We’ve long been warned about the ravages of time. As today’s stars redefine what it means to be old, where does that leave the rest of us non-LeBrons?

Bob Myers was sprinting down a basketball court in the fall of 2017 when he felt a weird pain in his right leg.

At the time Myers was 42 and in his fifth year as the general manager of the Warriors. He loved his job—but what he really loved was playing the game. He’d starred in high school, walked on at UCLA and basically never stopped. Rec leagues, the YMCA, some dude’s driveway. Myers loved playing ball the way that some people love running or cooking or painting—with a deep, consuming passion that rushes up from the core. And in it he found not just joy but also identity and the escape that comes from a flow state, when the stress of life is muted and all that remains is the next possession or corner jumper.

Now that was threatened. When the ache spread to his hip, Myers chose the time-tested approach of athletes everywhere: He ignored the pain and kept going. And 10 years earlier that might have worked. The aging body, however, has a long memory. It didn’t matter that Myers was in ridiculously good health—he exercised daily, ate well and had the body fat of a greyhound. The invoice on all those years of sprinting and leaping had come due.

“It felt like my leg was exploding,” he says.

Illustration by Michael Marsicano

Myers underwent a series of surgeries, but none fixed the issue. Finally a doctor gave him the bad news: He needed a hip replacement. And this freaked him out. Partly because he saw himself as far too young for a replacement, and partly because of the recovery time, but mainly because of what it all might mean. He began inquiring about plastic versus metal, about the best surgeons and hospitals. But what he really wanted to know—the question so many of us ask at some point, whether we’re professional or weekend athletes—was: Will I still be able to play?

He was not yet ready to entertain the next question. What will I do if the answer is no?

Last February a giddily inebriated 43-year-old man staggered off a boat in Tampa. The world had a good laugh about it: Tom Brady looks hammered! That it was funny, even endearing, was on account of the context, because of course Brady never gets drunk (that we know of). He supposedly monitors everything that enters his body, much as a trader monitors the tiniest fluctuations in the market, surviving on a diet void of sugars, starches, dairy or anything else that tastes good or is fun to eat.

Brady is among a cadre of athletes redefining what it means to be old, at least by the standards of pro sports. Oksana Chusovitina, a gymnast from Uzbekistan, just competed in her eighth Olympics, at 46, while Sue Bird won her fifth gold medal in basketball, at 40. In May, Phil Mickelson became the oldest golfer to win a major, at 50. The list goes on. Diana Nyad swam from Cuba to Florida at 64. Hélio Castroneves won the Indy 500 at 46. Vince Carter kept dunking in the NBA right up until he was 43.

Still, for decades we’ve been warned about the ravages of time. Starting around age 35 we begin to lose roughly 1% of our muscle mass every year. Simultaneously, we become more prone to injury, as our ligaments and tendons stiffen and our cartilage thins, like an eraser wearing down to the nub.

Meanwhile, our average VO2 max—the amount of oxygen our body can use during exercise—drops by roughly 10% in our 40s, 15% in our 50s and 20% in our 60s, accompanied by a steady decline in reaction time and bone density. Like our smartphones, our bodies are designed for obsolescence.

And yet: Today’s sports heroes play longer and better than ever before. They benefit not only from the inherent genetic advantage of all great athletes, but also from decades of elite training, cutting-edge treatments and the time and money to enact them. LeBron James, who played MVP-caliber ball last year at 36, reportedly spends more than $1 million of his own money on his body annually. He employs a personal biomechanist (former Navy SEAL Donnie Raimon), receives liquid nitrogen treatments to reduce inflammation and enjoys the benefits of expensive hot and cold tubs in his home. Steph Curry (still relatively young at 33) swears by float spas and cryotherapy. Roger Federer (40) owns a hyperbaric chamber and sleeps 10 to 12 hours a night in absolute darkness.

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

Inspirational though they may be, these athletes are about as relatable as aliens. Most aging Americans instead resort to quick fixes to stay active, and marketers are happy to oblige. The anti-aging industry accounts for more than $40 billion in annual sales, affecting what we buy, eat, slather on our face and, in some cases, inject into our bloodstream. Using terms like wellness and rejuvenation, and banking on our collective fear and vanity, the largely unregulated industry hawks products that so often make impossible claims, igniting in us conflagrations of hope.

