As Astros-hate—and all the other pain of 2020—wore on him last season, his play suffered, his throws sailed and he says the game stopped being fun.

After every errant throw on a baseball field, there comes a moment, once you have failed to point your front shoulder at your target or misplaced your four-seam grip or neglected to open your hips, when you realize you are doomed. All that is left for you is one excruciating thought.

“You’re just hoping something crazy happens and you make an out,” says Jose Altuve.

Then ball collides with dirt and hope collides with reality. Again and again last October, reality left Altuve shaking his head in frustration as his teammates chased after throws he bounced in front of them or sailed beyond them. In the cavernous, empty Petco Park where the Astros and the Rays played for a pennant amid a pandemic, it seemed as if every person in the stadium winced whenever a groundball headed toward Altuve’s glove.

Here he was, 30 years old, a former MVP and Gold Glove winner, and well into building his Hall of Fame case. Now he couldn't make the shortest throw in the sport.

People close to Altuve believe that a year marred by isolation, loss and scandal left him wounded, short-circuiting the connection between his mind and right arm. He says he does not want to make excuses. He acknowledges only that 2020 was “hard for everyone.” In any case, the season ended in despair, as his poor throws changed the complexion of two ALCS games Tampa eventually won; Houston lost the series in seven.

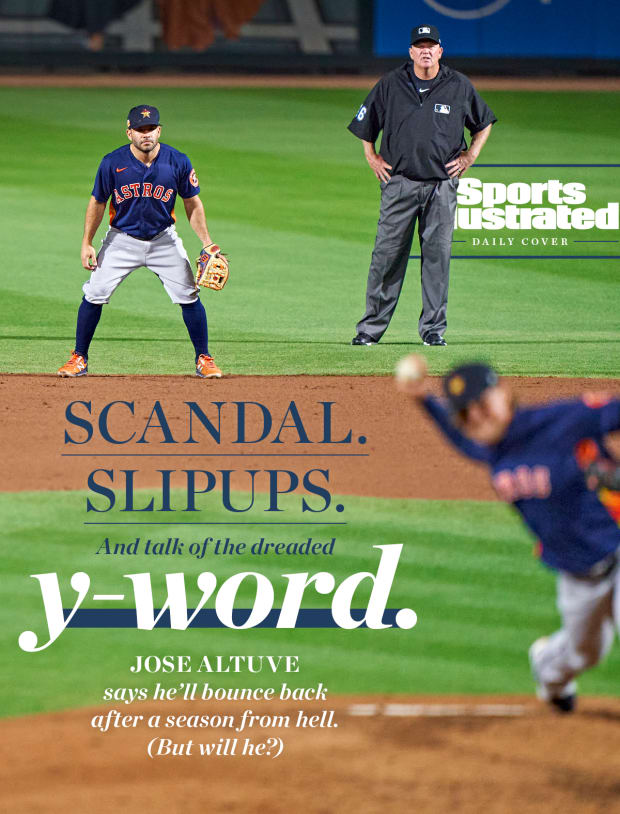

Five months later, Altuve and the Astros insist he did not have the yips, that most dreaded of baseball diseases: an inexplicable inability to make routine throws. But as the 2021 season begins, they must answer the most pressing question facing the most despised team in baseball: Can their second baseman play second base?

Altuve's throwing problems appeared to come out of nowhere. They were more likely a culmination of a variety of issues—and while they shocked fans, they did not completely shock the Astros.

Weeks before Altuve’s arm became the hottest topic in the sport, he helped cost his team a late-September game against the Rangers. With one out and runners on second and third in the bottom of the 10th, Houston’s infielders crept toward the pitcher’s mound, hoping for a grounder and a play at the plate. They got one. Altuve gloved the ball, then fired it—wide of home on the first base side. The run scored. The Astros lost.

The loss slid Houston back to .500, 6 ½ games out of first place in the American League West. In the wake of the revelation that the 2017 Astros had illegally stolen signs en route to a title, the beleaguered team scuffled all season and nearly missed the ’20 playoffs entirely.

Most of the industry might not have noticed Altuve’s gaffe. But officials in Houston did. And many of them were not surprised.

Even as Altuve was winning the AL MVP award at second base in 2017, the Astros were thinking of moving him off the position, according to three people familiar with the discussions. Altuve had won a Gold Glove there two years earlier, but newly available Statcast data now indicated that he struggled moving laterally—that he was, in fact, the worst second baseman in the game at going to his left. But he excelled at coming in on balls and he had good speed. Then GM Jeff Luhnow’s front office discussed moving him to centerfield. Utilityman Marwin González would handle second, centerfielder George Springer would shift to right and rightfielder Josh Reddick would lose playing time. They came close enough that Reddick showed up to the following spring training with a first baseman’s glove. Eventually the coaching staff convinced Luhnow that demoting the unofficial team captain would upset the rest of the players, and Luhnow shelved the plan. (Luhnow did not respond to a request for comment.)

