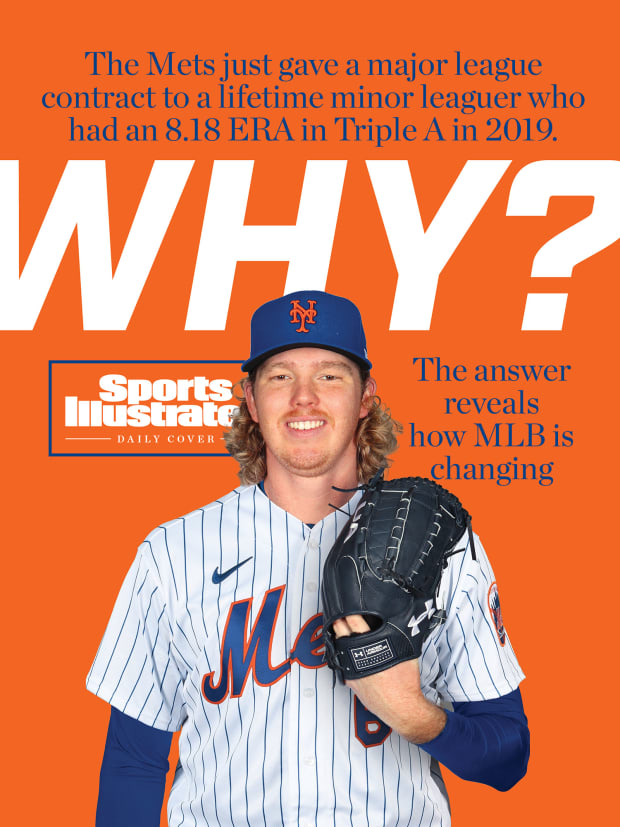

The Mets won a bidding war for Sam McWilliams, who's never pitched in the bigs and posted an 8.18 ERA in Triple A last year.

Who is Sam McWilliams? And why in a slow free-agent market during a pandemic did half the teams in baseball engage in a bidding war for a 25-year-old pitcher with no major league experience and an 8.18 ERA in Triple A in 2019, when he last pitched competitively? And why did the New York Mets hand him a major league roster spot and more money than they paid Pete Alonso after his historic rookie season?

The answers are more than just interesting. They reveal insights about what is going on with analytical data, pitching trends, scouting trends, the reputation of the Tampa Bay Rays and how new Mets owner Steve Cohen and president Sandy Alderson are changing how the team does business.

They also reveal how McWilliams, a six-year minor league free agent on his fifth organization, landed at the intersection of these changes with perfect timing.

“I really had no idea what to expect,” McWilliams says. “This was my first time being in the driver’s seat as far as where I would go. I didn’t know what to think at first. Once the calls started coming in, it was fun and interesting. I’m really grateful it worked out the way that it did.”

Alderson told Sports Illustrated, “To get the player, we went a little beyond where we originally thought we were willing to go.”

It may sound odd that McWilliams attracted so much interest and money without throwing a competitive pitch in 2020. Actually, the interest happened because he did not throw a competitive pitch this year. McWilliams spent the season at the Rays’ alternate camp in Port Charlotte, Fla. It was there that he changed his pitching style and collected pitch-tracking data on his phone that he could show to other teams.

Tampa Bay is regarded as one of the most advanced pitching organizations in baseball. Among the undervalued pitchers they acquired and turned into successful big league pitchers are Tyler Glasnow, Pete Fairbanks, Ryan Yarbrough, Nick Anderson, Colin Poche and Ryan Thompson. What MIT is to engineering majors the Rays are to pitchers. There is a halo effect. McWilliams’s value was enhanced by his development in the Rays’ system.

“Definitely,” he says. “The Rays in general were great for me, in the sense that getting traded over there after not being exposed to too much [information] before. Over the past two or three years there everything just kind of blossomed for me. I developed a much better understanding about pitching, especially what we can’t see with the naked eye.”

