Mark Few built a major program at a small school but has yet to win the big one. Could his current squad be the one that does it?

Maybe last year was the year, the culmination of 22 seasons, the March when the Gonzaga men’s basketball team would complete the final step in its remarkable transformation. Gone were the Cinderella upstart years, the happy-to-make-the–NCAA tournament years, the not-again-early-upsets years. The 2019–20 Zags were a national power missing only a national title, and they had built out a résumé befitting the No. 1 overall seed. With Spokane slated to be a tournament site, that should have meant home games with sold-out crowds, everyone breathing and screaming and pushing the Bulldogs to upend their history, to tear off the always-good, sometimes-great, not-yet-champions tag that all but hangs above their jersey numbers.

Coach Mark Few liked his chances. Smooth, versatile big Killian Tillie seemed to have recovered from the stress fracture in his left ankle and then the knee problem that had hounded him for a season and a half. The field appeared wide open, perhaps more than usual. Gonzaga could score, shoot, pass; it had depth, experience, stars, a surefire Hall of Fame coach, an international pipeline, a performance staff that focused on mental health. The Bulldogs had everything they needed—until none of that mattered.

On that March day when COVID-19 canceled the NCAA tournament and ended Gonzaga’s title push, Few called everyone in for a team meeting. He told them they had outperformed his expectations, like “no team we’ve ever had.” He looked at the two graduate transfers, who had come to the small, private, Catholic university in eastern Washington to win it all. He glanced at Tillie, the Frenchman, a pillar, only 21 and yet so resilient. Few paused. He didn’t know what to say. Nothing seemed appropriate. Devastating, he says now.

“We knew it was the last time we would be in the same room together,” guard Joel Ayayi says.

Eventually, Few resumed a speech he calls “awful” and “probably one of the worst, if not the worst, moments we’ve had” since his arrival in 1989. He reminded the group that the pandemic stretched far beyond basketball, that lives were being lost, that the big picture presented sacrifices far larger than theirs. And yet, the sentiment in some ways sounded hollow, even as the words spilled forth. They had sacrificed, had “put their heart and soul and whole life” into the very thing now gone. All those sentiments could be true. Few could hate what happened to his players, lament the missed opportunity and realize that it was necessary. There would be more chances for the basketball power in Spokane, which spoke to the unprecedented program he’d built, a college basketball force in the last place anyone expected.

At every previous season’s conclusion, Few had trained his focus on growth, process, evolution—all program hallmarks. But a different question lingered that day, and has in the year since. Now what?

Deep into the next season, in a world that still resembles an alternate universe, Gonzaga now appears closer to the year than ever before. Maybe. Few’s not exactly sure, or he won’t exactly say. His Bulldogs already boast victories over Iowa (ranked third at the time in the AP Top 25), Kansas (sixth), West Virginia (11th) and Virginia (16th). Through 19 undefeated games, they’re averaging 92.7 points and winning by 23 on average. Having emerged from their loaded nonconference gantlet unscathed, as of press time there’s no reason—beyond an off night, a devastating injury or some sort of cosmic event—to believe they won’t finish the regular season undefeated, marking another first for a program that long ago began collecting them.

Among the milestones: first tournament win (1999), first Elite 8 (same), first first-round stumble (2002), first No. 1 ranking (’13), first No. 1 seed (’13, too), first title game reached (’17). “I’m always amazed at how we think they’ve reached the ceiling,” says Dan Monson, the Long Beach State coach who is Few’s predecessor, friend and former boss. “But there does not seem to be one, and that’s the most amazing thing about it. Look at Duke, North Carolina; over the last 20 years, they’ve all had an ebb and flow. [Gonzaga] just continues to climb.”

Even this season, amid the pandemic. These Zags became the first team in the history of college basketball to knock off four opponents then ranked in the top 20 in their first seven games. Their odds to win the national title dropped almost in half, from +450 to +275. Then the comparisons started, first to other Gonzaga teams (the great-but-not-confetti great), then to the 1975–76 Hoosiers, college basketball’s last undefeated national champion. All of which pointed Few down his least favorite road, the one that traces his program’s long, debated and endlessly shaped and reshaped history—the one that always ends with some theory or another for why that biggest first has long eluded Gonzaga.

