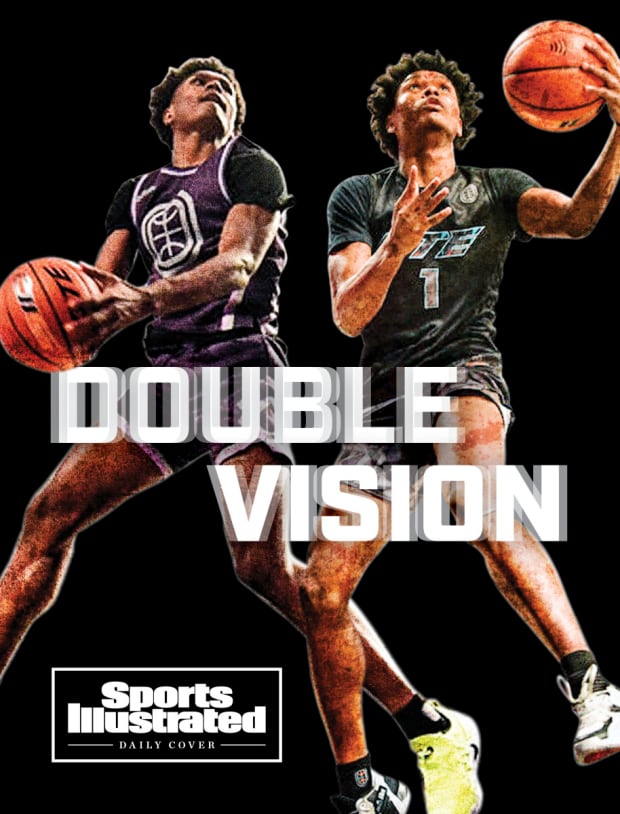

Amen and Ausar Thompson are attempting a new path to the NBA. If they succeed, they could pave the way for other top prospects to follow.

Indulge for a second in a brief history of condiments in basketball. For the older generation, you might start with Hot Sauce, the And1 Mixtape legend whose exploits predated YouTube. Then there was O.J. Mayo, who starred in the prep ranks in the years before social media revolutionized how fans consume highlights. And today, Amen and Ausar Thompson, identical twins and future NBA draft picks, are bickering over yellow mustard—more specifically, its application.

It’s late January in Atlanta, and the 19-year-old brothers are eating lunch in a small, spartan meeting room in Overtime Elite’s 103,000 square-foot, state-of-the-moment basketball facility. The twins wear their hair the same, and apart from some slight facial differences, they’re hard to distinguish off the court. But on this particular day, they’re kind enough to show up in different clothes: Amen with a red Atlanta Hawks T-shirt, Ausar donning a black hoodie.

Having a twin has its benefits: an inescapable support system, a life teammate, so to speak. But for the Thompsons, who in the past two years have gone from little-known prospects to industry trailblazers to lottery-level talents, that has also meant constant competition, including the central conflict of the moment: Whose sandwich was better?

“Mine was good, but I needed to put some mustard on it,” says Amen, who chose roast beef and is sitting next to his brother on a couch at the lunch table.

“Exactly,” says Ausar, who picked the turkey. “So mine was better. Mine had mustard.”

“Yours looked like it had too much mustard,” his brother contends. Amen alleges Ausar’s spreading technique was faulty and, therefore, inferior to his own sandwich, which had no mustard at all. Ausar had squeezed a solitary, unsightly glob on the lettuce, rather than finely spreading a layer onto the wheat bread. His counterpoint: There were, supposedly, no knives in sight.

“Dude wanted me to use my hand,” Ausar says, shaking his head in disgust. To which Amen replies: “You gotta do what you gotta do.”

Jaw-dropping dunks, blocks and passes have endeared the Thompsons to online audiences for much of the past several months, but those clips don’t show you how the proverbial sausage (or sandwich) is made. The 6'7" guards may look like NBA players for those brief seconds, but they are still very much teenagers all the time. They are also the most prominent faces of Overtime Elite’s fledgling operation, which has brought 26 players to Atlanta to live and train full time, while also doubling as limitless content for a massive network dedicated to connecting with youthful audiences.

