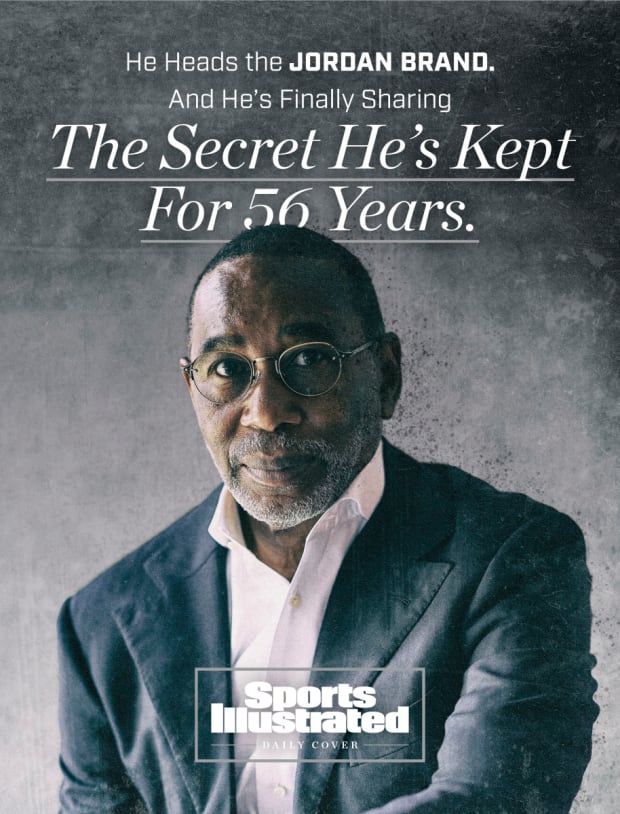

As a teen, Jordan Brand chairman Larry Miller shot and killed a man. He's kept that truth buried, until now.

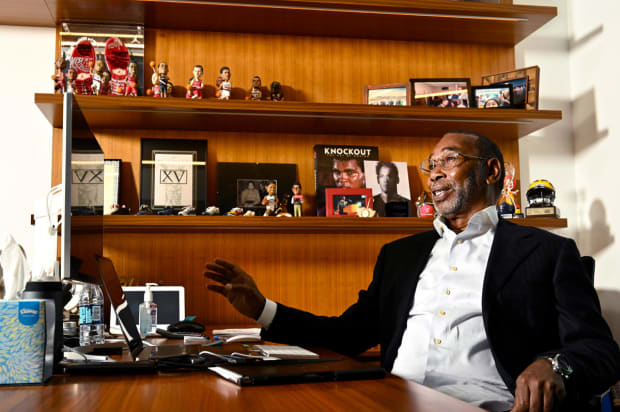

The mementos lining Larry Miller’s office suggest a life of comfort and privilege, of celebrated achievements and celebrity friendships. The autographed red boxing gloves from Muhammad Ali. The commemorative basketball from President Obama. The signed notes from Michael Jordan.

This plush suite, tucked into a quiet corner of the Sebastian Coe building, on Nike’s sprawling campus in Beaverton, Ore., is the primary sanctuary for the man who has piloted the Jordan Brand since 2012, who counts MJ as a close friend and David Stern as a mentor and who has nearly every major figure in basketball (along with Kanye West) on speed dial.

You could spend hours admiring it all, without a single hint of the dark chapter that preceded the journey. Of the years Miller spent in prison, or the horrifying act that put him there. Of a September evening in 1965, when Miller, just 16 years old, stood at the corner of 53rd and Locust streets in West Philadelphia, and fired a .38-caliber gun into the chest of another teenager, killing him on the spot.

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

It’s a secret that Miller, 72, has guarded for more than 50 years. Even as he ran an NBA franchise and then oversaw the transformation of the Jordan Brand, nearly doubling its revenue during his tenure, he kept it from Jordan, Nike founder Phil Knight and NBA executives. He had already, for decades, been holding the truth from his friends and even his own children, for fear its exposure might destroy him. But it is a story Miller now feels must be told, and will be detailed in full in a forthcoming book, Jump: My Secret Journey From the Streets to the Boardroom, cowritten with his oldest daughter, Laila Lacy, set for release by William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins, in early 2022.

