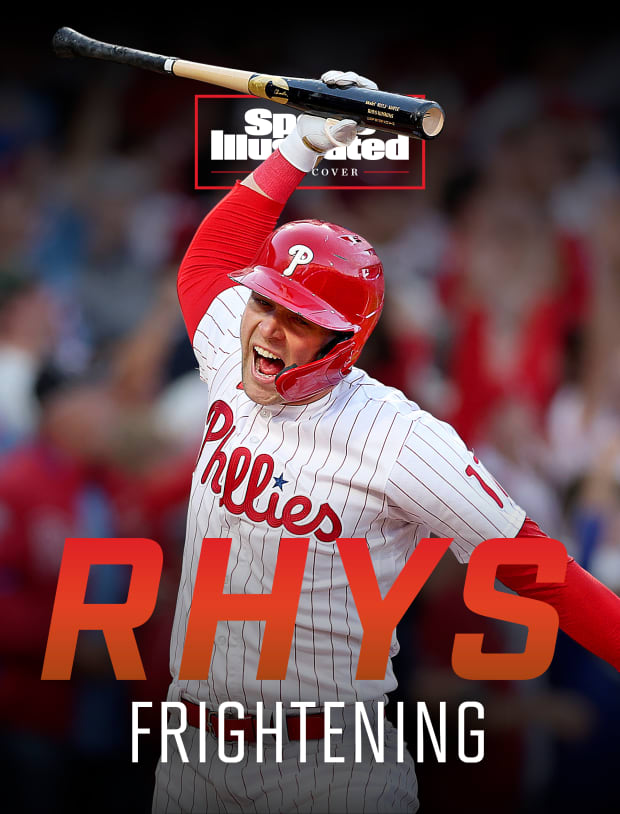

The Phillies went from horrifyingly bad to scary-good, and he’s the only hitter who’s been here through it all.

Their home run celebration is simple. It is almost too simple to be called a handshake, really, just a few movements that look so instinctive they might as well be automatic. When Phillies third base coach Dusty Wathan sees Rhys Hoskins hit a ball out of the park, he waits for the first baseman to round the corner toward home and then he slaps his hand and gives him a pat on the butt. See? That’s all it is.

This simple gesture, though, was chosen deliberately. It means something to both of them, and it has been shaped by years of waiting and hoping and working.

It started when Wathan was Hoskins’s manager with the Double A Reading Fightin Phils in 2016. He hadn’t yet coached in the big leagues, and, of course, most of his roster had never been there, either. So Wathan studied how the Phillies’ third base coach at the time, Juan Samuel, celebrated home runs—a quick hand slap followed by a pat on the ass. It was nothing special. But Wathan decided he would mimic it with his team. This is getting you ready for the big leagues, he’d joke. So you’ll know what to do after your first home run in Philadelphia. It was a reminder of what they were all working toward.

Patrick Smith/Getty Images

That was a long time ago now. In 2016, Bryce Harper and Dusty Baker were both still with the Nationals, this Astros core had yet to make a World Series and Dave Dombrowski was just getting started with the Red Sox. Meanwhile, the Phillies had plans, and Hoskins was a key part of them. Almost nothing went as they or he expected in the interim. Yet here they are now, six years later, about to host Game 3 of the World Series.

Eventually, Wathan became the winningest manager in the history of Double A Reading, and he followed that with a year managing Triple A Lehigh Valley. He’s now in his fifth season on the big league staff. There are some organizations where that arc would mean he’d coach in the majors the kids he managed in the minors. Except that’s not how it worked out here. The Phillies have used the last few years to cycle through managers and general managers and models of roster construction. There has been considerable turnover. Which means that of all the position players on the Phillies, there is just one who was managed in the minors by Wathan: Hoskins.

And so Wathan congratulates everyone who hits home runs with hand slaps and butt taps. For Hoskins, though, it’s a little more, a reminder of how far he has come—a symbol of where he has settled as the team has added and subtracted and shifted around him.

“I always stayed with it,” Wathan says. “Just for him.”