Courtesy of Overtime Elite (Ausar, left, and Amen)

Overtime began as one of many modest online platforms dedicated to filming, aggregating and magnifying player highlights. As the appetite for high school hoops highlights grew, it became one of the dominant brands in that space. And, with the inception of the Overtime Elite (OTE) program in early 2021, it has since embarked on a self-stated mission to disrupt the sports world in both the physical and digital spheres. It aims to carve a niche in a basketball system that’s historically been change-resistant and allow players to monetize the power of their individual brands while their names are hot. It also presents an alternative to attending college, as a springboard for teenage players to pursue NBA dreams.

The breadth and reach of Overtime is hard to argue, wielding a platform that draws 1.5 billion views per month across social media. But the Thompsons aren’t here to become celebrities (though being here hasn’t hurt). Amen and Ausar each have more than 20,000 followers on Instagram, but neither actively uses Twitter or TikTok—a monastic level of restraint for popular, talented Gen Z athletes.

OTE pays its player-employees a minimum salary of $100K annually, plus bonuses and equity, but the twins aren’t here for the short-term payout, either. They moved from Oakland to Florida to here in Atlanta to play the long game, set firmly on preparing as much as they possibly can for the 2023 NBA draft, for which both are currently tracking as potential lottery picks. Overtime is known for pushing flashy highlights, but there’s substance to what’s happening here: Pro scouts have filed into the building all season, and many have come away raving about the Thompsons.

“If you look from the outside, it may look like all we do is play basketball and, like, dunk and stuff,” Ausar says, while his brother agrees through a mouthful of chips. “Our actual practices are way harder than the practices I've had my whole life. They're longer, a lot more running. It's not as easy as it looks.

“They’re not always gonna film the work everybody puts in, but there’s so many people here at 8 o’ clock every night. Early in the morning, 6 a.m. These things happen way before the cameras start to roll.”

Amen and Ausar are two of the older players in the program—more than two years older than their roommate, Jalen Lewis, another NBA prospect with Bay Area roots. Overtime Elite’s players, whose ages range from 16 to 20, live a short distance from the facility—which stands on the shoulders of successful funding rounds and on a lot that used to be outdoor tennis courts—in Atlanta’s Atlantic Station area, just north of downtown. This allows for essentially limitless time in the gym, where they play, practice, lift and recover. They also go to class: OTE’s academic side has built out a curriculum for the players, most of whom are still finishing high school. The small class sizes give each player plenty of individual attention and a support system; OTE’s teachers regularly sit courtside at games.

Overtime runs a shuttle back and forth from the facility to the players’ apartments, which by the twins’ estimation is just seven minutes away on foot. Still, citing the modest but chilly Atlanta weather, the Thompsons have been taking embarrassingly brief Uber rides home after hours. “I always think they're gonna say something to me after they drive 40 seconds to drop me off,” Amen says. He makes sure to tip well.

Courtesy of Overtime Elite

As with any set of identical twins, distinguishing Amen and Ausar can be a challenge. Overtime purposely placed them on separate teams, which aids scouts in telling them apart, but the distinctions between their games are subtle and require repeat viewings. Twins often grow up playing as teammates, and their skill sets often develop to complement one another. It’s not as clear cut with the Thompsons, who are both stellar transition players and high-flying athletes with advanced feel for the game. They grew up interchanging positions as tall, versatile perimeter players.

