Thirty years after his early death from drinking, imagine all that Pete Axthelm—a man of his time, and yet a sports media progressive—could have been.

In the 1970s and ’80s, in New York City, Wall Street types had the Oyster Bar at Grand Central, where they could toast their gains or drown their losses before staggering onto their commuter trains back to the suburbs. Downtown hipsters hung at the Village Vanguard and the White Horse Tavern; the cocaine-and-disco set at Studio 54 and Limelight. And for the media crowd—sports reporters, in particular—there was Runyon’s, wedged between brownstones on East 50th Street, just off Second Avenue. Runyon’s was, of course, a nod to famed newspaperman and short-story writer Damon Runyon, the quintessential hard-bitten and hard-living New Yorker. The bar’s name served, too, as a kind of code, an implied challenge. As Jay Lovinger, a longtime regular and a titan of magazine editing, once put it: “At that place, you kind of wanted to try and out-Runyon Runyon.” That is, patrons were invited—expected, even—to belly up to the bar and show off their wit and storytelling chops. It was assumed that a Runyon’s regular would nourish, yes, their thirst, but also their appetite for the flavorfully seamy tales of the city.

The newspaper types repaired to Runyon’s after the last of their headlines and deadlines. The sports guys—and they were almost exclusively men—from the local TV stations came directly after the 11 p.m. news, still caked in makeup. This was an era when athletes and coaches still socialized with one another, so it was that Keith Hernandez would pop in following Mets games, Walt Frazier would swing by after the Knicks played and a lovably outgoing college basketball coach from across the Hudson, Seton Hall’s Bill Raftery, would blow in whenever the urge struck. Which was often. “You rarely said, ‘I’ll meet you at Runyon’s,’ ” recalls Bob Costas, another stalwart. “You just went in, and you knew at least five or six of a core of two dozen would be there.”

It wasn’t just the locals. Plenty of sportswriters would come straight from LaGuardia Airport, luggage in hand, for a round or two before checking into their hotel. But you had to know the rules. Mike Lupica recalls a day in the summer of 1984, when he was a young Daily News columnist, that an out-of-towner came in, hoping to watch the start of the Los Angeles Olympics. As a Yankees game played on one TV and a Mets game on the other, the man asked: “Would you mind putting on the opening ceremony?”

From behind the bar, a voice bellowed: “We don’t do parades here—unless they’ve got a line on them.”

In this convivial solar system—this conclave of born raconteurs and immodest drinkers—one man was the unquestioned star, the gravitational center. Not only did everyone know Pete Axthelm’s name. They all wanted to be in his orbit.

One source of this popularity: Without lording over anyone, Ax, as he was inevitably known, seemed to do everything better than everyone else. He wrote with more vigor and flair. He told the best stories—but he also knew how and where to find them. He was more natural on TV than the trained sportscasters, his disheveled appearance notwithstanding. He was wittier than the wits and more philosophical than the deep thinkers. He put larger sums into action than even the most hard-core gamblers.

And—this is really saying something—he could drink more heroically than anyone in the joint. Which is why Pete Axthelm didn’t make it to age 48.

Thirty years later, Ax represents sports media’s foremost entry into the canon of blazing artistic talents self-extinguished far too early. The tragedy of his death, though, goes beyond that. In one sense Axthelm was a throwback. As he took his spot near the oaken bar in Runyon’s—he preferred to drink standing up—clutching his Canadian Club, neat, and touting the next day’s races at Yonkers, it would have been easy to picture him in Runyon’s New York, alongside Nathan Detroit or a charismatic bootlegger or some corrupt beat cop.

But Ax was also a man of the future, glimpsing around civilization’s corners. He was socially and culturally progressive, which bled into his writing. (The Los Angeles Times credited him with “guarding the ramparts of the downtrodden.”) Decades before any athlete took a knee, he saw the potential for players to use their platforms for social activism—and sometimes he openly encouraged them to do so. Before DraftKings and FanDuel and betting apps, he envisioned an increasingly busy intersection between sports and wagering, often wondering why leagues weren’t more hospitable to fans who put money on outcomes. (They would profit so much more!) Before mobile devices afforded instant updates he was obsessed about information, stopping a conversation to duck into a booth and call Sports Phone for a score.

