One of the most successful—and now controversial—trainers received a stark message: No one is bigger than Churchill Downs. But his presence still looms.

Barn 33 was ghostly quiet nine days before the 148th Kentucky Derby, nothing but naked lightbulbs and empty stalls. There were two pairs of shoes leaning against the wall in the shedrow, but no humans or horses were present. The blank beige wall by the entrance to what has been the mecca of the Churchill Downs stable area for a quarter century screamed a silent message:

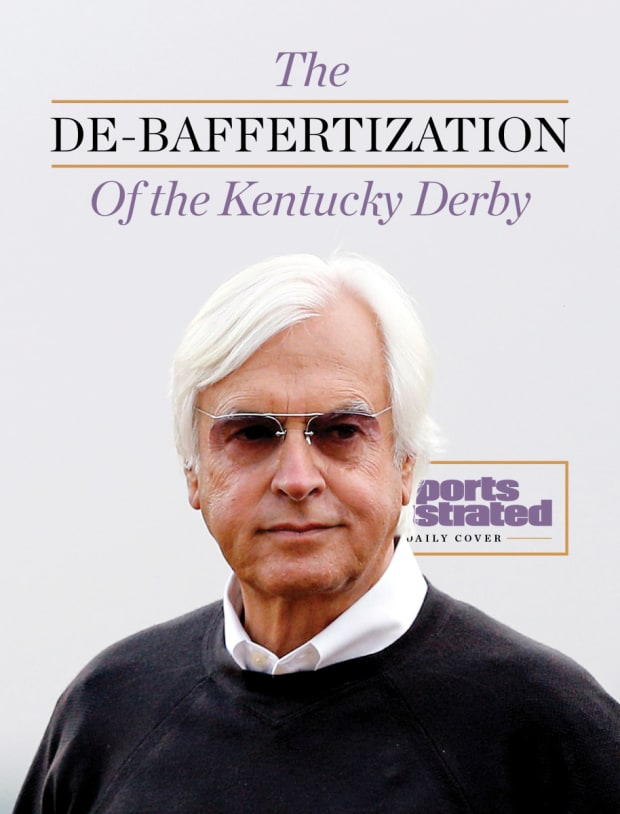

Bob Baffert is not here. Not welcome here. All but scrubbed from here.

The signs commemorating the white-haired trainer’s record-tying six Kentucky Derby wins and two Triple Crown triumphs are gone. The company line is that the racetrack took everything off the walls everywhere to repaint the barns during a renovation break last year—it was then up to the inhabitants of each barn to rehang them. With Baffert not around, the signs never went back up.

But Churchill had long enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with Baffert—he has been great for the Derby, and the Derby has been great for him. His barn was a constant stop on stable tours, and fans flocked in a dozen deep just to get a glimpse of his best horses or listen to the glib Californian’s steady stream of wisecracks. In happier times, track officials likely would have had those signs back on the Barn 33 wall the minute the paint dried.

Tom Pennington/Getty Images

That’s not all. On the second floor of the clubhouse, a partitioned area that had been labeled the Baffert Lounge is now the Ben A. Jones Lounge, named for the other winner of six Derbies. Baffert’s name and face can still be found on displays in the Derby Museum that honor Triple Crown winners American Pharoah and Justify, but that’s about it.

The de-Baffertization of Churchill is a stark reminder of his abrupt fall from grace and the bitter battle that has ensued between the most famous person and most famous venue in U.S. horse racing. When his record-breaking seventh Derby champion, Medina Spirit, was found to have failed a drug test after last year’s Run for the Roses, it set in motion a chain of events that resulted in Baffert’s two-year ban from Churchill Downs and Medina Spirit’s disqualification as the winner.

Lawsuits, calls to ban Baffert in states hosting other legs of the Triple Crown and inflamed rhetoric ensued. This was a bad breakup, and now it is the commanding story line of this year’s race. Bob Baffert vs. the Kentucky Derby has become the defining flashpoint in the sport’s ongoing struggle to properly medicate horses.

When the trainer’s last of many legal challenges to the Medina Spirit ruling was rebuffed in March, the owners of his top 3-year-old horses had no choice if they wanted to chase racing’s biggest prize—they had to move their colts to another trainer.

The beneficiary is the previously anonymous Tim Yakteen, a former Baffert assistant nearly two decades ago who was rarely involved with the barn’s top horses. Yakteen arrived here Sunday with three former Baffert trainees: Doppelganger, who is entered in a race on the Derby undercard; and Taiba and Messier, who both will try to win a Derby by proxy for arguably the greatest trainer in the history of this ancient sport.

