding around and pointing guns out of the car. Clearly, there were no guns in the car and they ended up letting us go.

I didn’t even tell my parents because I was scared of my dad reacting. I felt bad and questioned whether I was wrong for riding around in the car with a group of friends who were Black. I had heard it growing up: we shouldn’t ride in a car together because we’re bound to get pulled over. That’s kind of weird because we’re just friends in a car doing nothing illegal, so why can’t you do that?

Rai Benjamin: My family’s friends have a house in Maine, so I spend a lot of time visiting there in the summer when I’m not running track. I remember walking around the streets of Portland to get some food at Five Guys. As I was exiting the store, this guy was coming in. He didn’t necessarily say “excuse me,” but I moved to the side just to be respectful. For me, it was no big deal. I’m from New York and people do that all the time and sometimes push our way in. As I walked out, he turned around and said “N*****.”

I was like, “What?” I know what he said but it didn’t necessarily register in my mind that he said that. I do this weird thing whenever I’m in a tough situation and I just start laughing. I laughed it off, but I stared at him for a while. He stared at me for a while. In that moment, anger built up and it was like, “What are you going to do about it?” I just came to my senses and thought that it wasn’t worth it.

Walking away from that hurt me a lot. The days passed. Months passed. In the moment and days that followed, I didn’t say anything. You just keep things to yourself. But I still couldn’t believe that happened. That was a game changer for me, and I still think about it today. As a Black man and Black people, we’re so used to compartmentalizing things like that. We don’t realize how traumatic that is. If you’re going out in public and someone is saying these derogatory terms to you, referring to you as property or drawing guns on you, that’s not normal at all. That’s not healthy and it’s something we’ve had to do for a really long time.

Shamier Little: Racism has always been in the background, shaping my life path. My most impactful encounter with racism was when I got called “n*****” for the third time. It is crazy because the first two times stunned me so much, that I could not really process how painful of a situation that was or how to even react. So I didn’t.

However, the third time I got called n***** was by an old white woman in Magnolia, Texas, as I was on my way back to school at College Station in April 2017. She scolded me for how I was driving. I was trying to take accountability for the situation and politely tried to dismiss her. She just took it up a notch and screamed, “You stupid f***ing n*****.” The situation got so blown out of proportion and the police got involved. I quickly walked up to the police officers because I was so anxious to explain what was going on. Now, I don’t even realize how much I could have put myself at danger.

I expected them to understand, mediate and hold the woman accountable for her actions, but all they did was see me as a threat and attempted to invalidate my experience. In response to my side of the story, one officer said something along the lines of, “I get called a pig all the time.”

At that moment, I stopped trying to make myself seen. Because to them, I was just another Black person and “n*****” was just another word. I went from feeling like I was easy to understand and empathize with, to feeling like people who do not look like me do not understand me. On top of that, they don’t give a damn about me. I realized that I had been moving through life being so naive and unaware of what it means to be Black in America.

Raevyn Rogers: On April 22, I was in my Philadelphia apartment, talking to my mom on the phone when the fire alarm was pulled. I heard some yelling and screaming outside my door and I looked through the peephole to see a woman talking to herself. I was a bit confused because we have a front desk person who was supposed to make residents aware about any intruders in the apartment complex, so I contacted the front desk, and they said to not go outside. (Don’t forget that your first instinct when a fire alarm is pulled is to leave. I’m glad I was able to at least look before I went out.)

The front desk told me that the police were on the way. In the meantime, the woman started spraying fire extinguishers everywhere in the hallway. The front desk woman told me she sent the police to my floor and to be on the lookout, because they should be there soon. I hear them on my floor and so I walk toward my door. A white police officer yells at me to open the door. When I open the door, he’s pointing a gun directly at me. I started screaming because my immediate reaction was to tell him that he has the wrong person. I’ve never been so scared in my life. I was also embarrassed because it was all men and I was shaking. Everything in me was shaking.

I don’t know what immediately drove this police officer to pull a gun without all of his facts together. He asked me, ‘Why aren’t you downstairs?’ And I explained to him that the lady was outside of my door and I couldn’t go downstairs. It was only after the gun was pulled that he started asking questions like, “What did she look like?” He didn’t know what she looked like but he comes in and points a gun at me in my own home?

There was no apology. Nothing. They never told me if the lady was arrested or apprehended that night. Hearing about George Floyd and reading about Breonna Taylor, it felt relevant to my situation—especially because Taylor died in her own home. It’s emotionally alive in me.

