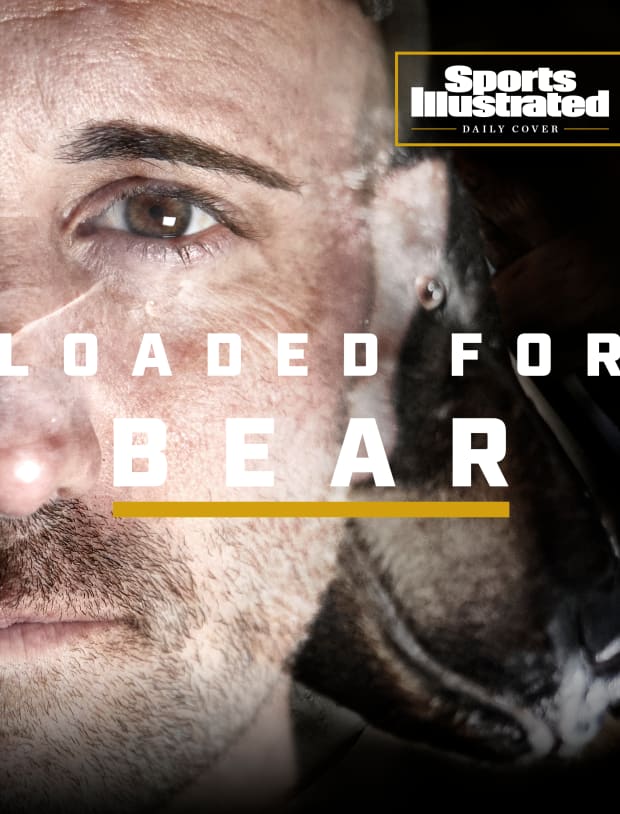

A bloody hunt. A ghastly attack. And a state divided on what to do about the black bears that humans encounter hundreds of times per year.

The 50-gallon drum, stuffed with a sticky mélange of molasses and croissants and doughnuts and birdseed and corn, sat in a secluded New Jersey swamp for more than a month with only two recurrent visitors. One was Jeff Melillo, a 46-year-old general contractor, who regularly stopped by to replenish the mass with mounds of doughy sucrose. The other was a 700-pound male black bear, with a white blaze across his chest, who habitually dipped his mammoth paws through a small opening in the vat of sweet, soft goodness, gobbling up whatever mess emerged.

For 30 days in September and October 2019, Melillo baited the behemoth to the site, not only with hundreds of pounds of pastries but also with blueberry and honey sprays engineered to target the bear’s hypersensitive snout. Careful to walk the same path in and out of the swamp, Melillo would leave his freshly worn shirt behind each day so that his musk would be associated with the pleasure of a free meal and not the peril that a human’s scent normally portended. It was all part of a daily dance the hunter had honed across a decade’s worth of trial and error.

By virtue of his intimidating size, the bear laid sole claim to Melillo’s food-stuffed barrel, sometimes even sleeping beside it, departing only to saunter over to a nearby spring for long drinks that helped him digest. He was nearly 300 pounds heavier than the average male black bear in the state, large enough that he warded off all competitors that visited the barrel in Kinnelon, an hour west of Manhattan’s wall of skyscrapers. Melillo, when he was away from the stash, received updates about the bear’s activities from a heat- and motion-sensored camera that he’d positioned nearby.

On Oct. 14, the first day of New Jersey’s then annual two-week bear hunt (the first week dedicated to bowhunting, the second to rifles), Melillo departed his home in nearby West Milford, hopped into his black Yukon SUV and made the 15-minute trek back to Kinnelon. Inside a case in the back of his truck rested the 18-inch Gearhead compound bow he’d spent the past few weeks firing from 20 yards into the rib cage of a bear-shaped target. Melillo had grown up hunting deer with his father, and he killed his first bear in 2003. Fixated ever since, he today owns a jacket bearing a dozen of the patches that his home state awards for each legally bagged bear.

In the late afternoon of a clear day, Melillo parked and set off into the woods—still mostly green, though some leaves were crimsoning. He walked the same path as always, spritzing the same sweet sprays in a wide circle around the bear’s adopted home, then settled 20 yards from the barrel, on a milk crate topped with a soft pad. The bow sat beside him, loaded with an arrow whose sleek, steel tip is promised by its manufacturer to deliver “maximum penetration” into flesh. With eyes fixed on the bear’s regular path back from the watering hole, Melillo waited.

