Six years after Northwestern’s football team tried to form the first union in the NCAA, schools seem determined to play during a deadly pandemic, without any input from players.

As a linebacker at UCLA in the mid-1990s, Ramogi Huma was exposed to the absurdity of college sports when a teammate was suspended one game because an agent allegedly left $150 worth of groceries outside his apartment. For practically the rest of his adult life, Huma has been advocating for change on behalf of amateur athletes.

Today, he is the president of the National College Players Association, a nonprofit that aims to protect student-athletes from the whims of the NCAA. And he’s currently facing one of the biggest challenges of his career, as schools start to bring athletes back on campus in preparation for fall competition, in the face of a pandemic that in the U.S. may be growing, not slowing. Huma, who’s in constant contact with players across the country, is already preparing for the worst.

One football player, Huma says, recounted how a coach “explicitly told him that university leaders were using players as test cases. This player doesn’t want to be the test case.”

At another school, “a coach said, ‘We can have a lot of trial and error with the athletes, for when the regular students come.’ ”

And a third player says he was told by an administrator, “We’re going to get a lot of things wrong; we’re not going to be perfect.”

Says Huma: “There will be mistakes. … We just don’t know what kind of trainwreck we may be watching.”

Amidst a rush to reopen in the middle of a pandemic that has already taken 130,000 U.S. lives—and with no end in sight, thanks to a patchwork governmental response—sports leagues are taking advantage of a lack of direction so that they can resume printing money. The NBA is on track to finish its season in Florida, despite that state’s rising case count. MLB’s comeback was slowed not by the disease, but by team owners’ bad-faith negotiating over player salaries. And the NFL is quietly approaching the start of training camps, with very few indications that it is planning anything short of a full season. Then there’s college football.

Threatened by the loss of some $4 billion without a football season, the NCAA is pushing forward with its own mishmash plan to continue profiting off of unpaid labor. With the organization itself shirking the responsibility of drafting a universal set of comeback standards, individual schools, much like our states, are deciding on their own how to handle the pandemic, with seemingly every Power 5 team intending to play in the fall, one way or another. (The NCAA's chief medical officer, Brian Hainline, told The Athletic that he can make best-practice suggestions that schools can choose to adopt, but it would take months for the national governing body to pass sweeping legislation, and it can't mandate health practices in the meantime.) At Michigan, for example, athletes have to complete what is being described loosely as a 14-day pre-report risk assessment before a six-day resocialization period on campus. But at UCLA, players can report straight to workouts, where they’ll undergo routine temperature checks and practice social distancing. The results, so far, have been deeply concerning, including small outbreaks at Alabama, Clemson, Houston, Kansas State, LSU and Texas, among other schools.

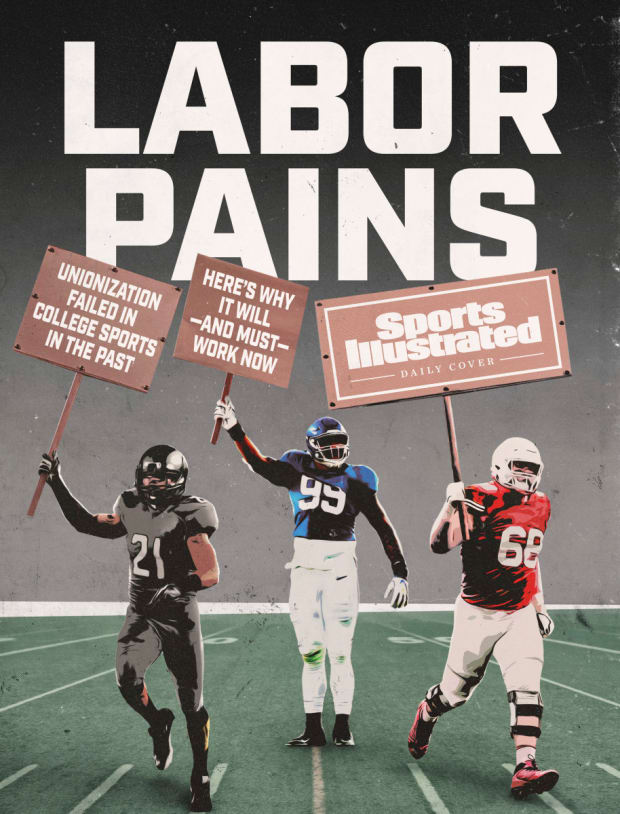

As schools make decisions that could profoundly impact the lives of their athletes, with little or no input from those athletes themselves, college football players are plainly lacking the key mechanism that protects their professional counterparts: A union.

***

Twenty years after Ramogi Huma graduated, little has changed at UCLA, or across college football. Elijah Wade was a freshman defensive end for the Bruins in the spring of 2019 when he started feeling a lingering sensation in his left hamstring. A cog in coach Chip Kelly’s first recruiting class, Wade knew his body didn’t feel right, and he brought it up, repeatedly, to whoever would listen. According to Wade, he raised concerns to his position coach, a strength and conditioning coach and team doctors, trying to get his workouts adjusted or his treatment tailored to suit his problem. But his worries went ignored.

“For six days,” he says, “I yelled and screamed—and nothing was being done. We get to the end of the week, and guess what happens? I pull my hamstring.” (In an email, UCLA declined to address the specifics of Wade's injury, but a spokesperson wrote: "The health and welfare of our student-athletes is always our top priority.")

Wade’s story is hardly novel, or even considered particularly explosive, which is part of the problem. It is, though, an indication of the power dynamics in college football. A player can raise concerns all he wants about an issue within his program—physical, mental or otherwise—but the NCAA largely asks those schools to police themselves, and universities routinely abdicate that responsibility in favor of maintaining the status quo.

Case in point: Entering this offseason, Iowa’s Chris Doyle was the highest-paid strength and conditioning coach in college football, earning $800,000 a year. He also had—based on allegations made in June by a group of former Hawkeyes—a history of mistreating his charges during his tenure. Doyle, who began leading Iowa’s strength program in 1999, has been accused of treating Black players differently than their white counterparts, allegedly threatening to send one player “back to the ghetto” and another “back on the streets.” But it wasn’t proactiveness by the university that led to Doyle’s parting ways with the program on June 15; instead, it took a national conversation about racial injustice and police brutality, which led former players to finally feel comfortable speaking publicly about the culture at Iowa. Even then, Doyle (who denies making any racist comments) refused to apologize as he departed, and he’ll receive a hefty severance package for walking.

For 20 years, Doyle’s behavior went unchecked because players were too scared to speak up—or, if they did, said they were silenced by a coaching staff that held all the power. It’s against this familiar backdrop that universities—with decision-makers who routinely act against the best interest of athletes—are now being asked to look after the health and safety of players through a seemingly unending pandemic. (Some schools have already sidestepped that responsibility altogether by asking players to sign waivers removing any university liability in the event of illness.) There’s no universal health and safety standard for every coach putting his players back on the field, and there’s very little trust among advocates that the people in charge will uphold any standards put forth.

“What are the safeguards?” asks Huma. “And will they be enforced? It does not matter what a school promises. ... They regularly violate health and safety practices, which has led to negligent deaths, sexual assaults and a lot of issues for college athletes.

“Other sports have labor law; leagues have to negotiate with unions. [Those athletes] have a mechanism so that they can’t be isolated or coerced into taking risks they are not comfortable with.” College athletes, though, “are workers without workers’ rights.”

That notion is hardly a new one.