To you, what does it mean to be Black in America?

Will Claye: What is it like being a Black man in America? It’s a constant weight on your shoulders because you are at a disadvantage for everything and you’re already seen before you even open your mouth and take any action. You already have a stain on your resumé. What I have gone through has made me stronger because I’ve had to go through so much bulls***.

Darrell Hill: Being Black in America is to be loved as much as you can entertain. It is to be loved as much as you can dribble a ball. It is to be loved as well as you can catch a pass.

Being Black in America is to live inside of a box and systemically bound to that box. And then to be told, Look at how great you’re doing! Racism doesn’t exist. Things have come so far from the Civil Rights era. But at that point, still not be equal.

Being Black in America is driving on the highway at the speed limit while consciously looking at your rearview mirror, thinking that you might get pulled over by the police.

Being Black in America is being pulled over by the police and understanding you need to keep your hands visible at all times. It’s understanding that, at that moment, you may not make it home to your family.

Being Black in America is walking down the street and having white people cross when they see you. It’s watching people clench their purses as if you might try to harm or steal from them.

Being Black in America is walking past cars in a parking lot and hearing doors lock as if you were going to attempt to steal from their car.

I can go on for days. Unfortunately, that’s our reality. These are my real experiences.

Dalilah Muhammad: 2019 was an awakening year for me, personally. I witnessed injustices and inequalities in my life as a Black athlete, a Black woman and a Black runner in America. It’s almost difficult to put into words. I started to notice it for several reasons. For starters, I thought about how many times in my life I've been told that as a Black woman, I can’t be super emotional, and to be mindful of 100% of the things I’m saying during interviews. I’ve been told, don’t speak too loudly and don’t come across in any way that might convey a stereotype of an African American woman. For me, you live with these social injustices regularly and what became so apparent to me this year is how widely accepted they are. There are these rules that I must follow as a Black woman.

As a child, I don’t think I was very aware of it. As a kid you’re running and you’re enjoying what you do on a day-to-day basis. From first to sixth grade, I was one of three Black students in the entire school. My mother shipped me out to school from my all-Black neighborhood and that was my first encounter of a different world in an all-White school. I saw how different I was perceived in that school vs. how I was in my own neighborhood.

At that age, everyone is friends and I don’t have any stories of racism, but there’s an undertone of: You are different. I did really well in school. I had a lot of friends. I was good at sports and they liked me for that reason, but at the end of the day, there was always a difference between me and the children in that school. That was my first awareness of where I stood in America.

Mohammed Ahmed: Despite growing up in North America and having my education here during my formative years, I have a different identity given that I am a recent immigrant of color and from Africa. There is a different type of baggage that I have to carry. When I came to the United States, it was the first time that my Blackness was at the forefront of my identity. When you’re young, you’re probably not thinking too much about the system. You make sense of things as they come to you.

When I moved to Madison, Wisc., to attend the University of Wisconsin-Madison, that was the first time that race and color were at the core of my being. It was something that I had to confront, and it shook me a little bit. In many ways, Madison is a progressive city, as the population is fairly split between liberal and conservative political views, but it’s predominantly white. That made my experience as a Black man more severe and it magnified things. In class, I’d be the only person of color. For every single topic discussed pertaining to people of color, people would look to me. It got to the point where I would take it upon myself to represent my people. People expected that of me and so I tried shouldering it and it got to a point where it became super exhausting. It wasn’t just in the classroom.

You can really feel your Blackness. When I’d come across another person of color walking on campus, we’d both look at each other. We’d acknowledge each other and greet each other because there was a type of loneliness that both of us felt from living within that city and community.

Marielle Hall: Being Black in America is a very layered experience. That’s how I always looked at it. No one’s story is simple, but being Black and living in this country, there is something that’s compounded. It’s never just being a woman. It’s being a Black woman. It’s never being an athlete. It’s being a Black athlete. It’s never being a writer. It’s being a Black writer. I think that title follows you positively and negatively. I guess I have (sometimes maybe to my own detriment) just carried more than I feel my peers do. It is not necessarily a burden, because I do feel incredibly proud to be who I am and have the history of my family. But it does sometimes feel a little more complicated than I’d like it to be.

