As the powers that be consider (again) an expanded postseason, a recently uncovered artifact reminds us this is nothing new.

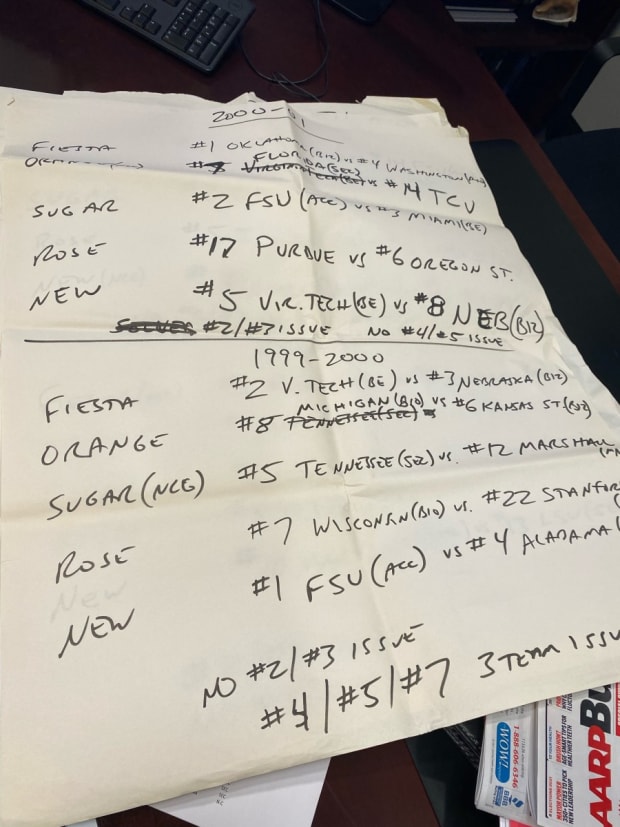

For nearly 14 years, Charles Bloom has kept a secret. On the campus of the University of South Carolina, inside his office, buried within a cabinet, tucked beneath some old newspapers, are handwritten relics of one of his career’s most important—and clandestine—missions. The 13 pages of white easel paper are proof of the secret five-person committee charged by a group of conference commissioners in 2007 with exploring a College Football Playoff.

Bloom, 59, a longtime athletic administrator who is now the Gamecocks’ executive associate AD, sifts through the papers. “Some of this looks like chicken scratch,” he laughs. “Hey, it’s not my handwriting!” Then he comes to a line reading, does a playoff make the rest of the bowls less relative? “Some of the issues brought up today, I look at them and say, ‘We talked about this 15 years ago,’ ” Bloom says.

Douglas DeFelice/USA TODAY Sports

Indeed, as college football launches into the latest effort to revamp its postseason, the people who have led the previous endeavors are quick to remind us of something important: We’ve been here before.

And in every previous case, a playoff proposal ended in rejection.

In 1976, the first instance of serious deliberations, the 17-member NCAA Playoffs Feasibility Study Committee presented two- and four-team proposals. They were never even put to a vote. In ’88, DeLoss Dodds, the former Texas athletic director, chaired a playoff subcommittee that saw a one-game playoff voted down by a 98–13 margin. In ’94, as a member of a 25-member NCAA committee exploring a playoff, John Sandbrook, a former UCLA administrator, authored a 300-page tome arguing for an eight-team playoff. The proposal failed due to an old-fashioned power play. “There was a significant number within the membership that resisted the NCAA having control of the playoff,” recalls Cedric Dempsey, the NCAA executive director from ’94 to 2002.

On those occasions, schools could have granted the NCAA authority to manage a football playoff as it does March Madness. “If they had, I don’t think college athletics would be in the place it is now—a place of disaster,” says Chuck Young, the former UCLA president who chaired the 1994 committee. “I think it’s all coming apart.”

College sports are mired in one of the more volatile eras of their existence. Rulings on name, image and likeness have changed the landscape, and Congress is expected to tackle legislation regarding the rights of college athletes. And the NCAA is rewriting its constitution, with the expectation that conferences will be given more authority.

