The team has acknowledged providing "minimal" PR help to the local Church on its sexual abuse crisis—but an SI investigation found that the Saints’ aid was more extensive.

Kevin Bourgeois’s phone was ringing. It was a Wednesday in January, three weeks after the Saints’ season had ended, and he was standing in the parking lot outside the team’s headquarters in Metairie, La., wearing a black-and-gold Taysom Hill jersey. Around him, a small group was assembling: One man sported a Drew Brees jersey, another that of LSU’s Joe Burrow.

Bourgeois recognized the number calling. The 53-year-old New Orleans native has been a Saints season-ticket holder for a decade, with seats in a row of the Superdome’s terrace level where he can stand the whole game without blocking anyone. Usually, when he sees the team’s switchboard pop up on his phone, it’s a sales rep asking about renewing his seats. But he knew that wasn’t the reason for this call: The Saints’ top legal counsel wanted a word.

Five days earlier, on Jan. 24, the Associated Press had published a story revealing that the team had performed public relations work for the Archdiocese of New Orleans related to its spiraling sexual abuse crisis. The news sent shockwaves across the deeply Catholic city, which has been rocked over the last two years by ongoing revelations of abuse by clergy members and Church employees.

Now the Saints, the city’s other great devotion, had come to the Church’s aid. A civil suit filed against the archdiocese by a former altar boy in October 2018 had uncovered hundreds of emails that allegedly show executives from the Catholic-named NFL team working with local Church officials on the crisis. Most of those emails are confidential—under seal and accessible for reading by only the lawyers involved—but some that have become public clearly show a Saints executive advising the Church on PR strategy.

Team owner Gayle Benson—known for her close ties to the Church and, in particular, to New Orleans Archbishop Gregory Aymond—has acknowledged that her team provided PR help. But as the Saints’ season ended with a playoff loss, its legal team fought in court to keep the emails under seal, raising questions over whether the Saints were hiding something. For now, that legal battle is on pause: The local archdiocese filed for bankruptcy in early May, freezing all its civil proceedings. The team declined to comment on the emails, citing a judge’s instructions.

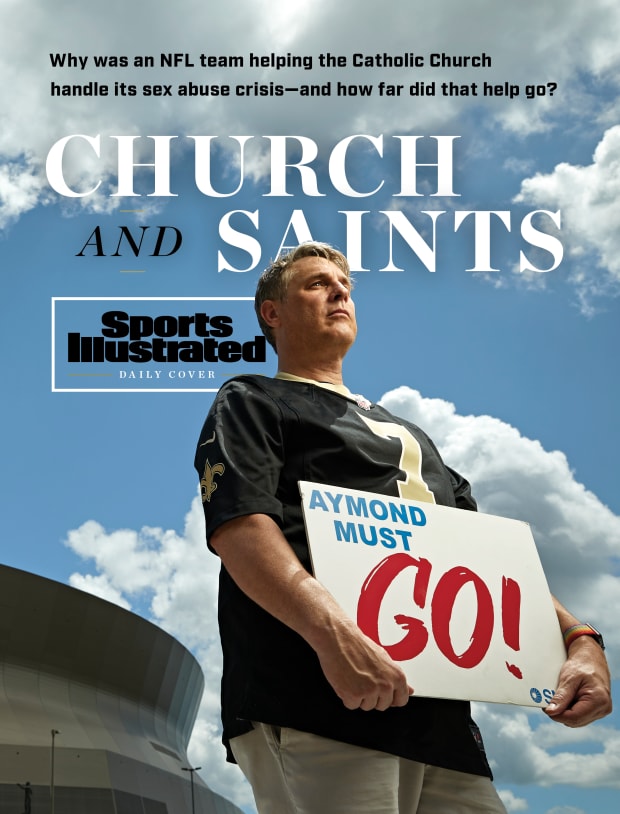

Bourgeois and a handful of other men had gathered at the practice facility to demand transparency. They are Saints fans—and also local leaders of the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests, or SNAP. Bourgeois was a teen attending a New Orleans prep school for students interested in the priesthood in the 1980s when he says his choir director, a priest named Carl Davidson, molested him during sleepovers at Notre Dame Seminary. (Davidson died in 2007; Bourgeois settled a claim with the Church in 2019.)

Vicky Neumeyer, the Saints’ general counsel, had already called Bourgeois a few hours earlier. She asked to meet for coffee, he says, which he took as an effort to head off the demonstration, and he turned her down. Now, on the phone, she wanted Bourgeois to meet her inside. He put down his AYMOND MUST GO! sign—he says the security guards told him he couldn’t take it in—and walked into the lobby. Neumeyer met him, carrying a stack of press releases for the reporters gathered outside.