“Messier and Taiba are phenomenal horses, and what matters most to me is that they get the opportunity to compete and win,” Baffert said in a written response to questions submitted by Sports Illustrated. “I can’t wait to cheer them on this Saturday.”

Baffert will cheer them on from afar, thousands of miles away. He’s been purged from the premises, and the trappings of his glory run have disappeared with him.

The only evidence that Baffert was ever in Barn 33 is a bumper sticker on a weathered, green office door that reads, “I like Kentucky-bred Roadster,” referring to one of Baffert’s more forgettable Derby entrants, the 15th-place finisher in the 2019 race.

Roadster. Rosebud?

The name and the sticker’s enigmatic presence as the last Baffert barn artifact conjure thoughts of the dying utterance from the lead character in the classic movie Citizen Kane. Weathering a scandal in exile, grandiose plutocrat Charles Foster Kane dies alone after saying the name of his childhood sled, which served as an emotional link to a more innocent time in his life.

The 2019 Triple Crown campaign was, for all intents and purposes, a more innocent time for Baffert—the last innocent time, if there is such a thing in a sport that has never been simon-pure, the final time Baffert worked without a cloud of suspicion hovering overhead.

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

That summer, The New York Times reported that his 2018 Triple Crown winner, Justify, failed a drug test after winning the Santa Anita Derby—the April race that set him up to become just the 13th horse in history to sweep the Derby, Preakness and Belmont Stakes. Justify’s positive test for an overage of scopolamine did not result in the horse’s DQ, which could have kept him out of the Kentucky Derby, and the positive test was not made public.

By the time Justify’s split sample had been tested—and also came back positive—the horse had already won the Derby. Still, news of the positive test remained out of the public eye. The California Horse Racing Board voted in August 2018 not to proceed with the scopolamine case against Baffert, citing other horses who had tested positive for the same substance (but below the legal racing limit) after ingesting what was believed to be a contaminated shipment of feed to Santa Anita. The feed contained naturally occurring jimson weed, which can trigger a positive test for scopolamine. Although the CHRB’s process was disturbingly opaque, its ruling to exonerate Justify and Baffert seemed, well, justifiable.

But that was only the beginning. Next came the May 2020 disqualifications in Arkansas for two standout Baffert 3-year-olds: a colt, Charlatan, who won the Arkansas Derby; and a filly, Gamine, who won an allowance race. Oaklawn Park said the two tested positive for an overage of the painkiller lidocaine. Baffert’s attorney in the case, W. Craig Robertson, argued the positive test was a result of Baffert assistant Jimmy Barnes’s wearing a medicated patch on his injured back that inadvertently transferred the lidocaine from the patch to his hands and ultimately to the horses.

It took nearly a year, but the Arkansas Racing Commission overturned the DQs of both horses and lifted a 15-day suspension for Baffert, though it imposed a fine of $10,000 for the trainer. Evidence presented to the ARC said Gamine had tested positive for 185 picograms of lidocaine and Charlatan for 46; the drug has a legal limit of 20 picograms. Robertson argued that measuring medication overages in such small amounts—a picogram is a trillionth of a gram—dramatically complicates a trainer’s job.

Before that appeal had been heard, Gamine had tested positive and been DQ’d from a second race—this time the 2020 Kentucky Oaks, in which she finished third as the heavy favorite in a race postponed to September by the COVID-19 pandemic. That positive test was for a race-day overage of the anti-inflammatory betamethasone (a medication that would haunt Baffert more several months later). Baffert said in an October 2020 statement that Gamine had legally been given betamethasone 18 days before the Oaks after being advised by veterinarians that it would be at an allowable limit in the horse’s system within 14 days.

That didn’t occur. Gamine’s DQ was upheld by the Kentucky Horse Racing Commission, and Baffert was fined again. A DQ in Churchill Downs’ second-biggest annual race was problematic. What happened next, in its biggest race, was catastrophic.

Pat McDonogh/Courier Journal

Eight days after Medina Spirit pulled off the 2021 Kentucky Derby upset at 12–1 odds, word erupted that the colt had failed the post-race drug test for an overage of betamethasone. Churchill quickly applied an indefinite suspension. Baffert originally said Medina Spirit had never been treated with the medication, then reversed course and said it was an ingredient in a topical ointment, not an injection, used to treat a rash. (Baffert and Medina Spirit’s owner, Amr Zedan, unsuccessfully argued the ointment created no competitive advantage and should not be ruled a violation.)

