When Willy Suitor soared through the air in a rocket belt at Super Bowl I, it wasn't hard to imagine we would all be flying around someday. Why aren't we?

Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. This year’s WHERE ARE THEY NOW? crop features a Flying Fish and a Captain, jet packs and NFTs, the Commerce Comet and the Say Hey Kid. Come back all week for more.

The National Football League as we now know it was born on Jan. 15, 1967. That, of course, was the date when the scrappy Kansas City Chiefs of the AFL met Vince Lombardi’s NFL powerhouse Green Bay Packers in Super Bowl I. The game, the first big step toward uniting the two rival leagues into what would become the biggest juggernaut in professional sports, drew 61,946 fans to the Los Angeles Coliseum. It was transmitted to another 51 million people at home parked in front of their television sets. It didn’t matter where you watched the game, though, because either way it packed the same thousand-watt thrill of watching history being made in real time. It felt like the future.

Depending on the outer limits of your imagination and your capacity for childlike wonder, there was a second—and arguably more thrilling—glimpse of the future on that clear Southern California afternoon. A future where man’s boundless ambition briefly intersected with the groovy Space Age promise of tomorrow. A future where, for 20 seconds, two men strapped into heavy-metal jetpacks soared above the Coliseum and zipped around in the sky like Buck Rogers.

Super Bowl I would end up being a blowout, as Bart Starr’s Packers wound up trouncing the Chiefs 34–10. The outcome was more or less expected. After all, Green Bay was a 14-point favorite. Anticipating a lopsided contest, the Super Bowl’s organizers knew they needed an insurance policy to keep folks from turning the channel. So they hired a Barnum-esque promoter who’d worked for years at Disneyland named Tommy Walker to put on a spectacular halftime show. Some of Walker’s ideas were pretty cornball: Jazz trumpeter Al Hirt performed; as did the marching bands from the University of Arizona and Grambling State. Ten thousand balloons were released into the air. Big whoop.

But just when things seemed dull enough that you could safely get up and grab a beer from the fridge, two 10-foot-tall footballs were wheeled out to the Coliseum’s 50-yard line. The marching bands took their formations around them. Then the footballs opened up like blossoming tulips and out stepped two men no one had seen or heard of before: William Suitor and Bob Courter. Suitor wore a helmet, white football pants and a dark jersey emblazoned with the letters N-F-L. Courter wore the same outfit, only his shirt was white with A-F-L on it. Strapped to each of their backs was a fiberglass shoulder harness connected to three white Tylenol-shaped tanks containing enough pressurized liquid nitrogen and hydrogen peroxide to act as not-insignificant-sized bombs.

As the marching bands struck up a brassy overture, 300 white pigeons fluttered into the cloudless sky. But the TV cameras didn’t hold on them for long. Because, back at midfield, Suitor and Courter had both just flipped a switch on their packs, releasing plumes of pure white smoke as they gradually lifted off the earth and began soaring into the sky. The two pilots whooshed off in opposite directions toward each 20-yard line, flying at approximately 60 feet. Then they tilted their handlebars, swirled 180 degrees and headed back toward midfield, where they slowly descended to the turf with the ease of a duck settling into a pond. Suitor and Courter then shook hands. The symbolism was hard to miss: the NFL and the AFL were greeting one another and creating a new tomorrow.

After the moment passed, you couldn’t stop thinking about what you’d just seen. Especially if you were a kid. For 20 brief, thrilling seconds, it seemed like science fiction had finally become science fact. Watching these two gravity-defying daredevils, it was impossible not to imagine that one day we would all be flying around like the Jetsons. Each of us a modern-day Icarus blasting into the stratosphere to commute to work, or zipping off to the supermarket to pick up dinner (that is, if our robot butlers were too busy), or maybe just hovering 10,000 feet over Yankee Stadium and watching the World Series from the way upper deck.

It was a heady time in our history, when anything seemed possible. Just six years earlier, during the initial, heated days of the Space Race with the Soviet Union in 1961, John F. Kennedy declared to Congress that the United States would safely send a man to the moon by the end of the decade. Scientists told us that one day we would have colonies on the lunar surface. From there, we would boldly blast off to Mars. Then maybe even Jupiter or Venus. Everything seemed within our reach. Jetpacks just felt like part of that brave-new-world promise. Man would become one with heavens. So what happened? How did this fantasy in which we were promised jetpacks fail to launch?

