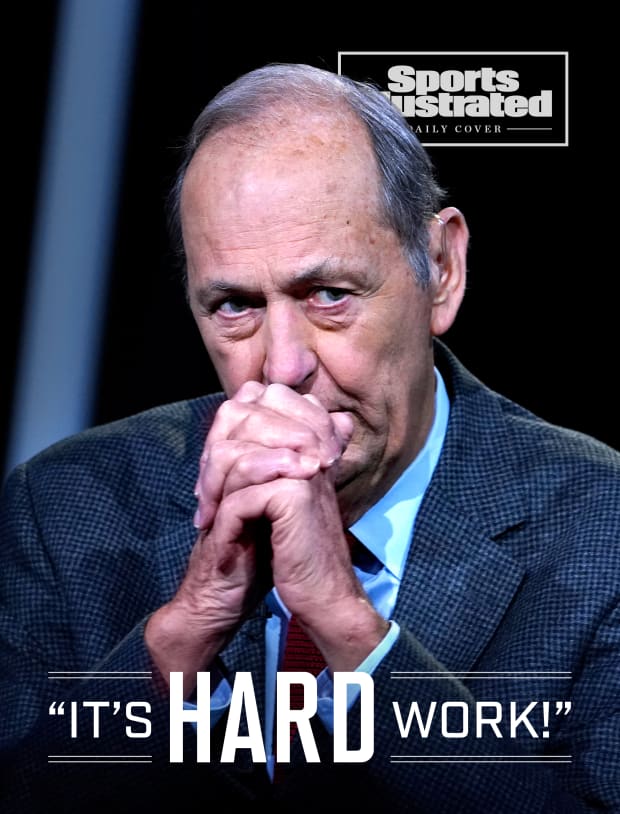

The former senator knows what it means to be elected on sporting fame. He knows what comes next, too.

A famous athlete, running for the U.S. Senate in the state where he was a collegiate legend, despite grumblings that he had moved there just to fulfill his political aspirations.

Today, that’s Herschel Walker in Georgia.

But once, it was Bill Bradley in New Jersey.

“I don’t begrudge anybody using their fame to run for office, whether you’re Ronald Reagan or Jack Kemp or me,” Bradley says, referring to the 40th U.S. president, a former actor, and the Bills star who later served in Congress and was Bob Dole’s running mate in 1996.

Bradley embodied the allure of the athlete turned politician before he ever turned politician. In 1966, when he was 22, Sports Illustrated floated the possibility that he might be president someday. Such speculation increased after New Jersey elected Bradley to the Senate in ’78, but when he finally ran, in 2000, he was soundly defeated by then Vice President Al Gore.

John Lamparski/Getty Images

Looking back, people were mostly excited by the idea of Bradley. He’d led Princeton to the Final Four, he became a Rhodes scholar and then he won two NBA championships with the Knicks—an unparalleled and incredible life. But Bradley himself did not excite people. He was bright, genial and empathetic, and New Jersey eventually reelected him, twice. But he also once admitted that he had “the rhetorical skills of an inmate of Madame Tussauds wax museum.” At the 1988 Democratic National Convention he was assigned to talk about the role of the presidency in American life, and he later wrote: “I took the assignment seriously, and I put the crowd to sleep.”

Bradley’s basketball skills catapulted him to the Senate, but they also gave him sizzle that he never would have had otherwise. His ambition was largely intellectual, and he was drawn to big ideas; one criticism of him in the Senate was that he was not calculating enough. Bradley served alongside more than 200 other senators in his time, and they ranged from brilliant to bumbling, but he says he never met a senator as overmatched as Herschel Walker.

Here is Walker, on why he thinks he can defeat Sen. Raphael Warnock in a runoff Dec. 6 for a seat Warnock won in 2021: “One of the first things [Warnock’s administration] did—and I think people need to know this—is they decided they were gonna give up all the energy. By him going out and giving up all the energy, now we’re not energy-independent anymore, which started the whole downfall. … This is one of the most environment-driven countries in the world, but yet we’re walking on all the resources we have underneath our feet and we won’t say, ‘Hey, guys, we gotta come out of this.’”

And here is Walker, on climate change: “Since we don’t control the air, our good air decided to float over to China’s bad air, so when China gets our good air, their bad air got to move. So it moves over to our good air space. Then, now, we got to clean that back up.”

And here is Walker, on gun violence: “It’s a person wielding that weapon. You know, Cain killed Abel, and that’s a problem that we have. What we need to do is look into how we can stop those things. You know, you talked about doing a disinformation—what about getting a department that can look at young men that’s looking at women that are looking at their social media? What about doing that? Looking into things like that and we can stop that that way. But yet they want to just continue to talk about taking away your constitutional rights.”

Walker’s comments are not gaffes. This is not George W. Bush mangling the occasional sentence, or Joe Biden dropping the wrong name in a speech. This is the rambling nonsense of a man who lacks a rudimentary understanding of the issues, and it’s alarming—even before you consider the accusations of domestic abuse, or the allegations that Walker, who is running on an anti-abortion platform, paid for his ex-girlfriends’ abortions, or his fumbling denials.

Megan Varner/Getty Images

“I’ve seen plenty of people make mistakes,” Bradley says. “I haven’t seen anybody make as many mistakes. It seems to me that [Walker] was not prepared to run for office, and certainly not this office. I don’t know what he’s done over the years to try to understand the world or understand his country or understand politics or the economy.”

Let’s be straight here. Bradley is a Democrat, and Walker is a Republican. When people say they want to put politics aside, they usually mean that they want to put your politics aside. If you choose, you can dismiss everything Bradley says because he is a Democrat talking about a Republican.