The result: While pro athletes are encouraged to age gracefully—Know when to hang it up!—the rest of us believe that we can be 70 and rocked. That we should emulate 85-year-old marathoners. That if Tom Brady can keep going, so can we.

Thus, hope stirs in the belly of people like Bob Myers—and perhaps you. Maybe we can play forever, or close to it. Maybe the end can be continually pushed ahead of us, like a hockey puck nudged forward again and again. The upside is significant: Study after study says that to play longer is to increase happiness, well-being and lifespan.

Deciding to push on can be easy. The difficult part is deciding how much you’re willing to sacrifice to do so.

The history of humans doing questionable things in hopes of performing longer and better goes back millennia. In ancient societies men ate the testicles of animals, and sometimes of their foes. Greek Olympians were big fans of hallucinogens, while French cyclists in the 1800s drank a mixture of wine and coca leaf—liquid cocaine, essentially. In the late 19th century, in Paris, a professor named Charles Edouard Brown-Séquard became a sensation after announcing that he’d developed a concoction, composed of the crushed testes of dogs and guinea pigs, that boosted his strength and stamina to heroic levels. An opportunistic American baseball player named Jim “Pud” Galvin injected the elixir, thus marking, as Bill Gifford notes in his book Spring Chicken, “the first recorded modern use of a performance-enhancing substance by an athlete.” (Shockingly, Galvin found no clear advantage.)

By the early 1900s athletes had experimented with heroin, ether and, in one case, strychnine mixed with brandy (which almost killed an Olympic marathoner). In World War II, superpowers began dosing soldiers with amphetamines to fuel them through battle despite sleep deprivation. It didn’t take long for U.S. troops in military sports leagues to realize that “greenies”—or “la bomba” as Italian cyclists came to call them—also did a damn fine job of keeping you focused on a game. “After that, they spread like wildfire in all types of sports,” says Charles Yesalis, a professor emeritus at Penn State who has written extensively on performance enhancers in athletics. By ’58 the FDA had approved anabolic steroids. (It would be another 30 years before they were banned for nonmedical uses.)

At the same time, a sea change was occurring in how we view exercise. In the late 1960s and early ’70s regular people began running, not just to catch the bus but for fitness and longevity. Jane Fonda and Richard Simmons and Jim Fixx became icons. Weightlifting, long avoided in high-level sports for fear of injury and decreased flexibility, was embraced. Jack LaLanne begat Pumping Iron, which begat skinny teens in basements straining away on Soloflex machines, which begat, eventually, jacked moms Crossfitting in temperature-controlled studios.

Meanwhile, each decade brought leaps in our understanding of nutrition and training. Gone was the athlete who took a shot of whiskey before a game to calm their nerves, or a smoke break at halftime, as Vlade Divac was known to do. As technology advanced, professional careers extended. In 1982 the NBA counted only one player 35 or older, Elvin Hayes. Last season there were 16—and that trend is mirrored throughout sports.

Eventually, inevitably, the anti-aging industry and the athletic performance industry intertwined, with weird results. Now, HGH and testosterone are no longer solely the tools of bodybuilders, MLB sluggers and NFL linemen, but also of CEOs, bankers and life hackers. Now, science and salesmanship can be hard to separate; outcomes are murky—enhancing performance doesn’t necessarily mean extending longevity—and those people with time, money and privilege have a huge head start on the rest.

Now, we live in an era of possibility. Even if many of us don’t yet know it.

In June the Nets lost to the Bucks in Game 7 of the Eastern Conference semifinals, in large part because one of their three stars, Kyrie Irving, was out with a sprained right ankle, and another, James Harden, was hobbling on a Grade 2 right hamstring strain. The third, Kevin Durant, who’d recently returned from a devastating right Achilles tear, couldn’t single-handedly will his team to the Finals, though he came preposterously close. One month later, with eerie timing, the team’s owners, Joe and Clara Tsai, announced the launch of a grand initiative aimed at furthering the science of performance and longevity.

