Mike Tyson is back in the ring. But the heavyweight he flattened 17 years ago is locked away for life, trying to draw up a next new plan.

The messages arrive at all hours, with the same email subject line: JPay Services—New Incoming Mail. For stretches, they land with weekly regularity; other times, months pass without any correspondence. They’ve all been sent from the same place, a small room deep inside a prison in the swamps of Louisiana. And they’ve all been typed out by the same inmate, locked up for a cocaine-fueled crime spree.

These letters, they're a fast-moving, mostly lucid commentary on the past few years in the U.S., sports and beyond. From the rise of Bills quarterback Josh Allen (the sender writes: “he could put together a HALL OF FAME career”) to the in-ring success of Ukrainian boxer Vasiliy Lomachenko (“f--- however hard he might punch”) to the upcoming Mike Tyson–Roy Jones Jr. boxing exhibition (“both are too damned old to be punching on one another”) to the marches this summer against racial injustice (“sounds like the nation is turning into hell”).

These letters, they also tell an incredible, sometimes verifiable story. About a teenager who went to prison and learned to box and came out ready to challenge the best heavyweights. About a fighter who got his brain battered and bludgeoned. A child who grew up in poverty, and an adult who made millions, only to lose everything. A human being who made the kinds of choices he can never take back; choices he now must find a way to live with. In his emails he grapples with all of this, his tone swinging between extremes. From hopeful to hopeless. Repentant to remorseless. Sorry and not-that-sorry.

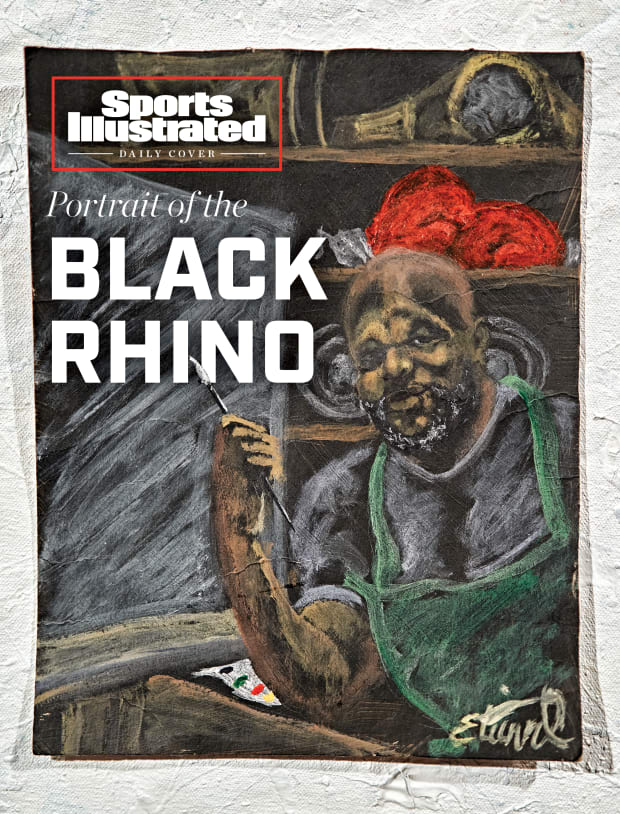

There’s an unexpected tenderness to it all, especially when the writer gets to the hobby he picked up in prison. The desk in his cell. The crate of paint beside his right foot. The brushes resting in an old Pringles can. The blank canvases that slowly fill, Miles Davis and John Coltrane playing softly on a stereo. “When I'm painting,” he writes, “I'm not even in prison. I'm in a world of my own.” With some interest from gallerists, his work now hangs in homes and in offices across the country, one piece even displayed in the headquarters of the New Orleans Police Department. His images, often grounded in Black history, have a serenity to them. They can appear to an outsider as both a way to remember and a way to forget.

In a previous life this man won 29 professional boxing matches. He fought on Showtime against Mike Tyson and drew comparisons to George Foreman and Joe Frazier. He also once pulled a gun on a store clerk and screamed, “Bitch, give me the money!” before turning his weapon on police.

On some level this man understands his fate. On another, he can’t accept his reality. His letters can feel like a tug of war between the two. For more than three years he writes, his memory reliable in some instances and spotty in others; his prose pocked with misspellings; his sentences often incomplete or incoherent, more often than not ignoring the prompts and questions from the other end. He signs his missives Cliff and Clifford and sometimes Black Rhino. He’s prisoner No. 00130104 at Elayn Hunt Correctional Center, right across the Bayou Chene from where he grew up.