Those conversations continued on and off for the next two years, in part because of the way Houston deployed its personnel. Since 2016, when Statcast began tracking such things, no other team has employed a defensive shift as often as the Astros, who used one in nearly half of plate appearances in ’19 and ’20. The reshuffling asks a great deal of all infielders, but perhaps no one is more affected than the second baseman. Altuve plays second because he lacks the arm strength to play shortstop. Yet when the team shifts against righties, there is Altuve, trotting over to the third base side of second base; when it shifts against lefties, he is stationed in medium-depth rightfield.

He never felt entirely comfortable making throws from a shifted position, according to two people who know him well. But the Astros saw his anxiety as unfounded and believed it could be overcome. The best way to conquer a fear of flying is to keep boarding planes. They wanted their second baseman playing at shortstop against righties and in short right against lefties. So they framed the request as, We need you to do this for the team, and Altuve complied. Still, opposing scouts included the weakness in their reports: In a big spot, they told their hitters, challenge his arm.

So when Altuve made that errant throw against Texas, some saw an aberration. But others saw a harbinger.

Ever since he debuted at 21 in 2011, Altuve had been a source of delight among fans. At 5' 6" and with a smile almost as wide, he looks more like a batboy than a ballplayer—until he lashes a ball into the gap. His origin story became the stuff of legend: He had been turned away from a tryout as a Venezuelan teenager because Astros officials doubted he was as old as he said; he returned the next day with his birth certificate and sprayed line drives around the field.

In the majors, he wore his socks to his knees and had to jump to reach his teammates’ high fives. When 6' 7" Yankees rightfielder Aaron Judge made it to second base against the Astros in the 2017 ALCS, the resulting photo all but crashed Twitter; Packers tight end Jimmy Graham and assistant athletic trainer Nate Weir re-created it for Halloween. Fans created a new measurement of distance, the Altuve; a website offers a calculator to help with conversions. He won the fan ballot to start the All-Star Game at second base every year from 2015 through 2018; in ’18 he led all players in votes with 4.8 million. He was “everything that’s right” about the game, says his former manager A.J. Hinch. Altuve embodied every undersized athlete’s secret belief that they, too, could have made it. Everyone, it seemed, loved him.

Now everyone hated him. The rest of the Astros insist that Altuve did not approve of the team’s sign-stealing scheme nor use any stolen signals in his at bats (the findings of one Houston fan who tracked the data corroborates that). But after the story broke in November 2019, Altuve declined to defend himself publicly, which was understandable: He risked alienating his teammates if he said he was innocent but they were guilty. Public opinion probably would not have changed, anyway. He surely benefited from the cheating, after all; he scored 112 runs that year, the second-most in the AL, in part because the teammates who drove him in often knew what to expect. And he won a ring.

In any case, he was the face of the Astros, so he became the face of the scandal. When his walk-off homer sent the Astros to the World Series a month earlier, he had fended off teammates who attempted to rip off his jersey; he said afterward that he was “too shy,” but internet sleuths cited the moment as evidence that he had been wearing a buzzer that signaled which pitch was coming. (Commissioner Rob Manfred has said the league found no indication that Houston wore buzzers.)

His teammates seethed as fans and opponents excoriated him. “He is the one guy that actually was against all that,” shortstop Carlos Correa says now. “He’s the one guy that didn’t do any of that. And he’s getting all the—whatever people say. He was the one guy that would get mad at people for it. He was the one guy that didn’t want any part of it. And that can be tough, if you’re him, knowing that you are the one guy that didn’t do it, but you don’t want to throw your team under the bus, so you stay quiet.”

Then the team chose Altuve and Alex Bregman—two of its most prominent hitters—to deliver brief remarks after owner Jim Crane’s press conference to open its 2020 spring training camp. “The whole Astros organization and team feels bad about what happened in 2017,” Altuve said. He added that they were determined to “play with intensity” and “bring a championship back to Houston.”

“He was thrust into that situation where maybe he shouldn’t have been,” manager Dusty Baker says now. “He had to answer for the whole team, and he’s probably suffered for it more than most and had to hear about it undeservedly more than most.”

Once spring training games began, players found their walkup music drowned out by boos. They would hear children call to them and turn—only to realize the children had been sent by their parents to berate them. Even when the pandemic kept fans from the ballparks, some people gathered to jeer as the team bus rolled by.

“That crushed him,” says one person who knows Altuve well. “He’s a little bit of an introvert, so he doesn’t love the attention.”

When the abbreviated season began, he scuffled at the plate. After two weeks, he was hitting .177. He had weathered stretches like this before, but in 2020, two weeks was a quarter of the season.

Meanwhile he was suffering the loneliness and tragedy that so many people worldwide experienced in 2020. Baker said this spring that Altuve suffered “some deaths in his family,” and one person with the team says he could not leave to attend funeral services. Instead he went to work and thought about how little time he had to save his season. Some people close to him wondered if he should opt out.

Altuve says his family tragedy did not affect his play. But he admits the circumstances of the season wore on him. “This game,” he says, “is supposed to be fun.”