In a 90-minute interview with Sports Illustrated, Miller described being haunted by the killing, which he described as utterly senseless. He did not know the victim, identified in the news then as 18-year-old Edward White.

“That’s what makes it even more difficult for me, because it was for no reason at all,” Miller says. “I mean, there was no valid reason for this to happen. And that’s the thing that I really struggle with and that’s—you know, it’s the thing that I think about every day. It’s like, I did this, and to someone who—it was no reason to do it. And that’s the part that really bothers me.”

Revealing his past now, Miller says, will free him to discuss his experiences with at-risk youth and people in prison, and perhaps help steer others away from violence and toward a productive life.

Miller says he wanted the facts to become public on his terms and his timeline, by disclosing it exclusively to SI now, before any details could leak in advance of the book’s publication.

“This was a really difficult decision for me,” says Miller, reclining in a dark-brown leather chair, across from Lacy, sitting on a matching leather couch, “because for 40 years, I ran from this. I tried to hide this and hope that people didn’t find out about it.”

Preserving the secret allowed Miller to build a successful career with companies like Campbell Soup, Kraft Foods and the Trail Blazers, where he served as team president from 2007 to ’12, between stints with Nike and Jordan Brand, where he now holds the role of chairman. But it came at a cost to his psyche: recurring nightmares and migraines severe enough to send him to the emergency room.

“It was eating me up inside,” he says.

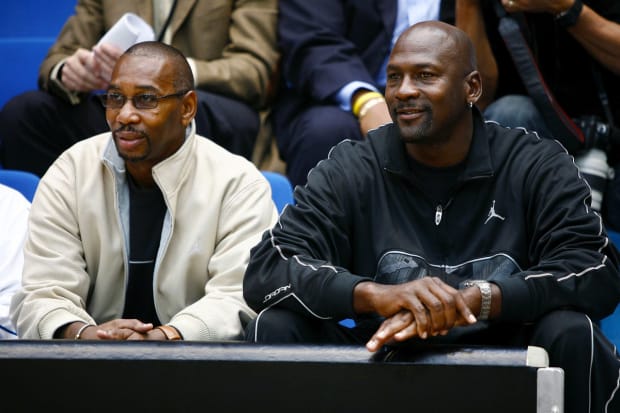

For the last several months, Miller has been gradually informing people in his inner circle—including Jordan, Knight, NBA commissioner Adam Silver and several Nike executives, including Hall of Fame coach George Raveling, another close mentor—to ensure they would hear it from him first.

“I've been blown away by how positive the response has been,” Miller says, calling the process “a real freeing exercise.”

His hope is that his story will provide inspiration for anyone who has been in prison and a lesson for how society views them. “It’s really about making sure that people understand that formerly incarcerated people can make a contribution. And that a person’s mistake, or the worst mistake that they made in their life, shouldn’t control what happens with the rest of your life.”

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

For Miller, the troubles began at age 13, when he joined the Cedar Avenue gang, in the Cobb’s Creek section of West Philly. It had nothing to do with money or drugs or any issues at home, Miller says; his father worked as a supervisor for a drywall company, while his mom took care of the eight Miller children (“We had plenty of food,” Miller says). None of the others got in trouble with the law. The third-oldest, Miller says he had been a model child up to that point—“straight-A student, teacher’s pet … the smartest kid in the class”—but none of it gave him the sense of respect and belonging he desired.

“I started being more interested in impressing people in the street than I did my teachers and parents,” he says. “By the time I was 16, I was just a straight-up gangbanger, thug. I was drinking every day.”

Miller was arrested multiple times, for a variety of offenses, and spent most of his years from ages 13 to 30 in juvenile detention or prison. In the interview, he demurred on discussing his experiences being incarcerated or much of what came after, saying he addresses that in his book. He focused, instead, on the night of Sept. 30, 1965. As Miller describes it, his decision to pull the trigger was an act of retribution. Earlier that month, a younger friend—someone he considered “an innocent”—had been stabbed and killed during a fight with the 53rd and Pine gang.

Guns were rare back then, but Miller had previously acquired a .38 from his girlfriend. So he grabbed the gun, downed a bottle of wine with three friends and went searching for anyone affiliated with the rival gang. He shot the first person they encountered.

“We were all drunk,” Miller says softly. “I was in a haze. Once it kind of set in, I was like, ‘Oh, shit, what have I done?’ It took years for me to understand the real impact of what I had done.”