Clifford Etienne has been described in one place or another as a monster and a disgrace. He’s also a mentor and a son and a father and a friend; an artist and a barber and a former champion. His story connects all of these disparate worlds, merging crime and punishment and prison reform with sports and fame and second chances, with boxing and brain injuries and mental health. He no longer resembles a professional athlete, he writes, his body more like a “couch pillow,” his head shaved bald, his beard grown out and flecked with “hundreds” of gray hairs. He’s down maybe 30 pounds from his fighting weight and maintains that he’s still “healthy as a thoroughbred.”

At 50, his life is defined by a question: What do you do when it’s over, when there’s nothing left except the sentence to be served and the sentences to be written—the regret and blame swirling in your head? For Clifford Etienne, you try to explain everything and nothing all at once.

***

Etienne writes often about his childhood in rural Louisiana—the money sparse, the existence poor, a large family packed into a small house in New Iberia (home of Tabasco hot sauce, he points out), everyone sharing scraps of food in the leanest times. In most ways, this marked his lone, brief period of innocence. He cites two grandmothers as influences, women who taught him to cook, sew and clean. He dominated in wrestling and baseball (pitcher and second base) and track and field (shot put and discus), but football was to be his ticket out. As a linebacker prospect he stirred up interest from the likes of LSU, Nebraska, Texas A&M and Oklahoma.

He writes in long rambling thoughts and in snippets that race through his history. Like: “Football was my love, which I know would've brought me places. Yet, my first stint of incarceration killed that.”

My first stint. He revisits often his 1988 sentencing, when he was 18, after he joined four friends in robbing customers at a shopping mall in Lafayette. By all accounts, including his own, he knew exactly what he was doing: Trying to obtain what he could not otherwise afford. Seeking a better life.

Sentenced to 40 years—first at Louisiana State Penitentiary, nicknamed Angola after the plantation that once covered the same land; then at Winn and Dixon correctional centers, all in the steamy bridge of the state’s boot—Etienne would soon find out that in this particular part of the country, in this particular prison system, sports could still provide him a sort of escape, if not quite an exit route. Especially at a strapping 6-foot-2, 290 pounds. Out of options, a young man at war with himself discovered boxing. Years later, looking back, Etienne writes: “All of my past trainers … are dead now, except one. I'm sure Whop could give you some good input on how I left a legacy there.”

Whop—like a hard hit, Whop!—is actually Valrice Cooper, who as an inmate himself found new life as a steward of Louisiana’s prison boxing scene, and who kept at it after his release. He knows as much as anyone about the penal leagues—the kind that have long nurtured future fighters like Sonny Liston. He knows how much bigger they were in the Deep South, and how much longer they lasted there than anywhere else. He recounts how each prison would field a team of fighters covering nine different divisions, competing from February to November in front of civilians packed into makeshift stands, and how those fights would play on prison TV as if they were jailhouse Pay-Per-View.

Aspiring fighters, Whop says, would jostle for jobs in boxing training programs, where sparring qualified as work. Whop didn’t meet Etienne until after the boxer had already become the most dominant prison fighter in Louisiana, and they were never all that close. But the trainer did see firsthand how Etienne perfected the science and the art of throwing fists and dodging them. There was a rhythm to his style, how he moved and countered and stepped back and circled toward an opponent. It was dancing and punching, cerebral and brute force—contradictions that the fighter embraced.

Etienne competed as a young man, similar in size to a fully-grown boxer but with the nimble feet of a smaller one. He didn’t wait to land one big punch; he threw dizzying combinations. He ducked and dodged. In some ways, he reminded Whop of a prison version of Muhammad Ali. He moved that well. Hit that hard. “Unbeatable,” Whop says today.

Etienne, on himself: “I was systematic, but always cut off the ring to put my opponent in a blender. That was my inside linebacker mentality.”

After winning 30 bouts inside—his recollection—and never losing at heavyweight or super heavyweight, Etienne earned parole in his tenth year served. He believed he’d found his purpose, and he planned to stalk into the professional ranks and start knocking out free men. Promoters salivated at the chance to watch him try. He had a hell of a story to tell, plus an enthralling nickname. In the prison library he’d read about an endangered species of African rhinoceros, and to a doubting friend he handed over a book as proof.