Axthelm was also quick to see that the skills of successful journalists are transferable; they don’t have to pick a platform or a medium. And as long as you’re slinging words for a living, television is preferable to print. They pay you more and work you less!

So, it wasn’t just a profound pity that one of the towering sportswriters of his generation drank himself to an early death. It’s that Pete Axthelm died before he could witness all the changes he had anticipated.

Bob Woodward knew what was coming. In the spring of 1965, the future luminary of political journalism would hear a knock on the door of his dorm room at Yale: Axthelm, his fellow senior and scribe, was asking to play gin rummy. “Which meant that Pete was running low on funds,” recalls Woodward. “He was a hustler. But you never felt hustled. He’d let you win enough so you didn’t feel bad when he took your money. Which he always did.”

Axthelm had arrived at Yale, fresh from a Catholic high school, seemingly ahead of the game. He was well-read. He wrote beautifully. He appeared to know something about everything, and he was always game to learn more. Woodward remembers Axthelm as “brilliant . . . the guy we all figured was going to write the great American novel.”

Having lost his father when he was 15, Ax was already, in many ways, mature beyond his years. He could play cards and shoot pool and mix drinks and move easily among peer groups. Says Gerold Libby, a fellow Yalie and later a prominent L.A. lawyer, “Most of my classmates were anxious about academics. But there were a handful of people capable enough to rise above all of that. [Pete] was unburdened by the demands of an academic curriculum.”

Axthelm wrote for the Yale Daily News, eventually becoming sports editor. He could hold his own in the most challenging course and dominate the most elevated dining hall debate. His senior thesis, titled The Modern Confessional Novel, was so precociously brilliant that Yale University Press published it in book form.

Comfortable as he was with his mostly white and wealthy classmates, he was equally at ease talking sports or music with the cafeteria workers. Influenced by a grandfather who worked at Belmont Park, he was drawn to characters on life’s sooty, sweaty margins. That, and he was drawn to gambling. “He was smart and versatile, interested in high culture,” says Woodward. “And definitely interested in low culture.”

It was also at Yale that Axthelm developed his love of drinking. When he wasn’t at the Daily News building, odds were good that he was at a dive near campus called Rudy’s. Perhaps his closest friend at the time, Charles Dillingham (who later became a theater director in L.A.), recalls the night he and Axthelm stared longingly at the bottles arrayed behind Rudy’s bar. How long would it take to drain the entire inventory? they wondered. “Hm,” Ax said pensively. “How are you for February?”

During his senior year Axthelm appeased his mother by taking the LSAT. Attending law school was a way to avoid the Vietnam draft and a fallback for liberal-arts types skilled with words and logic. Axthelm didn’t study for the test much. He stayed up late drinking and playing poker the night before he took it. He earned a perfect score.

But Ax never bothered applying to law school; he already had a career path. He’d met Jimmy Breslin, the inimitable newspaper columnist, who recommended this mordantly funny and freakishly fast-writing Yalie to his bosses at the New York Herald Tribune. (One telling of the Breslin-Axthelm meeting has the two crossing paths at the racetrack. Of course.) As it happened, the paper’s owner, Jock Whitney, was a Yale graduate who traveled often to New Haven. (He also knew his way around a racetrack; the Whitney Stakes, run every summer at Saratoga, is a family legacy.) After a brief interview in the back of Whitney’s limousine, Ax got the job. He would be a Tribune turf writer while still in school.

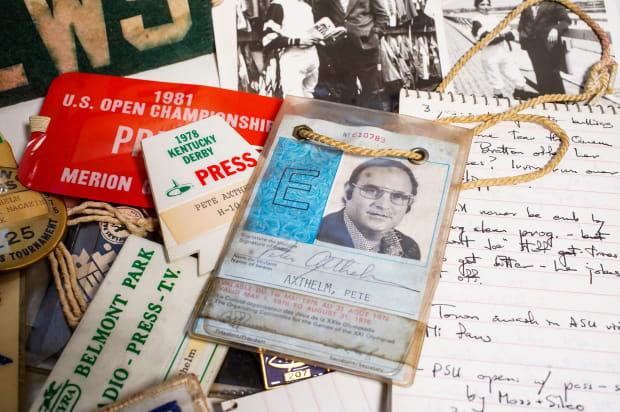

Yale’s class of ’65 graduated on a cloudless afternoon in June. For many, it was a happy rite of passage. Axthelm, though, wasn’t there. He skipped the festivities to cover the races at Belmont.