“She was scolding me for being there and questioning what we were doing,” Bourgeois recalls. “I said, ‘We’re serious about this. If the Saints had involvement in this, we have a right to know. And there’s a lot of people in the public, in this city, that are livid that your organization weighed in on pedophile priests.’

“She said, ‘Well, I am just disappointed.’ Then as I was leaving, she goes, ‘Behave out there.’ ”

The Saints disputed Bourgeois’s characterization of the exchange, describing it as “cordial,” a lawyer for the team wrote to Sports Illustrated. “Saints personnel did not scold anyone or do anything to stop the gathering,” the statement read.

Nevertheless, Bourgeois was appalled. The press release Neumeyer gave him only made him feel worse: In the first line, the Saints described themselves as “an organization recognized for unity and healing,” the identity it proudly forged in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

The release then reiterated the Saints’ previous public account of “minimal” involvement with the Church’s scandal: The team said it was contacted by the archdiocese for PR help specific to managing its release to the public of a list of 57 “credibly accused” clergy in November 2018. The Church billed this list as a decisive public airing, one that would include names dating back decades. The list could affect survivors’ ability to seek settlements from the Church and allow them to feel a measure of justice. The Saints have consistently said that they advised the Church to be “fully transparent,” never disclosing any work on the abuse crisis beyond their assistance in the weeks leading up to the list’s publication.

But an SI review of case files and public records suggests that the team was significantly more involved in the archdiocese’s response to the sexual abuse crisis than it had acknowledged. When questioned by SI, the Saints conceded that a top executive had advised the Church on PR months before the release of the list, apparently shifting the timeline the team has promoted since January. A lawyer for the team said that, in the summer before the list’s release, Saints senior vice president of communications Greg Bensel advised Archbishop Aymond on general press strategy related to the abuse crisis.

“Mr. Bensel did receive a call from the Archbishop during the summer asking Mr. Bensel for his opinion on the best way to handle the press and the negative series of media articles that were being written,” James Gulotta, a lawyer for the Saints, wrote in an email. “Mr. Bensel suggested that the Archbishop call for and meet with the local newspaper’s editorial board.”

A spokesperson for the archdiocese declined to respond to a detailed set of questions, citing the ongoing Church bankruptcy proceedings.

The Saints, Bourgeois said after learning of the revised timeline, “are not to be trusted.” He and several other survivors who spoke with SI—including the daughter of a former Saints linebacker—say the Saints must offer a full public accounting. Why did the NFL team, one of the two most powerful institutions in New Orleans, join forces with the other for anything related to clergy sexual abuse? And how far did the Saints and Benson’s involvement go?

***

In July 2019, Gayle Benson and a group of Saints and Pelicans executives—Benson owns the local NBA team, too—went on a trip to Israel with Aymond. For years, the team has positioned its relationship with the Church as a point of pride. Gayle, 73, met her late husband, Tom, who died at 90 in 2018, at the famed St. Louis Cathedral in the French Quarter; the story goes that she had been fundraising for the church and was introduced to Tom by a monseigneur who suggested that the Saints owner could help with a new cathedral roof. Aymond led the pregame mass before the Saints’ only Super Bowl win, in 2010, and performed the Bensons’ 10-year vow renewal, in ’14.

Bensel, a longtime member of the Bensons’ inner circle, posted a group photo from the trip on Twitter on July 23: He’s standing with Benson, team president Dennis Lauscha and Aymond. “Special week,” Bensel wrote, adding that they were praying for a championship season.

A few days later the Saints received the subpoena that changed everything. It stemmed from the lawsuit brought against the Church by the former altar boy, identified as John Doe, who said that he was sexually abused by former Catholic Deacon George F. Brignac over a five-year period beginning in 1977, when the plaintiff was in third grade at Holy Rosary School. Brignac, who has been charged with the first-degree rape of another Holy Rosary altar boy, was removed from ministry in 1988 after police investigated multiple complaints that he had inappropriately touched children. He has denied all wrongdoing and is awaiting trial.

In the John Doe case, the Church produced a batch of documents to the plaintiff’s lawyers, which included emails sent by Ramon Vargas, a reporter for The New Orleans Advocate, in October 2018 to Sarah McDonald, the archdiocese’s director of communications, and Wendy Vitter, its then legal counsel, asking for comment for a story about the filing of the suit. There was also a separate email, sent about an hour later, from Bensel to McDonald and Vitter. It was days before the release of the list, and Bensel was working with the Church.