“That’s you!” the friend bellowed.

***

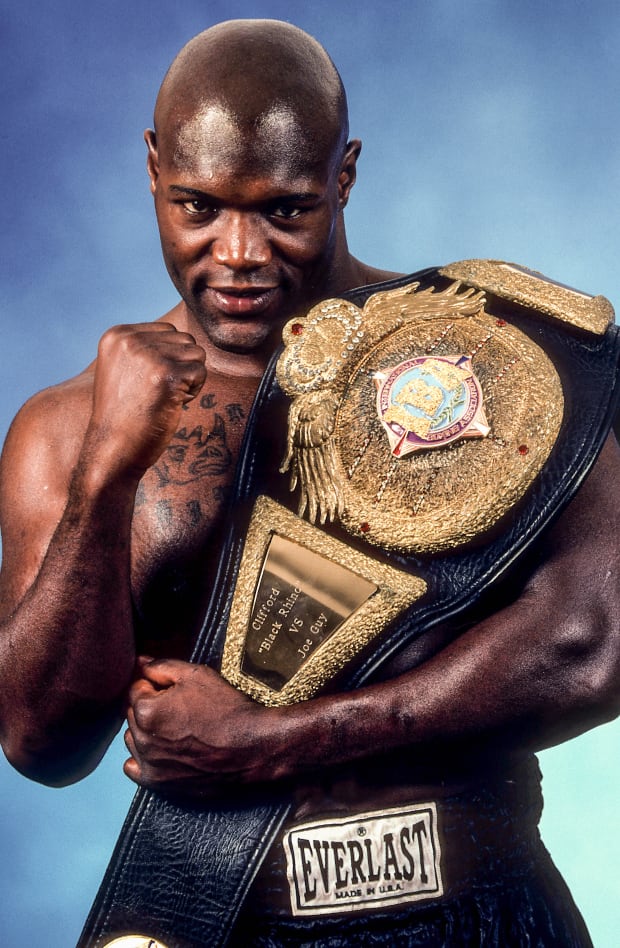

The Black Rhino turned pro in 1998 and knocked out four of his first five opponents, ending three of those fights inside the first round. He rarely took a step backward, eating punches and rebutting them with flurries of his own. He drew blood and savored the rivers of red dripping down his own face. His fights were the types of splattered spectacles that led The Ring magazine to later name him the most exciting heavyweight fighter of the 2000s.

Etienne battered less experienced opponents, and then more seasoned ones, most notably the undefeated Lamon Brewster, a future world champion, in May of 2000. His rise continued, his purses ballooned, and suddenly there were people—new “cousins”—holding their hands out, looking for a piece. He started dabbling in recreational drugs—mostly cocaine, he says; a bump here, a line there. He knocked out two more opponents and scooped up the vacant IBA Continental Heavyweight title in Baton Rouge, halfway between home and Angola. No, it wasn’t a world title, but the belt nonetheless fit snug around his waist.

All the while, Whop marveled at how a boxer from the same prison gym, who ate the same mess hall gruel, came to be on TV, knocking real pros flat on their asses. He started to hold up Etienne as an example for other fighters, to show them how boxing could change their lives. See: Etienne could live a worthwhile existence, even after the crimes he’d committed. You make mistakes, Whop preached, but you still have choices. For a while, the friend he called Big E was making the right ones.

***

Etienne would square off against some of the most punishing heavies of his or any era, absorbing as much abuse as he delivered. He craved the combat, the exchanges, what it meant to measure his will against another man’s fortitude. He didn’t mind, he says, when foes slammed fists into his face and wobbled him and knocked loose hours of memory. There are stretches of days he can no longer remember, chunks of fights he cannot recall at all.

One of those marked his first loss, to Fres Oquendo in Las Vegas, back in March of 2001. That televised bout featured the kind of wince-inducing back-and-forth that fight fans cannot turn away from. Oquendo floored Etienne seven times, landing overhand right after thudding overhand right. But Big E continued to rise and beckon his opponent, right up until the referee stopped the bloodbath in Round 8.