By then, many fans of the sport had grown weary of the recurring positive tests and explanations that all of this was simply bad luck, bad medicine or bad legislation. Baffert’s response to the Medina Spirit positive test was especially off-putting, not just in terms of cumulative doubt but also in defiant tone. In an interview with Dan Patrick, he declared himself a victim of “cancel culture” and criticized Churchill’s “knee-jerk” reaction.

(The Medina Spirit controversy deepened when the horse collapsed and died after a workout in December, though a necropsy did not reach a conclusive finding on cause of death. The Los Angeles Times previously had reported last October that Baffert had 75 horses die since 2000, either by racing, training, illness or in non-exercise accidents. Still, Baffert trainees were a small percentage of the spate of horse deaths that rocked Southern California racing in the last three years.)

Sports history is littered with forceful denials and fanciful excuses in the wake of positive drug tests, many of which did not age well. Horse racing has a drug history that dwarfs even cycling and track and field, not to mention a grisly track record of racetrack equine deaths. The sport’s reputation was further tarnished two years ago when the U.S. Attorney’s Office announced it had charged 27 people in an alleged “systematic, international scheme among trainers, vets and others to cheat using misbranded and adulterated drugs.” Among the allegations: that designer drugs could not be detected by standard testing.

Baffert was not implicated in that FBI investigation, and his attorneys have argued his career number of failed tests is low for a trainer who campaigns so many horses. Literature from a public-relations firm hired to work with Baffert and his attorneys declared his testing record “enviable” and said he is “at, or near, the very top echelon of medication rule compliance.” But the most successful trainers have long had to contend with an undercurrent of cynicism, and no one has been more successful than Baffert. That brings its own level of doubt beyond what the test results indicate.

Still, the benefit of the doubt is generally extended to horses that win the big races—as long as they test clean. Baffert found himself facing a spate of high-profile positives.

From jimson weed to a medicated patch to an injection timeline gone wrong to a surprisingly powerful ointment, his succession of explanations were not well received. Especially after Baffert pledged, in November 2020, “to do everything possible to ensure I receive no further medication complaints. … I want to raise the bar and set the standard for equine safety and rule compliance going forward.” (That comment came after another Baffert positive test, for Dextrorphan in the system of the horse Merneith, at Del Mar in July 2020. Attorney Robertson attributed that test result to a groom who was taking both DayQuil and NyQuil, which got into the horse’s system.)

Messing with the Run for the Roses is considered a mortal sin in racing, and Baffert had done exactly that. Medina Spirit became just the second medication DQ in the history of America’s oldest continuous sporting event. Even the biggest name and most recognizable figure in the sport had to face this truth, as delivered by Churchill Downs: No one is bigger than the Derby.

Churchill Downs Incorporated CEO Bill Carstanjen told Sports Illustrated that Kentucky’s race-day medication rules and Baffert’s test results were both unambiguous, and the trainer “was treated fairly. We were clear-eyed and rational and addressed the facts. We were disappointed that Bob didn’t take responsibility for his actions. I think this is one of those circumstances where there isn’t much controversy other than the rhetoric from Bob’s attorneys.”

Carstanjen used the words “cheat” or “cheater” three times in regard to Baffert in an interview. He bristled at the trainer’s attempts to deflect blame for the failed drug tests, saying Baffert issued “confusing and often ridiculous” explanations. “I think he embarrassed the entire industry and all of us felt we were being attacked.”

Baffert told SI he previously had a “good relationship” with Churchill and requests to meet with the track’s leadership “to resolve these issues” have not been reciprocated. A Churchill Downs spokesperson told SI that they had denied the request.Another Baffert attorney, Clark Brewster, provided SI with a more pointed response to Carstanjen: “What is perplexing and very damaging for the industry is that Churchill Downs would point to a commonly used and harmless topical ointment that no scientist says could have had an impact on a horse’s performance and call it ‘a medical overage.’ Churchill Downs is hopelessly conflicted and continues to be in denial of the truth and the facts.”

Given the varying levels of allowable medication and sanctions applied to trainers or jockeys in Arkansas doesn't necessarily apply in California, the Horse Racing Integrity and Safety Authority (HISA) was created by Congress in December 2020 in an attempt to more uniformly regulate the sport. HISA's racetrack safety rules take effect July 1, and the authority is working with Drug Free Sport International to establish a Horse Racing Integrity and Welfare Unit that oversees medication education and enforcement. Churchill Downs is among the entities backing HISA. "Currently, medication is really balkanized and handled state by state," Carstanjen said.. "We're big proponents of a national approach."