Fortunately, there’s still one man who can help answer those questions.

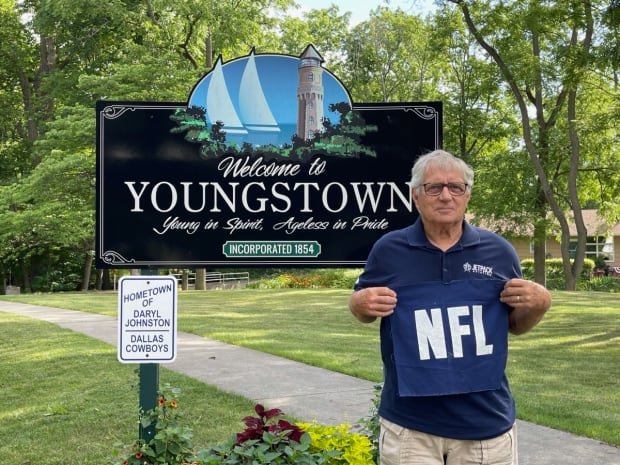

For a guy who used to soar around in the sky at state fairs and sporting events for a living, William Suitor doesn’t much care for attention. He is 76 years old and lives about as far north in New York state as you can without tripping and falling into Canada. These days, he likes to stay near home, mind his own business and spend his waking hours on various woodworking projects. He has seven kids and 17 grandchildren and is proud of each and every one of them. It’s hard to imagine a man more at peace with his life—and more humble about what he accomplished during it. He’s also a tough man to get a hold of, which is intentional. “People can be pests,” Suitor says, referring to the phone calls he still receives from local lifestyle-section reporters and hardcore aviation hounds—and why he tends to not return them.

But here’s the thing. Suitor loves Sports Illustrated, which is why we are talking on this beautifully sunny June morning. But before we go any further, he has two things he wants to get off his chest: First, he insists that you call him Willy (“with a ‘Y’”); second, please stop calling it a “jetpack.” Because the deadly device that Willy flew for most of his career wasn’t a jetpack at all. What he flew at Super Bowl I and during the Opening Ceremonies of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics was technically a “rocket belt.” He patiently explains the difference between the two, going off on thickety digressions about propulsion engineering, chemical compounds, lift, torque and gyroscopic this and that until it’s hard to know whether he’s still speaking English. “I don’t want to go too far down into the weeds about this stuff,” he says too late. Still, while it may sound like semantics to the layperson, it’s important to him. And if it’s important to him, then you can be sure that it’s important. Because whatever you want to call it—jetpack, rocket belt—no one flew it better, or more, than Willy Suitor.

Suitor grew up in the same town that he lives in today—Youngstown, a small village at the mouth of the Niagara River just across Lake Ontario from Toronto. Back in the late ‘50s, one of the biggest local employers was Bell Aircraft, one of the U.S. military’s major contractors during the Cold War. The company was based in Niagara Falls. When Willy was a teenager, one of his neighbors was an eccentric scientist and inventor named Wendell Moore, who worked at Bell as a rocket engineer and helped to design the X-1 that Chuck Yeager piloted to become the first man to break the sound barrier. Willy and the other kids in his neighborhood would gather outside of Moore’s garage, where he would tinker in his off-hours on an experimental plane he was building from scratch. Willy also mowed Moore’s lawn. They never got especially close—Moore didn’t have the sort of warmth that allowed closeness—but Moore would sometimes take his lunch break and sit on the dock by the river where teenage Willy and his pals would water ski.

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

The rocket belt had been Moore’s baby. And after a presentation to the U.S. Army in 1960, Bell got the green light (and the budget) to build a version that might one day be used in combat. The idea was to increase soldiers’ mobility, whisking armed infantrymen from point A to point B in the blink of an eye, forever altering the playing field for how wars had been waged. It would be the ultimate battlefield advantage—a game changer ripped from the pages of a sci-fi comic book.

