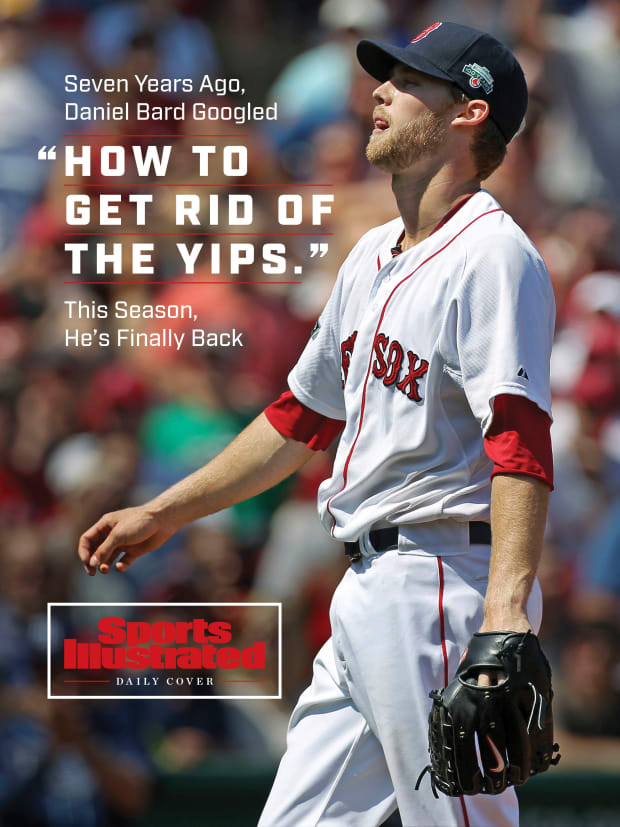

Baseball's most mysterious ailment completely derailed the former Red Sox flamethrower. He's finally found his way back to the big leagues.

Five months ago, Daniel Bard ascended a pitcher’s mound and waited for the monster to return. It had been seven years since his last major league appearance (nine pitches, eight balls), three years since his last minor league appearance (eight batters faced, five walks, two hit batsmen) and a lifetime since he last enjoyed baseball.

From 2010 through most of ’11, Bard was the most unhittable pitcher in baseball. Then he contracted baseball’s most mysterious ailment: the yips. Slowly, and then all at once, he lost the ability to throw the ball over the plate. No one knows exactly what causes the yips or how to cure them. But everyone agrees that they are usually fatal to a player’s career. Once you lose the ability to do the simplest thing in the game, it’s almost impossible to get it back.

By 2012, Bard was drifting from one minor league complex to the next, hurling baseballs over the backstop, unable to find the catcher’s mitt. He finally put his career out of its misery in ’17. A year ago, he was quietly making up excuses not to play catch with his two toddler sons. He didn’t want to introduce them to something that had caused him so much pain, says his wife, Adair. “He didn’t want [them] to have to experience that.”

Now, at 35, he was back where he began, standing on a high school mound and staring into 25 radar guns, trying to persuade a major league team to take a chance on him. If the yips were going to resurface, he realized, now would be the time.

***

In September 2011, Bard walked nine batters and hit one in 11 innings. He blew three saves and took the loss in two more games. His struggles were overshadowed by those of his team—the Red Sox went 7–20 to let their 1 1/2–game division lead evaporate—but he knew something was wrong. Later he learned he’d had an undiagnosed case of thoracic outlet syndrome, a compression of the nerves or blood vessels in the space between the neck and the first rib. But at the time, all he knew was that he couldn’t put the ball where he wanted it.

In the wake of Boston’s disastrous finish, GM Theo Epstein and manager Terry Francona resigned. Their replacements, GM Ben Cherington and manager Bobby Valentine, decided to spend the following spring stretching out Bard as a starter. The coaching staff tinkered with his mechanics. The physical issue mushroomed into a mental one. And the more he tried to fix it, the worse it got.

He knew there was a name for what he had. But he couldn’t bring himself to say it. Many players feel the same way. They refer to it as the thing, or the monster, as if calling it by its name might summon it. “I called it a throwing issue for a long time,” Bard says. “You’re reluctant to use that word.”

He didn’t want to speak it aloud. So in 2013, he typed it into a Google search bar: “How to get rid of the yips.”

***

He tried everything. He switched to a sidearm delivery. He worked with a specialist in tapping, a therapy in which the patient touches his fingers to certain pressure points while talking through trauma. He lifted weights until his arms gave out, hoping he would be too tired to overthink his motion. He gulped two beers before bullpen sessions, just to take the edge off. He visited three different hypnotists.

A year ago I was one of the best pitchers on the planet, he thought. Now I’m having a hard time playing catch, but my arm feels fine. Is my diet messed up? Do I have a brain tumor?

Whatever was wrong with him was his fault, he decided. He had incredible talent and dedicated coaches. People expected him to be great, and he was capable of greatness. He should be great. He must not be trying hard enough. You’re a failure, he told himself.

“That’s the closest I’ve felt to losing my mind,” he says now.

While Daniel was tapping, Adair was packing. Daniel walked 27 men in 15 1/3 minor league innings in 2013. The Red Sox designated him for assignment. He played winter ball in Puerto Rico that offseason. He walked nine and hit three in 1/2 of an inning. In ’14, he signed with the Rangers. He walked nine and hit seven in 2/3 of an inning at Class A. In ’15, he signed with the Cubs and spent six weeks doing throwing drills in the batting cage, then six months on the injured list. In ’16, he signed with the Pirates and stood on back fields at their complex in Bradenton, Fla., trying to guess where the ball would end up. That May, he signed with the Cardinals. He walked 32 and hit seven in 11 2/3 innings at High A and Double A. In ’17, he signed with the Mets, who tried to turn him into a submariner. He walked five and hit two in 2/3 of an inning in rookie ball, playing against teenagers. He was 32.

Adair watched as his shoulders, once broad and straight on the mound, began to slump. She grimaced as he berated himself. She cringed as fans in the stands booed. In the tiny minor league ballparks, she heard every heckle. “Is that Daniel Bard?” someone said once. “I can’t believe he’s still playing.” In 2013, the Red Sox demoted him all the way to the Lowell (Mass.) Spinners, in Low A. He walked four in one inning. The fans were so vicious that Adair rushed out of LeLacheur Park so no one would see her cry.

She grew so used to the releases that the last two times they came, she had the boxes out before Daniel called to tell her. He had taken too long to check in after a workout. That could only mean one thing. “It’s not like I was expecting the worst,” she says, “But I started being prepared for the failure.”

He thought he was prepared for it, too—because he’d been through it before.

***

Bard all but swaggered into Red Sox camp in 2007. He was 22, Boston’s first-round pick out of the University of North Carolina, a lanky right-hander who could hit 100 mph so effortlessly that Francona, watching from the side, assumed he was throwing 93. So Bard was taken aback when coaches shifted his arm slot higher.

“I got really aware of my movement,” he says. “Nothing was free and easy like it had been my whole life.”

He didn’t call it the yips then. He calls it the yips now. He walked 22 men and hit one in 13 1/3 innings at High A Lancaster (Calif.). A demotion to Class A Greenville (S.C.) did not help much: 61 2/3 innings, 56 walks, seven hit batsmen. To outsiders, he seemed to be working through a mechanical issue. He knew the truth: He was in trouble. The Red Sox saw it, too. They sent him and Double A pitching coach Mike Cather about as far away as they could get, to a winter league in Hawaii, and told him to pitch out of the bullpen.

Cather’s diagnosis came quickly: “He cares too much,” he says now.

So Cather set about getting his protégé to think less. He lowered Bard’s arm slot back to three-quarters. He had Bard scrap his changeup and focus only on his powerful four-seam fastball, his two-seamer and an occasional slider. They threw long toss until their arms burned. All power, no finesse. “Hey, man, we’re throwing it in this direction,” the coach would say.

Bard pitched 16 2/3 innings in Hawaii. He walked 15 men and hit five. But he felt cured. A few games in, he beamed at Cather. “This is the first time my mind has been clear in a while,” Bard said.

The next season, in 2008, he walked 30 and hit six in 77 2/3 innings across High A and Double A. A year later he debuted in Boston.

***

Bard had recovered from the yips once. He felt sure he could do it a second time. But this bout threatened to cost him more than his career. It was beginning to cost him himself.

Adair used to tease him that his confidence bordered on cockiness. He would just grin. Now the self-belief was gone, and so was the smile. Daniel would lie awake at night, obsessing over his mechanics. What can I do tomorrow that’s gonna be different than today? he would think. Because today sucked. He began drinking more heavily in an attempt to quiet his mind.

“I was like, I’ve gotten through this before. I can do it again,” Bard says. “But I was putting way too much pressure on myself to allow myself to do it again.”