The nonprofit, which the Tsais funded with $220 million, brings together six top research schools in hopes of applying rigor to a field laden with anecdotal information. That the Tsais’ Human Performance Alliance sounds like something out of a Marvel movie is not intentional, but it matches the scale of ambition. Over the next decade the foundation will take “moonshots” in a variety of fields and share the results widely. “Open-source science,” director Scott Delp calls it.

Delp, a compact man in his 60s, is the chairman of Stanford’s department of bioengineering as well as a devoted adventure racer. His lab, which serves as the Alliance’s de facto hub, creates predictive digital replicas of athletes, based on their workout and injury histories. (One aim: to improve the accuracy of smartwatches, which Delp says show a “40% to 80% error” in measuring caloric burn.)

Elsewhere in the Alliance, Kathryn Ackerman, director of the Female Athlete Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, focuses on decreasing the likelihood and severity of injuries among women, including bone fractures and ACL tears. While the Alliance doesn’t focus exclusively on aging-related issues, the research is particularly applicable to those in midlife and beyond because, as Delp puts it, “it’s not time that does in athletes—it’s injuries.”

Listening to these scientists can feel like a peek behind a curtain. At the Salk Institute in San Diego, Satchidananda Panda studies circadian rhythm from a genetic standpoint, and he’s found that thousands of genes in our organs “turn on” at certain times of the day, primarily dawn and dusk, allowing us to make greater gains in muscle-building and in recovery when we have strong circadian rhythm. (For this reason, he now exercises around 6 p.m.) He’s also discovered unexpected benefits to time-restricted eating, often hyped as “intermittent fasting.” When Panda fed mice exclusively inside of an eight-to-12-hour window, the animals doubled their endurance on a treadmill and their muscle mass rose significantly, all without additional exercise. The reason is simple: If your body is busy responding to all the food you put into it, it can’t enter recovery mode.

Illustration by Michael Marsicano

At UC Davis, Keith Baar, a molecular physiologist and Alliance affiliate, will tell you that cartilage is not, in fact, a finite resource. Not only can you preserve it, but in some cases you can also regenerate it. (One method involves consuming gelatin before working out; another, the so-called hyena diet, entails eating all the chewy parts of meat.) Baar has determined, too, that a targeted 10-minute session of isometric holds, performed six to eight hours before sports, can strengthen tendons, ligaments and cartilage, reducing the threat of injury. In one study, he worked with a pro basketball player who suffered from patellar tendinopathy. “You could see a hole under his kneecap on the MRI,” says Baar. After a season of the exercises the hole disappeared. Now imagine what that could do for a rickety 50-year-old.

Of course, this 50-year-old would first have to know about the process—which leads us to a persistent issue in the field: information flow. Breakthroughs essentially arrive in time capsules. Baar estimates that it takes five years for a discovery made in a lab to trickle down to athletic coaches and trainers, and another decade to reach the rest of us. For most midlife athletes, that’s far too late.

Part of this is that, well, science is confusing and difficult to explain. Another factor is that incremental advances don’t often qualify as news. But, mainly, it has to do with money. Take Baar’s exercises. His routine is simple, easy to explain and doesn’t require an app or a $9.99 subscription or a gizmo that Shaq can hawk on late-night television. Which also means that it’s almost impossible to monetize (though no doubt someone will try). “People are making a lot of money by making things seem more complex,” says Baar. “If you say, ‘Actually, it’s really easy,’ they say, ‘You’re going to lose market share.’ ” (There’s a reason one of the only free fitness phenomena in recent years, the seven-minute workout, is so effective and widespread: It was designed by a professor, not a for-profit company, and distributed by The New York Times.)

All of which brings us, in a very roundabout way, back to the Nets. Because, as remarkable as Durant’s playoff performance was, almost as remarkable was the speed and extent of his recovery from an Achilles tear, an injury that, until recently, effectively ended careers. Money and expertise certainly helped—the Nets equipped Durant with an antigravity treadmill and employed biosensors to track his motion—but so did information. If you knew even a fraction of everything Durant’s team knows about treating and preventing injuries, you’d be infinitely better equipped to avoid them as you aged. Instead, for most of us, a 10-year lag might as well be a lifetime.

