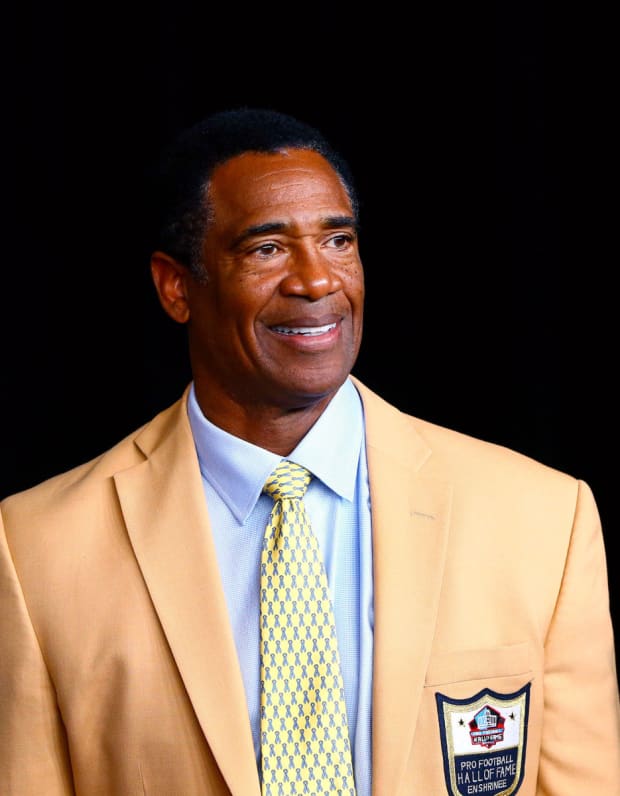

The former Super Bowl champion shares his experience with prostate cancer to encourage others to employ a proactive, preventative approach.

It was supposed to be a normal day in the office for Mike Haynes until a seemingly ordinary task from his boss turned into a life-saving moment.

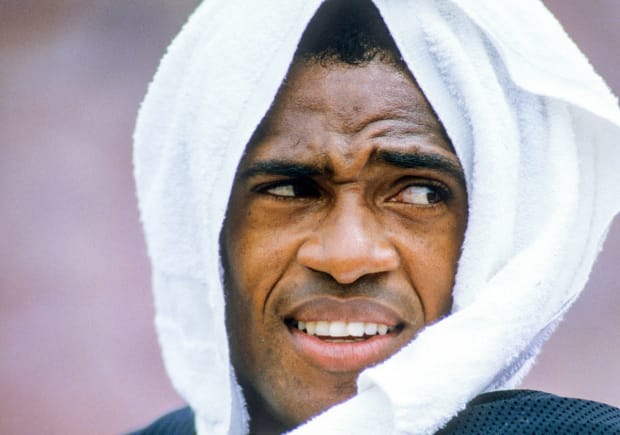

In 2008, the NFL Hall of Fame cornerback—who spent 14 years with the Patriots and Raiders—was working in the player and employee development department, helping athletes transition into and out of the league. At the time, the Pro Football Hall of Fame was hosting a health screening for retired players, and Haynes’s boss asked him to go check on the progress of the event.

But when the former Super Bowl champion arrived, he saw that a majority of the players were talking and hanging out. One of the event workers approached Haynes with a simple request—”Hey, why don't you do it? Maybe you can encourage some of the other guys to do it as well.” Haynes, then 55, agreed and figured that he would get the results from his blood test in a few days. But nearly half an hour later, the doctor called out, “Mike Haynes? Mike Haynes?”

Mark J. Rebilas/USA TODAY Sports

“[The doctor] asked me a lot of questions about my family history and I realized that I didn't know much [about it],” Haynes says. “I knew my grandfather had some kind of cancer, but I didn't know what it was. And that's how it started.”

The doctor told the NFL legend that while the blood test measured the levels of prostate-specific antigen, or PSA—a protein produced by both normal and malignant cells of the prostate gland—it could not alone detect and confirm the presence of prostate cancer. That would require taking tissue samples, which they could not do at the health-screening event. The doctor encouraged Haynes to contact his primary care physician.

When Haynes returned to New York a few weeks later, he followed the doctor’s orders, but his physician was puzzled at why he was there, considering “everything was good” during his visit a few months ago. Haynes explained the screening and the pair discussed his PSA test results: His levels went from two to three-and-a-half in the span of approximately two years. "I thought PSA was an abbreviation for Personal Service Announcement," Haynes says. "I had never heard of it being used [in that] way."

