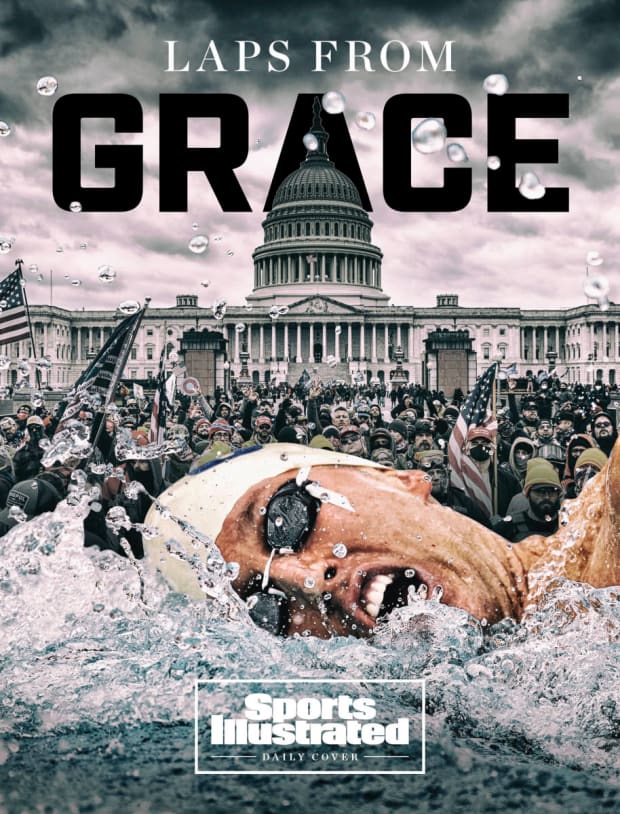

On Jan. 6 the American swimmer went from Olympic hero to FBI target for his role in the U.S. Capitol siege. What happened here?

In the fall of 1999, the top men’s swimming coaches in college rolled through the Phoenix home of Kelly and Karen Keller. They were making their final recruiting pitches to the Kellers’ son, Klete, a strapping, 6' 6" freestyle phenom.

But the visits were notably awkward. Jon Urbanchek, Michigan’s coach at the time, was in the Kellers’ home the night before national letter-of-intent signing day, and he’s never forgotten what Karen murmured to him. “Jon, you’re wasting your time,” he says she told him. “He’s never going to make it through college.” Urbanchek was taken aback.

“This was stunning, coming from his mom,” Urbanchek says. “It was like they were giving up on him. He had a rough time at home.”

Keller would sign with USC the following day, the next step in his rise through the swimming ranks. Ahead of him lay U.S. records and Olympic glory. Defying his mother’s prophecy, he would even earn a degree in L.A. But beyond that lay unending hardship and struggle. And still further beyond that: infamy.

On Jan. 6, Keller became the most recognizable invader of the U.S. Capitol. Towering above a crowd of domestic terrorists that made a deadly surge after listening to outgoing President Donald Trump, Keller all but flagged himself for authorities, wearing his Team USA Olympic jacket. If the Capitol was overrun by a mob that included some lost souls only loosely tethered to reality, well, it seemed Klete Keller had perhaps finally found his people.

The arrest eight days later of an American sporting hero turned American pariah triggered a sense of shock, but not necessarily surprise, within the swimming community. Keller is the product of what one person who knows the family terms a “strict, right-wing household.” And not a happy household at that. Most everyone in the tight-knit sport knows about Keller’s upbringing, and about the tortured path he took after retiring in 2008—in part because he talked so openly about it all. Says another source who has worked with many of the elite performers in the sport: “If there is one swimmer I could see being there, it’s him.”

“He’s been through a lot and doesn’t have a whole lot to lean on,” adds a former teammate. “There is no support system.”