As one of the great perks of his job, Axthelm got to write for the Trib’s Sunday magazine. The editor, Clay Felker, gave so much latitude to his writers—Breslin; Tom Wolfe; Gail Sheehy; Charles Portis, who was working on his second novel, True Grit—that their freewheeling style got its own catchy name: new journalism.

After a year or so, Axthelm was picked off by Sports Illustrated (where a story about the New York Rangers began: “There is something about a hockey puck zinging in at 80 mph that brings out the expressiveness in goalies”) and then, two years later, by the Washington Post–funded Newsweek, a hipper, more left-leaning alternative to Time. This was the golden age of the newsweekly, and it was an ideal forum for Axthelm, who knew his interview requests would be granted. He could travel—he joked that some of his most creative writing was in his expense report—or stay home and write from his Manhattan apartment.

Early on at Newsweek, Axthelm, then 25, went to Mexico City for the 1968 Summer Olympics, and there he did more than write columns and file dispatches; he played a muted role in the Games’ seminal moment. Axthelm was quick to see the occasion of a global sporting event as a stage for protest, and he covered the events wearing a white button adorned with the letters OPHR, for the Olympic Project for Human Rights, an organization led by sociologist Harry Edwards to protest systemic racism.

In talking with Edwards about how to send a powerful message from the podium, Axthelm also got to know a pair of American sprinters, John Carlos and Tommie Smith, and he watched the 200 meter final in the stands with their wives, not in the press box. When the race ended—Smith took gold, Carlos bronze—Ax sprinted down the gangway to see his friends. Carlos had run wearing an OPHR button, but Smith had not. He asked for one, and Axthelm shared his.

The two sprinters then took the podium. In an image that endures a half-century later, as the national anthem played, they bowed their heads and each raised a gloved, clenched fist in protest against racial injustice. The Los Angeles Times would later note of the famous moment (photos of which capture the white buttons, partially obscuring the U in USA on each runner’s track jacket): “Whereas folks looking at it draw back in shock, [Axthelm] smiled knowingly. It was like cashing a bet on a race in the bag.”

Back at the hotel, Axthelm pecked out his account for Newsweek, writing: “Judged against some of the alternatives that black militants had considered, the silent tableau seemed fairly mild.”

A year later Axthelm began work on his second book, which married his high-low sensibilities. He would cover the Knicks, who featured Bill Bradley—a Princeton grad, also class of ’65—and braid that account with dispatches from blacktop courts like Rucker Park, in Harlem, where “street ballplayers” tried to find their own versions of hoops salvation.

Published in 1970, The City Game became an instant classic. The narrative gods had smiled on Axthelm—the Knicks beat the Lakers in the Finals that May—but the book remains at its soaring best when he profiles Rucker legends like Earl (the Goat) Manigault, whose skills (“freewheeling, unbelievably high-jumping, and innovative”) were offset by “weaknesses and doubts that left him vulnerable.” Writes Axthelm: “Earl is now in his mid-twenties, a dope addict, in prison. . . . He had symbolized all that was sublime and terrible about this city game.”

Axthelm explains the codes and slang and fashion of the blacktop, but he’s not the clinical anthropologist. He renders characters with empathy, leaving readers to consider how bad luck and a few lousy decisions can determine a player’s trajectory. The New York Times hailed the writer as “a poet. . . . [His] eye is cinemascopic, his prose precise.”

All the while Axthelm continued spinning gold at Newsweek, where he distinguished himself for his speed and his versatility in assignments beyond sports. The magazine went to print on Fridays. Time and again, Ax would start writing that morning, drinking his black coffee and puffing on a cigar. A few hours later he’d have a polished story on anything from Vietnam to the Son of Sam killer to Willie Nelson. Over the span of a few weeks in 1973 he wrote cover stories on Loretta Lynn, the New York mafia and Secretariat.