Etienne remembers that fight only partially. He recalls the punishment taken, the sanctioned and celebrated beating Oquendo put on his brain. There’s no way to establish cause and effect; it’s not possible to draw a straight line from that night to his mental state today. Still, his logic tracks when he says: Getting hit in the head that many times in that short amount of time by that powerful of a man would affect anyone long-term. And that was just one night’s work. Beyond that singular beating, Etienne engaged in dozens of clashes—30 bouts in prison, 35 as a pro. He safely estimates that opponents hit him in the head thousands of times.

Years later, Etienne weighed all of this, and the puzzle he put together in his head made enough sense to him that he landed on a diagnosis—even if it’s one that cannot be confirmed until after his death. “Humans love watching brutality, and I loved to box brutally,” he wrote. “I am sure that is why I suffer from CTE. Football players complain of concussions, and they wear ass, shoulder, knee, hip and thigh pads! Plus a helmet. Boxers have none of those. [Football players] have to come off the field for concussion protocols. Almost every time we get hit we receive concussions.”

As the years of correspondence continued, Etienne wrote more and more about CTE, the degenerative brain disease caused by repeated blows to the head. He started looking into what’s widely referred to as “the CTE concussion defense,” an unproven (and overwhelmingly unsuccessful) legal strategy that has been explored in recent years by lawyers looking to explain away the misdeeds of their clients—often former contact or combat sports athletes—by connecting their actions to the brain injuries they suffered at work.

Having exhausted more traditional avenues of appeal, Etienne latched onto this notion; He would seek a reassessment of his sentence, given the damage inflicted on his brain inside of boxing rings. It became apparent, as time wore on, that he saw this as his last, best hope.

***

Etienne won six more bouts after the loss to Oquendo, all thumpers, including another signature victory, against Frans Botha, a decimating South African known as the White Buffalo. (Later in his career, Botha tested positive for performance-enhancing drugs.) Along the way, in real time, Etienne never considered any health risks. Why would he? He felt normal, on top of the damn world. He could think clearly; his brain was not yet scrambled. But he believes, now and forever, that much of the damage had already been done. “I got hit on the back of my head quite a few times and never recovered. Sure, I still got on with my boxing career. But it was the beginning of the end.”

By 2003, promoters had designated Etienne as ready. For the big time, the big one. For Tyson, should the concussive former champ manage to keep his act together long enough to climb back into the ring. Iron Mike, by then spiralling infamously, almost didn’t make it. He threatened that he wouldn’t show up, said he didn’t need the cash, and arrived for the fight in Memphis with a tribal tattoo freshly inked across his face. He obliterated Etienne in a menacing 48 seconds and then, in the post-fight interview, told Jim Gray, bizarrely, that he had fought with a broken back.

Etienne, ultimately, was a footnote to the biggest evening of his life (the fight has little place in his writings), but the spectacle of it all made for a surreal backdrop when he visited his father’s financial advisor, Patrick Burke, shortly after the defeat. Etienne had earned $1 million off those 48 seconds and all the training that went into them, “but he did, shall we say, some stupid things with money before we met,” says Burke.

The boxer had blown a small fortune on Behind the Music stuff: sports cars and jewelry, multiple houses and doomed businesses. He started a bussing company that crashed fast and dreamed up a restaurant that never opened. He told Burke he had failed to file his taxes, and penalties had piled up. That doesn’t even account for the family he helped with house payments and cash for groceries.

Burke recalls seeing Etienne in Nevada a few years later and feeling like the boxer wasn’t quite right. He was, Burke recalls, “Mentally present, but he couldn’t grasp things normally.” He looked closely into Etienne’s eyes. Is he on drugs?

***

It is easy, sometimes, to get lost in Etienne’s movie-script backstory, the fall and inspiring rise before the stunning second fall. One can forget the moment when a life that was pointed away from prison made a U-turn. When a promising fighting career permanently derailed.

Etienne waffles, often uncomfortably, when looking back. He owns his actions in one letter, then in another cuts himself breaks for things that, only by some twist of fate, didn’t happen on the day that landed him back in prison. He focuses on how much worse it all could have been. “I didn't hurt, shoot nor kill anybody,” he writes. “But I was actually sentenced to die in prison!!!”