This is how Wathan has celebrated with Hoskins after each of his home runs this October. There was a handshake like this after the cathartic bat spike in Game 3 of the NLDS, after the pair of dingers in Game 4 of the NLCS, after the shot that opened scoring the next day in Game 5, helping to send the team to the World Series.

There was also a Wathan handshake for so many Hoskins home runs before these. There was one for home runs where a loss seemed inevitable, and for home runs where the season itself seemed futile and for home runs where the stadium had booed the first baseman when he walked to the plate.

It’s the collective imprint of those handshakes that has made Hoskins’s big October moments seem so apt. Hoskins is not the most naturally talented hitter on this roster. He is not the highest paid or the most obviously beloved. But he is the one who has been here the longest. He is the one who has bridged the eras of this franchise, who carries the institutional knowledge, who symbolizes what it means to wait.

All of which is to say there are other players on this roster who have received playoff home run handshakes from Wathan. Yet only Hoskins really, truly grasps what the handshake means, in more ways than one.

Bill Streicher/USA TODAY Sports

It can be tricky to summarize just what Hoskins represents to Phillies fans, with a history that holds plenty of complications, quirks and contradictions. Perhaps the best way to capture it is this: No one has received a more even mix of cheers and boos at Citizens Bank Park this October. (Shortly before his mammoth home run in Game 3 of the NLDS, a fan yelled up to the press box, “Trade Hoskins!” seemingly frustrated with a costly error the first baseman made in the previous game.) He has undoubtedly provided some of the biggest highlights on that field this month. Yet there might not exist a highlight big enough to fully erase the angst, the frustration, that keeps fans occasionally booing.

Some of that has to do with the kind of player Hoskins is: There have been angsty fans as long as there have been bat-first guys who strike out rather frequently and are prone to mistakes on defense. But it has almost just as much to do with what he symbolizes: Hoskins is among the last remaining connections to a Phillies rebuild that never really took off. He’s a reminder of how much the franchise has changed, of expectations never met, of all that did not work out. Yet Hoskins worked out enough—just enough—to stay through it all.

That dynamic began almost as soon as Hoskins got started in Philadelphia. He was called up at a low point for the 2017 Phillies. He went on to have one of the best debuts in major league history—Hoskins is still the only player ever to hit 11 home runs in his first 18 games. The team lost 96 games. Yet it established a focal point: Hoskins was suddenly expected to be a leader on a roster that did not have many.

“He came up at a really hard time, when we were well below .500,” says pitcher Zach Eflin, one of the only members of the team who has been around longer than Hoskins, called up a year before. “And he was the guy—he was on all the billboards.”

That was not something Hoskins had ever anticipated. He’d enjoyed a strong career in the minors, but the California native had been a fifth-round draft pick out of Sacramento State, the only college to offer him a scholarship. It was not a background that had ever suggested he might be positioned as the face of a team in his first year in the majors.

“He didn’t grow up like Bryce Harper,” Wathan says. “So it was kind of a thing that he had to accept.”

Greg Nelson/Sports Illustrated

And it was hard. He was initially asked to play left field, a position where he did not have much experience, just so they could fit his bat in the lineup. He later struggled to live up to the standard he had set during his torrid start. The expectations on him were high—perhaps unfairly so—and it was all he could do at times not to collapse under them. The team as a whole struggled often in those early years, and, because he’d been positioned as its face, he tended to bear that weight most heavily. When Hoskins made a mistake, it seemed to stick out. Yet he kept going and managed to find his footing—if not quite becoming the player some had hoped he might be after his debut, then growing into a quality, everyday big leaguer all the same. The team changed around him. Hoskins worked hard to be able to stay.

“There’s a ton of perspective, I think, to gain from that,” Hoskins says. “It’s something I definitely take pride in that, hey, I was able to be good enough to stay with the same organization. But also that I’ve been able to do it with the help of a lot of people within the Phillies organization—just to kind of navigate Philly, navigate what it’s like to play on the East Coast, what it’s like to be a major league baseball player—it’s beautiful, really.”