What happened next has occurred more than 4,000 times in New Jersey alone in the past decade. What happened next, hunting advocates say, was essential to keeping that state’s nine million residents safe from its estimated 2,500 bears, with whom they cross paths hundreds of times per year.

What happened next, opponents of the hunt say, was unsporting and cruel and unnecessary, given just how infrequently bears wield their might against man. But, unquestionably, what happened next was violent. And painful. And gruesome. An interaction beset by blood and an anguished cry.

Five years before Melillo clutched his bow on that milk crate, Cassie Scott wanted to go for a walk in the woods. She was visiting her boyfriend, Owen McGreehan, in Bound Brook, N.J., and yearned for a little outdoors time before the next day’s four-hour bus ride home to Boston. Scouring the internet, she found Apshawa Preserve, 576 acres in northern Jersey—only a few miles north of where Melillo would set his bait barrel—including a web of loop trails that rank among the state’s most scenic.

The couple set off around 10 a.m. on Sept. 21, 2014, in McGreehan’s blue Jeep Compass, stopping first at a convenience store to load up with a breakfast sandwich, granola bars and an apple. When they pulled into the gravel lot of a trailhead, they encountered no signs warning about the prevalence of bears in an area that some locals referred to as Bear Swamp—only a map of the park. They shared a few nibbles of the sandwich, wrapped the remains in foil, stuffed it into McGreehan’s backpack and set off across the sort of lush terrain that gives the Garden State its name.

After following a gently sloping path, wandering into the late afternoon, they encountered a thick tree that had fallen across their trail and, a few yards later, the remnants of a bonfire, with trash and empty cans scattered about. Then the trail split: one route heading upward, the other on a decline. McGreehan ascended to get a better view while Scott followed the other path, down toward a small reservoir. A deer darted across the 40 yards of forest that separated them—leaves still mostly green, though some were crimsoning. Scott wandered to the water’s edge.

There, from out of the corner of her eye, she saw it, just 20 feet away: a black head, the size of a basketball, with a brown snout protruding and eyes that tracked her in still silence. “Owen, there’s . . . a . . . bear!” Scott screamed, bolting back up the trail.

McGreehan assumed his girlfriend was confused, that she’d actually seen the deer again, until he scanned the woods and spotted an animal with long claws and longer canines. Now about 50 feet from the bear himself, he slowly inched away as Scott scurried ahead of him. Eventually he caught up to her near the charred remnants of the fire pit, where they stopped to catch their breath and stifle their adrenaline, frightened but still intact.

Only 75 feet away, a male black bear—capable of speeds up to 35 mph, but not yet in full pursuit—trudged toward them.

What happened next is believed to have occurred just this once in New Jersey since it entered statehood in 1787. What happened next, hunting advocates say, demonstrates precisely why the state’s dense bear population needs to be continuously culled. What happened next, conservationists and animal rights activists say, might have been circumvented if the state had poured more resources into education, signage and trash management instead of leaning so heavily on the hunt to keep bears at bay. But, unquestionably, what happened next was violent. And painful. And gruesome. An interaction beset by blood and an anguished cry.

For Jeff Melillo, the reward from a month of baiting his target and studying surveillance photos would require just a little more patience. Finally, around 6 p.m., after a few tense hours sitting on his milk crate, salivating over the thought of breaking his friend’s state record for the largest black bear felled by a bow (as determined by skull size, that one measuring 22 9/16 inches), and with light from a setting sun streaming through gaps in the branches, Melillo saw his bear meandering back from its drinking hole. Positioned so he would have a clear look at the animal’s wide flank as it approached the barrel, Melillo drew his bow. The bear, long since aware of the hunter’s presence but comforted by his familiar musk, stopped and stared.

Melillo took deep, deliberate breaths, as he’d taught himself to do. He forced his heart to settle as the animal eyed him. “Everybody gets nervous,” he says. “I get calm.” His arrow cocked, held in place by a locking mechanism and trained on a soft spot just behind the bear’s left shoulder blade, all Melillo had left to do was squeeze a trigger.

Eyes locked on Melillo, the animal stayed unnervingly still, though a confrontation was unlikely.

“Any one of those bears above 100 pounds could kill you whenever they want,” says Gary Alt, who directed the Pennsylvania Game Commission’s black bear management program for almost a quarter-century. “And yet there’s only one or two fatalities a year in North America. Black bears are the most glowing example of an animal that has adapted well to people.”

