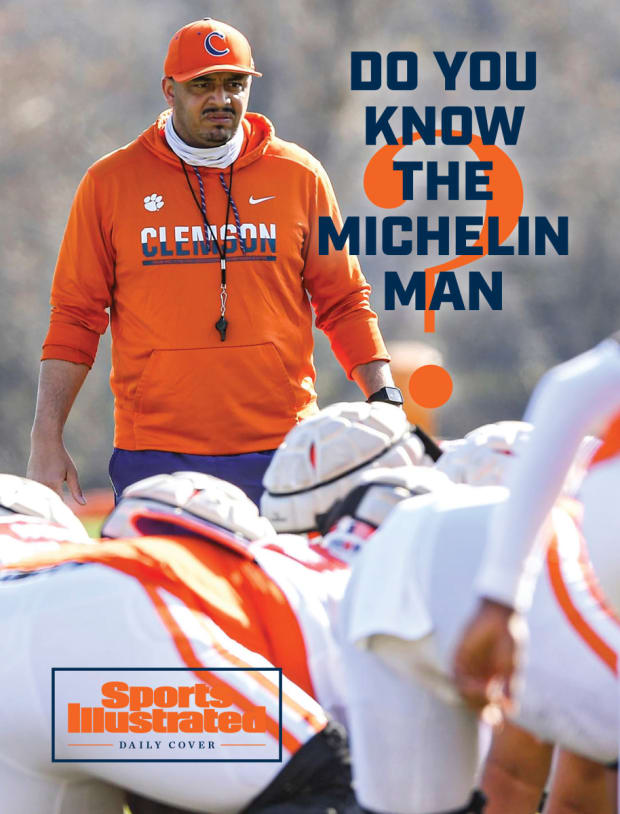

He was a top engineer at a rubber plant. Now he coaches a championship-winning college offense.

Before anyone else, Kim Neal knew Tony Elliott was destined to be a football coach.

For almost two years, Elliott worked under Neal as an industrial engineer at a Michelin tire plant in Anderson, S.C., the largest such plant in the entire world. There, they examined, refined and manufactured pre-processed rubber, distributing it to other plant sites for the creation of actual tires.

Elliott was so good at this job that within a year Neal promoted him to oversee the entire plant. In his mid-20s, with just a few months of real-world experience, Elliott lorded over veteran engineers, pooling together workers during training sessions and meetings in a way that Neal had never seen. He maximized their talents, cross-trained them in multiple roles and developed a camaraderie second to none.

Ken Ruinard/USA TODAY Network

The plant became Michelin’s most productive.

“We outpaced all of the plants just because of Tony,” Neal says. “One day, I said to him, ‘Tony, with Michelin, you’ll go to the top and be a vice president. But will you be happy?’ ”

Deep down, Neal knew the answer. And a few months later, there stood Elliott in the doorway of his boss’s office, holding a letter of resignation.

Fifteen years later, Elliott starts his seventh year as Clemson’s offensive coordinator and play-caller, directing one of college football’s consistently electric offenses while confounding much of the industry by showing little interest in moving up the coaching ladder. After all, he’s a $2 million-a-year coordinator at a championship-winning powerhouse who, as of last fall, did not even have an agent.

Elliott guided Trevor Lawrence, Travis Etienne & Co. through a bizarre but high-flying 2020 season that produced an incredible statistic: In back-to-back years, Clemson’s offense finished in the top four nationally in scoring.

Extending that streak to three will be a monumental task. Gone are Lawrence, Etienne and four more offensive starters, and there’s no time for any tune-ups. The No. 3 Tigers open the season with Week 1’s biggest showdown—a clash with No. 5 Georgia in Charlotte.

One of the most essential and persistent figures within Clemson’s juggernaut of a program, Elliott says he might not be here if it weren’t for his old boss at Michelin.

“He saw I was struggling internally,” Elliott says. “He saw there was something missing.”

Kim Neal

Those close to him describe Elliott as a humble, salt-of-the-Earth type of guy whose rough upbringing has made for one of the greatest underdog stories in college football.