Aleec Harris: From my experience, being Black in America is being born a step behind everyone. I was born in hard conditions, so we didn’t have too many means to get by. I didn’t get to participate in many after school programs or camps or vacations. As you grow up and go through school, you start to hear of other kids’ experiences and the things they did growing up. I couldn’t relate because I didn’t grow up in that environment.

When I was high school, I was selling drugs, in a gang and in the streets because that was the environment around me. I went to a predominantly Black high school. All my friends had the same at-home experiences as me. We were poverty-stricken or in homes where their parents didn’t have certain opportunities or jobs.

Because I’m a step behind everyone, I had to work harder and I had to focus on my decision-making. It took me a while to understand that. After I came to that realization, then I started to focus on doing the right thing and trying to hustle and work hard at the things I believed and was good at.

Rai Benjamin: For me, being Black in America means you have to work 10 times as hard to get to wherever you want to be. The past has shown that although people have the opportunity to make it, that opportunity isn’t necessarily an easy road. Nothing is given to you. You have to go out, do it yourself and do it 10 times better than a white person. It means being judged whenever you step into a room.

Shamier Little: Being Black in America is daunting and exhausting. To be Black in America means that everywhere you go, everyone is aware of your presence. As a result, you are in a constant state of the unwarranted problems that your presence can bring. It is so tiring to live everyday being worried about your safety, simply because of the color of your skin.

Jarrion Lawson: Being Black entails a lot of things. You have to fight for every step that you take. You have to take the long route to success, because it feels like everyone and everything is against you. Being Black is working harder than others because you have a chip on your shoulder. It’s having to learn to be respectful and learn that you can’t say or do everything your white counterparts can. Being Black is being qualified and disqualified from things due to the color of your skin.

But, being Black is a privilege and an honor. All of the oppressions, trials and tribulations that we’ve had to go through for generations have made us smarter, stronger and wiser. We’ve become better. That can scare people but now we’re in positions of power that we weren’t able to occupy beforehand. We will continue to get better and that’s important to the success of this country.

Aisha Praught-Leer: The idea that I’ve been really grappling with in the past week is how for me, being Black in America is like living a double life. I have a very charmed, privileged and safe life on a day-to-day basis. This past week has me roiling under the surface because I can have an incredible day while training in a beautiful mountain town in Colorado, where everyone is happy, peaceful and there seems to be nothing wrong in the world. It’s a similar case for where I live in Boulder. The situations are pretty homogenous. You don’t really see what’s going on beyond your neighborhood. I’ll have a great day with training and then I’ll sink at night and realize that elsewhere, people who look like me are having a horrible time.

I almost get a sense of survivor’s guilt. What can I be doing so that other people who look like me have the same opportunity to be happy and peaceful? It’s difficult.

We came back to Minneapolis because my husband’s grandmother had her 92nd birthday. She’s struggling with some health issues, and as we decided to come back to celebrate what could be one of her last birthday parties, George Floyd was murdered. Coming here has been a very in-your-face version of the double life. While out in the suburbs with my husband’s family, you would never know that downtown is Ground Zero for what is now the greatest and largest civil rights movement in the world and in history. You would never know that something so vast and so large is growing just 18 minutes down the road. That’s kind of how my life is.

What are you doing and what do you hope other people can do to enact or encourage change in society?

Will Claye: I advocate that we go vote so we can change the people that are in power. The President is not doing anything to make the situation better to unify us. We’re not the ones that are going in and looting and doing all these things. We just want to change the system. The system has been against us for over 400 years. We want the system to allow us to live in America equally and to be treated equally in every sense of life.

Grant Holloway: I wouldn’t be surprised if in 2021, people don’t stand on the podium. It has gone through my head a couple times. If we’re able to run this year or next year, I’m warming up for every track meet in an “I Can’t Breathe” shirt. Every track meet. It’s just one of those things that you have to bring notice to. If I get fined, I’m gonna eat that cost. I know whatever I do will make a big impact because of the platform I have. You have to think of things and take the backlash that’s going to come with it.

Dalilah Muhammad: I have a lot of mixed emotions right now. I’m hurt by what I witnessed and watched with George Floyd. I’m heartbroken when I hear about the pure evilness of what’s going on. It hits so close to home often. But I also see a lot of good happening. I see a lot of people coming together. For that reason, I’m happy and thankful to see people fighting for the same cause. We need to recognize these injustices and make change.