In New Jersey, as the black bear population crept up from roughly 100 in the 1970s to more than 3,000 by the turn of the century, complaints began to multiply. Most came from citizens concerned about the beasts rooting through their garbage or gallivanting across their property. But since 2010, hunters across the state have slayed an average of 398 bears each year in the annual open season, and incidents of bears posing some sort of threat, by entering homes and tents or causing property damage, have reduced by more than half. Attacks have remained remarkably low: just six in the state across the past decade.

Today, says Jeff Tittel, director of the New Jersey Sierra Club, the old nuisance-bear problem is greatly diminished. Which would suggest that the hunt is obsolete. If anything, Tittel says, the adolescent bear “living behind your woodshed” is the problem—the one who’s going to become aggressive. By baiting and killing a bear “who’s been living in the middle of the woods for 15 years,” as Melillo did, “you’re not eliminating an aggressive bear, you’re just going after a trophy.”

When Melillo raised his bow, targeted his trophy and pulled the trigger, his arrow ate up the divide between man and beast in an instant. The steel tip entered the animal’s torso a touch higher than Melillo intended; still, the bear bellowed and growled, snapping its head toward the wound before thundering off into a thicket. Melillo listened for branches cracking in the distance, trying to gauge just how far his prey had run with a razor-sharp arrow lodged in its lungs.

Over the years he has heard other bears release a guttural death moan, a cry that haunts even the most seasoned hunters. “It’s a terrible sound,” he says. But he heard no such moan this time, so he packed his gear and returned to his truck, intent on gathering a few friends to help him follow the blood trail leading to his prize. While he walked the same path back to his vehicle that he always had, the agonized animal hemorrhaged, stumbling through the forest as the light faded.

Overtaken by fear and instinct, Cassie Scott bolted again when she realized that the bear—about half the size of Melillo’s—was marching up the trail behind her and her boyfriend. Owen McGreehan backed away, again, though now his pace quickened as the animal kicked into a steady stroll.

McGreehan caught Scott a few yards up the trail, though this time they didn’t pause. Soon they reached the fallen log, and here they realized they weren’t alone: Five college-aged men, most of them of slight build, trod toward them. None of them seemed to be dressed for a hike; they formed a collage of basketball shorts and sweatpants and T-shirts and sneakers, each carrying a small cinch-string backpack.

As boyfriend and girlfriend passed these seeming outsiders to the outdoors, Scott, frazzled, warned: There’s a bear. It’s following us. It might be 200 feet behind, just around a slight bend below. You should turn around. The panic in her voice and in her eyes seemed to register with the strangers. Still, they murmured about wanting to check it out.

“No,” Scott warned, “you don’t.”

The group left to consider that predicament consisted of four childhood friends—three young professionals: Prashant Patel, Zenas Lee and David Suh; and a Rutgers senior, Darsh Patel (unrelated)—plus Prashant’s little brother, Vishal. Just recently, Prashant had traversed coastal trails on a trip to San Francisco, and back home in Edison, N.J., he itched to re-create that experience. Like Scott, he had stumbled upon Apshawa’s network of trails online, and he hoped that day to lead his friends to the small waterfall that lay somewhere in its acreage. Earlier that morning they had packed their sacks with water bottles and granola bars and headed off from Prashant’s home, arriving at the preserve around noon.

After Scott’s warning, though, the friends huddled and weighed their options. Suh, the most experienced hiker in the group, insisted they not tempt fate, that they turn back. But the others marched down the trail, phones out, and soon the bear was in view. With the animal quickly closing the distance between them, instinct at last compelled them to turn around.

When a bear approaches, biologists warn, you’re best not to run. Speak calmly. Slowly back away. Keep an eye out for popping jaws or grunts or bluff charges; if the animal makes any of those threatening gestures, stand your ground. This particular crew of day hikers had grown up in a state replete with bears, but none of them appear to have absorbed those crucial lessons. Nor had they seen any trailhead signage warning them about the animals, or what to do upon encountering one—because no such signage existed. “We were being really stupid and curious,” Lee would later say. “[We] wanted to check it out.”

As the young men hustled away from the bear Suh heard Vishal say, from the rear of the group, “It’s chasing us,” punctuated with a nervous chuckle. Suh thought this was a joke—“We bust balls,” he later said—but when he turned he saw that Vishal wasn’t lying.