Whatever his perspective, these are the facts that led a jury to sentence Etienne to a second stint, this time for 160 years—the maximum allowed, when he could have been given as few as 15 years, his lawyer points out—on an array of charges. Including: two counts of attempted murder with a firearm, two counts of attempted second-degree murder, plus attempted carjacking and second-degree kidnapping. On August 10, 2005, the 33-year-old boxer, admittedly high out of his mind on coke, held up a check-cashing business in Baton Rouge, stealing some $2,000 and discharging a firearm into the air because he deemed the clerk to have moved too slowly. Etienne afterward attempted to steal two different cars in his escape, each one with children in the backseat. After crashing the second vehicle he pulled his weapon on two responding officers, only this time the trigger jammed. Etienne argued, and still argues: Yes, it was awful, but it could have been worse. His sentence suggests that sentiment moved no one.

Etienne’s crimes seemed straightforward, the result of bad decisions for which he was tried and sentenced. But there were signs, even back then, that something was off, perhaps beyond his drug use. His wife, Tiffany, testified at trial that his behavior had become increasingly erratic and scary in the previous months, to the point that she had encouraged him to see a doctor. (The couple divorced after the trial.) In the end, Etienne pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity, which he would later come to believe started with the beating his brain endured in the ring.

There are sound and fair reasons why none of this softened Etienne’s sentencing, says Prem Burns. In court, the prosecutor represented the East Baton Rouge DA’s office, as she had across 34 years and 100-plus felony cases, taking down Medellin cartel members and serial killers alike. She recalls Etienne—“my, that huge wingspan”—and the trial clearly. “I remember the day he was sentenced. He said something like, ‘Ms. Burns, I’m so sorry.’ The drugs were just really bad for him.”

She believes that everything could have turned out worse for Etienne. Earlier in the afternoon of his robbery, she says, a local officer was killed in a drug bust gone wrong, and several more police were injured. The hospital where they were treated, and where fellow officers gathered, was near the check-cashing outlet that Etienne robbed—and so when the call came in to dispatch, the response was almost immediate. “Were this [in today’s climate],” Burns says, “he’d probably be dead.”

Burns remembers, too, the 9-1-1 call and the words Etienne barked out, recorded on security footage: “Im going to kill you!” She remembers using that against him in her opening remarks, and she remembers the jury convicting the boxer quickly and easily.

Years later, the prosecutor picks apart Etienne’s processing of the trial and the verdict. That he, a successful boxer, received insufficient representation? “The best criminal defense attorney in Baton Rouge would not have made a difference. Johnny Cochran couldn’t have gotten him off,” Burns says. That the jury may have been prejudiced against him? “He had an African-American judge,” she notes. “The clerk in the check-cashing place was African-American. So was [one of the men] he pushed from the car.” That no one was injured in the spree? “He’s not understanding,” she says. “If those shots had hit a car, or if that gun had gone off, he would probably be facing four counts of capital murder. He’d probably be on death row. There may be a difference in his mind, but there’s really no difference. His victims have permanent psychological damage they have to carry every day.”

***

In many ways, Clifford Etienne has been trying to tell his own story, paint his own picture, for decades. He remembers being 15, studying light and shading, copying other images, training himself as an artist. Today, he paints a portrait entirely unlike the one Burns holds up. A more complex rendering; nuanced. One altered by drugs and fame and celebrity. He renders his own likeness in the way he wants the world to see him.

“Painting to me is drawing with color,” he says. “And color has everything to do with painting. … Painting is what I intend to do when I regain my freedom. I go at it like I did boxing. … Put it all in there! … Since I don't box anymore, painting has taken over my life and future. It soothes my soul.”

Whether he’s distracting from the conversation about his past, or distracting himself, painting takes him away from the gun, the clerk, the kids in those car seats. He paints on canvas for income, and he paints over the worst parts of his story. He wrote early on about his small painting room, and then the space he shared with jewelry makers and woodworkers. About how he scraped together the cash for more supplies by selling dozens of paintings all over the world. To a professor in Austria. A boxing trainer in England. A dance instructor in New York.