Now, imagine if that lag were to shrink, while the science kept improving. In this world, which may not be too far off, we’ll be able to model and identify incipient stress fractures before they form. We’ll be able to replace parts rather than repair certain injuries. (Baar has already grown ligaments three centimeters long in a lab.) We may be able to take a safe oral medication that can effectively halt, if not reverse, the age-related loss of muscle strength. (Currently in preclinical trials, the drug works by inhibiting an enzyme called 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase.) Already, we can begin to play the odds. Anyone can send a cheek swab to the Bay Area lab AxGen and receive an algorithmic breakdown of their injury risk based on DNA comparisons with a database of 500,000 people.

In this world, Durant would not only recover more quickly, he would also, theoretically, never even suffer such an injury in the first place. And neither might you, no matter your age. But what if the damage is already done?

Athletes, it is often said, die two times. The second is the final curtain that awaits each of us. The first is when they can no longer compete.

No one is ready for the end when it comes. Steve Kerr certainly wasn’t. After the Warriors’ coach retired as an NBA player in 2003, at 37, he knew he would miss basketball, but he also had grand plans for the second half of his athletic life. He would play tennis. Lower his golf handicap. Maybe run a marathon.

And at first he did. He and a friend played epic tennis matches, crushing backhands and sprinting across the court. Then he came home one day and noticed his left knee hurt like hell. A month later it was the right. A doctor told him: You’re bone-on-bone. You can’t play hardcourt tennis anymore. And Kerr, then 42, was floored. “I was totally unprepared,” he says. Within a year he gave up high-impact sports entirely; within five he needed back surgery. When that went poorly, Kerr faced a world in which competitive exercise—fuel for someone like him—was replaced by monotonous sessions on the stairclimber. It hit him hard.

“Phil Jackson used to talk about retiring from playing as a ‘death’ and tell us we had to prepare for the loss,” says Kerr. “I used to think he was being a bit dramatic. Now I understand exactly what he was talking about.”

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated

Kerr’s situation is unique, but his struggle is common. For years Michelle Silver, a sociologist at the University of Toronto, studied doctors as they shifted from being on call to doing secondary work to eventually retiring. And she found that, at the end, they essentially fell off a cliff. One day they were respected and passionate, with a clear purpose. Then they were just normal people.

Silver turned her focus to sports and found athletes weren’t much different. Robbed of identity and purpose, the people she studied often fell into depression after retiring. They got divorced and remarried, in search of meaning. Some turned to substance use or otherwise lost their way for years, decades. Others just never adapted to a life where they couldn’t be the athlete they once were—where they couldn’t be the strongest in the gym or the fastest on the track. Instead, they gave up on the sport they loved. “There should be a manual for managing this,” Silver says. “Aging has become something to be feared, more than ever.”

I remember the last time I felt immortal. It was 2011 and I was 37, sitting in an orthopedist’s office, annoyed my appointment was taking so long. Then a doctor walked in, held up an X-ray and told me, in so many words, that I had the hips of a 70-year-old. Undoubtedly, this had to do with my having spent decades playing basketball every chance I got. “You’ll need to replace the right one,” he said. Not somewhere in the distant, hazy future. Soon.

I tried to buy time. Physical therapy helped for a while. Cortisone shots gave momentary relief. The first one earned me a month of hoops. The second bought me a week—but, oh, what a glorious week it was, sprinting and leaping pain-free. I didn’t realize it in the moment, but it was the last time I’d ever feel that way.

Six months later there I was lying on a gurney in a San Francisco hospital at 6 a.m., unable to feel much below my neck, staring up at a man with perfect teeth as he told me, “This will only take a moment.” When I woke up I’d have a new hip. I had nothing to worry about.

“Did I do a great job?” he asked many months later, after yet another complication. “Maybe not. But did I do a good enough job? I’d like to think so.”