Most know Elliott’s story by now. Son of a father who spent years in prison, Elliott, his mother and little sister were at one point homeless, living on the streets of Los Angeles. Once they finally found safe harbor, the matriarch of the family died in a car accident that Elliott, his sister, stepfather and stepbrother survived. He was the first to tend to his mom, thrown from their vehicle and lying in a puddle of her own blood.

From there, Elliott turned to sports, paid his own way to Clemson as a walk-on receiver and eventually ascended to team captain as a senior, the apple of the eyes of both his position coach (Dabo Swinney) and head coach (Tommy Bowden).

That’s where Neal enters—the storyteller in an untold chapter of Elliott’s inspiring tale.

Neal, 65 and now retired, recalls pouring over résumés for an open industrial engineering job back in 2004. He stopped at one résumé, the man’s GPA catching his attention. Industrial engineering is one of the most difficult majors at any university. A GPA above a 3.0 is good. A GPA above a 3.5 is great.

Antonio Elliott, the name listed at the top of the résumé, had a GPA of 3.55.

It wasn’t until he moved toward the activities section at the bottom did Neal realize this applicant was, in fact, the Tony Elliott, a receiver for Neal’s favorite team and alma mater, Clemson. He brought him in for an interview and hired him.

“He blew me and the rest of my team away,” Neal remembers.

At the plant, Elliott started each day by slipping into his company-issued denim coveralls and working on various projects, most notably optimizing the weight of fabricated rubber as a cost-saving venture.

Sounds fun, right?

“When I’d go home at night, all I’d do is go out to eat and wish it was always Saturday so I didn’t have to go back to work,” Elliott says. “It’s not because I didn’t enjoy my job. I just didn’t feel like I was fulfilling a purpose.”

Though not his passion, Elliott excelled at the gig. Within a year, Neal promoted him to a management-type role where his main duties were developing teams within the plant to better utilize labor and streamline production. He was such a master at building teams that Neal, knowing of his pupil’s true passion, suggested Elliott work as a volunteer coach for a struggling local high school football team, the Easley Green Wave.

In a part-time role, Elliott had such a strong presence that the head coach all but relinquished control to him, says Neal, whose son played for Easley.

“I knew then,” Neal says. “You could see the gleam in his eye. This is what he wanted to do.”

The truth is, Elliott had an affinity for coaching from the start. In fact, Bowden remembers his walk-on receiver entering his office to discuss a career in the profession. Bowden, now retired and living in Destin, Fla., outlined the good and bad of the industry.

“I talked him right into going into engineering,” Bowden laughs.

As a player, Elliott was tough, humble, hard-working and somewhat quiet. His path reminded Bowden of his own and of Swinney’s. All three were walk-on receivers who worked their way into a role on the team—Bowden at Florida State for his dad, Bobby; Swinney at Alabama for Tommy Bowden, then a Tide assistant; and Elliott at Clemson for Swinney.

There’s just something about walk-on receivers.

“You have a chip on your shoulder. It’s a ‘I’ll prove something to you,’ ” Bowden says. “My own father didn’t offer me a scholarship and signed a guy on my own team who I had to beat out.”

Following his part-time stint with the Eagles, Elliott took about three months to think on his decision: become a coach or remain an industrial engineer.

“When I got out of school, that’s what I believed I wanted to do—be an engineer,” Elliott recalls. “Get my white house with a picket fence and live the American dream. But [Kim] saw that I was struggling.”

Ken Ruinard/The Greenville News/USA Today Network

In South Carolina, long before Clemson became the powerhouse it is today, years before Steve Spurrier showed up to make the Gamecocks competitive, there was one name in the state that carried weight: Michelin. Its North American enterprise was headquartered in Greenville.

So when South Carolina State coach Buddy Pough got a call in 2006 suggesting he hire a Michelin engineer as his receivers coach, he naturally balked.

What in the world does a well-paid math whiz at Michelin want with football?

“Why should I do this?” he asked Brad Scott, a Clemson assistant and the man who originally suggested Elliott.

“Because I think he’ll be a good coach,” Scott replied.

And so went Elliott, out of the tire business and to a 3,000-student historically black college in rural South Carolina.

Orangeburg, S.C., is no metropolis. In fact, Cleve McCoy didn’t exactly know what coaches did when not coaching football. Maybe that’s why he always saw them in the football offices, which were converted dormitories.

