The Indy bubble worked, but it was one of the most incredible undertakings in the history of the NCAA.

INDIANAPOLIS — Chris Pezman never thought his trip to the men's NCAA tournament would begin this way, hustling down a flight of stairs at Assembly Hall, heading toward the court—or as close as he could get to it—while clutching a bag of pharmaceuticals meant for an injured member of Houston.

What happened next was altogether unusual. The Houston athletic director, leaning against a railing overlooking the court, wound back his arm and heaved medication down below toward a team staff member.

“I threw the prescription into the air,” Pezman says, days later. “The thought of throwing anti-inflammatories across a basketball court wasn’t something I had envisioned.”

And yet, here he was, administrator-turned-delivery boy—and medicine-wielding quarterback. Because his own team physicians couldn’t leave the NCAA’s bubble, he was sent off on a mission to retrieve medication from a local pharmacy for ailing guard DeJon Jarreau in the middle of the Cougars’ first-round game against Cleveland State.

Such was the case at the 2021 men's NCAA tournament, where the invisible bubble enveloping the teams here resulted in some of the most bizarre and hysterical stories out of any Big Dance. While the event featured some of the best stories on the court—a record number of upsets (14) and Saturday’s buzzer-beating Final Four finale—the tales from the bubble were just as entertaining.

According to NCAA officials, the four bubbled hotels were only twice penetrated from the outside (no harm was done either time), and only one team (VCU) had to bow out of the dance because of COVID-19 issues. Of the 34 players and staff each team was allowed into the bubble and another few dozen NCAA personnel (about 2,400 total), not one escaped or sneaked out, officials say. At least, not that they know of.

In short, the bubble worked, even if it was one of the most incredible undertakings in the history of the association.

“I got 10 hours of sleep the first four nights in the bubble,” says Mike Fox, a longtime event executive and an independent contractor hired by the NCAA to manage one of the four bubbled hotels. “It shows you the intensity and complexity of this event. I’ve been involved with mega events as far back as I can remember and I have never seen anything so close to this complex.”

Last week, the NCAA approved several of its bubbled workers to speak with Sports Illustrated. Coaches also spoke about the bubble experience, as did players and other team staff members secured in isolation.

They shared their stories—their tales from the bubble.

“It’s been really a great experience. The positives out weight the restrictions,” says Baylor athletic director Mack Rhoades, one of the few ADs who joined their team in the bubble.

Gonzaga’s AD, Mike Roth, is in the bubble as well. The two teams meet in Monday’s national title game.

“Maybe we’re the good luck charms,” Rhoades laughs.

In a way, Monday’s championship affair is a bubble-bursting game where even the loser gets a prize—a release from the bubble. The Zags (31–0) and Bears (27–2) are all that remain of the 68 bubbled teams. They’ve been here for three full weeks, locked away in a single floor of a hotel, rarely allowed to go outside and never granted permission to leave, aside for games and practices.

Over the course of the tournament, when exiting the bubble, there is an exhale of sorts—a bittersweet moment. You were just eliminated, but you are also free now.

Tim Allen, another one of the NCAA’s bubble managers, says he’s witnessed the exhale up close.

“Aaaah, fresh air!” he overheard a player yell earlier in the event when stepping out of one of the four hotels the NCAA used to isolate teams.

After 13 days as a coordinator within the bubble, Susie Towsend exited her lockdown last week, and the first thing she did was fly to visit her son in California and watch a Pacers game.

“I was released from the bubble…” she begins explaining before a pause.

“Wait,” she cackles. “It sounds like I’m talking about prison!”

This, of course, was no prison.

There were plenty of games and plenty of food. The NCAA is in the process of compiling exactly how much food was consumed. During the early days, when 68 teams were sequestered throughout the four hotels in downtown Indianapolis, the numbers were startling. At one hotel, the JW Marriott, 7,000 pounds of chicken were served during the first two days, says Phil Ray, the general manager. One night, Buffalo Wild Wings delivered 19,000 wings to one hotel, says Townsend.

Pizzas came in by the bundle. Each player got a large pie every night if they wanted one.

“You can imagine 34 pizzas coming in and getting them on the bell carts,” Townsend says.

And there were games, plenty of games. Victory Field, a minor league ballpark downtown where teams were allowed for short stretches, was turned into a theater of wiffle ball. It was also Gonzaga coach Mark Few’s favorite spot. Always the outdoorsman, Few would sneak off to the field for calisthenics, which he did barefooted on the outfield grass.