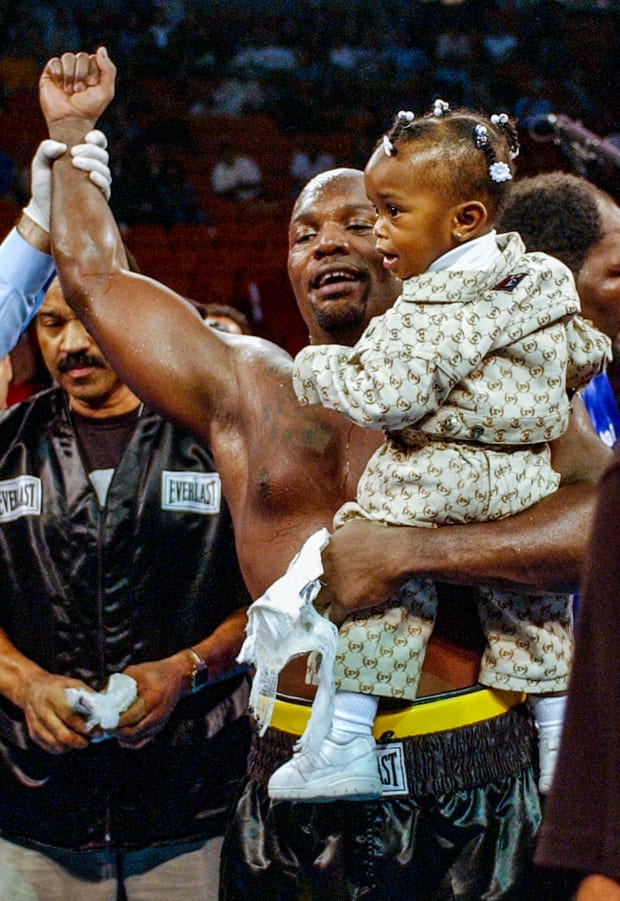

For over a year his letters focused on his art, and this pursuit seemed to bring him a sense of hope about his future. He began to believe, without reason, that he would be reintroduced into society, given a third chance. He saw his daughter, Jacol’e, graduating high school and aimed to help her through college. She reminded him of himself: a singer, an artist, a chef, a multi-tasker who does hair and plays sports.

He had plans. He would paint and sell and paint and sell. He would hold exhibitions, in galleries, not arenas. He would reunite with friends and family. Get himself in shape. Train young boxers. He clung to this hope with a desperation that made it difficult to splash cold water on his dreams.

***

The calm did not last. Etienne’s volume of work would ebb and flow based on how he felt on any given day about the resentencing hearing he sought, however unlikely that was. In his letters he came across as increasingly desperate. He began to focus on his brain, his believed CTE, and the defense that he thought would earn him an early release. He wanted to see a neurologist, hoping that a brain scan would reveal the chaos that he felt inside, and he wanted to put that in front of someone who could change his situation. He reframed his head injuries as exacerbating factors, as excuses; he believed, somehow, that they showed he was no longer a danger to society.

He started writing of headaches and dizziness, his struggles with balance and the Antivert medication he takes to combat what he described as vertigo. He said he couldn’t walk a straight line, and that he’s depressed. He said his mother, Emily, had discovered an old brain scan from after the Oquendo fight that already showed damage, almost 20 years ago. He pointed out that doctors diagnosed Aaron Hernandez with CTE after he hanged himself in prison.

Etienne: “I really feel for the football players, because I know they love the sport. I bet if they test any boxer that has been doing it for longer than 10 years they'd have CTE too! … It's too bad boxing doesn't have a representative association like the NFL, because billions of dollars would be coming out of the promoters’ pockets! They know how dangerous boxing is too!”

He wondered aloud whether prison officials were delaying the exam he sought, intentionally slowing the process. All the while he was stewing, languishing, deteriorating. In one email, from 2018, Etienne wrote that “the youngin’s are out of control!!” His quarters were increasingly cramped and he worried about his safety. He wrote about an inmate who stabbed him with a pen 25-odd times. About death’s inevitability. “I’ve seen many die in here and it’s sad,” he wrote. “Louisiana is a stupid place with stupid people.”

Weeks passed, then months, then years, his letters capturing an uneven descent. “F--- this place,” he wrote. “I'm f---ed up now. They took my pain meds from me.” Days later, he said he’d just been blowing off “steam,” and as the 2019 holidays approached he started painting again, seeing it as a kind of therapy. He started to cut hair in the prison barbershop and was mentoring a young boxer, who he wrote about glowingly. Then he was attacked again by an inmate, stuck with scissors.

Etienne: “I got into it with some [guy]. He stabbed me in the head. … The warden of security saw me after I was out of the ‘dungeon’ and told me I was too dangerous, dudes were too disrespectful … and I would end up killing somebody. He asked me how in the hell could I move so fast, and hit that dude so many times.”

