When Ohio State takes on Alabama in Miami, Trey Sermon's family will be returning close to home. It's a place with both happy and horrific memories.

MIAMI — About 200 miles from here, almost due north on Interstate 95, about 10 miles east of Orlando, a tall chain-link fence surrounds a nondescript array of buildings.

They are beige with brown roofs, and in between them are courtyards of lush grass. There is a small paved parking lot for visitors and a brick sign that politely explains what this place is.

“Florida Department of Corrections,” it says. “Central Florida Reception Center.”

In more brusque language, this is a prison. It is occupied by some 1,600 people, all men. As is the case in most correctional facilities, people here are identified by a six-digit number. Their names are, for the most part, secondary.

At this particular facility, there is a 57-year-old man who has been given the number 261728. He’s in his 27th year of a life sentence behind bars for some of the most heinous crimes imaginable.

On Monday night, when Ohio State kicks off the national championship game against Alabama, its standout running back, Trey Sermon, will be returning home, or at least very close to it (he was born in the Tampa area).

There are good memories here. And there are bad memories here. Some of them aren’t even memories. Some of them are stories, horrific tales that he knows only because his mother told him.

Sermon does not know the man, prisoner No. 261728, who resides a three-hour’s drive from Hard Rock Stadium. But he knows of him.

Well before Sermon was even born, more than a half-century ago now, prisoner No. 261728 beat Sermon’s pregnant mother and later murdered her 2-year-old son.

***

Natoshia Mitchell lost two children before she turned 30.

Both of her brothers are dead, one of whom was shot seven times. Her mother died in an untimely fashion and then, two weeks later, her father was killed in a car accident. She had an abusive childhood and then she entered into an abusive relationship with the man who eventually killed her baby boy. Years later, her second-born, a daughter, died at birth.

Mitchell talks openly about her past. She’s even detailed it in a 136-page book meant to inspire those who have experienced similar grievances. The book, When My Soul Cried, details much of her first life, the one that saw so much hatred, grief and sorrow; the one she left, physically and emotionally, years ago to create her new reality.

In her second life, Mitchell resides not in Florida but in Georgia. She has two grown children, each of whom she is incredibly proud, and a bubbly nine-year-old granddaughter. She is a few months from finishing her doctorate in psychology after already holding bachelor’s and master’s degrees. She has plans of opening her own clinic with her daughter, Oneisha.

Lastly, the twinkle of her eye, her 21-year-old son Trey, has burst onto the college football scene with a dazzling string of rushing performances as his Buckeyes (7–0) barrel toward the title bout here against the Crimson Tide (12–0).

Things are splendid.

Life is good.

“When I came [to Ohio State], my goal was to do whatever I can to help this team out and play for a national championship,” Sermon says. “It's all happened, and it does kind of seem like a dream.”

***

It wasn’t always so dreamy. Sermon transferred this past offseason from Oklahoma seeking a more significant role, but he found himself in a place similar to the one he left in Oklahoma—down the depth chart. Adjusting to a new rushing scheme and behind tailback Master Teague, Sermon grew frustrated.

But then, before a game against Michigan State on Dec. 5, came a heart-to-heart with his mentor, Tuna Burhanan, a longtime strength and conditioning coach in the Atlanta area. Burhanan and Sermon discussed the “sense of urgency” that the running back should have as his college career was winding down.

“He felt like he was at Oklahoma again and that no one knew his worth,” Burhanan says. “I told Trey, I said … they’re just not giving you an opportunity, but don’t let that hinder you. It makes you run slow and run like a robot and you’ve got to get that out of you.

“He just stopped thinking, changed his attitude at practice and his position on the team and in life in general,” Burhanan says. “Now you see the true Trey Sermon.”

Starting with the game against the Spartans, Sermon has run for 636 yards in three consecutive games with four touchdowns and a staggering yard-per-carry number: 9.08. Ohio State coach Ryan Day calls Sermon “the best part” of the Buckeyes’ storybook tale of 2020—from not playing football this season, to playing football, to having three games canceled, to upsetting Clemson with a rout last week.

“It's really remarkable what he's done,” Day says.

