The U.S.'s Leadership Council has supplanted a more typical captaincy, with the matchday armband rotating throughout Gregg Berhalter's tenure as coach.

It was departure time, and Gregg Berhalter had a problem—one of those common-in-theory, but not-so-common-in-practice problems that creates an extra headache for a coach on game day. The U.S. men's national team’s bus was ready to depart for the stadium, and not everyone had made it. It would leave the hotel minus a starter.

"This player’s still in his room. There was a secondary vehicle that was leaving that held up for him,” Berhalter recalled. “As we’re en route, this player eventually gets in the secondary vehicle, comes to the game, and he was going to be a starter in the game. So now, as we’re on the bus I'm thinking to myself, ‘Who are we preparing to start this game?’ We know he’s en route, but we may not be comfortable playing this guy.”

Berhalter omitted the details of who, when and where, in part because it’s an internal team matter and in part because this is a story about process, not particulars. Berhalter’s U.S. team, as young and as promising as it may be, is far from a finished product. It’s on a trajectory. And that helps inform decisions like the one made that day, ahead of what the manager called “a big game.”

No team is a true democracy. Ultimately, the buck has to stop with one person. But this new U.S. national team has a far more diffuse and diverse leadership structure than most. Growth results from empowerment, and from day one, Berhalter has endeavored to establish a system and culture that encourages players to “take ownership” of their international experience. As a result, more than two years into Berhalter’s tenure, there still is no official and permanent national team captain. And there are no plans to appoint one.

Instead, there’s the Leadership Council, a group of six players elected by their peers who consult with Berhalter on issues big and small. The Council acts as a conduit between coaches and players, and as a vehicle to empower emerging U.S. leaders. Established as a permanent fixture in the fall of 2019, it represents a noteworthy approach in world football, as well as the end of a long line of established, big-name U.S. captains, from Claudio Reyna and Carlos Bocanegra to Clint Dempsey and Michael Bradley.

On the day of the “big game,” the Leadership Council was called into action.

"If I didn’t know the feelings of the group, I could’ve made a decision that could’ve negatively impacted the team,” Berhalter told Sports Illustrated ahead of this week’s friendlies against Jamaica and Northern Ireland. “I could’ve played him and they would’ve been pissed off. I could’ve not played him and they could’ve thought he would’ve helped the team. So, it was really vital for me to get the feelings of the group and the Leadership Council provided that, and I think that’s an example of it working at its finest.”

They met at the stadium. Berhalter posed the problem to the Council, who discussed it, weighed the options and decided they were were comfortable with the tardy player taking the field.

“This player played and played a great game, and after [he] apologized for coming late,” Berhalter said.

“The personnel may change, but the environment doesn’t change,” he added. “We want players to take ownership. We want them to be involved in the decision making process, and regardless of who’s in camp, that's going to be the case. They’ll be included. There will be responsibilities. They’ll have to show leadership skills and communication skills to help come up with decisions that will guide the team.”

Berhalter knows a bit about team leadership himself, having served as a captain while playing in Germany for Energie Cottbus and 1860 Munich and in MLS for the LA Galaxy. He said it makes sense in a club environment—where the same players spend every day together and where there’s likely a range of ages and experience—for a single captain take center stage. It formalizes an existing leadership and seniority structure, makes navigating a long season a bit more seamless and establishes a consistent spokesperson and figurehead for media and supporters.

But national teams are different. Gatherings are intermittent and inconsistent, and player turnover is high. What happens, especially on a younger squad, if the captain misses significant time? Take Christian Pulisic, for example. Many think he’s Berhalter’s most talented player, and he has the most international seasoning among the young U.S. core. That might make him a good choice for captain. But Pulisic hasn’t worn a U.S. jersey in 16 months. He hasn’t had the chance to lead.

The idea for the Leadership Council took shape when Berhalter was coaching the Columbus Crew and had a younger captain in Wil Trapp.

“We created a council and saw that worked really well, so he didn’t have the burden of decisions laying solely on his shoulders. He was able to share that with some older guys who helped push him and helped him develop as a leader,” Berhalter said.

“Then when I looked at the national team, we’ve got six Wils,” he continued. “We’ve got really young guys here and they definitely have leadership capacity and abilities, and now we want to help develop them.”

It was Berhalter’s intention from the start to do away with the permanent captain. At his first camp in January 2019, he informed Bradley of the decision.

“It was great. It was really up front,” Berhalter said of the conversation with the veteran midfielder. “We said 'Listen, we value what you bring to the team, and here’s how we’re going to do it moving forward.’ I’ve probably been quoted 100 times talking about veteran leadership, how valuable it is. And that’s why there’s veterans on the Leadership Council and Michael, when he was in the team, was certainly in the Leadership Council.”

