In advance of his new book, the Hall of Fame running back looks back on his controversial college career at SMU, the contentious trade to the Colts, racism at all levels of football, and the fight—and need to continue fighting—for social change.

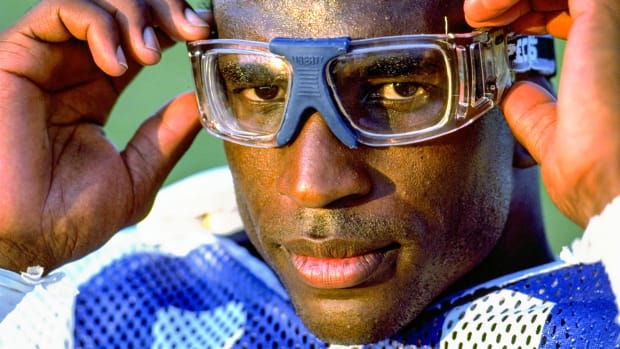

As the years flew by, and Eric Dickerson settled into “retired” life with a similar ease to how he once whirled through NFL defenses, he continued to spin stories. So, so, so many stories. About his childhood in Sealy, Texas. His controversial time at Southern Methodist. Racism he experienced. The NCAA “cartel.” Or, from his NFL career, those 11 glorious seasons from 1983-93 with the Rams and Colts (mostly, along with the Raiders and Falcons cameos). Often, whenever he finished one tale or another, the listener would say the same thing. You should write a book.

For years, Dickerson considered that very prospect. He certainly had enough material, and much of the best stuff had gone unsaid. But it wasn’t until 2020, when he realized that his experience as a Black athlete in America’s most popular sport could inform the chaotic world he currently lives in, helping readers to understand why so much hasn’t changed—and why it needs to—that he decided to move forward. Which is why he called recently, to discuss writing and running, racists and fame and warped perceptions, and his forthcoming memoir, to be released by Haymarket Books.

Why now? Dickerson starts back in Texas, with a town divided along racial lines even in the late 1970s. He says he went to the Black school, until the coaches at the white one found out he could play sports. He had already been adopted back then, by a great, great aunt, and never found out that his biological father had played football until after a teacher saw him star and noticed a resemblance in how they ran.

Looking back, he says, he hates how he was treated. He’s not angry about it, but he knows it wasn’t right. Outsiders, he says, media types and counterparts and enemies, painted him as a villain, a bad guy, an ingrate, a malcontent. He laughs. He didn’t know what half those words meant when “they” affixed those labels on him.

The money SMU players were said to receive? He laughs. That’s in there, too, his side of all these stories that strangers think they know. He calls the perception of piles of cash stacked to the ceiling “bigger than reality.” He thinks he wasn't paid enough. And he says that fans who think their schools are clean, that they aren’t cheating, choose delusion. “The thing is, the NCAA are the biggest pimps of all,” he says. “I call them pimps, because they pimp all these players, they make all this money, and they give out … a whole year’s scholarship and board. That’s almost like a form of slavery. You make this money for us. We’ll board you.”

He’s simmering on the phone now, coming to boil, the memories flooding back. He says it was important that the book feel authentic, that he provide his co-writer, Greg Hanlon, with material that stayed fair to the life he lived, even when it hurt, or cast his actions in a negative light. Sometimes, just talking about these long-ago events felt cathartic, like an ongoing therapy session. “I’m not a bull-s----er,” he says. “You might not like what I say, and the truth is not always popular. But it is, ultimately, the truth.”

Like his time with the Rams, Dickerson says, jumping in timeline from the 1983 draft to the middle of the 1987 season. Fans shouted the n-word at him from the stands, he says. Called him ungrateful. Said he only cared about money—and this, after the ’84 campaign, when he set the NFL single-season rushing record for 2,105 yards. He says he’ll detail why he wanted out of Los Angeles, why he forced a trade (to Indy), why it matters now that a player then demanded to be compensated for his true worth. “I’ll never forget, our general manager, John Shaw—I like John now, but I hated him then—he said that players are horses,” Dickerson says. “You open the gate, and they’ll run.” He says Shaw wanted to send him to “Siberia” and bragged to Dickerson of his plan.

Those same attitudes, Dickerson says, remain pervasive in a league with largely Black players and largely white management and ownership. “I mean, it really is [the same],” he says. “They still treat the players bad. You only have a few Black coaches and Black general managers. It’s sad to see it, and it hasn’t changed.”

The mechanics of the NFL—the media obligations, the coaches who consolidated all the power, the fans who back the billionaires over millionaires, every time—forced Dickerson to hate football, he says. He loved the game, the way the grass smelled, even practice. He despised everything around it. There were times he wanted to quit.

Watching current players address racial injustice, he says, fully warmed up on the phone now, reminds him of his experience in high school. He had a mom, the great aunt who adopted him, who told him he wouldn’t ever be treated fairly. She had been born in 1904, he says, and witnessed the worst of America’s terrible racial history: lynching, hangings, murders, rape, segregation. Not heard. Seen. She told Eric, “I’ve seen white men cut people’s privates out.”

During his high school career, Dickerson says he came to understand, on a much smaller but still very real level, what she was talking about. His coaches always seemed to call quarterback sneaks for their white QB near the goal line. Eric complained. “Son,” she responded, “just do those long runs.” So, he did. From the high school coach he calls racist, the one who led him to quit for part of a season and later apologized for his wrongs; to college glory; all the way to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. “What people don’t realize is what we’re still trying to get is equal; not better, just the same,” he says, voice climbing.

He points toward Anthony Lynn, his friend and the Chargers coach. Keep losing, he says, and Lynn will be fired, despite finding a franchise QB in Justin Hebert, reconfiguring a roster with high turnover in an uncertain year and dealing with a rash of injuries through the season’s first month. “As a Black coach,” Dickerson says, “you start losing and your days are numbered. I mean, it’s just facts.”

Half an hour has flown by like one Dickerson’s long touchdown runs. He says he wants his son, Dallis, to love football as much as he did, but never lose what his father lost. Never have that kind of coach. Never be saddled with that kind of reputation. Never have to clarify his side in, well, a book.

Dickerson sighs after 45 minutes, perhaps realizing all that he has shared. “That’s just some of the stories,” he says. “If you want to know them all, you’re gonna have to …”