"For far too long, Bob Baffert's scandals have completely engulfed and overshadowed the so-called 'Sport of Kings,'” says Marty Irby, executive director of the watchdog group Animal Wellness Action. “If Baffert truly wants thoroughbred horse racing to continue to be defined as a legitimate American sport, then he'll step aside until his suspension is over and allow other trainers, breeders, owners and jockeys the opportunity to enjoy a clean Triple Crown without his controversy in 2022."

Given the adversarial positions, it’s reasonable to assume Churchill would prefer someone other than Messier or Taiba to win the Derby and provide Baffert secondhand validation. Because if you ask almost anyone in the game, that would be the inference drawn.

“They’re still Bob’s horses,” said Hall of Fame trainer D. Wayne Lukas, himself a four-time Derby winner whose relationship with Baffert has evolved from adversarial to amiable across 25 years. Added fellow trainer Norm Casse: “Even when he’s not involved, he’s involved.”

Andy Lyons/Getty Images

The van bringing his horses to the Churchill stable area was running late, so Tim Yakteen took a brief walk from Barn 37 to the backstretch railing. There was a Sunday silence at the ancient edifice; the morning training hours were long over and there were no races that sunny afternoon. The giant grandstand stood empty. The only things stirring were birds in the trees and flags rippling in a stiff breeze.

Dressed in his characteristic barn attire—blue jeans, a pressed blue dress shirt and a baseball cap—the 57-year-old Yakteen strode up to the gap in the backstretch where horses can enter the track from the stable area. He was alone. Yakteen placed his hands on his hips, glancing right and left and straight ahead.

If this nobody trainer wins the Derby with a horse he inherited six weeks before the race, a dramatized version of that scene will be in the inevitable movie. The place where Yakteen stood offers arguably the best view of the fabled Twin Spires and, in the film, he would certainly linger there to take in the scene and contemplate what fate has put in his hands.

The reality was decidedly less poignant. That glimpse of the Spires was brief and businesslike.

“I had time to kill; it’s a beautiful day,” Yakteen said with a chuckle. “I just wanted to get a look at the racing surface.”

Still, the moment did carry some symbolic freight. Yakteen didn’t know it, but he alighted precisely where Baffert had stood many times over the years. Baffert always drove around to the Churchill front side when his horses recorded major breezes, but on mornings when a routine jog or gallop was on the work tab, that rail gap was where he watched many of them. Yakteen was, literally, following in Baffert’s famous footsteps.

Can he follow those footsteps around to the winner’s circle on the front side of the track Saturday? It’s a dizzying proposition. Yakteen has been an assistant to a pair of Hall of Famers in Baffert and the late Charlie Whittingham and has been training on his own since 2004, but he’s never come close to saddling a Derby horse before now. “Since going out on my own, these would be the best 3-year-olds in my career,” Yakteen said.

He’s had some nice moments prior to inheriting Baffert’s stars: 10 graded stakes victories, three of them Grade Is. Most of those came with two big horses: Mucho Unusual and Points Offthebench, the latter earning the 2013 Eclipse Award as the nation’s champion sprinter. But in a sport that gains significant mainstream attention only during the spring Triple Crown series and autumn Breeders’ Cup, Yakteen has been invisible.

Scour the internet for stories about him and the returns are slim. But an interesting one pops up from July 2021: about a fight Yakteen had with fellow trainer Richard Baltas at Santa Anita, which reportedly stemmed from an argument in the wake of the Arkansas Racing Commission’s ruling on Baffert’s ’20 medication violations there. According to a Los Angeles Times story, Baltas was “bad-mouthing” Baffert and “Yakteen came to his defense, verbally and physically.” Both trainers were fined for the altercation.

Andy Lyons/Getty Images

Logic dictates that Yakteen’s loyalty to Baffert played an important role in being chosen to inherit Taiba and Messier (not to mention inheriting exercise rider Humberto Gomez, who rode Justify in the mornings in 2018). Tom Ryan, bloodstock and racing manager for Messier owner SF Racing, also had logistical reasons for the decision to tab Yakteen: “It made sense to keep them in the same surroundings—California, same racetrack. If you send them to Florida, they have to adapt to the water, adapt to the hay, adapt to more things. And Tim is a very good horseman.”

Although there is nothing in the rules—in California or Kentucky—that prohibit consultation and communication with Baffert, Yakteen said the two have not talked since the horses changed hands. Even if they haven’t spoken, it wouldn’t be hard for a former assistant to replicate Baffert’s customary training pattern for horses leading up to the Kentucky Derby. But it is noteworthy that Yakteen has not followed the usual route with Taiba, a $1.7 million purchase.