Moore was the lead engineer on the top-secret project. And as the rocket belt evolved from the blackboard to a realistic prototype, he needed human guinea pigs to fly the thing (Moore had tried it out himself and ended up smashing his kneecap). One day, he bumped into Willy at the supermarket. Willy was 19 and told Moore that he was thinking of dropping out of Erie County Technical Institute, where he was studying to become an architect, and joining the Green Berets. “When I told him about quitting school to join the Army, he said, ‘No, no, no, don’t do that. I think I can get you a job with the rocket belt,’” Suitor recalls. “Unbeknownst to me, he had already gone to my parents and got their permission.”

Suitor remembers taking his physical for the rocket-belt program at Bell in the spring of 1964. It was hardly the thorough, torturous work-over that the Mercury 7 astronauts endured in The Right Stuff. “It was more like cough right, cough left, and if the X-ray of your spine was okay, that’s it. You got the job.” Suitor knew next to nothing about the rocket belt. But he was a quick study, joining a small fraternity of fellow amateur pilots in the program that included Bob Courter, his Super Bowl I flying partner, who passed away in 2013. Willy started off making $3.85 an hour. “We were basically crash-test dummies,” he says, laughing.

Moore’s team at Bell had built five rocket belts in all. When completely fueled up, the rocket belt weighed approximately 125 pounds. But the thing that made the biggest impression on Suitor when he was first strapped in was the noise—130 decibels, similar to a jackhammer or ambulance siren. “It was a high-pitch screeching sound, too, not a roar.”

For his first dozen or so flights, Suitor was attached to terra firma by a safety tether. Then one day, he was informed that they were removing the tether. Was he scared? “No, not really. If anything, I was laughing like hell because that thing was faster than a rat’s ass.” After logging 60 flights, Willy became an official rocket-belt pilot, and Bell sent him on the road nearly every weekend on the exhibition circuit: state fairs, baseball games and aerial shows around the globe from California to South Africa to Australia. In 1967, three years into the gig, Willy also married a woman who seemed to not only understand, but accept, the strange vocation of the man she’d fallen in love with. Fifty-four years later, they are still happily together.

The mid-‘60s to the mid-‘80s were an exhilarating time to be a rocket-belt pilot, Suitor says. The hardware’s blink-and-miss-it 20-second flight duration ultimately made it a bust as a military asset, but in the days after Super Bowl I, jetpack mania took hold of the nation’s collective imagination. “The Super Bowl was definitely the moment when more people around the world had their dreams lit up by this technology,” says Mac Montandon, the author of 2008’s Jetpack Dreams, a history of man’s quest to fly like Flash Gordon and Boba Fett. “And it wasn’t just average citizens—Hollywood really became enamored with it.”

Never ones to let a popular fad go unexploited, both Tinseltown and Madison Avenue were quick to jump on the jetpack craze and give it a show-biz makeover. After all, if kids and their parents dreamed of zooming around weightlessly in the clouds like zero-gravity rocketeers, the big and small screens could give them that spectacle in spades. Before long, Suitor was fielding requests to fly the rocket belt on episodes of Lost in Space, Gilligan’s Island, and later The Fall Guy (where, he proudly boasts, he won an off-camera farting contest with the show’s star, Lee Majors). Suitor was paid handsomely to zip through the sky for a Pabst Blue Ribbon commercial.

Most famously, he doubled for James Bond himself, Sean Connery, for the iconic rocket-belt getaway in 1965’s Thunderball. Overnight, Bell Aviation and its resident lab-coated brainiac, Wendell Moore, had become something like a real-life Q Branch, outfitting 007 with the latest gee-whiz tech (when Connery lands on the ground, he takes off his helmet and says to his comely companion: “No well-dressed man should be without one.”) Connery, who often boasted of doing his own on-screen stunts, had no intention of strapping on the rocket belt himself. So Suitor was tapped to do the show-stopping stunt. Thunderball quickly became the highest-grossing 007 outing of the Connery era. A still of James Bond in a jetpack—the real one this time, not his American double—was placed prominently on the film’s promotional poster.