Haynes says the doctor told him, “You're fine for a guy your age, Mike. You're under four, and I think I think you're fine. But to be on the safe side, let's get you a biopsy.’”

Haynes agreed, even though he did not know what all a biopsy entailed at the time. The urologist had him don a robe and lay on his side, asking Haynes to bring his knees to his chest.

“Then he stuck an instrument into my rear to take samples off of my prostate—I didn't know that was what was involved in doing that,” Haynes says. “Had I known, I probably wouldn't have shown up. I don't know for sure if I would have, but I don't think I would because he was already saying, ‘I think you're fine.’ ”

The results came back showing that nine of the 12 prostate tissue samples had cancer.

“I was lucky that my boss sent me over there. I was lucky that the doctor didn't scare me enough where I didn't want to have him test me,” Haynes says. “I realized that [it’s a] slow-growing prostate cancer, and finding out when I did has really prolonged my life. I don't even know if I would have been around this long.”

Andy Hayt/Sports Illustrated

Haynes used to avoid discussing this, but after learning more about the disease, he feels it’s important to highlight that his doctor was Black; they discussed how Black men are more likely to get this disease. “I don't know that I would have felt comfortable talking to a non–African American doctor, so I say it because I think it's something that's important,” Haynes, who is also Black, says.

According to the American Cancer Society in its 2019–21 report, one in seven Black men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime. From 2011 to ’15, the average annual prostate cancer incidence rate was 76% higher for non-Hispanic Black men compared to white men. And a 2018 study found that Black men were twice as likely as white men to die from the disease.

“They were really more likely to die from the disease because they didn't find out they had it until they were in the later stages, and there wasn't too much they could do about it,” Haynes says. “So if you find out in the early stages, it's treatable. Now, there's a lot you can do.”

Haynes, who says he knew someone who died from prostate cancer in his 30s, warns that it should not be categorized as “an old man’s disease,” even though the American Cancer Society has found that the average age of men diagnosed with prostate cancer is 66 years old.

Despite doctors, friends and colleagues assuring Haynes that it was a slow-growing cancer, Haynes made the decision to have surgery. Six months later, in 2009, he had his prostate removed, revamped his diet and exercise regimen and set new targets for himself—and his health.

“Because of sports, I always set a lot of goals, and so I never really had a goal about [life],” Haynes says. “I had a goal of how fast I wanted to be, what kind of game I wanted to have and what kind of season I wanted to have. But I never had a goal with regard to my life, like how long do I want to live.”

After he was diagnosed with prostate cancer, Haynes says he realized he didn't have a goal, so he didn't really care to make better choices. “I could eat sweets all day because … I didn't have a goal to make me stop. I didn't have a goal after I retired to encourage me to get out and exercise and watch my weight and stuff like that,” he says.

Andy Hayt/Sports Illustrated

His wife, a former dancer who also played sports, likes to work out, go on walks and do yoga, and because he likes being around her and enjoys exercising, he continued his active lifestyle in some capacity. But after his diagnosis, Haynes says he really focused on “what I was eating and what I was doing in my body and how some things break down.” He wanted to avoid things that could be avoided, like diabetes (which runs in his family) and hypertension.

So, he gravitated toward more natural sugars, drank more water, ate more leafy greens and even stopped eating red meat. He became a pescatarian, but lately, when he gets his blood drawn, the doctors have told him he’s low on iron. They encouraged him to eat meat, saying a steak a week would be good for him and his body.

Haynes still gets tested regularly, and each time, he has come back clear. Now, he speaks to other players about the importance of these issues and how necessary the screenings are. At first he just spoke to the men, but now, he speaks to the wives and other women, too, so everyone can be informed.

“When I realized that there are things that we can do to increase our lifestyle, it doesn't guarantee that I'm going to live to be 125, but I'm going to be listening,” Haynes says. “And I'll be more attuned to different things that people are saying about diet and exercise and the importance of sleep and things like that.”

Because of the diagnosis, treatment and lifestyle changes, the now 68-year-old is able to better enjoy the eventful lives of his six children, most recently visiting Tate, who plays football at William & Mary. On Sept. 11, Tate tallied six tackles against Lafayette with his parents watching from the stands.

When Haynes talks to anyone about prostate cancer, heart disease or diabetes, he encourages them to know their family health history, especially the younger generations. Because he is a prostate cancer survivor, Haynes hopes his kids seek more information and ask the necessary questions. It’s a very different scenario than it was for him, who happened to be in the right place at the right time.

“It doesn't have to be a death sentence,” Haynes says.

More NFL Coverage: