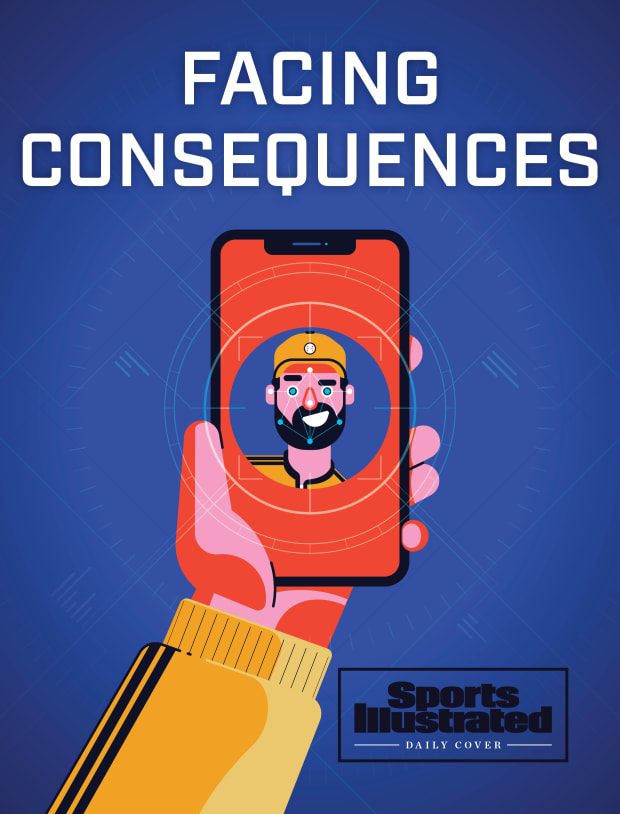

Facial recognition technology—for better or worse—might soon allow franchises to know exactly who is coming to games.

In hindsight, wearing a neon-yellow shirt with funny messages on live TV was a poor way to hide a crime. KP Watershed sees that now. It was like he was livestreaming himself reaching into a cookie jar. But at the time, he wasn’t thinking about consequences. He was just a Yankees fan blinded by the light of a righteous cause, rising up against an enemy of all that the U.S. holds true and dear: Marlins Man.

Yeah, that guy. Marlins Man, the camera-hogging doofus who wears an orange Miami jersey and shows up behind the plate at seemingly every big game baseball game, was going to show up on Derek Jeter Day at Yankee Stadium in 2017, and that was more than Watershed’s pinstriped heart could take. So Watershed put on a bright-yellow shirt and a wristband that looked like the ones they give to Legends section ticket holders, then sneaked down to rep real Yankees fans.

Watershed had developed a belief system as a child, when he would leave his family’s bleacher seats to watch batting practice up close. He hated seeing the stadium’s most expensive seats left empty by people who had so much money that they bought the priciest tickets and didn’t even bother to show up. He enjoyed feeling like a hero of the working class. So he kept going back to the Legends seats. He posted videos on YouTube and spread word of what he was doing on social media. Fans knew him as the neon-shirt guy. He says now that he “naively hoped to raise awareness or outrage,” and he certainly did raise awareness—inside the New York offices.

On Opening Day 2018, the Yankees warned Watershed: Do not sneak down into the Legends seats anymore. But during a rain delay that May, like Superman in a neon shirt, Watershed sneaked down, and two fans asked him to pose for a photo with his Lex Luthor: Marlins Man, who happened to be at that game, too.

The fans turned out to be undercover police officers.

“I was flying too close to the sun,” Watershed says. “The success had gone to my head.”

He figured he would get ejected. Instead, he ended up in Yankee Stadium jail with fellow scofflaws: a woman accused of selling caps without a license and a heavily inebriated gentleman accused of illegally reselling tickets. Watershed was charged with felony forgery. The Yankees wanted him to pay full price for every Legends seat he sneaked into.

He eventually pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct, and had to pay significant legal fees as well as pay restitution to the Yankees. He says his total outlay was five figures. It was not so much to help the $6 billion franchise with its luxury tax bill the next year, but it was a lot of money to Watershed, who manages software for food companies.

But even more painful for Watershed: New York banned him from Yankee Stadium for life.

“Banned for life,” like “zero-tolerance policy,” is a phrase meant for a press release. It’s a conversation-ender. You don’t have to worry about him anymore—we banned him for life. Sometimes the ban is “indefinite,” or a fan is “subject to a lifetime ban”—in both cases, the team is promising the public, essentially, “We’ve got this.”

This season, as the NBA welcomed fans, it also resumed the process of banning them. The Celtics declared a fan to be “subject to a lifetime ban” for throwing a water bottle at Kyrie Irving, just two seasons after placing a two-year ban on a fan for using a racist slur against DeMarcus Cousins. During the regular season, the Jazz banned two fans for life, both for allegedly directing racist terms toward Russell Westbrook.