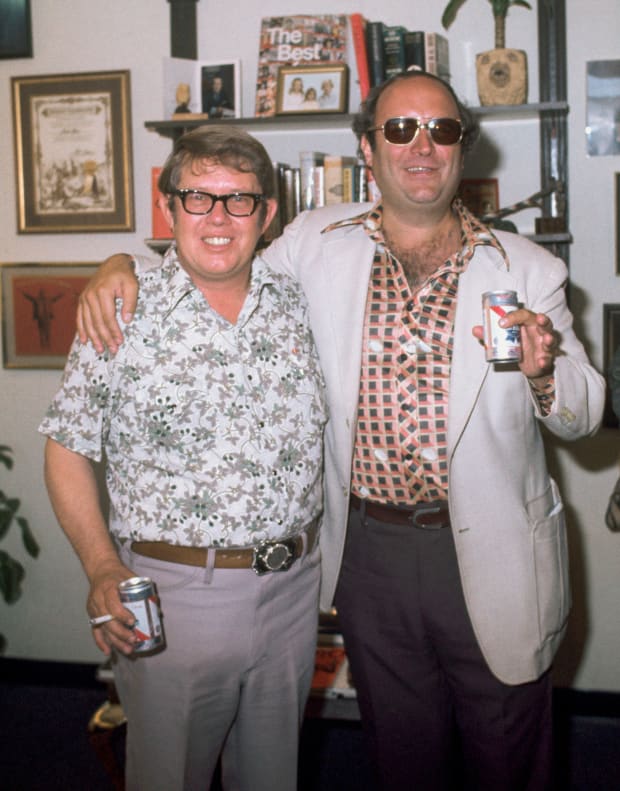

Axthelm and the other Newsweek sportswriter, Pete Bonventre (who met his wife at Runyon’s), became wingmen. The friendship between Pete A. and Pete B., as they were known, superseded any rivalry. They divvied up stories and critiqued each other’s work. Not that Axthelm required polishing. Which he knew. Pete A. would fling his copy at Pete B., smile wryly and say, “Read it and weep!”

Covering the Munich Olympics, in 1972, Axthelm spent the first week in the press center, mostly socializing as he looked, half-heartedly, for an offbeat story. From New York, a Newsweek editor ordered up a piece on the Games’ breakout star, a teenage Russian gymnast. “Who the f--- is Olga Korbut?” Axthelm replied.

“You’re kidding, right? You’re in Munich and you’re learning about Olga Korbut from me?”

Axthelm held his hand over the phone and surveyed his colleagues: “Do any of you know about Olga Korbut?”

Barely a day later he fired off a story that thoroughly disguised his ignorance. “It was like playing jazz on a piano when he wrote,” says Bonventre. “He’d riff and smile—he’d never agonize.” Axthelm could report, work sources and write earnest news as well. A week after the Korbut piece, he and Bonventre cowrote a moving, deeply reported story about the massacre of Israeli athletes and coaches.

Axthelm wrote with flair, but also with authority. As fond as he was for underdogs and strivers, he had no tolerance for those who abused their power or undermined the integrity of sport. Here’s the lead to his May 1982 Newsweek profile of spitballer Gaylord Perry:

He scowls at the world from behind a growth of gray stubble, his small darting eyes always searching for a competitive edge. Slathered in grease and heat rub, he smells like a ransacked pharmacy. He is superstitious and set in his ways, and those who interrupt his grumpy pregame rituals may find him an intolerant bully. Gaylord Perry . . . embodies many of the rough-hewn, independent pioneer instincts. But he leavens them with a thoroughly modern tendency. He cheats.

As often as Axthelm wrote about stars and covered big events, whenever possible he circled fringe figures, especially those with connections to gambling. The railbirds and other hapless bettors held particular appeal. One typical Axthelm gem: an October 1981 profile of a fan at the MLB All-Star Game in Cleveland who wagered $50 that he would catch a foul ball. (Spoiler: He did not.)

In the late 1970s, The Washington Post launched another magazine, Inside Sports, to compete with SI. The founding editor, John Walsh, was a character’s character—a former Rolling Stone boss who kept the company of rock stars and Hollywood types, like Bill Murray—and he hired a murderer’s row of sportswriters: Tony Kornheiser, Gary Smith, Diane K. Shah. He also gave Ax a freelance contract, on top of his Newsweek gig, to come on as a gambling columnist.