“It seems like we’ve been dealing with this for a while,” Few says. “Look, we all know—you, me, everybody; fair or unfair—we’re going to be judged by March.”

The most annoying question anyone can ask Few is whether this marks his best team, which is exactly what I did (whoops). Last season would have marked the Zags’ 22nd-straight NCAA appearance, meaning there are many “best” teams for Few to choose since taking over in ’99. “It’s just not fair and way too early,” he says, fairly, over the phone in late January.

He then begins comparing to shoot down the need for comparisons. The 2016–17 group came within 30 seconds of winning that elusive title. The ’18–19 squad stood “a couple bad minutes against Texas Tech” from returning to the Final Four. Few disdains this exercise in general, laughing at how the last two teams to win the College Football Playoff were quickly proclaimed the sport’s greatest champion. “Really? In back-to-back years?”

Every team, every season, they’re all different, he says. His son Joe, a high school senior, likes to watch old games in the family basement and recently stumbled upon the 2017 Final Four. That Gonzaga team featured towering big men who plodded, blocked shots and played ironclad defense. This year’s team is pretty much the opposite, the offense loose and creative and efficient, the leading rebounder Ayayi, a 6' 5" guard.

What differentiates this particular team also marks the latest step in Gonzaga’s evolution. Namely, Jalen Suggs, whose mere presence marks a recruiting coup beyond any player Few has previously landed. The 6' 4" combo guard drew interest from college football powers after a dominant high school career as a dual-threat quarterback and shutdown corner. Ohio State, Minnesota and Iowa State all offered football scholarships, believing Suggs should play in the NFL. (Suggs says he liked Ryan Day and likely would have chosen the Buckeyes if not for a heartfelt sit-down with his father that pushed him toward basketball.) Most hoops powers also tripped trying to hand him scholarships. But Suggs chose Gonzaga, where he has defended 7' 3" centers, set the offense, blended into the roster and amped up the buzz that he could be taken first in the next NBA draft.

Pivoting with Few into friendlier territory: Do the comparisons stem from trying to explain something he created that lacks a clear precedent? The line goes silent, briefly. Maybe? But it’s more than that, he says. It’s not like he can snap his fingers and win a basketball game, not like there aren’t blown calls (like in Virginia’s 2019 title run) and last-second miracles (Kris Jenkins’s buzzer beater for Villanova against Carolina in ’16) that decide national champions, narratives and legacies. March is, by definition, mad.

Others do not share Few’s reticence for comparisons. Not when a member of the original ’99 Cinderella team, forward Casey Calvary, calls Few a “maestro” and says he’s never seen a team like this one, the squad that Few has fully modernized to play an open, free-flowing style that looks as much like the NBA as college basketball. “All the things that Gonzaga is doing now we’ve always done; they’re just amped up,” Calvary says. “I will tell you this is the best Gonzaga basketball team I’ve ever watched play in my life.”

Does that mean this is finally the year?

“Come on,” Few says.

