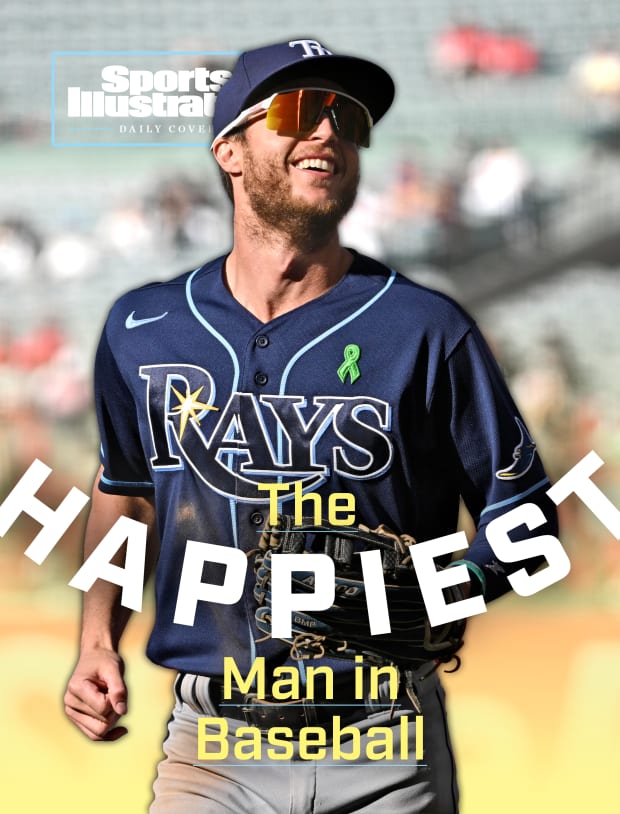

The Rays outfielder is on a mission to make sure we don’t lose sight of what makes this game great.

The Rays have won more than any other team in the American League over the last three seasons. But in the event that they do find themselves losing—if they find themselves losing by a lot—there is no question as to what will come next. It will be time for outfielder Brett Phillips to pitch.

A certain skill set is required for a position player to become The Guy Who Pitches in a Blowout. It doesn’t matter if he has any talent for pitching. (It’s preferable if he doesn’t.) What matters instead is his comedic timing. He cannot take himself too seriously: He has to recognize this is all kind of a joke, and, more than that, he has to show that he knows precisely when to laugh. Yet he still has to make an effort: A position player on the mound is a joke, after all, but it can’t be a farce. He has to be willing to look silly but unwilling to just mail it in. He has to have fun. It is easy to find a guy who can do this once—who can’t volunteer himself for this particular brand of fun just once?—but it is much harder to find someone who can do it whenever it’s needed, no matter how bad the loss or how sour the mood, and do it with a consistent sense of joy.

Which means there isn’t a player right now who is better suited to the job than Phillips.

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated

That shouldn’t be much of a surprise to anyone who has seen him do … anything. The 27-year-old is seemingly always having the time of his life. If he’s hit by a pitch, he’ll turn it into a laughing matter. If he’s left off a playoff roster, he’ll become an elite cheerleader in the dugout. If he hits a routine home run, he’ll sprint at full speed around the bases, just because he can, and if he hits a walk-off in the World Series, he’ll do much more than that. And, of course, if he’s asked to pitch, he’ll lay out for a ridiculous catch in foul territory despite being down by double digits, or he’ll create an environment so fun that the batter has no choice but to lean into it. There are some players who make baseball feel like a science or a craft or an art. Phillips makes it feel like a game and, in turn, makes that feel like its highest and best function.

For him, it’s simple: Phillips believes baseball is fun. It’s a statement he has made into a personal brand—he now emblazons shirts with the sentence to spread the message. It might sound almost too obvious to be worth repeating: Sure, of course, baseball is fun. But at a time where the game is increasingly consumed with existential questions about its rules, its labor relations and its appeal as an entertainment product, the reminder doesn’t hurt. And Phillips himself knows how easy it can be to forget: A player who spent his early years bouncing from one organization to another with plenty of experience on the bench is not exactly the most obvious choice to embrace all that can make a baseball career fun. But he doesn’t want to lose sight of it. Now in his third season with the Rays—the same team he rooted for as a boy growing up 20 minutes away in Seminole, Fla.—Phillips couldn’t be happier.

Even when, say, looking silly on the mound in a blowout loss.

“What else would I be doing?” Phillips grins. “Like, I’m a Major League Baseball player for my hometown. If we're down 10 runs, and I'm asked to go pitch, I’m going to. It's fun. I'm playing baseball.”