Later, as the coronavirus spread, turning penitentiaries across the U.S., and especially in Louisiana, into hellish vectors of transmission, Etienne reported that his prison was locked down and that many services were suspended. Officials packed inmates closer together—“too close to each other all the time”—and Etienne said his bed frame was taken away, leaving him to sleep on a mattress atop the concrete floor. Another prisoner with whom he’d been isolated tested positive for COVID-19. Family visits were suspended indefinitely. Etienne said it felt like half the place was infected. He started to wonder whether he would die before his brain deteriorated.

***

Sometimes, though, his writings carried an unexpected, raw sensitivity, distracting from the dueling sagas of his battered brain and his life behind bars. He would pivot hard and spend a whole message writing about the influence of his most tireless advocate. As a trained nurse, Emily Etienne Robertson studied his old brain scan. As a concerned mother, she called the prison without end, whenever her son needed medication or felt mistreated. The top officials at Elayn Hunt Correctional Center knew her and addressed her by name. One day, shortly after Etienne finally got a bed frame back, the warden flagged Etienne while he was jogging. “Call your mother,” Etienne says the warden told him, joking that he heard from Emily more than he did his own wife. “Tell her you all have beds now.”

Etienne knows he isn’t the only one who has paid for his mistakes. He wrote: “I think about my daughter growing up since I left her at 5 years old. And I think about my mother who's been there when nobody else has ... and how much I'd like to give her everything she'll ever need in life. They need me, and I can't give up.”

***

This is what it looks like to rest your hopes and dreams on your own physical demise:

“Greg!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!”

Etienne could barely contain his excitement as he wrote about a visit, finally, with a neurologist who specializes in CTE. The aging boxer had failed a balance test, an eye test and pretty much every other gauge that could support his beliefs about his own deteriorating health. He told the specialist about one particular fight in which he’d been knocked down only once—or at least he’d believed for years that it went that way. Then he and the neurologist watched the replay, which showed one brutal fall after another, as if they were witnessing an entirely different match. Etienne wrote that he was trying to secure another resentencing hearing, where he planned to have this doctor testify about these findings. He described the tears of joy that streamed down his face as he thought about it all, pooling near his chin. He said the neurologist would help him get released. A lawyer was going to get the ball rolling.

All of which further muddied his picture, rendered murkier his ultimate goal. Across all of his writings, Clifford Etienne leaves unclear what he wants, or what he believes. Whether he takes responsibility for his actions. Whether he wants actual help—real remedies—for his maladies. He projects certainty only about where he wants to end up. Free.

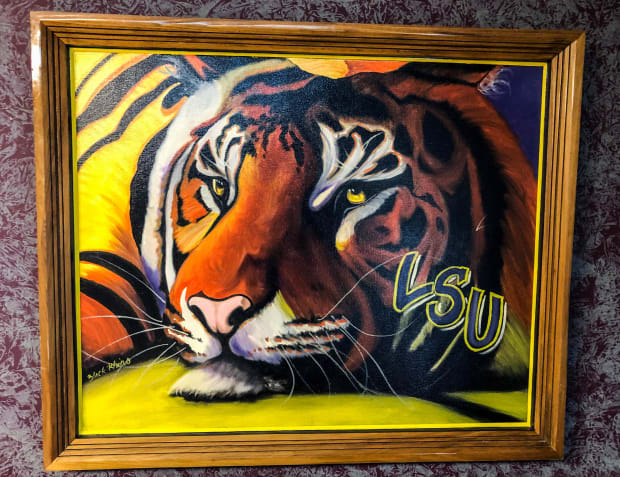

How? However works. There’s a lawyer with an office back in New Iberia, with a big desk and a painting of a tiger hanging behind it, signed by an artist who was once a famous boxer. The case that Richard Spears will lay out, if ever he is given the chance, is that Etienne is no longer a danger to society, that he is a positive influence on dozens around him, that he has served his time and rehabilitated himself. He has done everything that a man can do once he does something that cannot be atoned for, never erased. This isn’t the CTE defense, but in many ways it sounds more relevant to his client’s future freedom.

To the police officers that Etienne tried to fire at, to the man who still has nightmares about the day a heavyweight boxer tried to carjack his vehicle, Spears would say: Clifford Etienne has spent roughly half of his 50 living years in prison. He has apologized for his wrongdoings. He found a vocation and can earn income outside of a cell. He has taken classes on anger management and victim blaming, and while his letters don’t always square with those lessons, Spears says that they show his client’s efforts to change.