In 1970, the U.S. Army finally threw in the towel on its funding for the Bell rocket belt program. It was hard to imagine the infantry of the future having much use for a flying apparatus that only worked in 20-second bursts. “It was for foot soldiers to get over obstacles,” Suitor says. “But for the Army the problem was you’ve got control of a jet engine in each hand, so where are you going to hold your weapon? And if you do fire the weapon, what’s the recoil going to do to you?” Adds Montandon, “There was always an element of madness about it. It was always aspirational. But there were a few years there when the Army thought there were real military applications for it. Just imagine, you have soldiers on the front lines able to get from here to there in ways that wouldn’t be possible otherwise.” But even during the free-spending height of the Cold War, the rocket belt was too pie-in-the-sky for the Pentagon. What was once regarded as a potential revolutionary answer for aerial reconnaissance, minefield avoidance and search-and-rescue operations was deemed just another line-item folly that never panned out.

After Bell sold the rights to the project to another company in the private sector, Suitor decided it was time to give up his own jetpack dreams and look for a more earthbound nine-to-five. He got a job with the New York Power Authority, exchanging adrenaline for grounded stability and the promise of a comfortable civil-service pension at the end of the road. But he couldn’t shake the rush of flying the rocket belt. So on weekends and vacations he would still take to the skies at exhibitions around the country. All was going well … until the day Willy had what he calls his “Oh, S--- flight.”

Suitor was 38 in 1982, when he was asked to do a demonstration at the World’s Fair in Knoxville. While flying straight up to land on the roof of a 140-foot-tall building, Willy’s pack stalled. He was running out of fuel fast. Plus, his handlebars were broken. “It was the longest 18 seconds of my life,” he says. “I had some burns on my legs because of the steam coming out. The exit temperature of that steam is 1,000 degrees. My flight suit was torn to shreds. I said to myself, Don’t ever do that again. I’m done. I’m finished.”

But Willy wasn’t finished. And he would do it again. And again. Like a drug, he just couldn’t give it up. Tommy Walker, the same razzle-dazzle ringmaster who had planned the Super Bowl I halftime show, called Suitor and asked if he would fly the rocket belt during the Opening Ceremonies of the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. “It was supposed to be this top-secret thing,” Willy says. “Ronald Reagan was up in the press box and I was hiding behind one of the columns at the top of the Coliseum. But everything that could go wrong did go wrong. The tank was over-pressurized. I was overweight. I hadn’t flown in a couple of years; I wasn’t comfortable. But I had to go through with it. I couldn’t let all of these people down. And it was the Olympics! All I could think about was how proud my kids would be.”

Not that any of 2.5 billion television viewers around the globe would have noticed, but Suitor’s over-pressurized tank did, in fact, make things especially hairy during takeoff. He says it was like he was “holding onto a tiger by the tail.” The rocket belt seemed to have a mind of its own. Yet somehow Suitor managed to control the acceleration enough to make the planned turn and land on the track precisely where he was supposed to. “There he is,” said ABC sports announcer Jim McKay, “Jet Man flying through the stadium, no wires, no tricks, just as you see it!” Suitor was rattled, but soon regained his composure enough to salute the president and turn to the four points of the compass, saluting the audience. The next day, his picture was on the front pages of newspapers on every corner of the planet. It was time to hang up the rocket belt once and for all. And unlike Evel Knievel, he’d managed to stay more or less unscathed and in one piece. Why keep pushing it?

For decades, Willy Suitor did something impossibly cool. He personified our most hopeful fantasies of the future. He lived out the dreams so many of us have but never get to realize. He pushed the limits of tomorrow on deadly wings of hydrogen peroxide and stainless steel. But these days, retired from the New York Power Authority after 32 years, he spends a lot of time in his woodworking shop and being the kind of grandparent who goes to his grandsons’ hockey games. You get the sense that he’s mentally moved on from his rocket belt days. After a couple of hours talking about his extraordinary life—something he made clear more than once that he doesn’t like to do—I begin to get the impression that Willy would rather spend the remainder of the afternoon working on the pergola he’s building over his backyard patio than reliving old glories.

But in 2013, at the age of 69, Suitor would make one last voyage. It wasn’t even for an audience. He would be piloting a new, privately-designed jetpack called the ThunderPack. Willy had helped develop it with an Argentinian entrepreneur named Nino Amarena, who had a dream to sell personal flying devices to the masses. And while the test was a success, the ThunderPack was not.