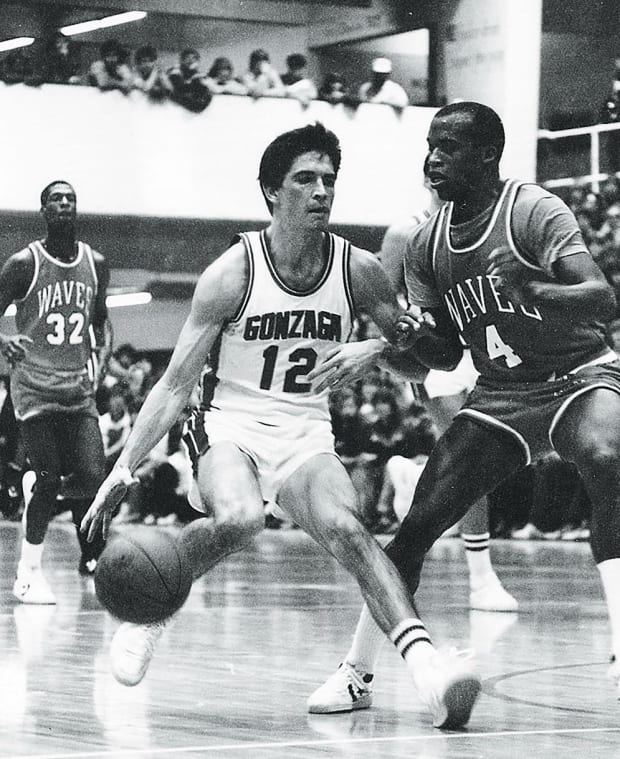

For Mike Roth, Gonzaga’s longtime and mustachioed athletic director, the current program, with its chartered flights, palatial training center and millions in TV and sneaker revenue, doesn’t even vaguely resemble earlier versions. He would know. In 1982–83, he latched on as an assistant coach. That team would finish 13–14, despite the presence of a future NBA Hall of Famer. “John Stockton,” Roth says, laughing. “But we weren’t drawing attention.”

They shared the same gym with women’s hoopers, the volleyball teams, intramural leagues and physical education classes. They never played on national TV. Even the 1998–99 team, coached by Monson, featuring Calvary and Matt Santangelo, had no idea the bountiful future ahead. There was Gus Johnson, screaming, “The slipper still fits!” as the Bulldogs toppled Florida in the Sweet 16. Gonzaga didn’t even have a band! They had to rent one for the run. Merchandise seekers were told, “Come to our bookstore. We have three shirts and one hat!”

Since then, the evolution of Gonzaga has unfolded in three phases:

Phase 1. Growth. And a program can’t grow without nurturing, which Gonzaga discovered when Minnesota whisked Monson away on a private plane, hiring him after that Cinderella season, highlighting the resources big-time college hoops required. Roth told the then university president, Father Robert Spitzer, that he planned to hire Few, the son of a pastor from small-town Oregon, an avid fisherman and respected assistant who had spent the previous decade on Gonzaga’s bench. “Which one is he?” Spitzer asked.

In Few’s first season, the Zags added a strength coach, a self-described “football meathead” named Mike Chrysler. Most Bulldogs didn’t know what “strength coach” meant. This was a program, after all, where players wore the same pair of sneakers until holes formed. Chrysler rigged a harness to his white Toyota Tacoma pickup so Zags could pull the vehicle down the street, adding teammates to the cab for more weight.

Few almost forfeited his first game as coach when the bus the team chartered nearly slid off Lookout Pass en route to Montana. The Bulldogs won, but victory wasn’t exactly a harbinger, not even to those involved. “Did I think Mark would be this successful?” Roth asks. “Heck no.”

Then, as Few built on what he inherited, came the trophies, the love, the major program in the mid-major city, the new arena, the expensive tickets. Other coaches began to visit Spokane, trying to figure out what Few had done. Then business leaders started dropping by. CEOs. Authors. University presidents. The Zags had become, Santangelo says, “everyone’s second-favorite team.”

Phase 2 started around then, when success became routine but perpetual national prominence—the Duke-Kentucky-UNC kind—remained out of reach. Gonzaga expected to make the tournament every year, but simply getting there no longer held the same significance. “Just” winning the West Coast Conference became more of a letdown. “Down” years meant taking that crown and losing early in the tournament that mattered. Even with more elite recruits, from 2002 to ’08, the Bulldogs stumbled in the first two rounds in all but one tournament.

The low point: 2013. Southern nearly made Gonzaga the first No. 1 seed to fall in an opener, and, even after surviving, the Bulldogs bowed out to a program vying to become the new Gonzaga, Wichita State, again failing to advance to the tournament’s second week. In Salt Lake City that first weekend, the crowd saw the OG Cinderella and . . . booed. The Zags, it seemed, had won too often (in the regular season, stoking hatred) and too little (when it mattered, bolstering scorn). “We’re actually in Stockton’s building, and the whole crowd turns on Gonzaga,” Santangelo says. “First time I’d ever seen it.”

Keep growing, Few told his staff. Concentrate on culture. Focus on how the players fit together. Chemistry became a focus. That directive fell, in part, to Travis Knight, the program’s performance guru (not to be confused with Travis Knight, the former UConn star and NBA center). With physically stronger players, Few needed mentally stronger ones—and not just individually but as a group. “I don’t know that we knew how to handle [everything well],” Knight says. “It felt like we were kind of losing our edge.”

