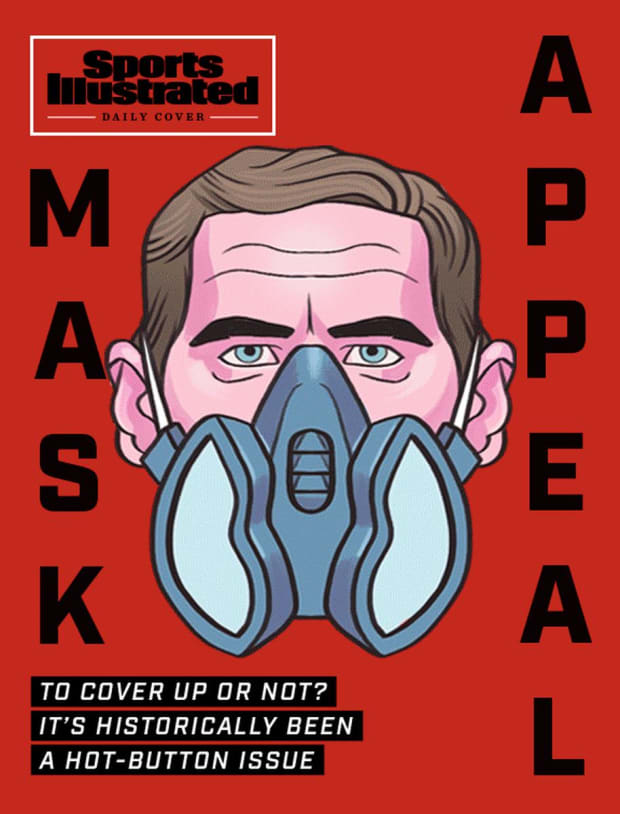

This pandemic is hardly the first time we've been asked to cover up for safety. And it's hardly the first time there's been significant pushback. Just ask catchers and hockey goalies and ...

Masks are emasculating and uncomfortable and infringe upon personal liberty.

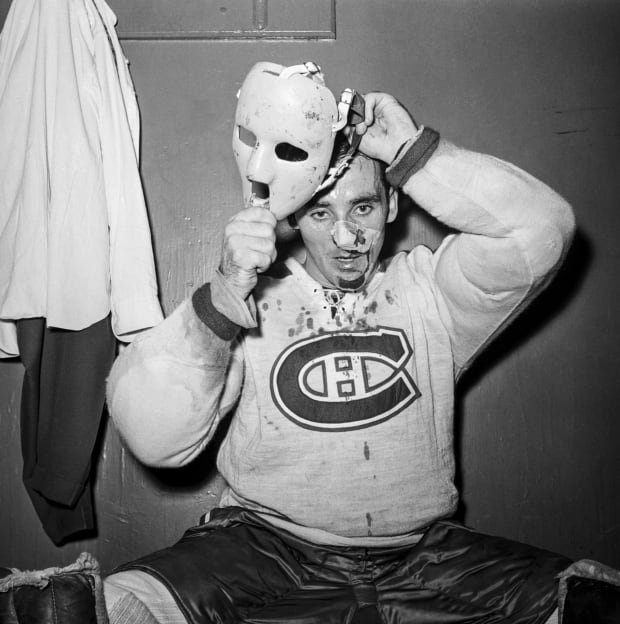

“I thought he was a wimp,” Black Hawks goalie Glenn Hall said of Jacques Plante, who donned a mask in goal for the Canadiens the day after Halloween in 1959 at Madison Square Garden. There, the Rangers’ netminder, Gump Worsley, said a mask would obscure the puck at his feet. “I won’t wear one,” he vowed, to the approval of New York general manager Muzz Patrick, who thought masks robbed the crowd of some natural entitlement. “The mask takes something from the fans,” said Patrick. “They want to see the man.”

Montreal coach Toe Blake gave Plante permission to put on the mask in the first period that night at the Garden, after Plante’s unmasked nose was nearly shorn off by a shot from sniper Andy Bathgate. A long delay ensued, during which time Blake knew that his unappealing alternative—in those days when NHL teams carried only one netminder—was to use the Rangers’ “house goalie,” a sentient version of the soup-stained house jacket that formal restaurants lend to men who turn up at the maître d’ stand bereft of a blazer.

Until that night Blake had allowed Plante to wear a mask in practice but not in games, where drunken crowds in drafty arenas would ridicule him. “To [Blake], a goalie who wore a mask was betraying a fear of the puck and was showing signs of cowardice,” wrote Todd Denault in his absorbing 2009 biography, Jacques Plante, whose subtitle—The Man Who Changed the Face of Hockey—is a spoiler of sorts: In hockey, goalie masks became a staple of personal protective equipment, despite the objections of respected men whose names—Muzzy, Gump, Toe—now read like a Canadian analog to the Three Stooges.