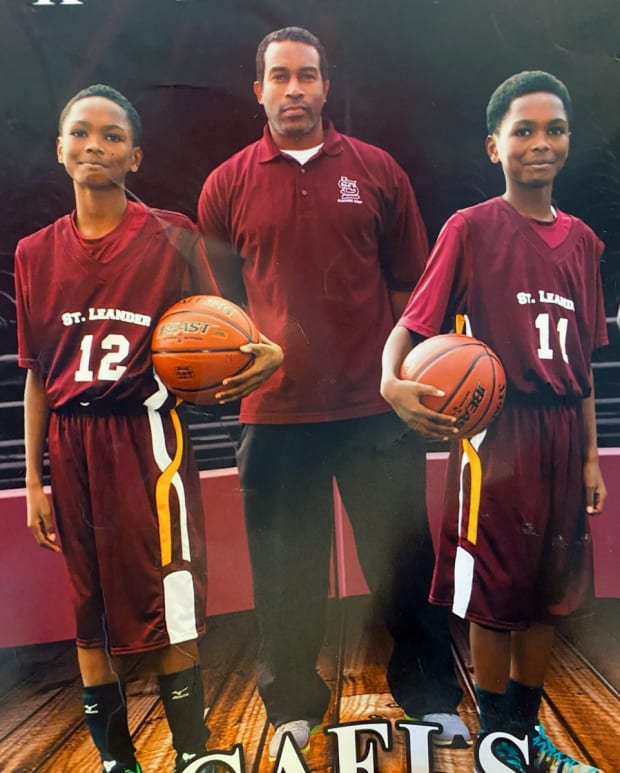

It became apparent to Troy Thompson that his sons were more than just regular levels of good as they rolled the competition in Oakland’s CYO league, operated by the local Catholic diocese. Amen and Ausar were tall for their age, and would frequently train with their older brother, also named Troy, eight years their senior. Their father insisted they play up with older kids not only to test their mettle, but to prevent them from being parked in the post. They made quite a team, blowing by opponents with speed and fast-improving guard skills.

As high school drew closer, their father felt they needed a tougher challenge. Following what he describes as a “family wrestling match” over the future, the twins relocated to Florida in eighth grade, where their father had spent most of his young adulthood. They would get a chance to start high school basketball a year early at an academic-focused private school named Pine Crest in Fort Lauderdale.

“As parents, one of our major jobs is to sacrifice and make the best decisions for our kids and set that framework,” Troy Thompson says. “So when it’s their time to make the decision, they can think it through. And they’ve seen processes and they’ve seen how faith works, just believing in what you're doing and going all out how it can work for you.”

Amen and Ausar grew gradually, with similar skill sets and unselfish styles that made them devastating in tandem. They began creeping onto national recruiting rankings in the summer of 2020. Fresh off leading Pine Crest to Florida’s 4A state title as juniors in the spring of ’21, the Thompsons, consensus top-40 recruits at the time, caught the attention of Overtime’s scouting director, Tim Fuller, at an AAU event. Colleges were just starting to line up in earnest for the twins, who were tracking as All-American–level recruits and would have had their choice of schools the longer they waited. Fuller noticed their relentless approach to the game, attacking in the open court and wreaking havoc defensively. Overtime began its pursuit, working to get a hold of Troy, who was elusive by basketball-dad standards. “In the world of high-level prospects that take lots of recruiting calls, they weren't as open in that way,” says Brandon Williams, OTE’s EVP and head of basketball operations. Even Troy’s voicemail played hard to get. Please do not try to leave a message.

Courtesy of the Thompson Family

Overtime Elite, meanwhile, in its efforts to break into the tightly woven space that funnels young prospects to college and onward, could ill-afford to tip its hand. “We kept secret who we were talking to, because we needed the cloak of darkness to be successful last year,” says Williams, who worked as an assistant general manager for the Sacramento Kings from 2017 to ’19, and in the Philadelphia 76ers’ front office before that.

The recruitment took place digitally—Overtime had no facility to flaunt at that point—but the message landed. The idea of an individually tailored basketball education, one that focused on the right areas of their game, eliminated unnecessary travel and stress, and took the burden off the family, got them in the door with the Thompsons. The twins agreed they had outgrown their current environment. There was appeal in trying something new and personalized. “We always wanted to go to college and play March Madness,” Amen says. “But my main goal was never to be a college star, it's to make it in the NBA and be one of the best. And just be ready [for that]. And I feel like OTE, at the end of the day, was my best chance of being closer to being an NBA player.”