One executive from a club not involved in the bidding admitted he was surprised that the Mets gave McWilliams $750,000 and a major league deal. As the executive clicked away at keys to summon reports on McWilliams from the team’s proprietary database, he said, “All the pitch characteristics and info under the hood are just okay. Fastball 94 [mph] … slider can be really good, but throws it only 38% of the time … has all his options left, which is good … decent results …

“All the stuff grades out to around average to slightly below average. If the idea is to create depth, it’s a good move. These days you need 20-some odd pitchers on hand who you know are capable of competing in a major league game right now. I know Sandy is looking to improve their depth, so that fits. But he’d be about 20th on most teams from that depth standpoint.”

The Mets are betting McWilliams is much more—and they beat out many other teams who were ready to make the same bet.

***

McWilliams’s path to the Mets covers seven seasons, five organizations, two trades and one failed cameo. It began in 2014 with the second scrimmage of his senior year at Beech High School in Hendersonville, Tenn. The opposing pitcher was Justus Sheffield of Tullahoma High, a highly touted Vanderbilt recruit who would be drafted 31st overall that year by the Cleveland Indians. About two dozen scouts flocked to the scrimmage. They noticed the less heralded McWilliams, a 6-foot-7 right-hander who could throw in the low 90s and had committed to Tennessee Tech.

The Philadelphia Phillies selected McWilliams in the eighth round of the draft–the only high school player they chose among their first 27 picks that year. McWilliams signed for $200,000 and headed for rookie ball in Clearwater, Fla. At 18 years old, he was the only player on the team signed out of high school. Alone and unsure, he cried when he first arrived.

A starting pitcher, McWilliams spent two seasons at Clearwater without distinction, especially when measured by his ability to miss bats. He averaged 4.8 strikeouts per nine innings. In November of 2015, in his first move as Phillies general manager, Matt Klentak traded McWilliams to Arizona for veteran pitcher Jeremy Hellickson, who would make 32 starts for the 2016 Phillies and lead them in wins (12).

Two and a half years later, in May 2018, Arizona traded McWilliams and Poche to Tampa Bay to complete a three-way deal that sent Steven Souza Jr. to the Diamondbacks. Seven months after that, Kansas City selected McWilliams in the Rule 5 draft. But the Royals returned McWilliams to Tampa Bay after watching him yield 10 runs in 4 2/3 spring training innings.

That year, 2019, McWilliams pitched well at Double-A Montgomery (6–3, 2.05) to earn a promotion to Triple-A Durham. It did not go well. He gave up 72 hits in 44 innings, leading to that ugly ERA (8.18) and a 1–6 record.

After five years, four teams and 535 pro innings with a 3.85 ERA, McWilliams was just another fringe starting pitcher in a game that increasingly values velocity and swing-and-miss stuff. He averaged seven strikeouts per nine innings.

After that 2019 season, McWilliams consulted with one of his Montgomery teammates, Tyler Zombro, an undrafted pitcher who had studied biomechanics and physical therapy at George Mason. Zombro is part of the next generation of tech-savvy pitchers: They speak analytics, biomechanics and pitch characteristics as a first language. Zombro also works a side gig at a Herndon, Va., training academy as a consultant to high school, college and professional pitchers. Teammates call him “Coach Z.” McWilliams visited Zombro at his Virginia facility after the season for a high-tech assessment and for training program recommendations, “which we had already been talking about for a while,” McWilliams says.

“He had a good idea of what we wanted to address as far as anatomical deficiencies and movement patterns,” McWilliams says. “So we got to work from there on basically getting me into better [and] more efficient positions.”

Supported by data from the Rays and Zombro, McWilliams decided in 2020 to change how and what he threw.

“I had thrown two- and four-seamers my whole career,” he says. “After last year I just felt both had become inconsistent. Throwing the two-seamer, it made the four-seamer inconsistent, causing me to get almost on the side of the ball.