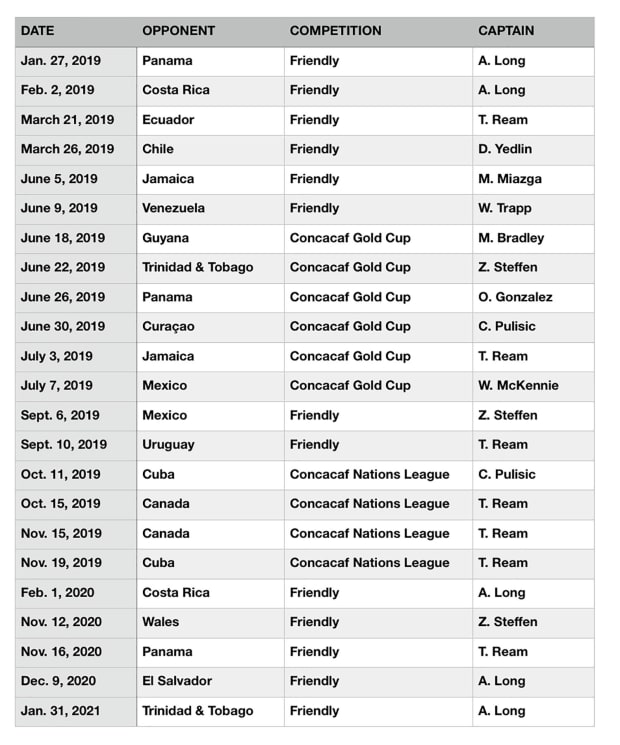

For the first 10 months of his tenure, Berhalter and his staff selected a new Leadership Council for each camp, testing out a range of players, young and old, and giving them a chance to lead and learn. Game captains would be appointed from among Council members. For Berhalter’s first two matches, friendlies against Panama and Costa Rica, New York Red Bulls defender Aaron Long was selected to wear the armband.

“[Berhalter] speaks to me either a day or two before the game and he’s like, ‘Hey, I’m thinking about making you captain for the game against whoever it is at the time,’” Long said. “He says, ‘How are you feeling about that?’ And I’m like, ‘Great, I would love to.’ And he’s like, ‘O.K. Let’s do it. Lead the team.’”

The rest of the group is informed several hours before the game as Berhalter is going through that day’s lineup and player roles and instructions.

Long said that he and Bradley spoke frequently during that first camp, but they never had a conversation specifically about the passing of the baton/armband. Bradley declined to be interviewed for this story. Long told Sports Illustrated that he saw the honor as an affirmation of his camp performance.

“He’s choosing me for a reason. He could’ve chosen 20 other players throughout that camp,” Long said. “I believe it’s from the way I’ve been acting in camp, the way I was carrying myself, the way I was training, the intensity I brought to the group, the way I speak to my teammates. … I’m taking it as, do everything that you’ve been doing and take that into the game. Don’t shy away form the challenge and be yourself, because thats why he’s choosing you.”

Berhalter continued with the temporary leadership councils and captaincy rotation through that summer’s Concacaf Gold Cup. Bradley wore the armband in the opener against Guyana, and Pulisic got his first chance to captain the side in the quarterfinals. Older (Omar Gonzalez) and younger (Zack Steffen) took their turns.

As the final showdown with Mexico approached, Berhalter decided to switch it up. Instead of having a veteran lead the team out under the lights at Soldier Field, he’d see whether one of his rising stars might rise to that occasion. So Weston McKennie captained the team that night in Chicago. It went poorly. McKennie struggled at times during a nail-biting decider, was beaten on the play that resulted in El Tri’s game-winning goal and then bailed on his media responsibilities following the match.

Berhalter doesn’t regret the choice. In fact, he points to it as an example of why the gradual introduction to national team leadership is so vital for this group.

“That’s the beauty of it. That’s my favorite part about it, is that it didn’t go well,” Berhalter said. “Because Weston learned and to me, that’s what this is about. That’s what this whole thing is about, is trying to develop these qualities—working with the players to develop these qualities and letting them fail sometimes, because that’s often when you learn the most, is from failure.”

In October 2019, it was time to put a permanent Council into place. At camp ahead of the USA’s Concacaf Nations League opener, and over email for those who weren’t called in, members of the player pool pondered a list of their peers and selected those who they thought had emerged as team leaders. Six players were elected to the Council: Long, McKennie, Pulisic, Steffen, midfielder Tyler Adams and defender Tim Ream. Berhalter made a list of alternates who fill in when permanent members aren’t available, like at the MLS-heavy January camp.

“He spoke to the Leadership Council as a group, saying, ‘Hey guys, this is going to be our leadership group going forward. When the players want to talk to the coaching staff or to me about anything, they can go through you guys. If you guys ever are hearing anything throughout camp or from the players and you want to speak to me about anything that comes up, you guys have a direct line to me,’” Long recalled.

“It’s nice to have that leadership group that players no matter who’s in camp can look to,” he continued. “On the day, it doesn’t matter who’s wearing the armband because there’s a group of players on the field that feel like that it’s their responsibility, that they can step up and be a leader at any moment. You don’t need the armband to show that. And when it is on, you don’t act any different. You play in every game the exact same way.”