Had they wanted it, there would have been a pathway to graduating early and entering the draft in 2022. But assuming they stayed on schedule, the twins’ time in college would have lasted less than a year, from the time they arrived on campus in the summer to the end of the next college season, after which they’d immediately begin preparing for the ’23 draft. Overtime sold them on the longer view. It framed its offer as a 24-month runway, not just an alternative to college, but also to their senior year of high school, accelerating their development with constant training and gym access, and NBA-quality instruction. There would be maximum time and resources over two years to get their jumpers straight and bodies prepared for the pros.

“There’s a concession,” Williams admits, “that you can’t get the full college experience. But that’s only eight months out of this huge window. For some of our younger guys, that’s 36 months. It’s us today versus [your] high school today in terms of resources and competition. So if you just sit there with, like, a Dr. Evil kind of approach, it starts to make sense.” Effectively, they’d skip the line, while most of their peers remained in high school.

The Thompsons officially joined OTE in May 2021, days after another set of Florida-based twins, Matt and Ryan Bewley, became the first prospects to sign. The following week, OTE signed Dominican guard Jean Montero, a projected NBA draft pick who had previously developed in Spain at Gran Canaria, one of Europe’s top academies. Highly regarded players continued to sign on, including ’22 guards Jazian Gortman and Bryce Griggs, and standouts Tyler Smith and Bryson Warren, who were set to graduate high school in '23. An impressive October pro day signaled to NBA teams that return trips would be necessary, with roughly a dozen players tracking as legitimate prospects, headlined by the Thompsons.

“The Thompsons are the crown jewel of the OTE program right now,” says one Western Conference scout. “In a gym of kids who are all high level in their own right, they stand out almost instantly. Those two are the ones right now who pop as having the highest potential in terms of really being lottery picks and impact NBA guys. They’re quick-twitchy, have great bodies and are developing their all-around skill sets. The sky’s the limit.”

Overtime Elite’s talent distribution can be reasonably likened to a summer All-Star camp, with a handful of truly high-end prospects and no glaring weak links. Not everyone in the program is going to play in the NBA, but the depth of quality lends itself to instructive head-to-head play and positive peer pressure. Overtime’s facility has the technology to not only track shots, but also determine who’s spent the most time in the gym over a given period. Players received comprehensive midseason progress reports to help guide their development. “They get access and also feedback to measure their commitment to the craft versus your peers,” says Aaron Ryan, OTE’s commissioner, who was involved in the launches of the WNBA and the NBA’s now G League and 2K League.

Says Kevin Ollie, the former UConn coach and longtime NBA guard who now oversees Overtime’s coaching staff: “We don't have a student section or all that stuff, but we do have some of the top players playing against each other all the time.”

Ollie signed on in April 2021, returning to coaching after a three-year break that followed a controversial exit at UConn, where he led the Huskies to the 2014 title and recently won an $11 million grievance against the university surrounding his firing. He was sold by Overtime’s leadership group on the program’s desire to break new ground, relocating from Miami to Atlanta to take on the job full time. Ollie is under no pressure to win games, tasked simply with guiding the growth and maturation of his charges.

OTE’s 26 players are divided into three teams, headed by industry veterans Dave Leitao, Ryan Gomes and Tim Fanning, with support staff dedicated to film and analytics. “There’s no college team doing this from a developmental standpoint,” Ollie says. “We can give them the answers to the test. Now you just have to apply them.”

Amen has leaned into his role as an on-ball playmaker, emerging as the best passer in the program while learning to harness his size and speed in the half court. “I'd say I’m more aggressive, and I attack more, and I pass more,” he explains. He averaged 13.4 points and 3.7 assists over 24 games, and totaled 54 steals and 30 blocks on the other end. Ausar plays as more of a traditional wing scorer, with more change-of-pace to his handle, and sets himself apart on defense, where growing up he’d typically take the toughest assignment. “He wants to pick [you] up full court,” Amen adds. Ausar averaged 15.1 points and racked up an absurd 44 steals and 54 blocks in 24 games.