In the Big Ten championship game, an outing in which Ohio State’s passing attack struggled, Sermon carved through a Northwestern defense known for being fundamentally sound. He had 331 yards against the Wildcats. In the College Football Playoff semifinal against Clemson, Sermon gashed another usually salty unit, going for 193 yards and ripping off runs of 34 and 30 and, at times, carrying the load while his quarterback and childhood friend, Justin Fields, nursed rib injuries.

Sermon went viral for more than his running ability. After a touchdown of his was reversed because his knee touched the ground, an ESPN sky camera caught his smirking directly toward the lens in a sly and hilarious way. Ohio State’s official Twitter account even used the picture of the smirking Sermon in a not-so-subtle shot at rival Michigan.

His mom has seen that look before.

“Trey is a character,” Mitchell says. “That’s one of those looks when we’re at home and we’re teasing him and he’ll look at me like, ‘Are you serious?’

“He told me, ‘I knew the camera was looking and I was being silly!’”

While everyone tries to figure out who this guy is and where he came from, Burhanan chuckles. He’s known all along. Sermon just needed more opportunities, more carries, to find a groove. Teague’s injury in the Big Ten title game opened that door.

But it’s not like Sermon is completely new to the college football scene. One of the most highly ranked running backs out of high school, he was named the Big 12’s Offensive Freshman of the Year in 2017 in Norman. He eventually slipped behind Sooners tailback Kennedy Brooks and then was further derailed with a knee injury last season.

He needed a change, his mom says, a new scene, a fresh start. Just like she did herself about 15 years ago.

***

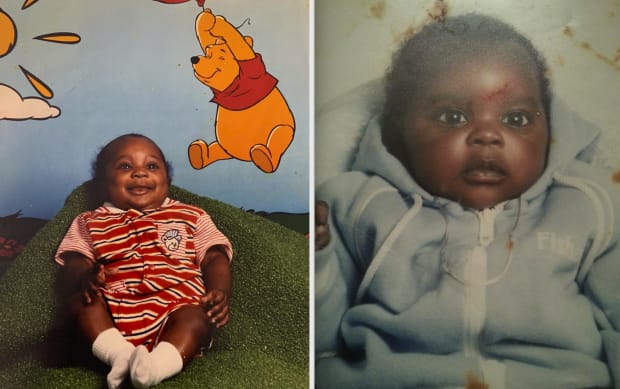

In photos, they look nearly identical.

Trey Sermon never knew his older half-brother, but they bear a striking resemblance in side-by-side photographs of the children at the age of two.

Antonio Brazel died on June 10, 1993. He was two years old.

Sermon was born more than five years later. At some point, when Natoshia Mitchell thought he was ready, she told him and his older sister, Oneisha, the chilling story of Antonio’s death.

As a junior and senior in high school, Mitchell was involved in an abusive relationship with a 30-year-old man. He was violent toward her and even abused her young son. Authorities had made more than a dozen trips to their apartment for violent episodes. She never pressed charges. He threatened her life and threatened her son’s life.

A day before she was scheduled to graduate high school, Natoshia left her young boy in the care of the man. She kissed Antonio goodbye on the morning of June 9, 1993, and told him she loved him.

“I love you too, mommy,” he said.

Hours later, her boyfriend arrived at her apartment door carrying the lifeless boy’s body in his arms.

He lied to investigators, saying Antonio, unrestrained in a car seat, had been thrown against the dashboard of his 1989 Ford Bronco when he made a sudden stop. An autopsy showed multiple blows to the boy’s skull, severe enough that a fitted cap was needed for the open casket.

Prisoner No. 261728 murdered her son.

“I look at it like this: I learned to live with it,” Mitchell says. “I’ll never get over my son’s death. I learned to live with it and move on to show my kids something better.”

The murder of the two-year-old boy gripped the national media back then. Television crews traveled to St. Petersburg to cover the story. Images of the family were plastered on network channels. She knew her children, at some point, would learn the truth. They now know all of the gory details, as hard as it was to tell them. She even walked them to Antonio’s gravesite.

Mitchell is taking her experiences and turning them into something useful. Her book has helped dozens of people, she says. She gets messages from readers all the time.

But she wants more. She has a nonprofit organization called Arise by Faith for domestic violence survivors. She’ll begin a residency in April to complete her doctorate in psychology and plans to open a clinic after graduation next fall. It will specialize in assisting women in abusive relationships and helping those who are not able to produce funds for bereavement ceremonies.