The hardest part was not the recovery, or the rehab, or the cane, or the freak-outs about addiction to painkillers. The hardest part was adapting to the new me. My doctors were clear: You can ride a bike. You can swim. You can walk. But no more running. And definitely no more basketball.

This wasn’t a viable option. I’d grown up playing ball and had never stopped, competing in three rec leagues a week into my 30s. I thought back to the conversations about aging that I’d had during my years as a sportswriter, and how each of us deals with the imminent end in different ways, from denial to unrealistic optimism to going cold turkey. I remembered Pistons coach Rick Carlisle, sitting in his office back in 2002, only 42 and not far removed from his days as an NBA shooting guard, telling me that he no longer played the game, not even for fun. That he didn’t miss it. I thought about a 35-year-old Kobe Bryant, at a hotel in China, just before his body broke down, insisting that he had another five years in him—that he would be the one to defeat Father Time. I thought about surfer Laird Hamilton, at 53, saying, “I’m not going to fall victim to what I’m supposed to do at any certain age.” I thought back to a conversation with Mavericks owner Mark Cuban, with whom I have little in common other than crappy hips, and how he gushed about his life after a double replacement.

Illustration by Michael Marsicano

And I thought back to an email I’d received from a writer friend whose passion for playing ball mirrored my own. “I injured my back yet again,” he wrote. “I’m back in physical therapy. Did the math and realized I have been injured and unable to play hoops 55 out of the last 72 months. My rapidly declining athleticism and eroding basketball skills have turned me into a net negative for any team I play on. It’s no longer fun to play. So I am done. And I am sad, yes, but also relieved. I feel like I did when I gave up booze 25 years ago, absolutely ready to give up the 10% of drunken fun so I would no longer have the 90% of drunken misery.”

The email hit hard. I should have been happy for him. Instead I felt betrayed. I wasn’t ready to give up the game. Already its absence had exacted a toll. I mourned the player I once was, able to rely on athleticism to cover for mistakes. I knew the new me would be different. Then I felt bad for thinking so much about it, considering all the vastly more important problems in the world, but that didn’t help either. So I saw more physical therapists. I took an anti-inflammatory, Mobic, before playing and drank electrolytes afterward. I bought expensive Hoka shoes to cushion my joints. I tore my plantar fascia (playing basketball) and developed knee tendinitis (playing basketball) and wrenched my back (preparing to play basketball). I dialed back to once a week, an hour at a time. I played only indoors, on a forgiving floor. I traded longevity tips with friends. I got a Fitbit and convinced myself that walking could fill my competitive void—and then walked so much that my knees hurt. I took up foam-rolling and dynamic stretching. I used a lacrosse ball to break up sore muscle tissue and tried to be a “supple leopard.” Finally, this summer, I drove five hours south to Santa Barbara to learn just where my body stood.

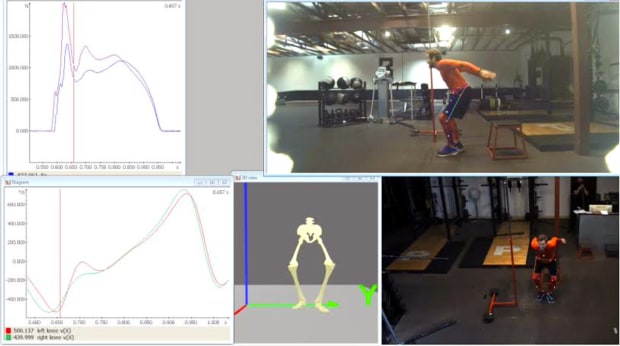

There, tucked down a side street in a nondescript building, is Peak Performance Project (P3). Using sensors, force plates and a battery of cameras, and plugging that info into its algorithms, the lab has been evaluating athletes for a decade. The P3 database includes more than 800 players with NBA experience, as well as hundreds of other elite performers. I first visited for a story in 2014, writing about P3’s role in injury prevention. As part of that process I, too, was evaluated. And among many humbling metrics, all charted against NBA players, I displayed the second-worst hip range of motion of anyone P3 had ever tested. That was at 40, right before my replacement. I was curious what I could learn from a side-by-side comparison seven years later.