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated

The first thing Phillips’s teammates will say about him is that, yes, he’s really like this all the time. The guy who is an unfailing source of energy on the field is the same in the dugout, on the plane, in the clubhouse. He never stops. Even the iconic braying laugh—Phillips’s first viral baseball moment, when he was a minor leaguer with the Brewers in 2016, was a video of him dissolving into hysterics—nothing about that is played up, either. (“I’d never seen anything like it,” Rays outfielder Kevin Kiermaier says of Phillips’s laugh. “But it’s real.”) Whether he’s in the starting lineup or on the bench, succeeding or slumping, this is Phillips—always the happiest guy in the room.

“At this level, especially, there's a lot of stress. There's a lot of reminders that it's a business. Someone like Brett is a constant reminder that it’s a game,” says Rays president of baseball operations Erik Neander. “And he’s a constant reminder to just be grateful.”

If the first thing teammates will say about him is that the energy is real, the second is that the gratitude is, too: He’s actively thankful for everything. Kiermaier remembers approaching Phillips’s locker right after he was traded to the Rays, in August 2020, to give him the standard welcome from a veteran: nice to have you, this is how we do things around here, ask if you need anything. It was nothing special. But Kiermaier was taken by how appreciative Phillips was—how sincerely he thanked his new teammate for something as simple as a quick chat. Kiermaier had walked maybe 15 feet through the clubhouse to talk for a few minutes. Phillips reacted as effusively as if he’d crossed the ocean to hand-deliver a gift.

“He just appreciates everything so much,” Kiermaier says. “I knew he was going to be perfect right then and there.”

That gratitude holds even when he doesn’t have an opportunity to play. His signature playoff moment is, of course, his walk-off hit from Game 4 of the 2020 World Series. But that came after he’d been left off the original postseason roster earlier that year, just as he would be for the ALDS in ‘21, and he embraced those opportunities with the same zeal: Happy to have a chance to help the team however he could, he grabbed a clipboard and started writing down inspirational messages as a coach.

“Honestly, that one still sticks out to me, because it not only hits on how much energy that he brings, but the selflessness,” says Rays second baseman Brandon Lowe. “He could have easily gone back to the hotel or just sat in the back of the dugout or the clubhouse and not done anything. … But he understood that if he wasn’t going to be able to do it on the field, he’d do something in the dugout.”

Greg Nelson/Sports Illustrated

It’s not that Phillips doesn’t take baseball seriously. Rather, it’s the opposite. He knows exactly how much the game means—to him and to his teammates and to everyone watching. He just doesn’t want to let himself lose sight of the fact that it is still, in all of that, a game.

That was a conscious choice he made while in the minors. Drafted by the Astros out of high school in 2012, as he worked through the grinder of the minor leagues, he saw how easy it could be to buckle under the pressure of baseball as a career. He watched teammates lose their sense of self as they slumped or even got released. And as he started to struggle at times himself, trying to find a path to the majors, he landed on a revelation of sorts: All he’d ever dreamed of was playing baseball. He’d dreamed of it precisely because of the fun it had created for him, ever since he was a little kid, and he didn’t want to lose that just as he got to the top.

“I want to win just as much as everyone else,” Phillips says. “But at the end of the day—all I can do is control what I can control. And that’s the work I put in, how I treat people, and ultimately, how I have fun. And after all of that, if you really think about it, it's out of your control.”

He can’t determine the outcome of all his efforts. (Though he can certainly determine how much he puts in: “You can’t just be the goofy, fun-loving guy and not produce, right?” he says. “Like, it’s still a multibillion dollar industry. There’s pressure to perform.”) But he can make sure that he’s enjoying what’s in front of him. This is what he’s tried to keep central, as he was traded from the Astros’ organization to the Brewers to the Royals to, finally, his hometown Rays: This is our job, yes, but it’s also an incredible gift. Sometimes he can make that evident in his play on the field. Other times, it’s on the bench or in the clubhouse. But he never wants to go a day without embracing it—for himself and for everyone around him.

“For me personally, someone who’s kind of struggled with the mental aspects of staying excited for the game … keeping it light is huge,” says Rays reliever Andrew Kittredge. “And he just does a good job of making sure everyone’s having fun.”

That applies to those outside the clubhouse, too. Like during a game in April, when the first pitch was thrown out by a local 8-year-old girl named Chloe Grimes, who had cancer once as a toddler and was diagnosed with the illness for a second time this year. The Rays broadcast visited her in the stands during the third inning. Asked for her favorite player, she pointed to Phillips, who was at the plate.

Almost as soon as she said his name, he hit a home run.

Phillips made sure the ball was retrieved from the catwalk at Tropicana Field so that he could sign it and bring it to Grimes. He helped arrange for her medical bills to be paid through his Baseball Is Fun brand and the Rays Community Fund. The Grimes family was moved by the generosity, says Chloe’s mother, Jacquie—but never more so than when Phillips came to visit Chloe at home. He gave her the ball and took a photo. And then he stuck around.