The nightlife in the city was akin to the financial resources at the university—they were both somewhat nonexistent, especially 13 years ago, when McCoy quarterbacked the Bulldogs.

But for a few months, in the offseason following the 2005 season, this place was home to two 20-something assistant coaches whose names are oh-so recognizable today: Tony Elliott and Billy Napier.

McCoy, who now trains quarterbacks in Minnesota, often finds himself shouting at the television when his former coaches grace the screen.

“I look at them on TV and I tell my quarterbacks that I trained and learned from some of the best coaches in the nation,” he says.

Scott, now with his son Jeff at South Florida, orchestrated the move to get Napier, a Clemson graduate assistant, to SC State as well. In many ways, Elliott and Napier arrived as a package, Pough says, though Napier got there a year before.

It gave them a chance to develop as coaches and gave South Carolina State cheap labor, laughs Pough, who in his 18 years as head coach has returned the Bulldogs to the MEAC powerhouse they were in the 1970s and 80s.

“You knew both guys were stars early in their careers here,” he says. “I couldn’t afford to keep them. It was one of those kinds of deals—big fish in a little pond.”

Oddly enough, Napier and Elliott have become two of the most sought-after coaches for elite head coaching jobs, both of them bucking what was once a somewhat normal trend—coaches, no matter the circumstances, leaping to their next big thing.

In his third year as head coach at Louisiana, Napier has won 28 games, three division titles and a conference championship. In six years as Clemson’s offensive coordinator or co-offensive coordinator, Elliott has captained one of the country’s best units.

Watch the Clemson Tigers online all season long with fuboTV: Start with a 7-day free trial!

Patient and prudent—you might call them picky—Napier and Elliott have either turned down interest or declined an offer from a dozen suitors over the last couple years.

What gives?

“They’re different dudes,” says Bobby Lamb, head coach at Anderson University, a Division II school just a few miles from Clemson.

Lamb is another link between the two men. He coached Napier at Furman from 1999 to 2002 and gave Elliott his second coaching job in 2008.

“I know he’s been up for some jobs and behind the scenes he’s turned some down. I don’t see him leaving for a while,” Lamb says. “He could coach 10 years as the OC at Clemson and then walk away and retire. You don’t get far in negotiations with him, and he always says, ‘I got to concentrate on getting Clemson to the national championship game.’ ”

Lamb still regularly communicates with Elliott. Just as a person off the field, he ranks Elliott No. 1 among the dozens of assistants he’s had in a 16-year head coaching career at Furman and then Mercer.

He’s happy for a kid who came from virtually nothing, turning a crease of an opportunity into a multimillion-dollar gig.

“God’s honest truth: Tony Elliott was making $36,000 in 2010 [at Furman],” Lamb laughs. “What a great country we live in.”

Ken Ruinard/The Anderson Independent Mail/USA Today Network

Years later, even as a football coach, Elliott uses his engineering background in mathematical schematics as it relates to the game.

He describes himself as somewhat of a math nerd. Numbers always came easy to him.

Neal remembers his former subordinate’s intellect as superior. He was mature well beyond his years, the perfect fit to become one of the company’s youngest vice presidents.

And then football happened.

Neal says Elliott took a five-figure pay cut in leaving Michelin, but “he’s well made up for it by now,” Neal laughs.

Elliott describes Neal as the guy who encouraged him to actually leave engineering. He recognized the passion his pupil had for another career. Instead of persuading him to remain in the industry, Neal fostered Elliott’s path in coaching, even if it meant losing his best worker.

“He inspired me to chase my dream,” Elliott says.

The two still stay in touch, texting every few weeks and even holding the occasional phone call. Every now and then, one of Neal’s former workers will ask about Elliott—the guy who once rallied a rubber-manufacturing plant to its best production ever.

“A few years after he left, I got a call from Danny Pearman [then and now an assistant on the Clemson staff]. We used to be neighbors,” Neal says. “I knew what he was calling about and he knew what I was going to say. He says, ‘We’re looking at hiring Tony for the open running backs coach job.’ ”

You’re a fool, he told Pearman, if you don’t hire Antonio Elliott.

Read more of SI's Daily Cover stories

Sports Illustrated may receive compensation for some links to products and services on this website.