More than a dozen of Keller’s old teammates, coaches and acquaintances all echo a similar portrait. Talented, affable, funny and troubled . . . with scars never fully healed from a dysfunctional home life. (None of the Kellers commented for this story, but Klete acknowledged in 2018 that his family “was not close.”) Sources familiar with the family believe that Klete hasn’t spoken to his parents since ’04, and that his three children have yet to meet Kelly and Karen. In recent years Klete has lived with his younger sister, Kalyn, another Olympic swimmer; and with his late grandmother; but he hasn’t gone home. The only comparable thing Keller ever had to father figures were his coaches: Pierre Lafontaine as a youth; Mark Schubert, Urbanchek and Dave Salo in college and as a pro. “His family life has not been great, and that was hard for him,” says Salo. “So many athletes strive for success to outpace their demons. If I only get this medal, everything else will be perfect. It doesn’t work out that way.”

Still. The U.S. is rife with people who experienced childhood trauma of some form, without ending up charged with a felony. And in many ways, Keller had it better than almost all of them. Everyone who stormed the U.S. Capitol broke the law, but those from other demographics are granted far less leniency than a white man in an Olympic jacket. There may be reasons Klete Keller’s life has gone off the rails, but there are no excuses. This is a sad story, not a sob story.

Video and photos from Jan. 6 do not show Keller engaging in any aggressive acts. If anything, he appeared to be an amused tagalong in D.C., carrying only a water bottle. “I know he’s not a violent individual,” says Salo, who coached Keller at USC in 2007 and ’08 (when he was a postgraduate), and who calls his old pupil “deeply patriotic.”

“I’d bet a lot of money he went to this rally thinking, This is going to be fun,” says Eli Bremer, a 2008 Olympic pentathlete and the former chairman of the El Paso County Republican Party in Colorado Springs, where he and Keller live. (Bremer says he is friends with and remains in contact with Keller.) “It probably never occurred to him that you can’t frickin’ go into the U.S. Capitol. That’s wrong. He’s going to face consequences for that, and he should.

“But he’s not the guy who said, I’m going to fly across the country and overthrow the government. You’re not dealing with a guy who’s thinking 10 steps ahead.”

Klete Keller’s ability to live in the moment and not think 10 steps ahead is one of the big reasons he found himself stepping onto an Olympic starting block in Athens in 2004, with thousands of fans howling and the weight of the swimming world on his broad shoulders. He was anchoring the U.S. men’s 4x200-meter freestyle relay, and while that quartet would be led off by the ascendant 19-year-old superstar of the sport, Michael Phelps, it was Keller who had the biggest job, tasked with holding off the greatest 200-meter freestyler on the planet at the time, Australian anchor Ian Thorpe.

The 4x200 relay was a match race for gold between the Americans and the Aussies. The U.S. looked to have more front-end speed with Phelps, Ryan Lochte and Peter Vanderkaay. But could Keller stand up to the challenge of the man nicknamed Thorpedo—an intimidating closer with size-17 feet, in a black, full-body racing suit?

“Klete was the guy you wanted anchoring a relay like that,” says Vanderkaay. “He never seemed to show nerves, was never going to let the moment dictate the strategy.”

Staked to a solid but hardly insurmountable lead, Keller presciently predicted the way the last leg would unfold: Thorpe would over-swim the first half, close the gap, but not have enough left to finish. Keller never let Thorpe pass him, although it got close in the final 15 meters. Ultimately, Keller’s long reach got him to the wall 0.13 seconds ahead for the gold, cementing his place as “the guy who touched out the world-record holder . . . an American hero,” says Vanderkaay. Phelps’s resultant guttural scream of celebration was memorable, and his was the first hand to reach down and congratulate the exhausted, ebullient anchor. It was the crowning achievement in Keller’s occasionally tempestuous tenure training and competing alongside the U.S. legend. Everything after that would be an anticlimax.

After two seasons at USC, Keller had turned pro and migrated in 2002 to the Michigan campus to work with Urbanchek and Phelps’s coach, Bob Bowman. That Club Wolverine training group was the best in the world, and arguably the best in the history of the sport. Keller had the ability and, once he was in the water, the mentality to hang with everyone. He had beautiful technique and trained hard. But while Bowman was hyperfocused and Phelps was closely attuned to his mentor, Keller’s practice approach was different. “Klete was loosey-goosey,” says one member of that training group. “He wasn’t always in the water right on time.”