Shortly after my arrival at the lab, the founder of P3 rolled in, hair still wet from surfing. Marcus Elliott, 56, trained at Harvard before entering sport science. He is the kind of guy who can talk at length, extemporaneously, on seemingly any topic; who, during the pandemic, moved with his family to a German mountain village and hiked every day and taught his daughter math; and who engages in regular misogi tests of endurance and mental fortitude in which the chance of success is intentionally designed to be 50%, for that is when he believes we learn the most about ourselves. The last time I’d come through, he and some friends, including NBA guard Kyle Korver, had recently finished taking turns diving to the bottom of a harbor 30 miles south of Santa Barbara while rolling a large stone two miles on the seafloor. The feat took five hours, and they nearly puked from exhaustion, but the sense of accomplishment, Elliott says, lasted months.

Now he took inventory, inquiring about my various ailments and recent health history, and arranging for a 3-D body scan, which produced a hyperdetailed image of my physique, down to discrepancies in my muscle strength and limb length. The lab’s lead physical therapist twisted and pulled on my appendages, pushing and prodding, trying to loosen up the tightest areas.

Then, as the P3 team had done seven years earlier, they attached nodes all over my body and put me in a red lycra top, which made me look like a deflated Mr. Incredible, so that I could flail through a series of exercises on force plates.

Courtesy of Peak Performance Project

Only this time, everything was more difficult. The plastic slats of the vertical jump rack, once easy to leap up and swat, seemed to tower over me. Whereas years ago I had deftly hopped back and forth over an iron bar to measure lateral speed, this time I was lunging. P3’s director of biomechanics, Eric Leidersdorf, watched as I went to great lengths to make up for the ravages of age and injury, landing duck-footed on the lateral test to better launch off my bad hip and nearly hyperextending my shoulder in attempting to reach just a bit higher on the vertical. “Bodies are master compensators,” Leidersdorf observed. This, it became clear, is not necessarily a good thing.

The numbers were exactly what you might have guessed. All my measurements were down between 5% and 10%. When I landed on my left leg, I had 90 degrees of hip flexion, which is decent; but on my surgically repaired right side, I got only 17, the worst of anyone they’d ever seen. My hips no longer absorbed force, Elliott explained, which is “the kiss of death for NBA players.” He also told me I was in the “Achilles rupture zone.” Basically: “What you’re doing”—playing basketball—“is super hard on your body.”

The good news: Hope remains. P3’s lead trainer guided me through two hours of exercises designed to activate my glute chain. I hopped from leg to leg; performed shoeless, one-footed deadlifts; pushed around 45-pound weights with the outside of my foot; and leaped repeatedly with hands on my hips, landing on both feet, like a sweaty Russian dancer. Afterward, I was directed to an $85,000 cryotherapy tank—basically, a futuristic phone booth, as imagined in an ’80s rock video, replete with frost pouring out. Inside, I watched a timer tick off three minutes as the Foo Fighters’ “Everlong” played and my body adjusted to the –220° chill, which, Elliott pointed out, “is colder than any of your ancestors have ever felt.”

After the training, the PT, the cryotherapy and some cooldown stretching, I felt fantastic. My joints were loose, my back lacked its usual rigidity and, placebo or not, the cryotherapy seemed to have chilled my hip pain. That night, drinking a beer, I experienced a wave of nonalcoholic euphoria. I’ve turned back the clock! Over-30 league, watch out!

Alas, the next day, as I drove back to San Francisco, joints stiffened as the miles passed, reality setting back in. I knew by that night, life would rush back over me—the deadlines and dog walkings, picking up kids from practices and all the rest. I would not have the luxury of spending the better part of a given day focused on my body. I would trade the lavish P3 facility—with its cryo tank and antigravity treadmill and compression pants and elite PTs—for the carpeted floor of my garage and a handful of free weights.

There had to be another way. One that didn’t cost P3’s $1,800 a month or require vast swaths of free time. One that the average person could replicate.

If there is a secret to athletic longevity, perhaps we can find it in the stories of regular people—the ones who started doing something and just kept on going, and going.