He asked her how she wanted to spend the afternoon. She explained that her favorite thing to play with right now was the karaoke machine she had in her bedroom. Perfect, Phillips said. The next hour was devoted to a dance party, going over all her favorite songs, even making her laugh with a springtime version of “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.”

It’s only solidified him as her favorite player. (“Brett Phillips was in my room,” the third-grader repeats reverently, weeks later.) But she didn’t have any doubts about that to begin with. Why?

“Because,” Grimes says. “He’s always smiling. He’s fun.”

Courtesy of Jacquie Grimes

Phillips’s wife, Bri, is unusually well-equipped to understand the sport as a career: Her father, Trey Hillman, is a baseball lifer—the only man ever to manage in MLB, Japan’s NPB and Korea’s KBO. That gave Bri plenty of insight into all that can make professional baseball challenging. It gave her somewhat less so on all that could make it fun.

“I liked baseball,” she says of her original relationship to the sport. “I wasn’t in love with baseball. … But when I started dating Brett, I told my mom, like, wow, I have this whole new appreciation for the game.”

The couple met when Phillips was in the Astros’ system and Hillman was a bench coach for the big-league club. Bri made a spring training visit with her family, and they briefly met Phillips, who was playing in his first big league spring game.

He got one plate appearance. It was a home run. Afterward, Bri’s mother and aunt encouraged her to go take a picture with the nice young player they’d chatted with earlier who’d ended up homering. She thought little of it. But he was immediately smitten, and when she reached out later to send him the picture over Twitter, the two hit it off.

To date a coach’s daughter would be intimidating no matter the context—but especially given that Hillman was a major league coach while Phillips was going to start the season down in High A. He wasn’t sure if it would fly. So as he continued to talk to Bri, he settled on a plan that seemed a bit more promising: When I get promoted to Double A, could I ask your father for permission to take you on a date? Bri said she’d like that. And sure enough, when Phillips was called up to join the Corpus Christi Hooks at the All-Star break, one of his first calls was to the big league bench coach he hadn’t talked to since spring training.

“I was so scared,” Phillips says. “It was probably just 10 seconds of silence, but it felt like forever.” Finally, Hillman gave him an answer: Sure. But my giving my blessing doesn’t mean she’s actually going to like you.

Courtesy of Bri Phillips

So Bri went down to Corpus Christi. Their first date was at the Texas State Aquarium, followed by a trip to Whataburger, and despite her father’s joking warning, she actually did like him. They’ve now been married for two and a half years.

That means Phillips—with his new-school embrace of fun—has a father-in-law with a more traditional handle on the game. (Hillman is now a player development staff coach with the Angels.) But he’s grateful for the perspective.

“I have the utmost respect for that man in the world,” Phillips says. “If I need any advice, or if I have any questions, I know I’m going to get the best answer, the best wisdom and information from him, because of how well respected he is in this industry.”

Like, for instance, when Phillips hit a walk-off home run last September against the Tigers. He pulled out all the stops to celebrate—bat flip, signature airplane windmilling around the bases, jumping up and grabbing the netting behind home plate to enjoy the moment with the fans. But he later asked his father-in-law: Was that too much? Hillman didn’t tell him that he shouldn’t have celebrated. But he encouraged him to consider how going that hard might have made the opposing pitcher feel. It made Phillips think.

“I never want to make someone feel less about themselves,” he says. “So would I bat-flip again? Yes. Would I airplane around the bases? Yes. Would I jump off WWE-style? Probably not.”

That’s the balance Phillips wants to strike—to play with emotion that lifts people up without letting anybody down. (It’s what he wants off the field, too: “People do ask me that,” Bri says. “They’re like, is he like this at home? But he is. There’s never an experience where he’s not happy. He just loves life.”) He simply wants to share the joy he feels—with teammates and fans and strangers alike.

Earlier this season, when the Rays invited children in attendance to run the bases after a Sunday afternoon game, Phillips stuck around. He remembered running the bases as a kid at the Trop himself—he first visited the stadium more than a year before the Rays played their first game there to attend a fan fest with his grandmother in 1996—and as he watched a new generation enjoy exactly what he had two decades before, exactly what he enjoys as an adult now, he felt he had no choice. He jumped in and ran with them.

Why? There could be only one answer: Baseball is fun.

More MLB Coverage:

• Mookie Betts Is Back in MVP Form

• The Twins Are Teaching MLB Teams How to Avoid a Teardown

• Lessons of a Life Well Lived: My Friendship With Roger Angell

• Nobody Did It Better Than Roger Angell

• MLB Power Rankings: Dodgers, Yankees Flip-Flop at the Top