Axthelm didn’t merely explore the sports betting subculture; he inhabited it. A not insignificant chunk of his income went toward wagering. Yes, it was the gambler’s rush, the surges in fortune, the oscillating moods. Beyond that, though, he saw something almost metaphysical in gambling. Drawing on the philosophers he’d studied at Yale and the diet of religion he’d consumed in high school, Axthelm concocted a sort of Tao of gambling. There was something pure—vital, even—about taking a stake in an outcome yet determined. He often shared his creed with others: “You gotta make at least one bet every day, or else you don’t know if you’re walking around lucky.”

Axthelm talked more about the losses than the wins. Before the term fully entered the lexicon, he had a personal compendium of “bad beat” stories—dubious disqualifications, near misses, photo finishes. But he had plenty of wins, too. And who knows? The next wager could be a windfall.

Lupica recalls Axthelm’s flashing an expansive smile when Steve Cauthen won the 1978 Triple Crown aboard Affirmed. Apart from Ax’s authentic happiness over the teenage jockey’s success, he had a contract to write Cauthen’s book, eventually titled The Kid, which would now fetch a heftier advance. “My enduring vision of Affirmed versus Alydar is not those three photo finishes,” says Lupica. “It’s the image of Pete running alongside Cauthen and the horse, taking notes, looking like it was Christmas morning.”

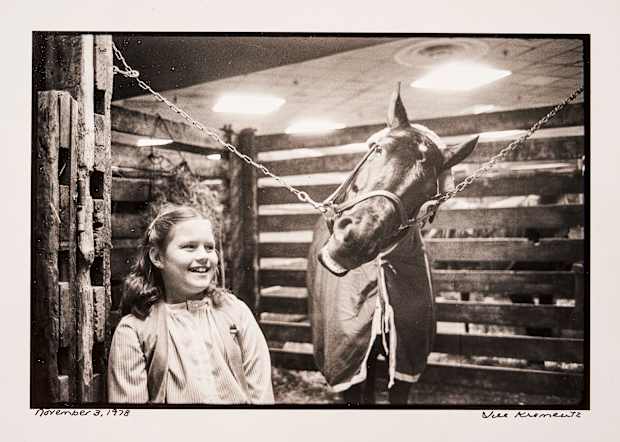

If Axthelm was seduced by horse racing and gambling and drinking, so too did women hold a power over him. His marriage to Jill Delaney, in the mid-1960s, brought him a daughter, Megan. Pete would take her to Runyon’s and order her a sizzler steak; he’d teach her to play gin and to gamble; and when he was away on assignment he would, invariably, mail a postcard. “People ask if he was strict,” says Megan, who recalls father and daughter bonding over the grifter movie Paper Moon. “Yeah. Never play the lottery. Never bet to place or show—only to win. And here’s how you read the other guy’s hand. He wasn’t a drive-you-to-soccer-practice kind of dad, but he was fun. Probably too fun for his own good.”

Devoted as he was to his daughter, Axthelm’s relationship with Jill was more complicated. “He had a girlfriend in every port,” says Megan. “I don’t know how he got away with it, because they were serious relationships.” Pete and Jill split when Megan was young but remained friends and, Megan says, didn’t bother officially divorcing for another 20-odd years. (A pause to note: Damon Runyon’s own marriage broke up when he fell hard for a Mexican woman while covering the Pancho Villa raid of 1916.)

Axthelm once harbored a particularly strong crush on Phyllis George, then a trailblazing cohost of CBS’s NFL pregame show, as well as the wife of Kentucky Governor John Brown. After prevailing on his Inside Sports editors to assign him a George profile, Axthelm described the ordeal at Runyon’s as he brandished the published story.

“Damn,” Ax lamented. “They changed two words.”

“They only changed two words?” replied Lupica, confused. “That’s great!”

“Yeah,” Axthelm said, “but they were the first two words of the entire piece. Breathtakingly beautiful.”

Most of Axthelm’s stories were long elegies or deeply reported profiles and features, but in his bon mots—his zingers and asides—he could match any writer quip for quip. He likened the Jets to “green fungus.” He referred to the Buccaneers-Packers rivalry as “the Bay of Pigs.” (ESPN’s Chris Berman was borrowing from Ax when he popularized the nickname.) Covering Wimbledon, he laughed when one match was called on account of darkness and fans protested by flinging their seat cushions onto the court. “Typical British,” Axthelm observed to a fellow reporter. “Their idea of a riot is to throw something soft and squishy.”