The Bulldogs took offseason bonding retreats and toiled in escape rooms, anything to fortify their bonds. The emphasis paid off in 2014–15 and subsequent seasons, as Gonzaga has advanced to the Sweet 16 in every tournament since. Top West Coast recruits came to see the Zags as the best program west of the Mississippi, and that led to even better players—but ones who fit the new emphasis, which led to fewer transfers and only rare one-and-done signings. The difference, Calvary says, between a perennially top-25 team and a perennially top-five one.

By the time the Zags reached the ’17 title game, Santangelo says, “Everyone kind of fell back in love with them.” Phase 3 had commenced, as the program’s blood turned bluer and the aspirations approached title or bust. Gonzaga had evolved beyond a blueprint for other mid-major programs, into something greater, less replicable.

I asked Few, Roth and Gonzaga legend turned broadcaster Adam Morrison whether the Zags were more like Notre Dame football, an entity without logical precedent, a big thing in a small place that sustained relevance far longer than anyone could reasonably have expected. No one disagreed. Fans can now buy Gonzaga gear all over the world, even in Japan. They make pilgrimages to Spokane. Roth points to upticks in enrollment, the test averages of incoming students and the number of high-level academics seeking employment. The basketball team, he notes, “changed the academic profile of the university and raised it to the level of a national institution”—not unlike the football power birthed in Indiana. “I only knew Gonzaga as one of the top programs in the country,” Ayayi says, and he learned that while growing up in France.

The flip side of that new status lands on program icons like Morrison. Now broadcasting near the bench, he says sometimes players know him simply as the radio guy, rather than the former national co–Player of the Year who played five NBA seasons. When a few top recruits didn’t make the connection, Morrison says Tillie told them, “You know, his jersey is in the rafters.”

That’s how far the evolution went. And all the hallmarks—adaptability, flexibility, culture, chemistry—would become even more important now, in 2020–21, the “accumulation of decades of this program continuing to refine what we do,” Knight says. Players like Ayayi waited out the pandemic in Spokane, across the ocean from family members, which impacted their mental health.

Knight couldn’t use retreats, yoga or escape rooms. He needed deeper connections that could be made virtually. So he emphasized Personal Growth Monday, meeting

with players for 15 minutes without any coaches present. He showed video clips, like one of Bucks forward Giannis Antetokounmpo from a few years ago grinding away in a small market while living in a one-bedroom apartment (the takeaway: not unlike them). Or how Jalen Hurts gracefully handled losing the Alabama quarterback job to Tua Tagovailoa (the ideal locker room dynamic). Sometimes, he brought in guest speakers, like after Kobe Bryant died, when Morrison and Robert Sacre (both ex-Lakers teammates) gave speeches that left the Bulldogs in tears. “I didn’t want to leave the room,” Ayayi says, “because it felt like we were keeping Kobe alive.”

The meetings helped stabilize a team adrift, like everyone, in an unstable world. “It allows you to grow in a short period of time, like bamboo,” Knight says. “And when it’s really chaotic and windy and crazy, that foundation allows you to not be thrown by the circumstances or chaos.”

Like when Santa Clara officials postponed a game scheduled for early January and the Zags penciled in BYU on three days’ notice and won by 17. Or when players needed to separate from friends and family, play in empty arenas, take online classes, wear masks in meetings and eat their meals 10 feet apart. Every program went through this. But Gonzaga was as prepared as anyone, by the resiliency baked into the evolution.

The thought process became, Knight says, “They’re just going to show up, trust in what we’re doing and treat it as normal as we can.” Basketball courts would become their new escape rooms, and while the Zags dominated, other long-established programs like Duke, Kentucky, Syracuse and UNC all struggled. Morrison does not see that as coincidental. “If you don’t have four-year players, or three-year players, it can be difficult to come through a situation like this,” he says.

The Bulldogs didn’t need to say that; their record did.

How then to explain the this-is-the-year Zags? Why this team, over all the others? Start with senior Corey Kispert, the classic Gonzaga pillar who developed

year by year and averages about 20 points per game, headband flopping all over, while distributing and rebounding and working toward national Player of the Year consideration. Then there’s Drew Timme, the 6' 10" sophomore who ranks among the best passers on a team averaging 19.3 assists through 19 games, third best in the nation. Plus, junior Andrew Nembhard, the stabilizing point guard who transferred from Florida.