The lasting image of the Astros’ 2020 postseason run might be that of Altuve, brooding silently near second base for more than 30 minutes as the Rays’ half of the sixth inning stretched on in Game 3 of the ALCS. He had just committed his third error of the series and fourth of the postseason. He had also made some strong throws, but the bad ones were glaring: First baseman Yuli Gurriel had rescued four or five others since the playoffs began.

The first error in Game 2 of the ALCS, a throw from rightfield that one-hopped Gurriel, had kept an inning alive. The next batter, Manuel Margot, immediately socked a three-run homer. Correa believes that sequence never quite left Altuve. “When those runs score, they hit you a little different, mentally,” Correa says. “He cares so much that, mentally, he was still thinking about that.”

Houston righty Lance McCullers Jr. had worked around the second error, but as the Astros took the field for the bottom of the fifth, Correa turned to his friend. “Do you want me to take the long throw?” he asked. “Yes,” Altuve said. He had risen from a $15,000 afterthought to a superstar because he believed in himself. Now, in the middle of a playoff game, he admitted he no longer did.

Correa needed to remain at his usual station with runners on base, but for every other lefty shift, they switched spots. The Astros still lost 4–2.

Now it was the sixth inning of Game 3. Tampa’s Brandon Lowe bounced a perfect double-play ball to Altuve, who took half a dozen steps to his left, gloved the ball, turned, fired to Correa … and spiked the throw eight feet shy.

The rest of the infielders gathered on the mound as Baker trudged out to make a pitching change. Altuve stayed on the dirt, looking as if he would prefer to be below it. One by one, Bregman, Correa and Gurriel tried to console him. “Keep your head up,” Correa said, adding that he should have made the play. “That’s on me,” he insisted. Later Correa would run Altuve through all the mistakes he had made in the series, reassuring his friend that the losses were not his fault alone.

None of it mattered. For the rest of the inning, Altuve never spoke to any of them. The Tampa hitters, mercifully, left him alone. He just stood there, tugging at his hair and swiping at his eyes. The Rays scored five times that inning, and won 5–2.

He did not make another error for the rest of the series. He also never resumed his place in the lefty shift with the bases empty.

The people who spend every day with Altuve revere him. Baker calls him “one of the truest guys ever.” Correa raves about his leadership. Bench coach and infield coordinator Joe Espada says, “He’s in a really good place right now.” To a man, they insist that he will be fine.

“To me it’s a moot point now,” says Baker. “He made two bad throws, and it was on national TV at the wrong time, and there was something to talk about. I mean, he made two bad throws. … S---, if a guy ain’t never made no bad throws, he ain’t never played baseball.”

Indeed, often the most effective cure for the yips is pretending they do not exist. Altuve traveled to Costa Rica with his family before the holidays, then after the first of the year began meeting Espada two or three times a week at Minute Maid Park. In a typical season, they will commence their work three weeks before spring training; this year, they began six weeks ahead of camp. Espada paints the choice as a casual one: “The season was really short, so I feel really strong; why don't we start doing some of our work a couple of weeks earlier?”

They did drills to focus on Altuve’s base, his footwork, his momentum. Espada reminded him to finish his throws rather than pulling off early. They reviewed tape. All pretty standard stuff, Espada says.

The team's office space looks out onto Minute Maid Field, so officials monitored Altuve's work. What they saw quieted any conversation of moving him. The Astros checked in on free-agent second baseman DJ LeMahieu, according to three people familiar with the talks, but a person with knowledge of those talks says they were more about LeMahieu than about Altuve: If you have a chance to nab a perennial MVP candidate, you take it, and figure the rest out later.

Baker insists they never seriously considered moving Altuve this offseason. “I didn’t even go down the road,” Baker says. “That road never even opened up. There was no gate to the road.”

Altuve says he never worried that the team would relocate him. He always believed he would be able to heal what ailed him. He looks back on those emotions from October as if they belonged to someone else. “It’s hard to remember,” he says, then explains: “Everybody that wants to do their job, they want to do it right. So when something goes wrong, it doesn't feel really good, but I think the key for me is to move on. Every year, it doesn't matter if I play really good or really bad; I try to get to spring training with my mind clear, and I think that's what has been working for me. So that's why it's kind of hard to remember exactly how I felt and what was going on in the moment.”

He does not call what happened to him the yips. He also does not attribute it solely to his body. “I don't know,” he says. “That's a good question. Probably a little bit of both. I mean, I felt good physically and mentally. But, you know, sometimes things happen.”

That particular thing is over, he says. He feels good. He believes the game will be fun again. He knows opposing fans, allowed back into ballparks, will jeer him, but he says he will feed off that energy. He is ready to play with intensity and bring a championship back to Houston.

Scouts agree: He has looked good this spring. He may indeed be fixed. But we won’t know for sure until the games count. Many sufferers of the yips feel fine on back fields or during exhibitions. On Opening Day or shortly thereafter, a groundball will head toward his glove. He will point his front shoulder at his target. He will find his four-seam grip. He will open his hips. And he will release the ball.