Ahead of a new season, the author of Fever Pitch, the celebrated memoir of football fanhood, considers the fraying relationship between supporter and shareholder.

In 1999, Manchester City, now the richest team in England and the reigning Premier League champion, was playing a future-defining game at Wembley Stadium. As the match approached injury time, Man City was two goals down, but there were five additional minutes to be played. City scored in the 90th and 95th minutes to take the game to extra time and eventually a penalty shootout, which it won.

The game was against little Gillingham, and it was future-defining because it was a playoff game, and it got City out of the third tier of English football. Thirteen years later, and after massive investment, it became the best team in the country. It is not impossible to imagine that if Gillingham’s keeper had pushed Paul Dickov’s 95th-minute equalizer around the post, another team might have been the beneficiary of Sheikh Mansour’s largesse. Sunderland, maybe. Or Birmingham. Or Gillingham.

Leon Neal/Getty Images

There are good reasons to be infuriated by the involvement of every single one of the clubs in the spring Super League fiasco, in which a self-appointed elite group from three countries tried to cut risk and excellence out of the equation and play one another forever, to maximize the profits of the brands created mostly by the players of the past. Of the English “Big Six” that announced their participation—Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United and Tottenham Hotspur—the two from North London, Spurs and Arsenal, neatly and satirically finished seventh and eighth last season. (My team, Arsenal, announced its membership shortly after scrambling to a draw against Fulham, which was relegated not long afterward.) Manchester United, the biggest club in the country, hasn’t won a title for eight years. But for Man City to announce that it was raising the drawbridge was particularly galling. It was nobody’s idea of an elite superpower even 15 years ago. If anyone knows that the fortunes of even the most hapless-looking team can change unexpectedly, it’s Man City.

It is hard to understand what the Super League founders thought was going to happen following their unilateral declaration of independence. It seemed almost calculated to enrage, so one would have expected the protests that ensued to have been anticipated, priced in and fronted out. Instead, the Super League collapsed, like the kind of school bully who has never been punched back before, bursts into tears and runs home to his mum when it happens. But the abandonment of the scheme hardly defused the anger. Manchester United fans invaded Old Trafford and caused the postponement of a game against Liverpool 10 days after the club had withdrawn. As a new season begins, it looks as though the resentment and distrust is here to stay.

Oli Scarff/AFP/Getty Images

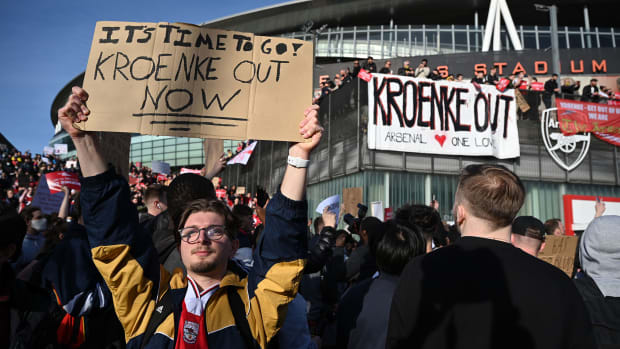

I saw Arsenal play just once last season, due to the pandemic, and it was the last game. I was sitting behind a group of fans who waved their Kroenke Out placards—Arsenal’s American billionaire owner, Stan Kroenke, who also owns the NFL’s Rams and several other U.S.-based teams, is not popular—whenever the cameras went near them, weeks after the Super League scheme had ended in embarrassment and chaos. My teenage sons, both season-ticket holders and obsessives, were disgusted to the extent that there was a family conversation about which London club we would now watch. Brentford? QPR? Orient? The Premier League is the best in the world, unbeatable now in terms of star power and excitement, but the whole family was prepared to turn our backs on it, and on a lifetime of Arsenal fandom, if the Super League went ahead.

This kind of implacable, structural disgust is something relatively new in English football. Every now and again, when it was clear that mismanagement or asset-stripping was taking place, a chairperson or a board of directors would be subject to abuse from fans, but for the most part, this side of the game was uninteresting to us. So how has supporter anger crested over time, fundamentally altering the dynamics of fandom to the point of revolt?