I saw a quote earlier that said, “I’m no longer accepting the things I cannot change but changing the things I cannot accept.” I’m here for it. I’m grateful to see that most people are on the same page. I want people to not just make statements, but to back them up with true and real actions. I want to see things be less difficult for our next generations of Blacks and Black athletes. I want to see big outlets taking action to prevent such an injustice system.

Michael Norman: Personally, what I want to see from everybody is to be able to recognize microaggressions. Politely correct people for using them, even if they were consciously or unconsciously made. I think a big part of the problem is people let things go. Instead, people need to speak out and address the issue so it doesn’t continue to be an issue. Growing up, a lot of people would say, “Leave it alone. It’ll go away.” Enough is enough now.

Everybody has woken up and we can come together as a community to address this issue together. The first step is to have uncomfortable conversations with some people that may not feel like they have a voice or feel comfortable talking about it. Talk to them about it. You shouldn’t feel bad to speak up.

Mohammed Ahmed: There’s a level of educating and sharing our experiences that has some impact. People around me who are white or not Black are asking questions and I’m trying to answer them as much as I can. I’m trying to have as many of those conversations as I can.

However, if you look at the President, he’s just not helping. He’s just making white supremacists and racist people even more emboldened. He’s their puppet because he’s not really making any change or listening. Through the election, people can use their voices and their energy to knock this guy out and give America the opportunity to right its wrongs.

It also starts on the community level. If you’re a coach, how are you treating your people of color on your team? My former coach, Mick Byrne, called me and asked about my experience. He was asking for input on what can be created to have an impact on his student athletes.

What are universities doing to be more inclusive? Are they creating resources and meaningful dialogues with their people of color? Universities are a place of ideas so what ideas are we teaching our students and young people. Racists aren’t created in a vacuum and appear spontaneously. Children are conditioned and see what people are doing. They hear and they mimic and imbibe what people are saying.

Shamier Little: Now, as I watch the recent events unfold in person and across social media, I see that there is a revolution happening and I am watching my people come together. I am even more aware of my Blackness, but in a way that makes me so proud. I take pride in being Black and I wouldn't have it any other way.

I feel that people may know this, but I want people to recognize and audibly come to terms with the fact that Black people are talented. We are warm. We are strong. We are resilient. We are beautiful. We are magical and everything in between. We may bend, but we are never going to break.

Aleec Harris: I went to USC and I studied sociology. One of the things that was very impactful to me was reading statistics of social mobility, crime and human behavior. If you're born into poverty, the statistics of rising above that are so low and so hard. There’s Black-on-Black crime and that comes from poverty and the environment that you’re in. To be born Black in America, you have to deal with the poverty that you’re born into and once you make it out, you face things like police brutality. It’s a double-whammy. That was the shared experience that me and my friends had. We had to survive in this country with the least amount of resources.

I want people to know that it’s tough being born as a Black child. I’m fair-skinned and to be born as a darker child is hard. Our parents let us know that. Imagine growing up and your parents tell you that it’s going to be tough. You have to be more aware of your surroundings. Your mind may not be fully developed, but you need to be aware of your mind, your movements and where you’re at. That’s the experience of growing up Black. We are born with the odds against us.

Darrell Hill: I do feel that we are in a real time of change. ESPN’s Maria Taylor said, “I’ve never felt more emboldened to speak up and that I wouldn’t be reprimanded or feel repercussions for my statements than I do today.” That is the first step. We won’t be allowed to be shushed or pushed off any longer. I believe false change will not be accepted. Only true change will be accepted. I do feel positive that we’re entering a period of change.

It’s a time for action. The first thing is to communicate. Talk to one another—that goes for white people and Black people. White people in general have not lived the Black experience in this world. It’s up to them to be empathetic and open to listening. It’s up to us to share our experiences and where we’re coming from.

Acknowledge within yourself that there is a problem in this country. True change starts within every individual person internally. If we all understand that there’s a problem in this country, that’s the first step in making progress toward any type of change.

Vote. It sounds simple. Vote on the local level as well as the national level. As a country, we have to demand more from our politicians. We have to demand that they earn our votes by pushing laws that will change how the country is run inside and out. We can do surface changes that will put a blanket or band-aid on these issues that we have today. However, racism is so systematically rooted into our country, our laws and how the country is run. If we don’t come together and force these changes, we’re just kicking a can down the road and we’ll be addressing these problems in five years.