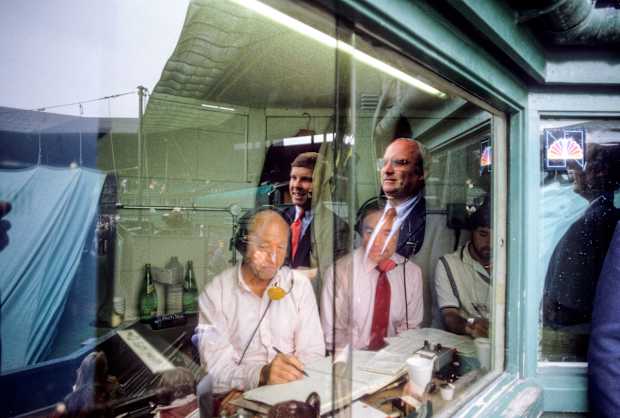

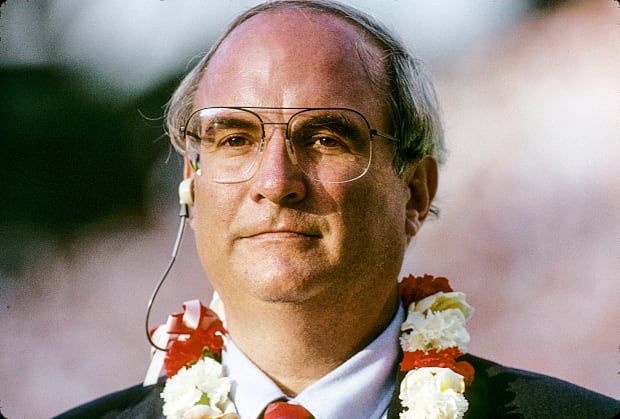

This kind of wit was appealing to TV execs, and in 1980 NBC hired him for his writing artistry, his unfiltered commentary and his horseracing expertise. But mostly Axthelm arrived as an NFL prognosticator and pundit who would pop in periodically. On rival CBS, a gravelly voiced forecaster with an irresistible nickname offered pregame picks each week, giving the appearance of being vaguely connected. Ax would be NBC’s answer to Jimmy the Greek, rumpled and looking like he’d flown in on the red-eye from Vegas.

In 1984, Ax was promoted to a prime slot on NBC’s NFL studio crew, teamed with Costas, a young and versatile host, and Ahmad Rashad, a recently retired star wide receiver. Costas, for one, appreciated Axthelm’s stylish prose and enjoyed the gambling-man persona, as his own father had regularly put up big money on sporting events. But he was concerned that, as a serious writer, Axthelm might be reluctant to indulge in the theatrics of TV—in the schlockier side of the medium. That concern evaporated early on when Axthelm volunteered for a black-and-white halftime send-up of Casablanca, with a production assistant playing a barmaid. “He was game for anything,” says Costas. “Some writers, there’s a line they won’t cross. Ax jumped over it. Happily.”

Still, one would not have described Axthelm as classically telegenic. Even with NBC’s stylists and makeup artists, he looked often as if he had walked into the studio straight out of bed. Or in the rain. His clothes were invariably wrinkled, his comb-over mussed. When the red light was on, he projected a nervous energy and spoke in frantic bursts. As one colleague told producers: “The key is, we have to get him as comfortable in front of the camera as he is in front of the window at Aqueduct.”

Ax was no great prognosticator, perhaps because his picks were based not on algorithms or advanced statistics; they came from his gut. He readily admitted to having two favorite teams, the Dolphins and the Raiders, and he hated betting against either. (The former employed one of Axthelm’s sources as a defensive coach; the latter was owned by one of his childhood idols, a Brooklyn hustler named Al Davis.) Says Costas, “He had all these superstitions. If a bet was going well, he wouldn’t go to the bathroom. If he had pizza on Saturday night and he won his bets on Sunday, you knew he was going to eat pizza again next Saturday. . . . He was this brilliant thinker and writer—but he was also your crazy Uncle Louie from Bayonne.”

For all his clumsiness, there was an everyman charm to Axthelm on television, and he turned that lack of polish into a virtue. Here was the balding, bespectacled, affable guy next to you at the bar. “You could hear the smile in his voice,” says Mary Carillo, who was playing on the pro tennis circuit, in the 1970s, when she first befriended Axthelm, and who later became a Runyon’s regular and then an NBC commentator herself. “He had this playfulness. . . . He didn’t try to act like a suit. He knew his voice and knew that’s what people wanted.”