Leon Neal/Getty Images

I started watching Arsenal in 1968, when the chairman was an Old Etonian called Sir Denis Hill-Wood. Sir Denis had inherited the position from his father, an Old Etonian called Sir Samuel Hill-Wood; he passed it on to his son, an Old Etonian called Peter Hill-Wood. Eton is the exclusive boarding school that has wreaked so much havoc on British public life. David Cameron and Boris Johnson went there, as well as 18 other prime ministers.

I can remember a Hill-Wood getting it in the neck only once, in March ’86, when Arsenal made an approach to a new coach behind the back of the incumbent, who resigned. The crowd’s ire was quite precisely targeted. The board had messed up; the board deserved abuse. It had behaved sneakily, without the class that was, at the time, the club’s unique selling point. Yet in ’86, Arsenal hadn’t won a championship for 15 years. Liam Brady, probably the greatest homegrown talent the club has ever produced, had left a few seasons before, for Italy, where he won championship medals with Juventus. He had refused to sign a new contract in part because he felt the club was drifting, refusing to invest in the talent that would turn Arsenal into a title contender. And yet somehow the fans were phlegmatic about this. We supported a team that had won just one FA Cup since ’71, and that was the way things were. The players got booed off sometimes, yes, but that was because we felt they had played badly, rather than because everything was rotten in the state of Arsenal.

A couple of things were different back then. The first is that there was a more level playing field. Recently, I renewed our season tickets—a little bit cheaper, now that there is no European football to watch at the Emirates. We know that what we are paying to watch is a battle to finish in the top six of the Premier League. No Arsenal fan thinks that their club will actually win the Premiership. No Spurs fan believes that, either. If you had to bet on the top two, you’d put your money on Manchester City and Chelsea. In my teens and 20s, Liverpool was a perennial champion, including one stretch of seven titles in nine seasons between the mid-1970s and the mid-’80s, but it was hard to resent the club because it never seemed to buy anyone that nobody else could afford. Liverpool signed Ian Rush, its all-time leading goal scorer, from Chester City, and Alan Hansen, its brilliant central defender, from Partick Thistle in Scotland. Arsenal could have done that, or Aston Villa, or Ipswich Town, the two teams that fought for the league in ’81. A couple of brilliant transfers and some luck, and your team, too, could be up there. Nobody had a squad, really—just a few different substitutes. Nobody needed one. Looking back, one suspects that injuries were dealt with the old-fashioned way, with ignorance and injections. Hardly anyone got a suspension, because hardly anyone got a red card. (Paul Davis of Arsenal got a nine-game ban in ’88, but that was for breaking an opponent’s jaw with a left hook.)

It wasn’t ever a stretch to believe that next year could be your year. After all, Arsenal’s first double—titles in both the league and FA Cup competitions—in 1971, came from nowhere, more or less. It had been 18 years since the previous championship, since even a realistic challenge. And the legacy of that title-winning season vanished almost immediately: It was 18 years until the next one. Even failure seemed to prove that success could come at any time. The ’89 title was won by a couple of defenders bought from Stoke, a center forward signed from Leicester and a bunch of youth-team players. Arsenal’s last league championship was in 2004, with Thierry Henry, Patrick Vieira and Dennis Bergkamp, and, temporarily, the club was a world power, for the first time in my life.

Then came the new stadium, and new ownership—and new owners with near-bottomless pockets at Chelsea and Man City—and a long, steady decline. This course, the road to mediocrity, may one day be corrected, but my sons know they will have to watch a team that cannot compete for a few years yet. My boys are luckier than many fans. They have seen four cup final wins, three of them from inside Wembley, in the last few years. If they were fans of Tottenham—and I bring this up more in sorrow than in a spirit of derision, of course—they would not have been old enough to celebrate any kind of trophy win.