We can all support Black-owned businesses. We can disassociate ourselves from brands and companies who stand on racist principles or support those who do. That sounds simple, but unfortunately the only way people with money in this country understand anything is if you affect their bottom line.

Those are a lot of the things we can do as people to help us move forward. For a long time, we’ve felt like things wouldn’t change. This is the first time I can truthfully say, even though we’re in the middle of it and it can be heavy, I see now that there’s potential for change.

Marielle Hall: I’m trying to hold myself accountable. People don’t know if they’re hurting you if you don’t say something. Part of being in a competitive space, you don’t want to give people a leg up or admit things to yourself, because the mental side of sports does play tricks on you. Confronting all of this is hard. It means you have to go back to when you were in elementary and middle school and college. You feel like you’ve worked so hard to get to where you are. It’s hard to be reflective. It’s hard to hear about yourself or tell people about yourself. I’m trying to do the best I can to be honest with myself and the people around me. I can’t say I’ve completely flipped the switch and checked every person in the room or in my life, but I’m trying to realize there is accountability on all of us.

We just can’t be held up by our own hurt and anger. It’s all very valid but we want to keep the meter moving. It feels like a unique time. Some people’s responsibility in this will be to change. Some people’s responsibility in this will be to inform that change. That’s what I’m trying to put on myself.

Raevyn Rogers: Now is a good time for change. What stimulates change is being open to different perspectives. Once you have a set-in-stone perspective and you feel like your way is right, that will limit your growth and restrict you from being able to relate to other people. We endure a lot as Black people. A reason why so many people are enraged is because they look at multiple instances of violence and think that it could have been them. That’s what hurts the most.

I just hope that people can take this time of stillness—because we’re still in a pandemic, despite some places opening—to learn and be open to more perspectives.

Jarrion Lawson: I’ve spent the past week consuming the news and watching a lot of ESPN. I agree with something that Stephen A. Smith said on First Take about being happy that people are exposing themselves and how they really feel. It can be corrected so that for people who don’t know about the inequality or police brutality going on, we can educate you. Education is one of the most powerful weapons to transform society. I’m trying to do my part to educate my white friends and white people that I know. I want them to know that we’re children of God and human before you give us any other description. Hate is not natural. Love is.

Keturah Orji: There’s a lot everyone can do and a lot of information out there, so I just recommend finding out what works best for you and what you’re most comfortable with, as long as you’re furthering the cause. Olivia Baker and I have an Instagram Book Club where we invite followers to read with us for the month and discuss topics from a book we choose. For June we decided to read So You Want To Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo and it goes over topics like affirmative action, the n-word, cultural appropriation and police brutality. The best part of this book club is we are able to bring together a diverse group of people that are willing to discuss these difficult topics and challenge each other. We also want to do a Zoom call at the end of the month so we can go even more in depth on these topics. I’m excited about how our future conversations will go and the long term impact it will have on each person.

Aisha Praught-Leer: I got the chance to go to the George Floyd memorial today with my husband and his parents. I think what we’re seeing now is completely filling me with hope. That might not seem like the right thing to say because there has been so much sadness and destruction. Being at the memorial was breathtaking. The whole corner is sealed off from the public. There are volunteers everywhere. When you walk into the memorial area, there are signs that say, “This is a place of healing and hope.” You’re sprayed down in hand sanitizer and handed a mask if you don’t have one. You walk into this world that is almost like a utopian future of people who are totally different. There were all ages, genders, sexes, colors and creeds together healing, learning and growing.

I felt like in that moment, there will be change that comes from this. Hopefully, this isn’t just another headline that passes with the next news cycle and the next atrocity comes up. Being there was just so moving.

I took a picture of this sign that someone had written. It was just a little piece of paper among thousands of flowers and hundreds of other signs. It was someone’s simple writing that said, “I’m sorry we failed you. I vow to do more, more often—with more love—until there is justice and peace.” That’s how I feel and where I am.

In the last few years, I’ve been able to find my voice and speak up about things that aren’t right in the world. I’m finding hope that other people are feeling that way too. My hope for the rest of this movement is it keeps charging forward. I hope that people show up and vote in their city elections, state elections and the national election. That’s where I’m driving people—toward donating to moving forward in legislation, protections and foundations that provide opportunities for Black people to have the same opportunities that I had growing up and continue to enjoy. That’s the way forward. Everyone must stay engaged. Everybody has got to vote for the change that they want to see.