The newspaper reported that police arrested him soon after the shooting, near where it occurred; Miller tossed his .38 when he saw them coming, but they quickly recovered it. Miller did not know the victim, or whether he had anything to do with the stabbing of his friend, or even whether he had any connection to the 53rd and Pine gang.

“If I could go back and undo it, I would absolutely do that,” Miller says. “I can’t. So all I can do is try to do what I can to help other people and try to maybe prevent this from happening to someone else.”

Just as critically, Miller hopes his evolution can provide hope to others whose lives have taken a dark turn. While in prison, Miller resumed his education. He earned an accounting degree from Temple University at age 30, around the same time he regained his freedom. That is also when his secret was born.

Miller was on the verge of landing a job with Arthur Andersen, the prestigious accounting firm. During his final interview, with the firm’s hiring partner, Miller says he found himself mulling over whether to disclose everything about his past. Soon, he was describing it all—and watching the partner’s demeanor abruptly change. The man reached into his pocket and pulled out an envelope.

“I had an offer here all ready to give to you,” the partner said, according to Miller. “But I can’t give it to you now. I can’t take the chance that somehow this blows back.”

As his dream opportunity evaporated, Miller made a decision: “I'm never sharing this again.”

Miller says he never lied on an application or in an interview. He simply chose to keep the past in the past. When he was hired at Campbell’s, the application asked only whether he had been arrested or convicted of a crime “in the last five years”—a technicality that let him breathe a sigh of relief.

But it haunted him, anyway. In 1997, he went to work as vice president of Nike Basketball, and two years later he became president of the newly launched Jordan Brand. In 2006, he left to become president of the Trail Blazers. He was constantly in the spotlight—standing alongside Jordan, sitting courtside with Blazers owner Paul Allen, attending All-Star Games and NBA galas—and living in constant fear that someone would uncover his past.

“That somebody would tap me on the shoulder and say, ‘Hey, aren’t you ...?’ Or, ‘Didn’t you...?’ And then everything would just kind of come crashing down,” Miller says.

The constant anxiety manifested in nightmares of being arrested or locked in a prison cell—“just that pressure that was building up from keeping this inside and being afraid that it would come out and ruin everything.”

When an invitation arrived to attend a dinner with the Clintons, during Bill Clinton’s presidency, Miller initially hedged, fearing the background check. “I was scared to death,” he says. He eventually relented, sending in his Social Security number and birthdate and throwing his fate to the winds. When the approval came back, he simply sighed in relief.

“I was taking all these high-profile jobs,” Miller says. “I’m like, ‘What is wrong with me? Why am I putting myself out there like that?’ ”

On another occasion, Miller learned that an old neighborhood friend—a reformed gang member who had since gone into law enforcement—had been bragging to a mutual acquaintance at Nike about Miller’s incredible rise from the streets. It was meant as a compliment, but Miller was shaken. “I called [him] the next day and said, ‘Hey, I know what your intention is, but you need to chill,’ ” Miller recalls.

It helped that there’s very little in the public record revealing Miller’s past. Simple Google searches provide no clue about his criminal record or jail time. A deeper search by SI discovered a single newspaper clip, from the Philadelphia Daily News and dated Oct. 2, 1965, headlined, “Youth, 16, Admits Slaying of Rival Gang Member.” The second paragraph refers to the suspect as “Larry Miller, of Catharine st. near 57th, a member of the 56th st. and Cedar ave gang.” It identifies the victim as White, who was “found lying on the street at 53d and Locust sts,” and was pronounced dead on arrival at a local hospital. It said he had never had any run-ins with police.

The memory is never far from Miller’s consciousness. It hit him again just recently after seeing a commercial that included the line, “Every person is irreplaceable.” “I think understanding that just makes you value life,” he says. “And that was one of the differences for me in the street, and I think for a lot of folks in the street: There’s not a value placed on other lives and your own life. We were on a mission to kill ourselves, and it’s just fortunate we didn’t. It just more and more makes me feel sorry about what I did.”

Revealing his past to longtime friends, and particularly Jordan, generated its own sort of anxiety. “I was definitely nervous about sharing with him,” Miller says, “just because I have so much respect and love for MJ.” But the supportive responses from Jordan and Knight gave Miller confidence he could tell other longtime friends, such as Silver.