When Berhalter said he was open to feedback on anything and everything, he meant it. Long said that in November 2019, when the USA met in Florida to prepare for its second pair of Nations League games, there was player concern over training times. To strike a balance between the men arriving from Europe and those coming from the western U.S., the coaching staff decided to start training at 2 p.m. The players were uncomfortable.

“Everyone was like, ‘This sucks. We hate training at 2 o’clock. Let’s train in the morning like we do at our clubs. We’re well rested now. The jet lag is out of us. They’re like, ‘Can we switch trainings back to 10?’ So the Leadership Council talked to Gregg,” Long said.

Training time immediately reverted to 10 a.m. The USA hammered Canada, 4-1, in Orlando and then beat Cuba, 4-0, in the Cayman Islands to top its group and advance to this June’s Nations League final four.

Whether it’s a big issue or a small issue doesn’t matter. Again, it’s not all about particulars. Each time the process plays out, it represents another opportunity for these U.S. players to get more comfortable with taking control of their careers, their team and their destiny. It builds confidence, encourages communication and creates the sort of mental muscle memory that should serve the group well when the stakes are highest. Appointing a permanent captain puts the spotlight on one leader. The structure under Berhalter is supposed to forge a team full of them.

That’s not to say that this was a squad of introverts and wallflowers. Long made it clear that the likes of McKennie, Pulisic and Adams “have no problem speaking their mind about certain things,” and that in a way, they “are who they are because of their confidence and the way they carry themselves.” But the Leadership Council isn’t just about giving multiple players the leeway to lead. It’s about conversation and building consensus, which requires patience and cooperation. And it’s about ensuring different views are aired.

“When Gregg asks our opinions on a certain matter, whatever it is, it’s a lot different than asking one player that’s your captain and you get one opinion from him. That could be stifling,” Long said. “It could be exactly the opinion of the group but it’s hard to know. Now when he asks something of the group and I say something and then right next to me [alternate Council member] Walker Zimmerman will speak up, and then Sebastian Lletget will speak up, then we have three or four opinions. And then when you round those all together it’s such a better representation of our group as a whole. In that way I really like it. It’s such a better way to represent our full group.”

But what about times when there’s a spotlight in search of a spokesperson? What about the moments when one leader, anointed and empowered, understands the responsibility might fall on them to step up and represent their team and country? A national team captaincy is a layered honor and responsibility that makes the holder, if there is one, a sort of national representative and figurehead. Their’s is the face the team, the sport and the country present to the planet. In 2017, it was Bradley who spoke out forcefully against Donald Trump’s immigration policies, letting the world know that the U.S. national team stood for inclusion. And last month, it was women’s national team captain Becky Sauerbrunn who issued a statement criticizing a racially-charged speech by Athletes Council member Seth Jahn and calling for higher diversity, equity and inclusion standards at U.S. Soccer.

The U.S. men don’t have that leader yet, and Berhalter thinks that’s O.K. Each of his players has a platform and the right to speak, as McKennie has demonstrated recently, and initiatives born from conversation and consensus—like the Be The Change jackets worn last fall—can be powerful as well.

“I think you get a lot of different viewpoints and the different viewpoints are welcome,” the coach said. “What I’d say is that we’re unified as a team with our message, and it’s great when the guys amplify that message. It doesn’t necessarily have to come from just one person.”

Said Long, “If it comes down to that and a statement needs to be made from the group and no one feels like, ‘Listen, this is my captain’s armband. This is my responsibility. I’m going to step up and make a statement.’ Then I think in some ways, yeah, we would lack that. But on the other hand, if a statement needs to be made and instead of one person standing up and making a statement, you get three or four guys that can stand up and make that same statement and be on the same page, it might be a stronger message.”

That’s what this national team is building toward. At this point, Berhalter said he thinks his plan is to continue to rotate the armband among members of the Leadership Council, and their alternates if necessary, through this year’s Nations League, Gold Cup and World Cup qualifying matches. Qualifying is scheduled to conclude in March 2022. If that campaign is successful, Berhalter said he can envision naming a single captain for the World Cup in Qatar—a captain for the event. Even then, the Leadership Council would remain in place, and the armband would return to circulation afterward. Nothing will be more important than giving multiple players the room to take ownership of their team.

“It’s great when you see them have to work together to come up with a decision, when you see them have discussions with a coach about decisions and really having to process things,” Berhalter said. “Even discussions when we’re talking about Black Lives Matter and how we’re going to work together, that was done with the Leadership Council. It’s been working really well and it’s been really productive.

“I can imagine as a player, you have someone saying, ‘Well, I want to be permanent captain, and I can completely understand that. For us, we’re saying, ‘O.K., we know players are eager. We know that that’s something they could possibly want, and we want to put them in position to develop as leaders.’”