Etienne’s sentence, Spears argues, was too long to begin with, handed down by a judge who he says wanted to make an example out of a celebrity athlete; and that sentence didn’t factor in potential brain damage. CTE was not yet on anyone’s radar. “He’s entitled to a new sentencing with that as a major consideration,” Spears says. “It’s not his fault the science wasn’t there.”

Given the chance to argue Etienne’s case, Spears says he would introduce as a character witness the financial advisor who met with Etienne after the Tyson fight. Burke—now Deacon Patrick Burke—has grown to be a friend over the years, and he’s ready to tell anyone who will listen: Etienne’s sentence should be mitigated. Choosing his words carefully, he says: “I don’t think anybody meets Cliff and comes away feeling that he should spend the rest of his life in prison.”

Spears, meanwhile, says that his client is deeply, darkly depressed, and that he has been for years. He points to medical records that show several family members suffered from clinical depression. “His thought content, the speed of his thoughts, his reaction time—they’re all slower than just a few years ago,” Spears says. “It’s like his mind is aging very rapidly. I don’t know if that’s CTE, depression or just his [brain] condition worsening.”

Etienne hears these things and pleads with his lawyer: “Don’t let me die in here.”

***

Over the past few months, Etienne has veered back toward optimism. He moved into what he describes as a “trustee dorm,” where he says life is quieter and prisoners are more respectful of one another, and he is again painting every day.

“I'm good on this end,” he writes. “Only wanting peace … trying to perfect a craft that would make me millions. ... Painting can do it like boxing did the first time. … It’s so peaceful when I'm trying to create art that will make people stare at it for hours.”

In recent weeks Etienne built a makeshift guitar out of old, weathered wood. He painted B.B. King strumming on his own instrument, Lucille, and sketched Prince jamming on a purple axe. And he started working on oil paintings he was commissioned to execute for a collection of poems from the late Emma Wakefield-Paillet, the first Black woman to practice medicine in Louisiana. “I intend on painting a sketch I did of her headstone in a graveyard at night stuffed with tall moss-filled cypress trees. That'll be the back cover.”

Etienne is broken. His head hurts, his balance wanes and he worries that he will die, whether at the hands of another prisoner, or by his own, incarcerated. (“Sometimes I wish I could kill myself,” he wrote at one point, “and it'll all be over.”) He is also intact, though. He survived Tyson and two stints caged in the Louisiana swamps. He has endured, barely, the brutal business of boxing, multiple stabbings and a global pandemic. He says he tried, a few years back, to turn this all into a book. He’s certain it will all make quite a movie.

He believes that if he were tried again today, with all that science can now tell us about his brain, a jury would find him not guilty, by reason of insanity. He feels optimistic, as does his lawyer (who’s back on the case after a bout with COVID-19), that at some point he’ll see his sentence reduced. He looks ahead confidently enough that he imagines remarrying Tiffany—his “road dog”—once he’s on the other side. At various points he writes that “It’ll all work out fine.” And “I'm happy that this is almost over.” And “I'm so ready to get this thing started and over.”

After the latest attack, another inmate—a friend—encouraged Etienne to start dressing more neatly. Etienne listened. He shaved his head bald and started to exercise every day at 5 a.m. He stayed away, he says, from “rats, or dudes that would never amount to s--- in their lives.” Finally, the friend asked Etienne for a list of materials he would need to resume painting while locked in a cell, at that point, for 23 hours a day, on account of the scissors incident. Two weeks later the supplies arrived like magic: canvas boards, paint and brushes. The friend reminded Etienne: You’re the Black Rhino, the man who went from prison to the pinnacle of boxing. Eventually, Etienne returned to the painting room. Hearing or no hearing, he had to move forward.

So now he sits there, on hard concrete floors or on cold metal chairs, entranced, lost in imagined worlds, each one better than his reality. There’s no judge to assess his innocence, no doctor to evaluate his brain. No disappointed family (he says he hasn’t seen his mother or daughter in eight months, on account of COVID), but also no glory to revel in. He can paint positive portraits of lives well lived—the kind he wanted and the kind he had. This is what he clings to now: hours spent staring at blank canvases, and the glorious ability to fill them with whatever story he wants to tell.