In a statement to SI, Silver said he was initially “stunned” at the disclosure, having never heard even a “rumor or whisper” of any criminal past. “I then went from stunned to amazed that Larry had managed his long and very successful professional career, operating at the highest levels in our industry, with this secret firmly intact, and was ultimately left with a feeling of sadness that Larry had carried this burden all these years without the support of his many friends and colleagues,” he said.

Silver added that he believes Miller’s experience has given him “a broader perspective from which to judge his life and work…. I think it also made him an especially supportive and understanding friend when it came to dealing with others’ foibles and mistakes.”

Since Miller returned to Jordan Brand in 2012, the company has expanded its roster of female athletes, launched the Jordan women’s line and increased its presence in college and sports outside basketball. He also has overseen the development of the Jordan Brand’s social-impact platform, known as Wings.

“Larry Miller has played an influential role in Nike history and is a beloved member of the Nike family,” Nike CEO John Donohoe said in a statement to SI. “His story is an example of the resilience, perseverance and strength of the human spirit. I hope his experience can create a healthy discourse around criminal justice reform, by helping remove the stigma that holds people and communities back.”

Getty Images for Nike

Hiding the past came with another cost: robbing Miller of the chance to share his most valuable life experiences with at-risk youth. Over the years, he’s worked with groups like the Urban League, Junior Achievement and the Portland-based Self-Enhancement, Inc., often giving speeches about his life and career—but without the most important context.

“I always felt like I was telling half the story,” he says. “And I always felt like I was cheating those people who were listening, because they weren’t getting the full benefit of what this story could be. But I couldn’t tell it.”

He even shielded his three children and his stepson from the full story. But Lacy, his oldest, had lived through much of it. She recalls visiting her father in prison during her childhood, though she didn’t know all the details. Miller told his two younger children when they were in college, around 2003.

About 13 years ago, Lacy started pushing her father for more details and to consider a full public disclosure, in the form of an autobiography. They began working on it in earnest about six years ago.

“He's always been an inspiration to me and to all of us in our family,” she says. “So I just kind of felt it was our duty to share it, to share that inspiration, to share the possibilities with other people.”

At times, the process got so intense that one or both of them would have to step away. “Sometimes it even would make me question, Is this really something that we need to do?” Lacy says. “Because that the last thing I would want to do is to see him in pain, reliving these horrible stories. But I felt like there was a greater need.”

Discussing it proved therapeutic; the nightmares and migraines started to fade, and then ceased altogether, as the writing process unfolded. He says he is planning to reach out to White’s family, as well.

Jeff Hanisch/USA TODAY Sports

With the secret out, Miller says he hopes to increase his work with incarcerated people and underserved youth. He also wants to help reinstate some of the educational release programs that allowed him to get his degree while in prison. To that end, Shauncey Mashia—Jordan Brand’s global senior manager for Black community commitment—sat in on the interview, taking notes for how to invest some of the $100 million that Jordan pledged last year to promote social justice. Some part of that fund will be used to help Miller spread what he says is his most vital message: that everyone deserves a second chance.

“It’s not about me,” he says. “Some of the most creative, intelligent, smart people I know are people I’ve met in jail, because there’s all this talent and all this ability that I think is being wasted inside the jails.”

As Miller tells his story, it’s hard to square the two Larry Millers: the self-described “gangbanger” who didn’t value his own life vs. the one sitting here today in this executive office, in wire-rimmed glasses and a dark blazer, a pair of ultra-rare Air Jordan 1s on his feet and images of Jordan decking all four walls—including a striking floor-to-ceiling mural of Jordan soaring to the rim during the 1988 slam-dunk contest.

Over the couch is the Jordan “Wings” poster. And inscribed on the back wall—over the signed boxing gloves of Ali and Roy Jones Jr. and an autographed photo of Tommie Smith and John Carlos, and below a green Do the Right Thing street sign (a gift from Spike Lee)—is one of Jordan’s most famous quotes: “I’ve failed over and over again in my life—and that is why I succeed.”

Is Miller nervous about this story, this book? Yes, he says. But for the first time in his life, he is ready to present both versions of himself to friends and peers and the public at large, with the hope that others can follow his path.

“It’s freed me,” he says. “I feel the freedom now to be me.”

• 75 Years of NBA Coulda-Beens

• Trae Young is the Hawks' Torchbearer

• Luka Is Learning From the Best