Finally, in August 2017, he took the mound at the Mets’ Port St. Lucie (Fla.) facility for a bullpen—just Bard, the catcher and the mental skills coach. Adair was back home in Charlotte with their 18-month-old, Davis. Daniel would sometimes go weeks without seeing them. He barely recognized Davis, so much had the child changed. He felt like fatherhood was the only job he was any good at, and he wasn’t doing it.

He threw half a dozen pitches. Most missed wildly. For the first time in his life, he cut a workout short. He flipped the ball to the mental skills coach.

“I don’t want to throw anymore,” he said.

He meant that day. But as he drove away from the park, he realized he didn’t just mean that day. I don’t want to throw anymore, period, he thought. He burst into tears. But he didn’t feel regret. He felt relief.

“Everybody has that fear of retiring,” Adair says. “What does life look like without this huge thing we live our life around?” She pauses. “We learned that it’s actually wonderful.”

For a while he convinced himself that he needed to find the perfect next career and excel at it. A friend suggested he just try to pick a job he might like and see where it took him. At first he wasn’t sure he wanted to have anything to do with baseball. But he had learned a lot about the mental side of the game, and even though it hadn’t fixed him, it felt selfish not to share his knowledge.

At one point with the Cubs, he had walked the bases loaded in a B game. He returned to the clubhouse to find an anonymous note in his locker: You don’t know how much respect we all have for what you’re continuing to battle through. You’re gonna get through this one day and we’re all gonna have a big party. He never found out who left it. As he got older, he was sent to increasingly lower levels, so his teammates got younger. At Double A with the Cardinals, prospects would come up to him and ask how he threw his slider.

Did you see my outing yesterday? he’d ask. Why do you want my advice?

Your slider’s nasty, they’d say. How do you throw it? Also, do you think I should marry my girlfriend?

He realized he could maintain the relationships he had loved so much without having to worry about his own performance. When the Diamondbacks offered him the role of player mentor and mental skills coach, he accepted it.

He worked with players at all levels of the organization. He told his story hundreds of times. As he retold it, he started to tell it differently. Maybe he wasn’t a huge failure who deserved scorn and derision. Maybe he was a guy who had a good career and then battled a monster almost no one slays.

Bard wanted to build relationships even with players who weren’t yet struggling so they would trust him when they were. So he started taking them to the place they felt most comfortable, the field. And he started playing catch.

Three different pitchers told him how well he was throwing. “He wasn’t warmed up or anything,” remembers Diamondbacks lefty Alex Young. “It was coming out hot. I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, dude, you’ve still got it!’ [The throws hit] the chest every single time. ... We kept saying, ‘Dude, you should try out!’ ”

Bard laughed. “It doesn’t count,” he insisted. “We’re just playing catch.”

But his mind began stirring. It wasn’t just that he was throwing well. It was that he was feeling something he hadn’t felt on a baseball field in nearly a decade: joy.

He and Adair talked through the logistics of a comeback. Davis is now four, and they also have two-year-old son Sykes and eight-month-old daughter Campbell. Adair once removed Davis from a ballpark so he wouldn’t hear what the fans were saying about his dad. She was worried about how people might react. But they also loved the lesson the kids would learn about perseverance.

He spent the winter throwing bullpens with his brother, Luke, a right-hander with the Angels. Daniel found himself hitting 96 mph consistently. And he knew where it was going. In February, he quit his job with Arizona. Five days later, he climbed the mound on that high school field, and waited for the monster. It never showed up. He started laughing.

***

The Rockies signed him later that week. On Friday, they told him he had made the Opening Day roster.

This still might not work. Bard knows that. He feels good now, but he felt good the last two times the yips showed up. At any moment he could lose the strike zone again. But this time, he knows, he would be O.K.

“I think I just view life in general a lot differently at this point,” he says. “When I was younger, I felt like you have to follow this path of success. It’s what we preach in America: Know what you want to do, find that career, perfect it. Through my struggles I realized life is a lot less organized than we give it credit for. The world is the same way. If this pandemic shows us anything, it’s that it’s all pretty fragile. The stuff that matters is relationships and how you raise your kids. … I have to keep reminding myself of that daily. This opportunity with the Rockies is really cool, but it’s not gonna be permanent. Hopefully it lasts five years, but just enjoy it daily.”

The irony tickles him. He got baseball back just as soon as he stopped needing it.