But Bradley was also a senator for two decades. He understands how the body operates. My question to Bradley was not about whether he wants Walker to win or lose. It was about what happens to Walker if he wins. Reagan, Kemp, John Glenn (the astronaut turned senator) and Bradley all transitioned from celebrity to politician. The difference with Walker is that his fame—and his endorsement from former president Donald Trump—seem to constitute the entirety of his appeal.

What happens if Walker stops running and starts serving? Bradley puts it another way: “I don't know why somebody doesn’t ask him: What committee do you want to be on? Why?”

Thirty-five-year-old Bill Bradley wanted to be on the Senate Finance Committee, and when he walked into the Senate in January 1979, he got his wish. On one of his first days on the job, he sat at the end of a table as people testified about provisions of a portion of a multilateral trade negotiation known as the Tokyo Round. Bradley says now: “I did not understand one word. It was sad.”

Competence is a boring word in politics. Michael Dukakis once said the 1988 presidential election would come down to competence, and he was ridiculed for it. Competence does not really get many people on either side of the aisle elected. But Bradley soon realized that competence was Congress’s most valuable currency.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

“You get exposed easily,” he says. “If you don’t know what the hell you’re doing, it’s not long [before] everybody knows: Well, he’s over in this category.”

Bradley’s strengths—what got him to the Senate—were his intellect, curiosity, beliefs and ethics. And his famous name. He realized quickly how little that fame, or his basketball career, meant to his peers. “That’s yesterday,” he says. “It’s like saying, Hey, tell me all about high school prom. That’s irrelevant.” Bradley made a conscious decision to never talk about basketball in the Senate, to the point where it became a bit of a joke. Senators would try to make small talk and ask him about the NCAA tournament, and he wouldn’t even discuss it.

“You don’t go around talking about sports all the time,” he says. “You’ve got to do the work—people sent you there to do the work. The work means 14, 15 hours a day, mastering the substance of committees, and learning about the world and making judgments about your state and how you help your state.”

Bradley liked the work—even now, his voice rises a bit when he says the word work. He can tell you all sorts of stories about the work, and some of them might bore you, but that is sort of the point. Being a senator is like coaching a football team, in that the public sees only a sliver of what you do. Most Americans follow elections, but Bradley says: “You don’t see the job. Committees. That’s where the substance is.” Since the start of 2021, the Senate has held more than 800 votes. And that doesn’t count all the issues that didn’t make it to a full-Senate vote.

“There are two kinds of senators,” Bradley says. “There’s a senator who’s basically a pol trading votes, right? And there’s a senator who knows something. The senator who knows something has more power, because nobody will challenge him—because [people are] afraid of being embarrassed.”

Bradley realized early on that he had to do a lot of studying just to avoid being embarrassed. In 1986 he sat with a yellow legal pad and asked 22 questions of Wyoming Senator Alan Simpson, a Republican, all of them about the bill that would eventually become the Immigration Reform and Control Act. When they were done, Bradley told Simpson that he agreed with 16 of his 22 answers, and that he would support the bill.

Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated

“We both had to know what the hell we were talking about,” Bradley says. “He was the true expert, but I had to know enough to know the right questions. … If all you know are three points on a card, you’re not going to be effective.”

The political climate today is so polarized that Americans seem to view every candidate as either My Side or The Other Side, but it’s not that simple. Bradley tells this story: In 1992, he wrote legislation that became part of the Freedom Support Act, which funded trips to the U.S. for high-school-age kids from the former Soviet Union and the Baltic States. Every year after the act passed, Bradley had to make sure it remained funded, which meant lobbying the chair of the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs: Kentucky’s Mitch McConnell.

“We’d talk and work it out,’ Bradley says. “And every year, I got the money. [But] you’ve got to know what you’re talking about. There is no substitute.”

The work involves schmoozing donors and campaigning for colleagues, but also helping constituents who haven’t received their social-security checks or who have small but important requests.

“When you’re a senator, you help people,” Bradley says. “And helping people isn’t just being in Washington, giving speeches or going on TV. It’s doing the nitty-gritty stuff—having a staff that knows how to [navigate] the bureaucracy, how to put the pressure in the right places, how to get the things you need for your constituents. It’s hard work! It’s noble work! And unless you like that, and understand that, you won’t be an effective senator.”

Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated

One more story. This was 1996. There had been a gas explosion in New Jersey. Bradley tried to add an amendment onto an appropriations bill to help with recovery efforts. He had been in the Senate for a long time; he knew the amendment was not germane to the bill. He says today: “I shouldn’t have done it. But I had to fight for my state. So I did.”

Mississippi Republican Trent Lott, the Senate majority leader, asked Bradley repeatedly to take the amendment down. Bradley refused. Finally, Lott made a deal: Take your amendment down, and I will make sure that the Senate passes the funding properly. Bradley took it down. He also left the Senate that year.

The next year, while Bradley was teaching at Stanford, Lott’s chief of staff called him to let him know that the Senate had approved his request.

That was a different time, less tribal, but Bradley doesn’t think the Senate has changed as much as people believe. Expertise still matters. Relationships still drive the process. He says, “If everybody’s lying to everybody, it’s no fun. And you get very little done.”

That is the group Herschel Walker is seeking to join. That is the work he is asking to do. Bradley says, “I just hope that there are enough Georgians who recognize that they wouldn’t be getting a full-time senator. And every state needs a full-time senator—two of them—if they’re going to be represented well.”

Last week, after Bradley and I spoke, I emailed Walker’s communications director, Will Kiley, with a single question: “What committees would Herschel Walker like to be on if he is elected senator?” I have not heard back.

• Inside The Upside-Down World of Long Snappers

• The Long-Forgotten First Chapter of the Grizzlies

• Robert Griffin III Is ESPN’s Next Big Star

• The Full Drew Timme Experience