The powerful chestnut colt might be the most unseasoned Derby runner ever, running just two career races and somewhat ominously landing on the Santa Anita “vet’s list” after winning his debut in early March. That means veterinarians had a physical concern about Taiba, who is owned by the owner of Medina Spirit, Amr Zedan. Taiba was listed as “unsound,” indicating a likely leg issue. According to Santa Anita blogger Jeff Siegel, who was there, jockey John Velazquez eased the horse up quickly after the race and walked him slowly back to the winner’s circle. At the time, Baffert told Siegel, “Johnny thought he felt something funny behind, so he pulled him up. By the time he got back to the winner’s circle, the colt was fine. I don’t know if he was put on the vet’s list, but it was nothing.”

Once on the vet’s list in California, Taiba had to wait seven days before recording any timed workout and 15 days before an official workout (which is different from any timed work, per the California Horse Racing Board’s Mike Marten). Taiba also had to pass pre- and post-work vet examinations, meet a minimum time standard and submit to post-work sample testing.

Taiba returned to the work tab March 18 and recorded three official workouts before surprisingly entering the Santa Anita Derby off one career start, then more surprisingly winning it by passing Messier in the stretch and pulling away. That punched his ticket to Louisville, but Yakteen has worked him only once since that race, 19 days later and nine days before the Derby.

Baffert customarily works his horses hard and has them dead fit for big races. Yakteen has taken a different approach, putting a lightly raced and lightly conditioned colt into a 20-horse alley fight. It’s a bold deviation. “I wanted to make sure I was bringing a horse to Kentucky with a full tank,” he says. “It would do me no good to take a horse that I misread to Churchill and have him underperform because I over-trained him.”

Yakteen is finding out what it’s like to have his every decision scrutinized on a grand scale. When 15–20 media members huddled around him outside Barn 37 on Monday morning for their first chance to talk to the trainer since he got to Louisville, Yakteen disarmingly reached for his phone and shot a quick video of the throng. “My boys will never believe this,” the father of two said before taking questions and providing clipped, sometimes nervous answers.

He’s inexperienced in these settings, but not unaware of the story he’s become. The gravity of the moment and oddity of the situation is not lost on a guy who has made a living at the racetrack without getting rich there. This could be viewed as an incredible opportunity or a heavy burden, or both.

“I’ve sort of had a lottery ticket dropped in my lap,” Yakteen said. “I’m trying to go to the window and cash it.”

One of the standing displays in the Derby Museum is a statue of a horse with a jockey on its back and the garland of roses draped over its withers. Each year, they change the silks of the jockey and the words on the horse’s saddle cloth to correspond with the new winner.

This year, Churchill had to invent a scene.

Mandaloun, winner of the 2021 Kentucky Derby by disqualification, never got to wear the roses. Never stood in the winner’s circle. Never was feted publicly as the winner of America’s biggest horse race. But the statue says otherwise, with historical accuracy taking a back seat to museum continuity.

Trainer Brad Cox was in his home in New Orleans, packing to go to a race in Saudi Arabia, when his phone started blowing up with texts. They were from media members informing him that he had just won the Derby. Months after the fact, the DQ of Medina Spirit was made official and Mandaloun was elevated to the top spot.

Pat McDonogh / Courier Journal via Imagn Content Services

“It just really wasn’t any thrill of victory,” Cox said. “It was just, ‘O.K., cool. It is what it is.’ It didn’t have that feel to it. It’s the end of a long, drawn-out deal that’s unfortunate. Maybe something good comes from it—maybe pre-race testing instead of post-race testing, that’s my biggest thing. A race of this magnitude, we should know when the horses go over there that we’re all playing on a level playing field and we don’t have to worry about a result a week later.”

The debacle of 2021 casts a shadow over the 2022 Kentucky Derby. Bob Baffert is just a spectral non-presence this time around, but his absence is felt—all the more so if one of his former horses wins the race.

As for the future? One of the questions SI submitted to Baffert was about a possible return to the Derby after his suspension is served. His written response: “The only thing I’m fighting for is to overturn this unfair suspension because I want to keep doing what I love, which is to train horses and compete. I have every confidence that, when my case gets before a neutral judge, the court will see that the facts and the law have been with me the whole time.”

If there is any doubt about the 69-year-old Baffert’s future intentions, consider this: Just two weeks ago, he and bloodstock agent Gary Young entered a winning bid of $2.3 million for a 2-year-old colt in Ocala, Fla., on behalf of Zedan, the owner of Medina Spirit and Taiba. That’s a big number, and a clear signal.

Bob Baffert has no intention of leaving the sport, and every intention of trying to win its biggest races again—including the Kentucky Derby, where he has been scrubbed from existence.