***

It was at a Chicago steel mill in the summer of 2013 that the seeds were planted for the first serious attempt at unionizing college football players. Kain Colter, in the summer before a senior season in which he was one half of Northwestern’s two-headed quarterback platoon, was on a class outing when the parallels between college players and steel workers (who’d lacked health and safety protections before they unionized) struck him. Afterward there was a discussion about how unions can improve conditions for workers, and Colter took the initiative to contact Huma, with whom he discussed the impact that collective action could have in helping college athletes.

After months of discussions, and after the QB finished his senior season, Colter and Huma pitched Northwestern’s football players in January 2014 on the idea of unionizing, and a majority of them signed union cards. The NCAA, meanwhile, swiftly condemned the plan, and the university announced it would not recognize the union, setting the stage for a contentious court battle in front of the local chapter of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), the governing body with jurisdiction over labor issues at private institutions.

Colter’s testimony—about how his football schedule restricted his ability to choose classes, about how difficult it was to stretch his monthly stipend to cover expenses, about the extent to which his activity on social media was monitored—cast college athletics in a negative light, and it put him in the crosshairs of his own school officials, including coach Pat Fitzgerald, who testified that the school let athletes put their classes before football and rarely exercised its powers to remove players from their scholarships.

Northwestern’s players won that ruling at the NLRB’s regional level, but the school appealed to the national board. In the meantime, Fitzgerald opined publicly against his players unionizing, and Northwestern’s athletic department warned that a union could lead to the canceling of all the school’s other sports. Former football players reached out to discourage the team from following through.

In April 2014, one day before Colter’s old teammates would cast secret ballots as part of NLRB procedure on whether they wanted to certify the proposed union, he spoke out about all the pushback. “For guys on the team,” he said, “this is no longer about having a voice. I’ve heard concerns, like we won’t get jobs, alumni won’t donate, coach Fitz might leave. … None of that has to do with having a voice. … There’ve been so many variables added to the puzzle that shouldn’t be.”

In August 2015, the NLRB declined jurisdiction on the case, in part because of the complications of having only one school in the NCAA unionized. In effect, the plan fell apart, though the door was left slightly ajar for a group of athletes to repeat the process in the future with a larger coalition. While the result of the ballot remains sealed because the NLRB bowed out, Colter believes to this day that his teammates, under pressure from the school’s union-busting campaign, voted no. (In the days leading up to the vote, a Northwestern spokesman said the school had acted within NLRB parameters.)

“I don’t regret the union action, or everything we were trying to accomplish,” says Colter, who by the time of that ruling had already gone undrafted and spent a season on the Vikings’ practice squad. (He would also spend training camp with the Bills in 2016.) Nearly five years after the ruling, he says, “[Our efforts were] well-intentioned. It wasn’t a grudge against the university. We wanted to increase democracy and participation in collegiate sports, and that starts at the local level, at the institution we were a part of.”

If the NCAA didn’t change its course, neither did Colter, who for the past three years has followed his passion for workers’ rights. He took a job in 2018 with the U.S.’s second-largest teachers union, the American Federation of Teachers, where he campaigned in Wisconsin for politicians hoping to combat Republican governor Scott Walker’s antiunion legislation. After Tony Evers, a Democrat, unseated Walker, Colter moved on to Iowa, campaigning on behalf of Joe Biden in late ’19 in the leadup to the Democratic caucuses. Most recently, he worked in Colorado for the Working Families Party, where he drafted campaign messaging for pro-labor policies like raising the minimum wage in Denver.

He’s had sparse communication, meanwhile, with his old coach, and he hasn’t been invited back to Northwestern in any official capacity despite in 2013 leading the Wildcats to their first bowl win in 60-plus years. He ties all of this to his unionization bid, but he still believes the fight was worth it.

Since then, Colter points out, “there have been some pretty significant concessions from the NCAA,” including a bill passed last September in California—which Huma and the NCPA lobbied for—allowing athletes to hire agents and profit off their name, image and likeness. “There has been some pressure through the courts and collective action, and some legislation drives have been successful.”