Someone like Julia “Hurricane” Hawkins, who two years ago set the world record for the 100-meter sprint in her age group. Hawkins, who’s now 105, credits her longevity to years of cycling, a balanced diet and having “many passions”—like tending to the jasmine, carnations and bonsai trees in her garden.

Or maybe we should look to Olga Kotelko, who held more than 30 world records and won 750 gold medals in Masters competition before she died at age 95, in 2014. Two research institutions studied Kotelko’s muscle fibers, each hoping to find the secret to longevity. Kotelko herself credited this endurance to listening to her body (she eschewed anti-inflammatories), getting good sleep, cross-training and eating most anything she wanted. “I don’t believe in diets,” she said.

Then there’s the approach of Deena Kastor. Growing up in Agoura Hills, Calif., in the 1980s, Kastor was a shy kid. She tried figure skating, then found social ease in distance running, excelling in high school and college. By 2000 she’d made the U.S. Olympic team; by ’06, she’d set a slew of records, including the U.S. women’s mark in the marathon. After taking bronze at the ’04 Athens Games, she entered ’08 as the favorite. Then, three miles into the race in Beijing, in what should have been the pinnacle of her career, she fell to the track. She’d broken the third metatarsal in her right foot—she recalls it being like a “popsicle stick snapping”—a debilitating injury for runners.

Kirby Lee/Image of Sport/US Presswire/USA Today Sports

In the aftermath, she expected to be devastated. Her mom kept calling, worried about her. But, strangely, Kastor says, she was O.K. with it all. The key to that acceptance, she believes now, was her outlook. For years, she’d fervently believed in the physiological benefits of positive thinking. “I immediately went from, ‘O.K., my goal of gold is gone, so I need a new goal, and that’s to figure out why I'm unhealthy and fix it so I can be healthier,’ ” she says. “It wasn't the goal I came into the year wanting, but—I think—because I practiced optimism for so many years I was able to reroute.” (Kastor's approach has scientific grounding; studies show that positive self-talk has myriad athletic benefits, including improving performance in endurance sports.)

From that point forward, Kastor never set another major record—but she didn’t stop running. She finished second at the New York City Half Marathon in 2010. She and her husband, Andrew, had a daughter, Piper, and they moved to the mountains. Now 48, Deena still puts in hundreds of miles each week, and she competes in Masters events. How? She points out that she gets between 10 and 12 hours of sleep each night. “We don’t have a TV at home,” she explains. “We eat dinner pretty early; we'll just chat as a family for an hour and then we could be in bed by 7:30.”

Kastor, like Kotelko, has no interest in supplements or magic formulas. She has yet to embrace age-adjusted times, as many runners do. Rather than go into a facility for cryotherapy, she says, “I’m going to go sit in a river or a lake,” describing herself as “a purist.” Recently, Piper asked her mom what her life goals were. “I'm like, ‘Oh, my God, you're 10 and you're asking me what my life goals are?’ ”

Kastor felt like she needed to come up with an answer. “I remember at the height of my career, in my 20s, I didn't think I'd be running at 40. And then, at 40, I'm like, ‘I'm not even close to giving this up yet.’ And now, one of my life goals is to live a lifestyle so I could run until I'm 100 years old.”

But how, exactly, does one do that?

Exercise. Not too much. Mostly planks. Were you to boil down the keys to athletic longevity, as Michael Pollan once did for nutrition—Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants—this might be where you’d land. Then again, it might not be. If I learned one thing by diving into this world—reading the research and deep-dives (this is an excellent book-length exploration), talking to the trainers and scientists and athletes—it’s that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Instead, it depends on who you are and how old you are, and it factors in your genes and injury history, your body’s response to food and so, so many other things.

What we do know, broadly, is that quantity, quality and timing are crucial when it comes to the three core elements of performance: exercise, nutrition and sleep. Even if you don’t have the time or the money to take advantage of the latest breakthroughs, you can eat nutritious foods at optimal times, sleep in a way that best allows your body to repair itself and target your workouts to your goals. Too little exercise will undoubtedly do you in, but too much can also derail the aging body, it turns out.