A few weeks after Plante wore his mask Bruins goalie Don Simmons donned one of his own for precautionary reasons, and one-by-one in hockey the antimaskers dropped their objections, and their bravado. College hockey coaches had molds taken of their netminders’ faces, then had them fitted with fiberglass masks. “Every boy should be forced to wear one,” Boston College coach John Kelley said. Lower youth leagues made them mandatory. “This new mask, I’m sure, saved one eye for one goalie this week,” said the director of the Minnesota bantamweight hockey tournament in 1962, when masks were not yet compulsory there. “One of the boys caught a puck smack in the optic. It did no damage.”

Plante had shattered both cheekbones in goal, suffered concussions, broken his nose and had a face so frequently stitched that it was practically a work of needlepoint, a medieval tapestry of a Catholic martyr. Crucially, Plante didn’t care what others thought of him at a time when masking up and manning up were mutually exclusive activities. He spent his time on trains reading, writing and knitting his own goalie undergarments. In a reversal of the popular perception, Plante was a professional athlete who aspired to be a sportswriter. By the time he wore his mask in that fateful game in New York, six full seasons into his NHL career, the 31-year-old Plante was certain that masks saved lives, or at least saved goals, and that wearing one would prolong his own working days in hockey. “I hope that with the mask I can play until I’m 40,” said Plante, whose example might even serve as a parable for our own turbulent times.

***

Hockey is hardly the only North American subculture in which masks were not considered masculine. The so-called “mask slackers” of the 1918 flu pandemic were legion, and many went to jail or incurred fines rather than wear a facial covering. When the Red Cross shipped 10,000 masks to Oklahoma during the Dust Bowl, locals scoffed. A wire-service reporter traveled to Guymon in 1935 wearing a dust mask, which he soon discarded in favor of a cowboy hat. “If you don’t want to be called a sissy,” he concluded, “pass up wearing a dust mask in the Oklahoma Panhandle.”

And so it has gone in American sports. Personal protective equipment, from batting helmets to cups, gets ridiculed, resisted, then widely embraced. Harvard baseball player James Tyng wore a catcher’s mask, created for him by team captain Fred Thayer and modeled after a fencing cage, during a game against the Boston Red Stockings in 1877. “The spectators were universally amused, and wanted him to ‘take off the muzzle’ and ‘try it without a bird cage,’ ” said George Wright, Boston’s Hall of Fame shortstop. Wright was speaking in 1886, by which time the catcher’s mask had become a universal piece of baseball PPE, with 12,000 sold annually, many of them by his sporting goods firm, Wright & Ditson. “I saw at once,” Wright said, “that it was a good thing.”

During World War II, when gas masks were distributed to civilians in the U.S. and the U.K., the Air Force basketball team at Maxwell Field in Alabama scrimmaged in the cumbersome contraptions, to grow used to them in case they were needed in battle. Running a fast break in a gas mask in 1942 was more onerous than wearing a cloth mask into Costco in 2020, and yet, said Lieutenant Robert Goldstein, who coached that team, “The men have a lot of fun [with] it.”

Football face masks were uncommon in the 1940s, mostly used by a player nursing an injury. That masks could also prevent injuries was a novel concept. But even beyond Plante, the ’50s would become a golden age of masking, when The Lone Ranger was among the most popular programs on the new medium of television. “I’m going to continue to wear my mask,” the title character told his sidekick, Tonto. “Our job has just begun.”

And so it had. When coach Johnny Sweatlock introduced face masks to his football team at Ramsey (N.J.) High, in 1953, he said of his young players, “The boys aren’t sissies, they’re just intelligent.” By the next year, 75% of high school teams provided at least one player on their roster with a face mask and a mouth guard, and 89% of coaches encouraged the wider use of masks.

NFL players were already wearing face masks. In 1955, George Preston Marshall, who owned the team in the nation’s capital, asked league commissioner Bert Bell to ban them. “If a player is required to use a mask,” Marshall said, “he shouldn’t be allowed to play football.” Thirty-two of the 33 Washington players disagreed with their owner, many of them strenuously. Tackle Don Boll, who had broken his nose seven times at Nebraska, said, “If they took my mask away, I’d quit pro football.” Tight end Norb Hecker, who’d had six teeth kicked out while playing for the Rams, and fractured his left cheek bone, said, “[Am I] for a mask? Yes, sir.” Theirs was hard-won wisdom. These players knew the masklessness-as-manliness myth was, almost literally, a barefaced lie.