Now Vishal was running. And so was the bear. “It was galloping at us,” Prashant would recount.

A panicked trot turned into a full sprint. Suh darted left, off the trail. Vishal continued straight ahead. Prashant and Lee both cut to the right, while Darsh—at 5' 5" and 200 pounds, particularly quick to exhaust—fell to the back. As Suh ran, he turned and was confused by what he saw: Darsh, carrying one of his own black-and-red Reebok sneakers. The image concerned him. The two had grown up together, played lacrosse together, and Suh knew Darsh to be clumsy. “He’s never really been the running type,” Suh would later say.

Lee caught a glimpse of Darsh scrambling up a boulder, the bear within 40 feet of him. Darsh clung to the rock, either winded or injured—as his friends fled, none of them could tell. At some point, through harried gulps of air, he yelled: “Just go!”

The men ran at full bore, confused but rumbling through the forest, as Darsh faded from sight.

Jeff Melillo gathered a friend and a cousin, and, about four hours after releasing his bow, he and his crew reentered the swamp, hoping that the big bear had been allowed sufficient time to bleed out. The men fanned apart, scouring the dark forest, and quickly recovered an 18-inch portion of arrow that had snapped off as the animal fled, suggesting that some nine inches of carbon shaft remained embedded in its flesh. Nearby, blood dotted the ground, and close to that the inception of a red ribbon stretched into a 150-yard arc. The bear, it appeared, had started to loop back toward its adopted home beside the barrel.

Eventually, Melillo heard his friend let loose a high-pitched yip, a certain sign that he’d located the body. “You don’t want to wound [the bear],” Melillo says. “You shot it. You want to recover it. That’s your obligation as a hunter.”

Based on where he found the arrow fragment, and the spackles of blood across the forest floor, Melillo estimates that several minutes elapsed between the bear’s lungs’ being punctured and his eventual collapse. A grim demise, yes, but mercifully brief considering the alternatives. “Bowhunting is particularly problematic,” says Brian Hackett, New Jersey state director for the Humane Society. “Even if you hit [your target] for a kill shot, it could still take a long time for the animal to die. If you don’t hit them with a kill shot, they could be staggering around for days or weeks with a sharp arrow in their body. It’s incredibly cruel.”

Having tracked down their trophy, Melillo and his companions pried and rolled the carcass onto a sled, strapped it in, reeled the mass up to a Honda Pioneer UTV using a winch, dragged the beast out to the road and loaded it into a friend’s pickup truck, all over the course of four hours. In the morning, as required, Melillo drove the body to a check-in station manned by the state’s Division of Fish and Wildlife. There, workers logged the animal’s weight at 700.5 pounds. A taxidermist would later discover pellets buried in its hide (suggesting that perhaps it had once been scared off by property owners), but the technicians found no state-issued tags or trackers (meaning that it was unlikely to have posed a serious problem). Of the bear’s age, gauged to be roughly 10 years, one DFW official observed, simply: “He was in his prime.”

Back at his three-acre property, Melillo and a group of fellow hunters spent all day skinning and butchering the kill. Most vitally, they removed and cleaned the bear’s skull to determine its “score”—a tally used to track records. They detached the jaw and took measurements: one from the front teeth to the back of the skull; another laterally. Then they added those two numbers, for a total of 23 1/2 inches. Melillo was elated—he’d vastly outpaced his friend’s state record, by nearly an inch. Then he grew curious. He hopped online and was stunned to find that his was the largest North American black bear ever felled with a bow and arrow, eclipsing by 5/16 of an inch the record set in California in 1993.

Of the 41 states with black bear populations, 32 have legalized their hunting, with one weapon or another. (The hunting of brown bears, which are larger and generally considered more dangerous than their skittish cousins, is fully prohibited in the contiguous United States, where their population hovers around 1,000.) And the majority of those states permit baiting, which Alt, the Pennsylvania black bear expert, insists is an effective tool for locales that rely on hunting as a means of population control.

Is it sporting, though? Ethical? Before his death in 2020, Jim Posewitz, a prominent conservationist, explored that topic, and other issues surrounding hunting, in his seminal 1994 book, Beyond Fair Chase. There he observed that traditions vary by region. In some places chasing animals with dogs is accepted, while baiting is considered an unfair advantage for the hunter. In others, the inverse holds. “While local custom and practice need to be respected,” Posewitz wrote, “it is equally important to be honest about the result of these practices. If there is a doubt, advantage must be given to the animal being hunted.”