There’s more. Ayayi long ago transformed from a skinny recruit who Few doubted could play for him into the player who registered the program’s first triple double—another historic mark. “Our motor,” Suggs calls him. Local forward Anton Watson provides valuable minutes—he was raised in Spokane, unlike his teammates from France, Canada, Mali, Lithuania and Russia, the latest proof that the Zags have long excelled at recruiting top overseas players. That’s always been Gonzaga: the homegrown, and the developed, and the international. Just now, with guys like Suggs.

That foundation, built in large part by developing upperclassmen, has helped the team absorb his supernova talent without disrupting its hard-won chemistry. Certainly, Few and ace assistant Tommy Lloyd have netted their share of stars over two decades. But even Morrison, who went third in the 2006 NBA draft, describes a player of Suggs’s caliber as a level beyond all of them. Told this, Suggs says, “I agree.” Over beers recently in Few’s office, Morrison suggested an NBA comp: Bradley Beal, the Wizards’ All-Star swingman. More important, “[Suggs is] here for a year. He’s gonna go pro, but he picked Gonzaga to help him make that transition,” Calvary says.

These Zags are multidimensional, less slotted for specific roles. The way they play reminds Knight of a jazz ensemble. There are set concepts, sure, but there’s an important improvisation born from the performance work, the varied skill sets and the established familiarity.

Which leads back to Morrison, still Gonzaga’s single-season points scored record holder. Sometimes, he becomes lost in one riff or another, wishing he could play again. He says that Few has relaxed restrictions on how often players can shoot and from where. He also says Few and Lloyd are better coaches than they were during his tenure—and he doesn’t say that to slight their coaching of his squads. They now run an NBA-style offense that features cutters, high-ball screens, fast tempo, floor spacing and decisions based on reads, which Suggs points to as a major factor in his decision to play there. On nights off, Morrison sometimes watches other games, so many 58–55 scores and inept offenses that make him “want to stab my eyes out.”

“This program is on a different level,” he says, “as far as style of play and efficiency, and it’s not even close. It’s a lot like the NBA.” Plus: “It’s not like we didn’t have good players. But now they’re getting dudes. [Suggs] can run a program and an offense with other good players around him, just like in the league.”

The latest steps only heighten the typical cycle at Gonzaga, with the friendlier style leading to more NBA-bound recruits. The Zags rank among the favorites to land Chet Holmgren, the nation’s No. 1 prospect (and Suggs’s high school teammate).

Don’t jinx it, they say. Don’t ruin the run. This year? The year? Hard stop. Still, they all believe that, even if there are lingering concerns, like a good-but-not-great defense and a short rotation that, during the regular season, has left talented players rusting on the bench. But those are minor worries relative to the Zags’ now-even-more-considerable strengths. The program has worked hard to move past its old rep as a mom-and-pop operation, Monson says. Now “they’re really running Amazon.”

So . . . is this Few’s best team? Monson says it will be. Santangelo says it’s the most dynamic and versatile. Nembhard says “it’s about time” to win that title. Few? Stop projecting, he says. Stop saying that a November win doesn’t mean much to Gonzaga, when each victory does mean a lot to him. Stop trying to define the Bulldogs in ways they never defined themselves. “I mean, I appreciate it,” he says, meaning the success, the interest and the evolution, the force that Gonzaga basketball has become.

“I count my blessings for this every day,” Few says. “For this job and this place and, probably more than that, for the people I get to coach. I don’t take it for granted. I’ve [always] tried to take that stance, but it falls on deaf ears.”

Santangelo sometimes jokes that the marketing department uses some version of the best-ever-Bulldogs slogan every year. When it finally rings true—this year, next year, later—he believes the narrative will shift again. He wonders if outsiders won’t react how many did when Phil Mickelson won his first golf major, the discourse shifting from the one thing he hadn’t won to all the stuff he had, leading to an appreciation for his longevity, year after year of success that proves Few’s point. Wasn’t Mickelson the same golfer after his first major? Shouldn’t the lens be longer, less narrowly focused?

A title won’t define the Zags, says Roth, the mustachioed athletic director. Confetti won’t equal a culmination. Instead, he sees another step, the largest one. And, if any year is going to be the year, they all know: This is as good a year as any.