It was a familiar story. Amarena’s was just one of many vanity tech companies that have tried to get jetpacks off the ground and into the hands of would-be weekend daredevils in recent years. Inventors and engineers continue to build more and more advanced jetpacks even though the same limitations that grounded the rocket belt still dog them: The flying durations are too brief; the cost to produce the devices is prohibitively expensive; the fuel is too combustible; and the faster they go, the deadlier they can be.

Yet, for the same reason that the world was swept up by jetpack mania when Suitor made his breathtaking flight during the Super Bowl I halftime show, the dream refuses to die. In 2007, for instance, a company called Jetpack International, which began by making demonstration-only hydrogen peroxide-fueled rocket packs, announced a jet fuel-propelled model called the T-73 that can theoretically stay aloft for roughly 19 minutes and reach a flying distance of 27 miles at an average of 83 miles per hour. The cost: at least $200,000. Google began dabbling in jetpack technology in 2014, but eventually gave up on the project after realizing they were too inefficient to be practical. A Finnish inventor named Visa Parviainen came up with a wingsuit that had a pair of small turbojet engines attached to the feet.

And then there is the Swiss pilot Yves Rossy, who developed and built a successful kerosene-fueled winged jetpack, which is launched from an airplane and cruises at staggering speeds before the pilot eventually releases a parachute and lands on the ground. Despite successful flights over the English Channel, the Grand Canyon and the Strait of Gibraltar, Rossy’s pack took a serious PR hit recently when one of his flyers, French “Jetman” Vincent Reffet, died in a training accident in Dubai last November.

Undeterred, a handful of other dreamers continue to keep tinkering and experimenting with newer, more cutting-edge packs. There are a small handful of hydro-flight jetpacks on the market that use water to propel the user into the air, almost like a vertical Jet Ski. But these machines, while cool, can’t match the soaring Mandalorian grace of the original Bell rocket belt. Then there’s British inventor Richard Browning, whose company Gravity Industries developed a turbine-powered jet suit that can reach speeds of 85 miles per hour. Browning has been trying to get a competitive jetpack racing league off the ground for a few years—strangely enough, not the only one of its kind. But even stranger was a series of incidents in 2020, when several pilots flying into Los Angeles International Airport reported sightings of a man flying a jetpack at 3,000 feet. Since no current known jetpack can reach those heights, the FAA opened an investigation. Some have speculated that the most likely culprit was a drone with a dummy in a jetpack suit attached to it.

The Pentagon, too, may be getting back into the jetpack business, despite the Army’s failed flirtation with Bell’s rocket belt in the ‘60s. Earlier this year, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) solicited contractors’ ideas for personal air mobility systems. That, of course, could mean gliders and wingsuits. But who’s to say it may not also include another stab at the jetpack?

When asked why our jetpack ambitions have never successfully translated into an affordable, everyday consumer product, Montandon says, “The main reason is: gravity is a b----. It turns out it’s extremely hard to lift a human off the surface of the Earth for more than a few seconds at a time. The physics are beyond daunting. There have been governmental efforts and entrepreneurial efforts, and guys tinkering in garages for decades. And so far no one’s really been able to crack it. Even if we could get up in the air for more than 20 seconds, it would be a traffic nightmare. There would be tons of accidents, injuries and lawsuits.”

The biggest problem, though, is that while a small handful of jetpack obsessives hold onto their Buck Rogers fantasies, their tribe keeps shrinking. The Space Age hasn’t ended, but the sky isn’t the object of fascination it once was. “What was it about seeing those two men in rocket belts flying around for 20 seconds during the Super Bowl that fueled the imagination of people in the ‘60s?” asks Montandon. “What was it about that time when everyone was like, ‘Yeah, we can do anything!’ That sort of optimism doesn’t seem to be with us anymore.”

There was a time, not that long ago really, when a new football league was being born and another vision of tomorrow starring Willy Suitor swept us away. We were promised a future of jetpacks. We were dreamers then. We believed that anything that could be imagined was possible. But these days, our dreams seem different. More tethered to the ground. We seem more interested in looking down at our iPhones than gazing up toward the heavens. It’s hard not to think that something has been lost along the way. Maybe it’s time to look up again.

More Where Are They Now? Stories:

• How Ricky Williams Found Himself in the Planets and the Stars

• The Charmed Season: Revisiting Derek Jeter’s Origin Story

• We Could Sure Use Dick Cavett Right Now