Melillo acknowledges that without bait he simply wouldn’t be able to locate and kill a trophy bear. But for him, the hunt was for more than a prize. Afterward, he stored the bear’s meat—a rarity in New Jersey—in a freezer. He gave away the bulk of it; with the rest, he made a massive batch of chili, sharing it among friends and family and members of the West Milford Junior Highlander Wrestling Club, of which he’s the president. “If you’re going to kill it,” he says, “you’ve got to eat it.”

After Melillo’s record kill was certified in February 2020 (at 23 5/16 inches, a smidge below his own measurement) by the Pope and Young Club, one of two record-keeping bodies that oversee all of U.S. hunting, he found himself bombarded with sporting swag, particularly from companies whose products he had used in his pursuit and had publicly endorsed in the aftermath. But he also got roped into the bigger conversation. Last October, after Governor Phil Murphy announced a goal of promoting “public safety and welfare while protecting New Jersey’s wildlife,” including striking the hunt from the state’s bear management plan starting in 2021, a national advocacy group, Hunter Nation, recruited the freshly anointed record-holder to help cultivate new members and start a chapter in New Jersey.

Enter a man who is prone to railing at length against “the antis” for being “uneducated” and “crazy.” (Melillo says he received death threats after his record kill made headlines.) He is indignant about his state’s plan to eschew the hunt while potentially pouring more resources into education and into the enforcement of trash management (which experts say is essential in keeping bears away from populated areas, reducing their interactions with humans). There has long been a bitter back and forth in New Jersey, with the hunt being stopped or started every few years. In 2018 pro-hunting advocacy groups took the state to court over a ban on hunting across state-owned lands, and the proposed bear-hunt ban is bound to instigate more legal wrangling.

Meanwhile, bear-related complaints in New Jersey were up 63% in 2020, which Tittel, the state’s Sierra Club director, attributes to people staying home and producing more garbage amid the pandemic. Whatever the cause, hunting advocates point to that uptick—and to the black bear attack last July on an 82-year-old West Milford man in his garage, necessitating 30-plus stitches—as the prime reasons the hunt should continue. However rare the incident, Melillo and his peers are certain that the shaken old man and the events that took place in Apshawa in 2014 are sufficient grounds to fire bullets and arrows into hundreds of bears each fall.

“They’re freaking nuts,” Melillo says of the hunt’s opponents. “You say that we don’t have a bear problem? I say, Bulls---.”

Zenas Lee and Prashant Patel surged through the woods until they realized they’d lost not only their pursuer, but also the three other hikers with whom they’d arrived. At 3:27 p.m., Lee called David Suh, who answered. Then Darsh Patel, who didn’t. Vishal Patel didn’t pick up, either, but he called back. Prashant dialed 911, and with terror in his voice beckoned police to Macopin Road, which serves as Apshawa Preserve’s eastern boundary.

“We should have stayed together,” Suh would later say. “We all should have just made sure everyone was O.K.” But they didn’t know that staying in large groups—especially groups of five or more people—significantly decreases the chances that a bear will attack. How could they have known? Two decades ago, New Jersey cut full-time positions for bear specialists, tasked with educating the public, and in 2009 slashed a more-than-century-old, once 100-member-strong deputy conservation officer program. Meanwhile, bear-related signage at trailheads was sparse. Had such warnings been delivered consistently, perhaps the group would not have approached the animal, phones out.

In the aftermath of the encounter, Suh and Vishal, shaken, found one another at a paintball field abutting the park, then convened with Lee and Prashant (none of whom commented for this story, and whose recollections are derived from public records) at a nearby deli, where they kept trying Darsh’s phone.

No answer. No answer. No answer.

Perhaps, Prashant hoped, the phone had been flung from Darsh’s pocket during a desperate escape. Whatever the case, these were the details with which West Milford police officers Denis Welch and Charles McQuaid set off in search of an endangered hiker: 22-year-old Rutgers student . . . Last seen carrying one of his own sneakers . . . Wearing blue sweatpants and a black T-shirt . . . And fleeing a black bear.

Once inside the park, the officers encountered college student Matthew Wilson, a frequent visitor to Apshawa, who offered his help. Welch discovered one of Darsh’s abandoned Reeboks; Wilson found the other, as well as a black pull-string bag resting down a hill. Then, from a ravine, around 6 p.m., Wilson shouted, a certain sign that he’d located the body.