Then came the playoffs and a flurry of ejections. The Jazz banned three more fans indefinitely for directing verbal abuse at Ja Morant and his parents. (“They should never be allowed back.... this is ridiculous!!!” tweeted Utah star Donovan Mitchell.”) The Knicks banned a fan “indefinitely” for spitting on Hawks guard Trae Young. The 76ers banned a fan “indefinitely” for throwing popcorn at Westbrook.

This raises two questions. One is subjective: What kind of behavior should get a fan banned for life? A racial epithet? Starting a fight? Cussing too loudly? Or in Watershed’s case: Moving down to better seats?

Generally, teams get to decide this themselves. Stadium deals vary by jurisdiction, but it is common for teams to enjoy tremendous freedom in operating their buildings, no matter how much taxpayer money went into building them. That means they can usually decide who can stay and who must go.

This produces some quirky outcomes. The Jazz did not just ban fans from Utah games; they banned them from all events at Vivint Arena, including concerts. And Watershed is still free to watch his beloved Yankees in 29 major league ballparks, just not their home.

After the infamous Malice at the Palace at the end of a 2004 Pistons-Pacers game, Detroit banned fans John Green and Charlie Haddad from all Pistons home games for life for their involvement in the melee. Now the Pistons play at Little Caesars Arena in Detroit. Green and Haddad can attend Red Wings games there, but they remain banned from Pistons home games for life. (Haddad’s response: “I kind of moved on, man. It saved me some money. … Ever since then they’ve been jinxed and they f------ deserve it.”)

The other question is practical: How, exactly, do teams enforce these bans?

“Detailing our specific security measures and procedures jeopardizes their effectiveness which is why our policy is not to share those processes directly,” NBA spokesperson Mike Bass said via email. “That said, there are measures in place to prohibit banned fans from entering arenas and those who attempt to break their bans will be subject to more severe penalties.”

For a long time, those “measures” were limited at best. Fans do not have to show ID upon entering arenas. Teams could run checks on all the credit cards to purchase tickets to see whether any belonged to banned fans, but those fans could easily have a friend buy the tickets. A few years ago, Munich police asked 37 “super recognizer” officers—who supposedly had an exceptional ability to recognize faces—to spot people at Oktoberfest. But most venues did not take that step.

Banning fans for life sounded good, but the penalty was difficult to actually enforce. But soon—and in some places, already—security guards won’t have to know who you are.

“They’ve kicked the fan out; they’ve taken a picture—that fan they know,” says Shaun Moore, CEO of a facial-recognition company called Trueface. “The old way of doing things was, you give that picture to the security staff and say, ‘Don’t let this person back in.’ It’s not really realistic. So the new way of doing it is, if we do have entry-level cameras, we can run that person against everyone that’s coming in. And if there’s a hit, you know then; then there’s a notification to engage with that person.”

The technology is still being adopted, but some arenas like Madison Square Garden have started to use it, and more are expected to do so. Like a lot of modern technology, facial-recognition software can offer unprecedented convenience but also raises privacy concerns.

The potential benefits are vast: Imagine walking into an arena without a ticket because the camera knows who you are. When you go to buy a sandwich and a beer, you don’t need to pull out a credit card—the camera recognizes you and charges your account. Moore calls it “one seamless identity,” but he says implanting it is a few years off. In the meantime, the technology can be used on a smaller scale—like identifying the faces of those who have been told not to show up anymore.

“It’s important here to note that, let’s say that I was not on that banned list and I was walking through; it’s just a regular ticketed customer,” Moore says. “It would not be storing any information on me at all. Trueface would never come to the table with a database of people that the stadium could use.”

It will be up to software companies, building operators, legislators and watchdogs to ensure that facial-recognition does not violate privacy. But widespread use of the technology seems inevitable. It is getting easier to ban fans for life.

When New York banned KP Watershed from Yankee Stadium, they sent him a letter. Like a true die-hard, he had it matted and framed. He continues to cheer for the team.

“I can’t think of anything else I have been banned from, except a fantasy football league for arguing with the commissioner,” Watershed says.

But while he can always join another fantasy football league, he can’t watch Yankees home games anywhere else.

Watershed acknowledges that he gleefully partook in the free food and beverages in the Legends section. He hath sinned! But he still loves the franchise that told him to stay away. He would rather be a Yankee fan in exile than a Mets fan in a box seat.

“I am remorseful,” he says. “I would hope if I am able to show that, they would be open to taking me back. I hope someday I can get un-banned.”

In February, Yankee Stadium became a mass COVID-19 vaccination site. Watershed, who lives in Astoria, Queens, wondered whether he was allowed to go to the stadium for a potential lifesaving shot. But cops had warned him that if he ever went back, he could be charged with aggravated misdemeanor trespassing. Ultimately, Watershed got his shot at a CVS. Entering Yankee Stadium, even for a vaccine, was not worth the risk. He might be recognized by a security guard. Or a camera.