Keller had a knack for cracking jokes or pulling pranks that could cut the tension at big meets. “He made people laugh, and they enjoyed being around him,” says Lindsay Mintenko, a former teammate of Keller’s and the current national team managing director of USA Swimming. But he was also a bit of a needler, which didn’t go over well with Phelps. During one brief stretch, Keller, a freestyle specialist, suddenly developed a fast breaststroke and started to beat the rest of the group, including Phelps. Then Keller ran his mouth about it. “Michael could be easily agitated by someone like Klete,” says an observer from that period. (Phelps, an outspoken mental health advocate of late, who hasn’t spoken publicly about Keller’s downfall, did not return an interview request. Bowman declined to comment.)

Keller has admitted in the past that it was a mistake to keep swimming following the highs of Athens. Across the 2000 and ’04 Games he’d already accrued a gold, silver and two bronze medals. Training for mid-distance freestyle was an unforgiving grind, and four more years was a big commitment.

After a break, Keller showed up the next season having gained so much weight that he was hard to recognize, and this wasn’t a welcome look at Club Wolverine. Phelps was setting his sights on a record eight golds in 2008. Urbanchek had retired, and Bowman was going to ratchet up the intensity. Keller persevered for a couple of years, but following a disappointing performance at the ’07 World Championships, he and Bowman decided it was time to part ways.

Bowman recounted a story a few years ago at a coaches’ convention about “breathing fire” at his swimmers one day during that period. The way he told it, he wrote the phone numbers of three elite coaches on his office window, including Salo at USC.

“When you’re in my pool, you’ll do it my way—and if you don’t like it, you can call any of those guys and go do it their way,” Bowman recalled at the convention. “Well, Klete called Salo and moved to USC.”

Keller still had enough drive and talent to make the 2008 Olympic team, but only as a relay alternate. He swam a leg in the preliminary heats of the 800 free relay, earning one more gold, and he was done.

All athletes are susceptible to struggling after the cheering stops. For Olympians, the challenges can be even more daunting. “It’s a massive transition,” says Natalie Coughlin, who swam with Keller at the 2004 and ’08 Olympics (and without him in ’12). “USA Swimming and the [U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee] tries to help you, but when you try to . . . win a gold medal, it is all-consuming. You cannot be thinking about something else. You cannot have a safety net. Allowing that safety net takes the focus away.”

In addition to de- and reconstructing a lifestyle that revolves around massive training demands, most of those athletes don’t walk away with a financial reservoir that allows for easing into a second career. Unless your name is Michael Phelps or Katie Ledecky, most elite swimmers quickly need a job to pay the bills that keep coming after the medals stop.

And “sometimes that transition comes on us quicker than we’d like,” says three-time Olympian Brendan Hansen, now the director of teams services for USA Swimming.

With no safety net, Keller landed hard.

In 2018, on a podcast hosted by the Olympic Channel, Keller described his post-swimming malaise in stark terms: “I lost several jobs. I wasn’t a good employee or worker for the longest time because I expected it to come to me as easily as swimming did. When it didn’t, I would get upset. . . . I would try really hard for three months and pour every ounce of myself into that job, and then once things started going south or didn’t pan out the way I expected them to, I lost that enthusiasm. . . . I was like, ‘This job sucks. It’s not fulfilling. I’m not going to get anything out of it. I’ve been an Olympian, and this doesn’t mean anything to me, anyway.’

“I was really cocky and expected to perform the way I did in swimming all the time. . . . On top of the work being unfulfilling compared to swimming at the Olympics, I had an entitled attitude. . . . I expected to win, I expected people to respond positively to me, and when that didn’t happen over and over and over, it really affected my general outlook on life. I got really down and bummed out about everything. . . . I gained a ton of weight because I would eat and drink beers at night out of frustration. . . . Everything started spiraling out of control. . . . I became a real lazy, spoiled,

entitled person.”

Keller told the story, too, of coming home in January 2014 to find a letter from his wife, essentially ending their marriage and kicking him out of their house in Charlotte. The next day, he lost his job. Soon he was living out of his Ford Fusion, sleeping in Walmart parking lots.