Suffice it to say no teenage player is a finished product, and, at the moment, there’s a critical hole in the scouting report for each twin: Neither is a consistent jump shooter yet. Ausar’s splits are slightly better—27.3% from three on 55 attempts and 67.6% from the foul line to Amen’s 19.5% on 41 shots from deep and 47.1% from the stripe—but both acknowledge they have work to do. Without growth in those areas, there will be upside left untapped in the long haul. By all accounts, they have been diligent. “I could see when they were fearful of shooting it, in our [October] pro day, they were so anxious,” says Ollie. “Now, just to see the change in their thinking process. Because you can block your own shot before you even get the ball. You can embrace fear or run away from it. And I think they’re embracing it.”

A popular external knock on the program has been the lack of quality competition, which isn’t entirely off-base: OTE began searching for games after many potential opponents had set their schedules, and, to be fair, all three teams have pretty much blown out the prep schools they’ve faced. Administrators promise the schedule will improve in the future. In addition to those opponents, the three teams played official head-to-head games all season, culminating in a playoff that begins this week. Amen’s team, Team OTE, earned a bye, and Ausar’s team, Team Elite, will face Team Overtime in a one-game playoff for a berth in the inaugural finals, in a best-of-three series.

Courtesy of Overtime Elite

To the objective observer, it’s evident OTE’s players are making serious strides, due in part to the focused environment they occupy, but also due to the simple ability to compete with one another all the time. Imagine growing up with, say, a twin—the constant access to competition commensurate with your own ability, pushing you to improve in your spare time—and extend those benefits to everyone in the program. “This is not a combative meat market, every man for himself. There’s some camaraderie,” Williams says. “We didn't bring guys here to assassinate each other, right? If you are a gifted musician, you want to jam with other gifted musicians. You play the drums, I play the guitar, and it makes us both better.”

Overtime Elite has set broad benchmarks for its own success in adapting an academy model that’s been implemented in Europe for decades. Primarily, its players need to be prepared for whatever their next step may be academically, basketball-wise and from a life skills perspective. To self-sustain in the long run, the product needs to engage fans and grow an already substantial audience. Overtime is betting on the power of its established connection to a younger audience to yield long-term gains.

“You're inviting people into a concept,” says Ryan, “and you're building credibility at the same time.”

There are designs on expanding rosters and potentially adding teams in the future. In recruiting, there are advantages and disadvantages to being a known quantity, and the advent of NIL legislation has given college programs significant ammunition to compensate players, which may enhance the difficulty of future recruiting battles. The NBA’s G League Ignite program offers another alternative. Top prospects have more options than ever. Fighting the established order is never easy, and it only gets harder to operate quietly.

There’s also been speculation around the industry that the NIL developments might eventually lead to Overtime being able to send players on to college, rather than acting as a separate path. Theoretically, OTE’s players could sign away their likenesses, rather than their work product, and appeal the NCAA for college eligibility if the NBA isn’t the ideal, immediate option befitting a player’s readiness.

Regardless, the long-term success of Overtime Elite’s players—and the program as a pathway to the NBA—will be its ultimate recruiting tool.

“To find [the Thompsons] at the high end of the board for next year's draft is a testament to our commitment and to their commitment, quite frankly,” says Ryan. “We expect to see more of that.”

Two prospects, Montero and Dominick Barlow, are in the conversation as potential 2022 draft picks. But OTE’s best chance at the NBA draft’s green room, and all the legitimacy it brings, will come the following June. Perhaps twice.

More SI Daily Covers:

• Scoot Henderson Is in the G League. And He's the Future.

• The NBA Draft’s Projected Top Pick Is Making It Look Easy

• Inside LaMelo Ball’s Breakout Year in Charlotte