More than one of Axthelm’s friends would speculate on another reason he took to TV: It was more conducive to the drinking that was starting to figure more prominently in his life. “Writing is hard,” William Nack, the longtime SI writer, once told a friend. “TV, for him, wasn’t.”

Without looming deadlines, Axthelm was free to get loaded as soon as a show ended. Owing largely to his drinking, he aged conspicuously. Viewers were, without fail, shocked to learn he was two decades younger than they’d assumed. Megan noticed the decline, too: “He was never falling-down drunk or face-planting in the birthday cake, but more and more, he would be slurring his words.”

After a few seasons NBC moved on from Axthelm. And in 1988, Jimmy the Greek made some racist comments about Black athletes and breeding, costing him his CBS gig. Combined, this marked an opportunity for the NFL, which had never been comfortable attaching itself to sports wagering. (Those concerns only intensified after revelations about Pete Rose’s baseball betting in ’89 tore MLB asunder.) Millions of Americans might have been filling out pools or handing in wager slips every Sunday, but the league made clear to its TV partners: They were no longer to mention gambling on their broadcasts.

By this point, the drinking that had always been part of Ax’s charm and personality was taking over. He had no interest, though, in dialing back. A string of friends told him that he was killing himself. His response: If you took away my drinking, I wouldn’t be living. So I lose either way.

The drinking was exacting a price on his work, too. After two decades at Newsweek he was suddenly blowing deadlines, his prose slipping. Happy as he was to indulge in TV froth, writing was different, sacred—and so when he moved to People magazine he had to have known that, in terms of gravitas, it was a demotion. (“Can you imagine,” he said to Bonventre, “I’m ending my career at People?”) And yet he struggled there, too. Bonventre, on one occasion, quietly called management, offering to help edit Axthelm. “Don’t do it,” warned one editor at People. “He’ll break your heart.”

Meanwhile, after Inside Sports died a noble death, John Walsh hooked on with a cable startup in the hinterlands of Connecticut. The old editor hired Axthelm at ESPN, which was starting to turn a profit, and paired him with a young, ambitious field producer named Norby Williamson. (“That guy is going to run the company one day,” Axthelm said of Williamson—yet another bit of foresight.) Ax was there mostly for studio work, again playfully picking NFL games, and he was often paired alongside a burly host with a booming voice. (Berman would eventually replicate Axthelm’s likable prognosticator shtick, too, turning it into an alter ego he called the Swami.)

Alas, Axthelm struggled at times to get through his show. He was gaunt and looked tired. His clothes no longer fit his withering body. Friends would ring one another while he was on TV and commiserate about his appearance, speculating about how much he’d been drinking. Bonventre got a call one night from Breslin, disgusted that his protégé was, in effect, disrespecting his own talent. And, also, Breslin wondered: Couldn’t he at least drink something sophisticated—not Canadian Club?

It fell largely upon Walsh to plead with Axthelm to control his drinking, and by multiple accounts he finally gave an ultimatum: If you don’t get help, your job is in jeopardy. “Yeah,” Axthelm replied resignedly, “my daughter says the same thing.”

Then and there Walsh realized the hopelessness. If he’s not going to quit for his own daughter, he sure as hell ain’t quitting for me.

One night around 1990, Axthelm staggered around his Midtown apartment, blood trailing everywhere. The alcohol had stripped away the lining of his esophagus, and every time he inhaled, he spat up plasma. He might have bled to death had a friend not come by. Nack paid a visit to the hospital and implored, “Pete, you gotta stop drinking.”

“I can’t,” Axthelm responded. “I can’t cope.”

“What do you mean, you can’t cope?”

“I tried to stop for three days and I couldn’t cope,” said Axthelm. “I’d rather die than quit.” Reflecting on this exchange, Nack would later observe to writer Alex Belth: “And he got his wish.”

There’s an unmistakable irony to it all. Axthelm’s great literary feat, The City Game, was largely about athletes whose talents were undermined by bad choices and bad habits. Ax was in the power corridor of Manhattan, not on the blacktop of Harlem. His gift was writing crisply, not dunking or shooting the J. His poison was alcohol, not heroin. But here was the author, tracing the same arc. Who was he if not Earl the Goat, self-sabotaging and squandering his gifts?