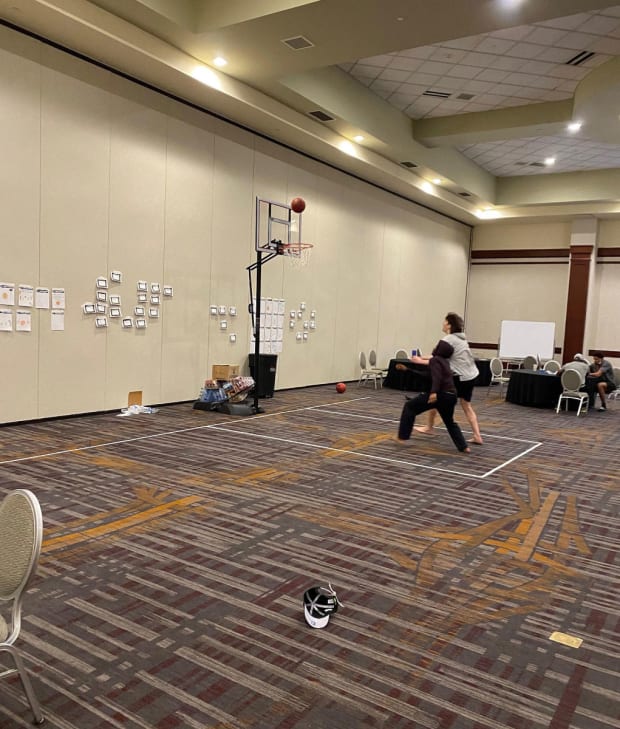

When not outside, Few and the Zags played some mean games of pickleball on a makeshift court inside the hotel. Meanwhile, Baylor created a makeshift court of its own—a basketball one. White tape stuck to a carpeted ballroom floor served as boundaries and a full-size basketball goal leaned against a hotel wall.

Some teams brought bowling pins and bowling balls with them, setting up their own alley in an expansive portion of the hotel. Cornhole was all the rage. So were card games like Uno.

“A lot of championships have been won in the bubble,” says Rhoades. In Baylor’s case, its deputy athletic director, Dawn Rogers, claimed the Uno title, and Davion Mitchell, one of the team’s stars, won a Connect Four tournament. Guard MaCio Teague was the cornhole champ.

“This will be one that our kids will really remember,” Rhoades says. “You’re isolated, yes, but you’re not isolated from people.”

The biggest gripe in the bubble? Hair.

There were no barbers in it, something the NCAA at first planned to have before the episode with the Kansas City Chiefs, when the team’s barber tested positive for COVID-19 just before the Super Bowl.

It scared officials enough to change plans. There would be no barber.

“Man, I need a barber,” Baylor forward Mark Vital says in an interview over the weekend. “Like, if you can help me do that, before the game, man, please put that out there. We need a barber, man. I'm out here struggling. I got all this stuff from CVS, done combed my hair a thousand times. I need a haircut.”

No barber meant players or team managers cutting one another’s hair. It wasn’t good.

“Players were checking out the sides of their heads,” says one team staff member who wished to remain anonymous. “And they were laughing at one guy—his hairline job was a little uneven.”

Officials didn’t plan on another issue that cropped up amid the bubble: the Jewish holiday of Passover, which began March 27 and ran through Sunday.

“Several coaches came up to us, ‘What are we going to do? If we make Sweet 16, we need to make some arrangements,’” Fox recalls.

Luckily enough, a cook familiar with Passover food (it’s all Kosher) prepared the proper meals. Disaster avoided.

And what would this story be without a dash of superstition? The teams that advanced to the Final Four were offered more expansive meeting space after so many rooms were freed by departing teams. Three teams accepted the change. The other did not, wishing to remain in its small space as it had during a magical run to the Final Four.

“That school will remain nameless, but it was a team that wasn’t supposed to make it to the Final Four,” Allen snickers, clearly referring to No. 11 seed UCLA. “They declined. If that’s superstitious or not, I don’t know.”

The bubble featured some heartwarming moments. None was more powerful, Fox says, than the one between Missouri coach Cuonzo Martin and his son, Chase, who plays for Purdue. On the first day teams arrived, Missouri and Purdue’s meetings rooms just happened to butt up to one another. Dad and son, having not seen one another for a while, embraced in a long, emotional hug. The reunion of the Martins made its way like gossip throughout the Hyatt.

Did you see it!?

Have you heard about it!?

The bubble wasn’t without normal hotel maintenance issues. Housekeeping wasn't allowed on the floors, of course. Trash and laundry were often placed outside of rooms for pickup. NCAA officials created an essential closet on each floor filled with items that would normally be delivered by the front desk or cleaning services.

That included a plunger, an item that got more of a workout than any other, laughs Allen.

“I’d walk down the hall and see the plunger outside of a room,” he says.

Each team had a floor with 34 rooms for each person. Each individual was given two keys for his or her room. In case a player locked himself out or for any other emergency, the director of operations had a key for each room on the floor.

Maybe that wasn’t such a good idea.

“The first four times that we had someone get locked out of the room,” Allen says, “it was, each time, a director of ops who had all the other keys locked in his room.”

Ah yes, life in the bubble! Where athletic directors turned into delivery men.

Pezman’s situation is burned in his mind forever. During Houston’s game against Cleveland State, the team’s star, Jarreau, went down with an injury. Team doctors called in a prescription at a local CVS and then, at halftime of the game, rang Pezman with instructions.

“We’ve got a problem,” the voice told Pezman on the other side of the phone. “We need you to go to the pharmacy. And it closes at 9.”

It was 8:30.

He bolted out of the arena, sped to the pharmacy, picked up the medication, talked his way back into the arena and then, of course, hurled anti-inflammatories across the court.

“It is,” Pezman says, “quite a story.”