Even in failure, Colter’s union push did lay the groundwork for what to expect from a future attempt. Players will almost certainly have to combat a union-busting campaign. There may be some hurt feelings and tense relationships. But it also set a precedent, that college athletes could be considered employees.

***

To understand the importance of unions in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, one simply has to look at the professional sports world. While the ethics of the NBA returning in late July are up for debate, that return comes only after robust discussions between the league and its players association, whose president, Chris Paul, dealt personally with commissioner Adam Silver. Inside that union there has been dissent about a comeback, and some concern that basketball might distract from the ongoing protests against police brutality—but those voices have been heard and, if players return, they will have made the NBA engage in discussions regarding social justice. In baseball, players used their bargaining power to prevent MLB owners from skirting an initial agreement to pay prorated salaries based on the number of games played. In the end, they could not be unilaterally forced to play under conditions they deemed unworthy of the risk.

College football players do not have the same protections, yet they’re being called back to campus, and those who choose not to play do so without any NCAA plan to ensure their scholarships are preserved.

“If decisions are going to be made on whether there will be a season or not, how could [that process] not include the voices of the people on the field?” asks Wade, who left UCLA’s football team after his sophomore season but remains enrolled and is now trying to fight for his former teammates as a member of the school’s student council. As a representative, he passed a resolution calling for the school to protect athletes during the pandemic with a third-party overseer, and for student-athletes to have an official role in all discussions regarding return-to-play plans.

Unionization would ensure just that, making players an active part of the return process. It would also give them a say in how schools handle their safety once they’re on campus. Without it? “There are zero ways to address abuse,” says Huma.

To prevent the worst in the short term, Huma is lobbying for local governments to hold schools accountable during the pandemic, calling for those offices to punish universities that violate health and safety standards set by medical experts. But when it comes to individuals making decisions, unchecked? He has little faith.

Coaches, he says, “are pressuring trainers and doctors to put players back in action when they shouldn’t be. Now what’s going to happen when your star player wakes up with a fever or a cough on game day?”

***

There’s evidence that college athletes are already realizing the power of collective action, from the group of 30 UCLA football players threatening to sit out booster and recruiting events if a third-party outfit isn't installed to oversee their workouts and ensure their health, to the collective at Texas that made a similar threat if the school failed to make its campus more inclusive for Black athletes.

Could this all add up to another union push? Perhaps, but there are new complications. After Colter’s bid, Ohio and Michigan passed bills disallowing college athletes from being classified as employees. And the NLRB is currently made up of all Republicans, who have historically been unfavorable to unions. Colter, though, sees a way forward, particularly if Biden wins the presidential election—and the ability to mold the NLRB—in November.

When the board declined jurisdiction on the Northwestern case, it noted that unionizing one school wouldn’t stabilize labor relations across college athletics. Even if Northwestern’s players had earned the right to collectively bargain, they still would have been beholden to conference and NCAA rules. Colter thinks, though, that if a new coalition of athletes formed across schools and conferences—and listed, say, the Big Ten or the NCAA as their employer—they might have a better case. (As for those states with specific legislation preventing student-athletes from classifying as employees, they could be pressured to adapt if other states allow unionization, presenting a sort of recruiting advantage. After California passed a bill allowing student-athletes to profit off their name, image and likeness, several states followed suit, often with bipartisan support.)

In short, college football players need to build a bigger coalition. Wade, like Colter before him, is beginning at the local level to increase participation. He’s also outspoken about the culture of college football as a whole, and he’s in touch with players from other schools with their own concerns. Could Wade be the person who leads the next union drive?

The effects of the pandemic and the fight for racial equality have “really exposed the hypocrisy in a lot of systems, college athletics especially,” he says. “You have a system of fear and power dynamics that’s being used to stomp out the voices of these athletes. There is a need for some type of union. As of now, student-athletes don’t have anything.

“They don’t have a way to say, ‘Hey, do you hear us?’ ”