Bears do not kill quickly. Preferring muscle to viscera, they often leave vitals untouched as they eat. During a fatal mauling, a bear will impose its weight and strength on its victim while gorging on limbs or hind quarters, a process that can stretch five or 10 minutes before death mercifully arrives. “It’s a horrible way to go,” says Alt.

In this case, the bear took an 11-by-8-inch chunk from Darsh’s left leg, severing a femoral artery. Upon discovery, his scalp bore another gash, half that size, and his skull was separated internally from his spinal column, suggesting that the animal had dragged him. One hundred forty-six deep puncture wounds and gashes pocked Darsh’s body. Scraps of his clothing lay in tatters in the vicinity. His phone remained tucked into a pocket of the blue sweatpants, which were caught in thorny bushes, but it still functioned, ringing and ringing and ringing in the forest while police and frantic friends dialed in vain.

As Wilson and four members of a search-and-rescue team (which by then was combing the woods) congregated around Darsh’s mangled remains, the assailant reappeared. Wilson, an avid hiker, was accustomed to seeing bears flee upon being spotted, but even as the humans shouted and waved arms and whistled, this one, he said, refused to stand down. Hearing that the rescuers were in peril, Welch retrieved a Remington 870 12-gauge shotgun and stormed back into the woods. In all, the confrontation wore on for some 30 minutes, and still the bear hissed and growled, so the officer fired off two rounds, the first one tearing through the animal’s right forelimb and ribs, and the second one smashing its jaw and teeth, pulverizing its nasal cavity. The bear took its final breaths just before the sun set and darkness fell over the park.

That evening, detectives broke the news to Darsh’s parents, an EMT stepping to Hemangini Patel’s aid as her world shattered. An investigation would later conclude that the bear hadn’t, in fact, been rabid; at 302 pounds it was undersized for an adult male, but it hadn’t been starving (which otherwise could have been a factor precipitating a rare attack on a human). Ample plant and animal remains were found in its digestive system. Still, the Department of Environmental Protection determined Darsh Patel’s death to have been the result of an exceedingly rare predatory attack. He marked the first (and still the last) person killed by a black bear in New Jersey’s 233-year history, and the 28th in North America—where that animal’s population is some 600,000—since 2000. Darsh’s outcome was, in the end, infinitesimally unlikely for a novice hiker who simply wanted to spend a day with his friends.

On Sept. 22, 2014, during her bus ride back to Boston, Cassie Scott planned to post pictures on Facebook from the hike she’d just taken with her boyfriend. First, though, she consulted the internet, to ensure that she’d correctly spelled Apshawa—and there, to her horror, Google’s search results broke to her the news of the hiker killed one day earlier by a bear, on the same path she’d walked. Instantly, Scott knew the victim must have been one of the five young men she’d encountered, strangers forever linked by a fallen log and a warning in the wilderness.

Six years later, Scott, 37, says she doesn’t want to see bears killed en masse, especially if state spending can reduce interactions like the one that still haunts her dreams. And on that front some progress was made in 2017, when New Jersey produced 6,500 placards for its 50-plus state parks, forests and refuges, warning hikers about the prevalence of bears and advising them on what to do in the event of an encounter. But for the most part, the Garden State has gotten less involved. The frequency of bear-safety seminars has dwindled, from 204 classes (and 24,000 attendees) in ’08 to 13 classes (and 2,000 attendees) in ’18. A state that spent nearly $2 million on bear management and education as recently as ’02 has since slashed that budget by more than half, eliminating full-time positions for bear education specialists and a training officer.

Critics like Hackett and Tittel look at the bear hunt in New Jersey and see a cruel stopgap, whereas less violent solutions, such as stringent trash management policies, have proved effective elsewhere, particularly at national parks across the West. The fight to preserve or eradicate bear hunting in New Jersey is fervent, but it isn’t uncommon: Similar battles have been waged in every corner of the country, from Florida to California to Washington to Maine.

In 2014, a young man and a black bear wound up dead, coming to rest 40 yards apart. Five years later, ostensibly for the sake of preventing the recurrence of such a gruesome scene, a second animal—one that had led a quiet life in a suburban swamp—choked down its last breaths while blood flooded its lungs. And now? In New Jersey, man and bear may soon be asked to peacefully coexist, an uneasy truce after unequal bloodshed.