And the other difference was that fans paid very little for entry. There’s no point in giving you the ticket prices, not least because there were no tickets for the majority of fans. You paid at the turnstile and stood on the terrace steps to watch. When I started going to football games without a parent, in the early 1970s, the admission price was exactly the same as the tube journey that took me to the stadium, and our public transport was cheap. It wasn’t so different in the ’80s. And because football was much cheaper than just about any other form of entertainment, fans didn’t think they were owed anything, not financially, at least. These days, when you pay upward of a thousand pounds for a season ticket, you expect certain things: a decent view, an accessible toilet ... and a good team. If you don’t have a good team, then it’s the fault of the people who control the purse strings.

PA Images/Sipa USA

The Hill-Woods were a long way from the fans who stood on the North Bank, in all senses. They sat way up there in the directors’ box, and they had very different life experiences, education and incomes. And yet nothing much was their fault. The Arsenal shareholders received no dividends on their shares, because that wasn’t seen as the done thing. They were paternalistic fans, with the best interests of the club at heart. That’s how we saw it, and that may well have been the case. If we didn’t feel the need for part-ownership of the club, it was because we felt we co-owned it anyway. I was part of a generation that was sold football the way a drug dealer sells heroin: cheap, at first, before jacking up the price. I was hooked, so I pay, and I am lucky enough to be able to pay for my sons, too. Many of their friends, however, go rarely, if at all. Future generations of addicts are not being created. Indeed, they are increasingly being excluded from TV broadcasting. At the moment, you need to find the money for three different cable subscriptions if you want to watch your team play every game.

There was something about the old paternalistic arrangement that worked. Or rather, there was something about the old arrangement that prevented bile and blame. The old breed of chairpeople were usually local worthies who saw a football club as a feather in their caps, a reward for successful if unglamorous careers—and, crucially, had emotional and local links with the teams. Louis Edwards, who took over at Manchester United in the 1960s, was born in Salford, not far from Old Trafford, and ran a meat-processing company. Jack Walker, the man who bought Blackburn a championship in ’95, was an industrialist and boyhood Blackburn fan. Jack Heyward, the owner of Wolves and another boyhood fan, spent his own money on redeveloping the old stadium. None of them were running their clubs as businesses, and were therefore forgiven for their sins. The old days weren’t better, by the way. The stadiums were dangerous. The pitches were awful. The football was numbingly slow and basic. But it didn’t appear as though anyone was being ripped off.

Sipa USA (3)

Now, according to a group of fans, everything is the fault of Kroenke or the Glazers, the American owners of Manchester United. And when Man United and Arsenal announced that they were two of the English teams joining a proposed Super League, a lot of previously unfocused unease and dissatisfaction found a perfect target. In the minds of the fans, it was the American owners—Liverpool, another of the breakaway teams, is owned by U.S.-based Fenway Sports Group—who didn’t understand the culture and traditions of the English game. After all, in the U.S. teams disappear in the middle of the night—that’s how much owners respect their franchises’ histories and supporters. And something like that was what was going to happen to us, if this thing were allowed to go ahead. The English clubs would start playing each other in Singapore, or Tokyo, or L.A. But mainly the rage was about the disrespect shown to the integrity of the English football pyramid system. If the same teams appear in the Super League every year, then what, precisely, is the point of the Premier League? What is the point of coming out on top of it? Why would these self-styled giants bother to play their stars for a game against Everton or Aston Villa?

Such bad, bad, cynical, money-grabbing Americans! And yet closer analysis of Kroenke’s evil reveals some perplexing details. Since he took full control of the club in 2018, a succession of Arsenal managers have asked for money to spend, and they were given it. They spent it on, among others, center back Sokratis, who cost £17.5 million (or $22.9 million), and whose contract was canceled in January; goalkeeper Bernd Leno, who cost £22 million and is thought to be falling out of favor after a patchy season; midfielder Lucas Torreira, who cost £26 million and seems likely to depart after spending last season on loan; central defender William Saliba, who cost £27 million two years ago and has yet to play a single minute for the club in a competitive match, such is the apparent distrust of his abilities; winger Nicolas Pépé, who cost £72 million and who might yet turn out to be a good, if shockingly overpriced, signing; midfielder Thomas Partey, who cost £45 million and spent much of his first season on the treatment table, recovering occasionally for a wayward performance here and there; and former Chelsea midfielder Willian, who came on a free transfer but was given a three-year deal worth £200,000 a week, and has looked both lost and unhappy since he joined.