Hoskins will not turn 30 until next March. It has been only eight years since he was drafted. Yet he’s survived a few careers’ worth of changes in Philly, and then some. He has now played for four managers in the big leagues and under multiple front office regimes. While Hoskins was once at the forefront of a youth movement, when it seemed clear that was not working, the club pivoted to chase players outside the organization instead: Harper, J.T. Realmuto, Zack Wheeler. There were yet more changes still to come after those big moves. Hoskins has been a bridge across it all.

“Rhys has seen everything,” says Phillies rookie shortstop Bryson Stott. “Managerial changes, GM changes, he’s seen it all. And he just keeps going. … He’s one of our leaders. He’s someone we look up to and look to when things aren’t going right. And for him just to keep going, and take big swing after big swing, has been awesome.”

That has made some of his October success seem especially poignant. Hoskins embodies the ups and downs of this franchise more than perhaps anyone else has over the last few years. He can embody them even within the space of a single game.

“There have been some moments where he’s made a critical error or struck out in a big spot. But this guy is—he’s ferocious, he’s a competitor and he comes to play every day,” says Phillies manager Rob Thomson. “He’s such a good person that whenever he does something right or good, I cheer louder than I cheer for most guys.”

As the team has finally been able to enter a new era of sorts—calling up homegrown talent from a farm system that looked barren just a few years ago—Hoskins has been able to impart all he’s learned. Here’s how to deal with the boos. Here’s how to keep going after failure. Here’s how to learn to love playing in this town. The young players know what that means coming from him: Hoskins has lived it. And it’s made it that much sweeter to watch his big home runs this postseason.

“Just as a teammate, I’m excited because it’s helping us,” Phillies third baseman Alec Bohm says. “But as a friend … I couldn’t be happier, because I’ve heard him get booed, I’ve seen him struggle, I’ve heard, ‘This guy stinks. We need to get rid of this guy.’ So I’m super happy for him.”

Greg Nelson/Sports Illustrated

Hoskins has spent considerable time this season with hitting coach Kevin Long. A new hire this winter, Long did not know Hoskins well before taking the job with the Phillies, but the pair quickly grew close.

At one point this season, Long showed Hoskins a video of him striking out. The two have watched a lot of video together this year—particularly to eliminate an occasional bad habit of adding a loop into his swing—but this time, the coach told him just to watch and describe what he saw, no particular feature to look out for. Hoskins scrutinized his stance. He thought about the pitches he had been hunting. He analyzed his swing. No, Long finally told him, you’re missing it.

You’re hanging your head after every whiff.

Why? Long asked. You’re not out when the count is 0–1. You’re not out when it’s 0–2. Hell, even when you are out on 0–3, you still have another plate appearance coming up. Why are you hanging your head like that? There’s no reason for it. You have to keep going. There’s only so much you can control about striking out—a game of failure and all that—but you can control every part of keeping your head held high as you walk away.

“He’s hard on himself,” Long says. “He just wants to be really, really good and really, really consistent. Well, he is really good. … But he’s beating himself up when he’s not doing it, and that could throw him into these huge tailspins.”

The consistency has not always shown up on the field this year. Mentally, however, Long says there has been a world of difference.

“I think it’s the maturity and how much he’s learned about himself,” Long says. “Getting rid of his negative thoughts and trying to do something more than he’s capable of—I think that’s gone.”

Hoskins scored the first run in this World Series for the Phillies. (Who else?) The game also saw him strike out once and leave three men on base. But while Long and the rest of the coaching staff were proud of the initial hit that got him in scoring position, pleased with what he was able to do overall, here was what stood out the most: Hoskins held his head high throughout.

More World Series Coverage:

• Philadelphia: Welcome Home, Chas McCormick. We Hope You Lose.

• How Alex Bregman Found His Footing and Started Raking Again

• Jose Altuve Is Back—Just in Time to Save the Astros

• The J.T. Realmuto Game Has the Phillies Ready to Shock the World

• Justin Verlander Crumbles Yet Again in the World Series