“I used to kind of look down on people that [didn’t] have it all together,” Keller said. “All of a sudden, I was one of those people.”

Keller moved in with his sister Kalyn, in Washington, D.C., giving him a stable place where he could begin to piece things back together, including his relationship with his children. In late 2016, Kalyn and her family moved to Colorado Springs, and in ’17 so did Klete.

Elite swimmers tend not to have the warmest feelings about that city, host of the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Training Center, where many club teams go for weeks of grueling altitude training. For them, Colorado Springs is synonymous with pain. But for Keller, it offered a chance to stop his personal tailspin.

Keller took on several real estate jobs, leveraging his relative fame—his work website was theolympicagent.com—and moved into his own home. In the summer of 2018 he started popping up in the media, telling his story, framing himself as someone who’d suffered a series of hard knocks and gotten back on his feet. (A year into his Colorado stay he also relayed a bizarre story about a dog sitter who used his house, without permission, for rather unusual purposes.)

During this rebuild, Keller deepened his friendship with Bremer, the Republican Party official. The two would play golf at Colorado Springs Country Club, then sit on Bremer’s balcony overlooking the seventh hole, tipping back beers. Keller had taken to professing pro-Trump views on social media (all of which has since been deleted); Bremer worked on Trump’s election campaign and has been active in trying to fund support for Olympians during and after their careers. The two men had common ground in a state that is increasingly turning progressive, and that as a whole went handily to Joe Biden in November. El Paso County, an old Republican stronghold with large military and conservative Christian populations that went handily to Trump, has some conservative extremists and militia members—but Bremer insists that neither he nor Keller have anything to do with them. “We have radical right-wing politics in Colorado Springs,” he says. But “they would never give Klete the time of day; that’s not who he is. He’s sort of libertarianish—let people do their thing. I don’t think his political beliefs run too much deeper than that.”

Bremer was intrigued enough by Keller’s mix of ideology and name recognition, though, that at one point he asked whether his friend would ever consider running for office. (Bremer, the former pentathlete, has a theory that Olympic athletes and politics go together well: Like the Games, elections occur every four years; there’s massive preparation and extreme intensity, culminating in a defined winner and loser; and the winners could be immortalized forever.) Keller was moderately receptive, but when Bremer asked Keller whether he was a registered Republican, the old swimmer said he didn’t even know.

Bremer says he tried to get Keller into a Trump event in Colorado at one point, but he couldn’t pull it off. He says that, before the Capitol storming, Keller made one other trip to D.C. for a Trump rally. He thinks the excitement of that visit spurred him to return in January. “He’s a goofball; he thought it would be fun,” says Bremer. “And it was the last chance for four years to see a president he liked.

“He did not go to the Capitol because he’s some depressed Olympian who was pissed off at the world. No one cared about Klete for 12 years, until he did something stupid.”

Since Keller was arrested and charged with three felony counts (obstructing law enforcement; knowingly entering a restricted building; and violent entry and disorderly conduct on Capitol grounds) he has remained in contact with Salo and Urbanchek, his old coaches, who have offered support. Keller, out on bail, has apologized to them multiple times, they say.

Urbanchek reports that before the Capitol fiasco, Keller was engaged to remarry, and his fiancé is sticking with him. He believes Keller has lined up new employment after being fired from his latest real estate job. “He’s doing a lot better than a couple weeks ago,” Urbanchek says. “He was very embarrassed, felt he let everyone down.”

As news of that letdown spread among old teammates, across text messages (outpacing even the news reports), past acquaintances found themselves appalled, of course, but also curious about Keller’s motivations. Many of them think he believed he was doing something heroic for America—perhaps, they think, that’s why he wore his Team USA jacket. A guy who once stood on the top step of a medals podium with his hand on his heart, singing the national anthem, might have thought this was his most patriotic moment since holding off Ian Thorpe for Olympic gold.

Instead, he may be going to prison—for as long as 15 years—for participating in sedition. The very opposite of patriotism.

This, says Hansen, “was one of those situations where you see a teammate who is lost. It was really sad.”