Mitchell will handle the adults, and, daughter Oneisha, four years older than Trey, will treat teens. Billy Shackelford, Trey’s high school coach, says the running back’s resilience comes from his mother. Those who complain about their own life hurdles, those who make excuses and quit, should look to Natoshia Mitchell.

“He and his mom and that family, they find adverse situations in life and they use it as motivation to move forward,” Shackelford says.

This weekend, Mitchell will return home with her granddaughter, and they will attend the national title game. Her family is scattered about in central and south Florida, from Tampa to Orlando to Miami.

This is a homecoming, a return to a place of her first life.

“I’m excited,” she says. “I haven’t been home in a while.”

***

A broken back?

A broken back, the doctor said.

X-rays on Trey Sermon showed a fracture in one of his lower vertebrae, finally discovering the root of all his pain.

This was the worst news. A junior in high school, Sermon had developed into one of the country’s best recruits. College scholarship offers had poured in. And now this?

Surgery wasn’t necessary, but a grueling, months-long rehabilitation process was. It was costly. It was so expensive that Trey’s mother decided to move the family out of their apartment and into an extended-stay hotel. She also sold her car and scaled back her class schedule (she was studying to get her master’s) so she could work more.

“She sacrificed a lot for Trey,” says Chester Ransom, his position coach at Sprayberry (Ga.) High.

The family—Trey, mom Natoshia, sister Oneisha and her then-3 year old daughter A’Mia—shared a one-bathroom, one-bedroom extended stay hotel room for 11 months. Mitchell looks back on it as a good time. The family bonded more than ever. A’Mia made it fun, excitedly waiting for the hotel’s cleaning crew to service the room every other day.

“We always said we were living in luxury!” says Mitchell, laughing. “We did have a housekeeper.”

Secretly, the matriarch of the family cried. Never in front of Trey or her granddaughter. But Mitchell cried often. The family turned to religion during that time more than any other. They prayed for Trey’s back, that it would heal.

Their spirituality has lingered. Before each game, Trey calls his mother and they read scripture together.

Trey’s back eventually got better. Their prayers, Michell says, brought them Tuna Burhanan.

“He was a godsend,” she says softly.

Burhanan, a friend of Trey’s high school track coach, sparked his recovery with a variety of exercises, many of them focused on stretching and expanding his hip muscles. Emotionally, Burhanan became a father figure (Trey’s father, Odell, lives in the Tampa area). Burhanan is still Trey’s mentor and trainer. He traveled to Ohio State this summer to train Sermon and another Buckeye: Justin Fields. He has trained both players, sometimes together, since their high school careers in the Atlanta area.

“I told Trey and Justin in high school, ‘What if y’all end up playing with one another?’” Burhanan recalls. “We all kind of laughed and said, ‘That would be a dangerous combination.’ ”

Sermon has always been an “animal” on the football field, says Shackleford. In fact, five-year-old Trey developed a nickname while playing flag football near Tampa: Terminator. He did enough terminating of other players that coaches moved him from flag to tackle, because he kept grabbing at more than just flags.

His nicknames now are Preacher and Minister (of the End Zone), his mother says, as teammates draw off of the religious nature of his last name. But he’s deeply spiritual as well. His touchdown celebration used to be a simple bow as if he was in front of an altar. He has since changed his scoring celebration to a tap on the wrist as if he’s pointing to a watch.

That means it’s “his time,” Mitchell says. She hasn’t seen this glow on her son’s face since his freshman season at Oklahoma.

“I see that drive,” she says.

So on Monday night, Mitchell will be seated in the stands at Hard Rock Stadium, back near the location of her first life watching her second son compete on college football’s biggest stage. There are good memories here. And there are bad memories here. She left here for a reason, after all.

Mitchell was a witness during the case against the man who killed her first-born son. She testified. Days later, he was found guilty and a fracas broke out in the courtroom. The man’s sister and mother attacked Mitchell, then eight months pregnant.

In the madness, prisoner No. 261728 rushed toward the open courthouse door only to be intercepted by Sermon’s father, Odell. Bailiffs intervened, and order was eventually restored.

Mitchell is back near this place, at home for a short time, this time as a new woman with another son who has captured the nation’s attention.

And there, in a cell some three hours north here, is prisoner No. 261728.