So: Strengthen your core—planks are good, as are plenty of other exercises—so you can play the sports you love. Maximize your exercise time; for example, research shows that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) may add years to your life by changing your gene expression. Cross-train, rest and don’t do stuff you shouldn’t, like running on concrete if your joints ache. Most of all, know your body. Perhaps you find that short, heavy lifts once a week work for you, as they do for Baar. Or maybe, like Kerr now does, you focus on flexibility as a path to longevity.

Illustration by Michael Marsicano

Or perhaps you emulate Elliott, the P3 guru who in his 40s began setting long-term goals. One was to peak as a generalist at 65—to be able to say yes to everything, whether it was soccer or surfing or playing with his kids. It’s essentially the opposite of his day job, which requires hyperspecialized training. (How can we make this NBA player a better perimeter defender in 12 weeks?) “Humans are such aspirational creatures. We relish the idea that we’re going to be better tomorrow than we were today,” Elliott says. But the big shift with aging is mental, embracing the idea that “you can really work at something—you can be really intentional—and your best hope is to only slowly get worse instead of quickly getting worse.” So now Elliott’s goal is to be “mediocre at everything.”

“[That] doesn’t really resonate with ambition,” he admits. “But it’s hard, as you go through life, to be able to say yes to everything.”

It certainly helps if you know what you are playing for. Hirofumi Tanaka, the 55-year-old director of the Cardiovascular Aging Research Laboratory at the University of Texas, does 15 minutes of HIIT training each day at his office, sprinting up and down the carpeted hallways, sometimes forward, sometimes backward. His goal is to continue playing soccer with his students, and he has a simple equation for when he’ll stop: “When it’s no longer fun.”

Which brings us back to Bob Myers, who played his last pickup game in March 2018. Afterward, the pain was too much. For a while, he says he even considered taking opioids. What really got him was the absence of basketball. “It’s always been my therapy,” he says. “Not being able to get out my stress physically was a huge blow.”

Being a methodical, organized sort, Myers spent months researching and calling all manner of people about hip replacements (including me—he wanted to know whether he’d still be able to play ball, and I told him he would, but it would be different). Then, last December, he underwent hip-resurfacing surgery. Afterward, he was disciplined in his recovery. But sometimes even the best information, access and care can’t overcome the complexities of the aging body.

Myers had heard about people who are back on the court in seven months. But seven months out he was still in significant pain. He began wondering whether he’d ever be able to play again. “The experience was humbling,” he says.

Finally, this summer, the pain subsided. His big takeaway, he says, is that we’re all different. “We all have to run our own rehab.” Now he proceeds cautiously. He does yoga and recently logged 23,000 steps at Disneyland with his kids. He’s taken up pickleball as a gateway sport, knowing it’s perfect for “the geriatrics with joint issues.” Meanwhile, he’ll start shooting baskets alone this fall, then he’ll play pickup with the old guys and, if that goes well, return to playing with “the whippersnappers.” In the meantime, Myers says it kills him to walk by a game—a feeling he acknowledges may not be entirely healthy. “But if you’re going to have a vice, you could have worse ones than pickup basketball.”

Going forward, he’s willing to sacrifice. “I’ll never stop wanting to play ball,” Myers says. “That’s probably the only thing that I 100% know.”

As for me, I’m still rehabbing, pre-habbing, counting my steps, warming up and cooling down. And, because of that—I think?—I’m still able to play hoops once a week, if creakily. Whenever I get injured, or frustrated, which is often, I think about my father, a stoic Midwesterner who played into his mid-70s, even after a double knee replacement. When his right shoulder crapped out, he learned to shoot lefty. He’s now 82; we played H-O-R-S-E not long ago.

He didn’t do any of this to be an example. Nor did he do it to pass on some lesson, though I intuited one, anyway. It took me years to pick up on it, but now I think I get it, and it’s what keeps me going: Eventually, what matters is not how you play, but that you play at all.

• A Predatory Culture, a Viral Reckoning—and Now What?

• Karl Anthony Towns Opens Up About His Season of Grief

• He Rose to the Highest Levels of Business and Basketball—but With a Secret