“So that winter going into 2020 I decided to scrap the two-seamer. I just worked on getting behind the four-seamer and commanding it. We had talked about it with the Rays before, as to what gets the best results. The data showed that the two-seamer was average to plus sometimes, but it wasn’t anything to generate whiffs.

“My main goals going into camp were to make the slider as hard as possible while still getting that glove side cut, and with the fastball it was all about chasing that vertical movement while getting behind it as much as possible to get true backspin.”

Analytics have changed pitching. They have transformed pitching from a horizontal game (in and out) to a vertical game (up and down) to combat the Launch Angle generation of hitters who chase slug, not batting average, by getting the ball in the air with backspin. The Rays are the masters of modern pitching to defeat the Launch Angle game: high-spin fastballs up to get above swing planes, followed by premier breaking balls down to get under them.

Careers have been transformed. Justin Verlander and Gerrit Cole added a rocket stage to their careers when analysts in Houston showed them data and video detailing how they were doing a favor to hitters by throwing them two-seamers. (They junked the pitch, and their four-seamers improved.) Charlie Morton became better than ever once he stopped trying to be a sinker ball specialist.

From 2015 to 2019, the use of two-seamers and sinkers dropped from 21.2% to 16.0%. In raw numbers, that’s a drop of 31,958 pitches, a decline of 21% in the relative eyeblink of five seasons.

Why has the pitch fallen out of favor so fast? Follow the numbers. Last season batters hit .286 against two-seamers and sinkers and .236 against all other pitches. If you are going to throw a pitch that adds 50 points to hitters’ batting average, it had better be an exceptional one—or don’t throw it at all.

McWilliams is one of the many pitchers who arrived at this epiphany.

“In games this year all I threw were four-seamers and sliders,” he says.

The pandemic meant those “games” were 10 a.m. scrimmages at the Rays’ alternate site in Port Charlotte, Fla. Every pitch was measured with Trackman, a laser tracking device that records the speed, spin and shape in military-grade precision. The information is sent to each pitcher’s Dropbox after every game. McWilliams tracked these reports on his phone to see he was gaining velocity and spin on both his fastball and slider. His four-seamer touched 98 mph. His command and confidence improved. The Rays began to use him as a reliever.

“The alternate site was a lot of fun,” he says. “They made it really competitive, even though it wasn’t the best environment at 10 a.m. in an empty ballpark in Port Charlotte in the summer.

“I felt like I made real strides, especially my overall feel in terms of the awareness of my body throughout the delivery and of the strike zone. And how to approach hitters and understand tendencies. One of the benefits for me at the alternate site was I was facing my own teammates. So we’d have a scrimmage, and after it you could sit down next to a guy and talk about what they saw or how the ball was coming out of my hand from their perspective. It was really beneficial to get that instant feedback from hitters.”

No longer going back and forth between two-seamers and four-seamers, he noticed the improvement on his four-seamer. It was becoming the swing-and-miss pitch he had lacked.

“I feel like even just being behind the pitch with my hand more consistently, it was that much easier to command it,” he said. “I didn’t change much mechanically. All I did was get a little more upright with my posture, but that wasn’t necessarily anything that I wanted to strive for. It just happened naturally.”

Injuries wracked the Tampa Bay pitching staff. In a 60-game season the Rays used 25 pitchers. McWilliams wasn’t one of them. He did briefly make it out of Port Charlotte, being placed on the taxi squad in August. But after joining the team in Buffalo, he never made the active roster.

After the season, the Rays put 22 pitchers on their 40-man roster. They are so deep in pitching talent that McWilliams wasn’t one of them. He was free to find another team.

***

One important scouting question needed to be answered in this strange season: How would clubs value a free agent pitcher when they never saw him throw a pitch in 2020? Teams are permitted to share video and Trackman data from alternate site camps. McWilliams himself assisted if teams needed proof of how much he improved in 2020.

“Thankfully I had a lot of my info saved from my 2020 file on my phone, and that was really good to have,” McWilliams says. “It was good to be able to show them my video and metrics.”