Marshall, of course, was on the wrong side of history, and not for the only time. Face masks became mandatory in high school football nationally in 1960—the year after Plante revolutionized hockey—and they had instant results. The concussion rate among players sank from three per thousand in 1954 to two per thousand in ’60, according to the American Medical Association. Nine of every 1,000 noses were broken in high school football in ’54, versus two noses per thousand six years later. Dental injuries were reduced from 22 per thousand to 12 per thousand. George Bennett, an orthopedic surgeon at Johns Hopkins, had once declared the steel football face mask “an open invitation to crush someone’s jaw or knock his teeth out.” But in fact, the face mask was making football safer.

And not just football. When college hockey coaches complained in 1980 that masks for skaters invited more high sticking, Paul Vinger, an ophthalmologist and Harvard instructor, said, “Any objective, scientifically based person who’s looked at the data has reached the conclusion that players must wear the mask.”

***

When it came to masks, however, science didn’t always prevail. By the 1960s, the hockey puck had become an airborne pathogen, ever more dangerous to goalies and skaters alike. In that new era of curved sticks, every team suddenly had a sniper with a slapshot, an innovation made popular by Canadiens winger Boom Boom Geoffrion.

And yet, in the summer of ’63, Montreal traded Plante to the Rangers for Worsley, possibly because Plante wore a mask and Worsley did not and Blake still preferred a goalie willing to receive those vulcanized rubber bullets face-to-face, as it were. “I can’t think of any other reason, because [Plante] was great and I was 35,” said Worsley, who was by then an endangered species, and in graver danger with each passing year.

His peers were masking up in self-preservation. Glenn Hall, who once sustained 25 stitches in a single game, and had initially thought Plante a “wimp” for wearing a mask, wore one himself as a member of the Blues in ’68, when he was 37, and shared goaltending duties with he 40-year-old Plante. Like Henry Ford—who was born during the Civil War and died in 1947, when there were more than 30 million cars on American roads—Plante lived to see his creation proliferate.

In a brawl-filled game in 1971, Rangers forward Vic Hadfield ripped the mask off Maple Leafs goalie Bernie Parent and threw it into the stands at Madison Square Garden, where fans formed a bucket brigade to spirit it from security guards and into oblivion. Like Plante before him, Parent—who had only the one mask—refused to continue playing without protection. And so he was replaced by Toronto’s backup goalie, Jacques Plante, who was nearly 42, still playing at the scene of his historic stand. Parent would be back in goal a couple of nights later in a new mask, having paid $150 to its manufacturer: a Montreal company owned by Plante.

Gump Worsley was still not among Plante’s customers. He soldiered on without a mask, incurring horrific injuries, though not all of them facial. His ear was once blackened like restaurant tilapia by a Bobby Hull slapshot. The scar on his right arm was a souvenir of Hull’s skate blade. “The blood flowed like soup,” Gump said of that particular injury, and the dentally ravaged Gumper knew soup—and other entrees that could be sipped, slurped or gummed. In 1960, after losing a tooth and getting seven stitches, Gump doubled down and said he wouldn’t even wear a mask in practice. Jocular, sprightly and lovable, Worsley thought “face cuts and stitches shouldn’t count as injuries in hockey.” And besides, he said, you can always get new teeth. By ’71, when he was 42 and growing wistful—when almost all of the goalies around him had put one on—Gump sighed: “It’s too late to wear a mask. The movie talent scouts have written me off.”

But it’s never too late to do the right thing. And so Worsley had a minor epiphany. False teeth can help a man chew, but a glass eye can’t help him to see. In 1974, as a 45-year-old netminder with the abysmal Minnesota North Stars, Gump wore a mask for the final six games of his 21-year NHL career. “I still had my two eyes,” he reasoned. “I decided to thank God for small favors.”

Between Plante’s wearing a mask in 1959 and Worsley’s wearing one in 1974, the NHL had grown from six to 16 teams, necessitating a transition from train travel to flights. Fearless in net, Worsley was terrified of flying, something people did frequently before our current age of pandemic, when commercial air travel requires a mask that many still resist or resent.

Plante retired while in the Oilers’ training camp in ’75. He was 46 years old, the mask having extended his career even longer than he had thought possible. Plante moved to Switzerland, though he frequently flew back to North America to conduct goaltending clinics. Like the nervous-flyer Worsley, Plante could hear flight attendants on those transatlantic trips insist that he do what he had already done, so many years earlier: Place a mask over his own nose and mouth, before assisting others.