PA Images/Sipa USA

Meanwhile, up in Manchester, the Glazers have spent £130 million on two defenders—one of whom, Harry Maguire, is no Virgil van Dijk, but was pricier than the Liverpool center back anyway—and £35 million on Donny van de Beek, bought last summer and now apparently for sale after hardly playing. If the Kroenkes and Glazers feel somewhat exasperated by the constant accusations that they don’t invest in their clubs, one could perhaps forgive them.

If it is possible to judge these things from the outside, then it looks to me as though the happiest fans of the self-styled Big Six are those who support Liverpool, Manchester City and Chelsea, and cynics might wonder whether the fact that these three teams have among them won two Champions Leagues and a handful of Premier League trophies and domestic cups over the last few years is what makes the difference. City and Chelsea are run by owners who seem quite happy to keep pouring money straight onto the pitch, regardless of whether it makes any business sense. This quirk seems so successful, and to delight the faithful so much, that now everyone wants that kind of owner. But Liverpool’s ownership has a hedge-fund mentality, which traditionally is not interested in adding to the sum total of happiness. It appointed a great manager, however, bought great players and produced a team that played fast, winning football. Maybe Arsenal could have done that, if it hadn’t squandered nearly £200 million on the wrong players. Maybe Spurs could have done that, if they hadn’t sacked a coach that their players loved and replaced him with a coach they clearly disliked so much that some of the best ones have lost all faith in the club and want to leave. Maybe Man United could have done that, if it hadn’t spent over £160 million on Maguire, van de Beek and the inconsistent midfielder Fred. Maybe the chief issue at the core of fan unrest goes beyond ownership finances and sporting decisions and hits on something that is deeper, yet, on the surface, also so simple.

PA Images/Sipa USA

In 2010, Leicester City was sold to a Thai consortium. Leicester was in the second division then. It was promoted back to the Premier League in 2014, but after 29 matches of the 38-game league season, it was rock bottom, with 19 points. It survived, miraculously, after a stupendous and unlikely run of wins. When your club is fighting relegation, then survival is as ecstasy-inducing as a trophy. If any Leicester fan had said, in the summer of 2015, that the following season might be Leicester’s season, you would immediately have tried to sell them the T-shirt on your back for millions of pounds. The following season, Leicester won the Premier League. It’s still hard to believe, five years later, that it actually happened, that a team so perilously close to relegation could transform itself so utterly that it could beat Liverpool and United and City and the rest, consistently. The three shining lights on the team, Jamie Vardy, Riyad Mahrez and N’Golo Kanté, were bought for a combined total of £8 million; the latter two were later sold for roughly £90 million. I don’t think I have ever seen a happier group of players and fans than Leicester’s at the end of that season.

In 2021, Leicester, with another generation of cheap (relatively speaking) and spectacular talent, beat Chelsea in the FA Cup final and finished fifth in the table, only after a disappointing late-season collapse. It is not a traditional Big Six team, of course. It just wins a lot, beats the superpowers regularly and plays with heart and skill. I have no idea what Asian Football Investments wants from Leicester City, whether it is running the club as a business, whether its motives are pure. I do know that it had no links to the community before buying the club. I also know that Leicester fans don’t give two hoots. They are stakeholders, because they are proud of their team and the way the club has been run, and that’s enough. In the end, I think it would be enough for all of us. It would certainly be enough for my kids.

Nick Hornby is a bestselling, award-winning author whose latest book, Just Like You, will be published in paperback on September 28.

More Soccer Coverage:

• Wilson: What Messi Signing With PSG Means in the Grand Scheme

• Creditor: Projecting the USMNT's First World Cup Qualifying Squad

• Straus: Qatar Makes Itself at Home in Concacaf

• Wilson: Grealish Transfer is a Gamble Man City Can Afford to Take