The offers started pouring in. The Mets were not among them. It was only after Cohen closed on the purchase of the team Nov. 6 that Alderson and his staff reached out to the pitcher.

“I really didn’t hear from the Mets until the last minute,” McWilliams says. “It was only after the change in ownership.”

McWilliams had no direct ties to Mets decision makers. He did know Jarrett England, who has been a Mets area scout working Tennessee since 2011. The Mets did draft McWilliams’s younger brother, Ian, an infielder, in the 30th round in 2017. (Ian did not sign and attends Alabama Birmingham.)

“But no crazy connection, no,” McWilliams says.

One of Alderson’s early goals running the Mets’ baseball operations was to empower his pro scouts with greater latitude, rather than relying on a top-down hierarchy. Alderson was not familiar with McWilliams.

“It was the pro scouting staff that identified him and thought he was a guy who could help us,” Alderson says.

Alderson quickly learned that about half the teams in baseball had inquired about signing McWilliams. “Something like that,” McWilliams says when asked about the number of suitors. “I didn’t sit down and add them all up.”

Alderson viewed the bidding war as a form of crowd-sourcing: If so many teams were on McWilliams, he figured, the Mets were fishing in the right waters. One of the strongest bidders was a data-smart team that stood to lose several free agent relievers—another signal to Alderson that the Mets were on to something.

Says McWilliams, “I think once we started getting offers from a few different teams, we started out with one or two big league deals on the table. So those became the clear-cut choices.”

The Mets were one of the teams to offer a major league deal. To separate his bid, Alderson boosted the guaranteed money to $750,000, an unheard-of amount for a minor league free agent with no major league experience. The Mets gave Alonso $652,521 for 2020, the most ever for a player after his rookie season, breaking the record set by the Cubs and Kris Bryant ($652,000). The Mets offered McWilliams more than that after he pitched all season at 10 a.m. in an empty ballpark in Port Charlotte. They went the extra mile to acquire their first player under Cohen’s ownership, a signal to the rest of baseball of their willingness to spend. On Nov. 20, McWilliams agreed to the deal.

“They made a really good offer,” McWilliams says. “I really appreciate them reaching out and making me feel this was the right opportunity.”

McWilliams has made 94 of his 109 pro appearances as a starting pitcher. With his improved four-seam fastball and slider combination, he profiles more as a relief pitcher.

“We haven’t had that conversation yet,” he says of the Mets’ plans for him. “As far as I know it will be in the bullpen.”

***

In 2019, the Rays traded for a largely unknown 6-foot-6, 25-year-old right-handed pitcher with a 9.35 ERA in eight major league games for Texas. That was Fairbanks. This year Fairbanks struck out 13.2 batters per nine innings while throwing high-spin four-seam fastballs and sliders. He saved three of the Rays’ postseason wins, including the Game 7 pennant-clincher against Houston.

Pitchers like Fairbanks are changing baseball. The outs of a major league game are divided among more pitchers than ever before: 4.4 per team per game. The later a game gets, the more managers want pitchers who keep the ball out of play. The average relief pitcher today strikes out batters at a greater rate (9.4 per nine innings) than Verlander (9.0) or Sandy Koufax (9.2).

One out of every four plate appearances from the seventh through ninth innings is a strikeout. Almost 60% of those late-inning strikeouts result from four-seamers and sliders (59.1%)—up from about 50% in the first five innings (50.6%).

Technology is helping create those power pitchers, from high schoolers at Zombro’s academy to the stable of arms in the Tampa Bay organization. The steady inventory feeds the modern strategy of using more pitchers each game to keep the ball out of play.

The average four-seam fastball in the postseason this year was 95.0 mph, up from 94.0 in 2016. For the Rays this year, it was 96.7 mph.

Who is Sam McWilliams? The Mets think he could be the next Fairbanks. They were not alone. The bidding war to sign him is proof that the race is on to find such pitchers, even sight unseen. He is the proxy, not the anomaly, of what is going on in baseball.