The contention that college sports would be in better shape if the NCAA had been allowed to oversee a football postseason is probably a stretch. But it definitely says something that there are people in the game who regret not turning a playoff over to what is not exactly the most respected bureaucracy in the world. “Who knows what it would have looked like if the FBS football championship had been under the NCAA umbrella?” asks Mountain West commissioner Craig Thompson. “We [commissioners] work collectively, but realistically we are in our own silos. We do what is best for our leagues. I don’t know as stewards that we do enough for the good of the game.”

Charles Bloom

So FBS football remains the only fully sanctioned sport whose postseason is not managed by the NCAA. For a quarter century, since Young’s failed 1994 playoff study, conference commissioners, specifically from the five richest leagues, have called the shots. Any future expansion of the current system, the College Football Playoff, will not involve ceding power to the NCAA but simply allowing more teams into the mix. The current four-team CFP grants access to 3% of the 130 FBS teams, the smallest postseason of any NCAA sport.

However, growing comes at a cost to a bowl system that has been preserved for decades, for historic and financial reasons. Before college football raked in dollars through TV contracts, the bowls supported the game. The argument—bowls vs. playoffs—has hovered over the sport ever since the first exploration into the postseason, in 1976, when bowl executives, fearing a playoff’s impact on their industry, influenced school officials to stymie a vote. Many coaches were also pro-bowl. USC coach John McKay explained, “We have eight or 10 teams who win their conferences, win bowl games, have great seasons. Ten winners instead of one. Everybody’s happy.”

Indeed, the 1994 proposal was undone largely by the Pac-10 and the Big Ten and their commitment to their year-end showdown at the Granddaddy of Them All. “We didn’t want to give up the Rose Bowl to the NCAA and their efforts to get their arms wrapped around the postseason,” says Jim Delany, then the commissioner of the Big Ten. Tom Hansen, then the commissioner of the Pac-10, described the Rose Bowl as a “dividing point politically.”

So college football ended up with two systems—the Bowl Alliance and Bowl Coalition—in the 1990s designed to force a meeting of the top two teams, so long as they didn’t come from those two conferences. That became an issue in ’97, when No. 2 Arizona State played in the Rose Bowl instead of the Sugar Bowl, the Bowl Alliance championship.

The Bowl Championship Series came along a year later, but as BCS fatigue swept across the U.S. in 2007, a group of commissioners, determined to stage a playoff, formed a commission of conference office administrators: Bloom from the SEC; committee chair Nick Caparelli, with the Big East; Mark Womack, another SEC staff member; Ed Stewart of the Big 12; and the ACC’s Mike Kelly.

They were to examine what then SEC commissioner Mike Slive referred to as a “Plus One” system—in other words, a four-team playoff based on the BCS rankings. Slive and ACC commissioner John Swofford, both proponents, presented a model to their fellow commissioners in April 2008 at a meeting in Florida. The other four power conference commissioners were against expansion, with the Big Ten and Pac-10 again citing their ties to the Rose Bowl. Mike Tranghese, then commissioner of the Big East, voted against it because he wanted a human element involved in selecting the teams. “I took more crap for voting against that than you can imagine,” Tranghese says. “It was represented that I stopped the playoff.”

Four years later, commissioners approved virtually the same model, leading to the current CFP. “We oughta go back and get us some royalty fees,” jokes Stewart.

And now, college football’s power brokers are pondering broadening the CFP but facing familiar questions about bowls, academic calendars and how many teams is too many. Bloom recalls one of the talking points during his secret commission’s monthslong exploration. They called it “the playoff creep.”

“We knew it wouldn’t end up at just four,” Bloom says. “It will go to eight teams, 12, 16.”

He pauses. “Hey, that’s what they’re talking about today, right?”

Click here for a visual timeline of College Football Playoff proposals, dating back to 1976.

More College Football Coverage:

• Notre Dame: The CFP's Unlikely Sympathetic Figure

• Brian Kelly's Abrupt Notre Dame Exit Is Nothing New

• Blockbuster Moves Headline Wildest Week in CFB History