When Yale’s class of 1965 met for its 25th reunion, Axthelm was absent, just as he’d been for graduation. This time, though, he wasn’t at his beloved racetrack. He was in a Pittsburgh hospital, awaiting a liver transplant. It never came. He died on Feb. 2, 1991, at age 47, his luck having officially run out.

The tributes followed, first acknowledging Axthelm as a generational writing talent. Says Walsh, “The cadence he had, the organization, sentence for sentence, the appreciation for language. . . . I edited Jimmy Breslin. I edited Hunter S. Thompson. Kornheiser. [Axthelm] was in that elite category.”

Then the stories, predictably, flowed freely. Most referenced his carousing, his adventures at the track, his alloy of highbrow-lowbrow sensibilities. To the end, he was more proud of the exacta box he scored at Hialeah than he was the perfect LSAT he scored while at Yale.

Thompson, a friend and kindred spirit, eulogized Axthelm in Esquire: “If he couldn’t go to the track he swore he would go to the tomb. He wrote brilliant essays and sometimes asked morbid questions, which eventually led him into a place that some of his friends called ‘the gray area.’ It was an essentially Buddhist concept based in karma, laughter, and occasional human sacrifice.”

When the Runyon’s crew—and so many other giants of sports journalism—toasted Axthelm, they were also saying farewell to something deeper and broader. Newspapers were already headed toward their inexorable, sad decline. Magazines would soon follow. The divide between athletes and the folks who covered them was deepening, draining both intimacy and fun from sportswriting, turning it into something perilously close to a job. Bars were beginning to ban smoking. Depending on your perspective, New York was either losing its grime or losing its color. Much of the Runyon’s roster was abandoning Manhattan, with its unfriendly rents, for places like Florida.

Poorly as he once aged corporeally, three decades later Axthelm has aged damn gracefully as a media archetype. He helped loose an army of writers who either moonlighted in television or decamped there entirely. Who knows whether a print refugee like, say, Kornheiser—an Axthelm protégé—would have gotten even a sniff from a network exec had not another high-strung, witty, occasionally cranky columnist on the Washington Post payroll proved it could be done.

Axthelm’s urban anthropology in The City Game helped unleash an entire industry. The conceit of spending a season with a team spawned a whole genre of books. What’s more, in a profession too often fixated on winners, he showed that losers yielded equally compelling stories, characters and lessons. Before long, writers like David Halberstam, Rick Telander, Darcy Frey and Buzz Bissinger would take up the search, and they in turn would inspire everything from Slam magazine and the And1 Mixtape Tour to documentaries like Last Chance U.

As sports betting and the appeal of action has moved in from the margins, Axthelm’s obsession with odds and lines and probabilities ... it no longer scans so degenerate. If Brent Musburger, at 81, has his own sports gambling network, Lord knows what Axthelm’s profile might be today, at 77. (It’s more than a little fitting that Megan’s son, Matthew Brown, Pete’s grandson, scored an internship several years ago at Barstool Sports by winning a football picks contest.)

As a journalist, Axthelm practiced the antithesis of sticking to sports. Every sportswriter who in 2020 wrote about the Black Lives Matter movement or the COVID-19 crisis—considering sports as society’s connective tissue, not a disembodied organ—was, in effect, channeling Axthelm. And then there’s his writing itself. Damon Runyon may have been the guy they were all trying to emulate, but his stories, while they pack undeniable charm, came larded with clichés and silly plot devices, trapped in a black-and-white era. By contrast, reread Axthelm’s work and, man, it holds up. He wrote with graceful extravagance, but also with grit. There’s anger, but also empathy. His stories are the kind a writer gets only by reporting and observing and asking questions.

Pick a line, any line. He wrote about fans with arms outstretched “not to grasp but to supplicate.” The second baseman Davey Lopes was “the angriest Dodger, fielding the postgame questions as he does ground balls—aggressively and inelegantly.” He described the Celtics as “celebrating springtime by making inches of height advantage into yards—and translating canny court sense into a textbook on how the game should be played.”

His work remains deeply consequential. Metaphors sing. Quotes zing. And in a hard-boiled, soft-hearted, booze-stained, no-bulls--- way, his prose is often, to borrow a phrase, breathtakingly beautiful.