“Ramon reached out [to me] about that article. Is there a benefit to saying we support a victims [sic] right to pursue a remedy through the courts?” Bensel wrote.

“I don’t think we want to say we ‘support’ victims going to the courts but we certainly encourage them to come forward,” McDonald replied.

This exchange surprised the lawyers for John Doe: Finding the NFL team in the middle of a Catholic Church lawsuit made about as much sense to them as seeing a priest start at left tackle. As one of them, Richard Trahant, put it in a hearing: “Why do the Saints want any role in what is otherwise a toxic issue?” To find the answer, he and his cocounsels requested a subpoena for all the team’s communications with the archdiocese.

Over the last few years, many lawyers in New Orleans have guided survivors to quiet, out-of-court settlements with the Church. But Trahant has allied with two attorneys from other firms in the city, John Denenea Jr. and Soren Gisleson, to pursue a different strategy for the dozens of survivors whom they corepresent: They’ve sought transparency via every available legal avenue—prompting the Church in one court appearance to describe their efforts as a “witch hunt.” Now their target was the Saints.

In response to the subpoena, the club produced 305 emails in December, 276 of which they marked confidential, arguing that private communications produced through discovery do not need to be made public unless they are admitted into evidence. Trahant and his cocounsels contested this, pushing for release. State civil court judge Ellen Hazeur appointed a special master, in this case a retired judge, to assess the matter; in April, the special master sided with the Saints, but Hazeur, who has final say, had not yet ruled when the Church’s bankruptcy froze the case. In a January court filing, the Saints’ lawyers accused John Doe of wanting to make the emails public for “attracting publicity to his case.”

Benson has defended herself and her team, saying in a February statement that she was “proud” of the Saints’ assistance to the church. She laid out a lengthy description of the team’s role in the statement: “Greg Bensel . . . was asked if he would help the Archdiocese prepare for the media relative to the release of clergy names involved in the abuse scandal.” (Gulotta told SI that it was federal judge Jay Zainey who, acting as a friend of the Church, made this outreach to Bensel.) Benson’s statement continued, “In the weeks leading up to the Nov. 2, 2018, release of clergy names, Greg met with the Archbishop and communications staff.” Neither Bensel nor anyone with the Saints, she added, offered any input on which names were on the list, which has come under fire for its omissions. An AP investigation found the Church failed to include at least 20 clergy members who had been identified in lawsuits or charged with sexual abuse crimes (there are currently 63 names on the list, up from 57).

But in court papers filed earlier this year, Trahant & Co. said that emails showed the Saints “initiated this entire situation” and even pulled in other community leaders. The lawyers also alleged that the Saints “appear to have had a hand in determining which names should or should not have been included.” They wrote, “It cannot now be disputed that the Saints had actual involvement in the creation of the Pedophile List.”

Bensel is the only Saints official whose involvement with the Church scandal has been publicly identified: On the day of the list’s release, one of the archdiocese’s lawyers said in a hearing, his duties included accompanying the archbishop as he made interview rounds with the press. Bensel, the lawyer said, wanted “to provide aid to his archbishop.”

But Trahant and his colleagues have alleged in court papers that the emails show multiple Saints executives working to protect the Church’s image, using their team email addresses. That Benson has declared, “We are proud of the role we played,” only cemented the impression that it was the NFL team—not just an executive on his own—aiding the Church.

Inspection of the public record has revealed inconsistencies in the Saints’ account. The subpoena sent to the team asked for, among other things, documents “illustrating the authority of Greg Bensel to advise, direct, suggest, or counsel the Archdiocese of New Orleans.” In response, the Saints provided an email exchange between Benson and Bensel, dated July 8, 2018.

This date is significant for two reasons. First, it was more than three months before the archdiocese’s announcement that it would be releasing a list of credibly accused clergy—well outside the Saints’ timeline of helping the Church “in the weeks leading up to” the list’s publication. Second, July 8 was the day after The Advocate reported that Brignac had still been serving as a lay minister at St. Mary Magdalen Church in Metairie, 30 years after the Church had removed him from the ministry. A plaintiff’s court filing indicates that the first of the hundreds of emails the Saints produced related to their dealings with the Church was sent on July 8; the email remains confidential, but the filing states that it included discussion of this Advocate article—in other words, a topic other than the list.

The Saints now acknowledge that Bensel was in contact with Aymond during this time period. The plaintiff’s filings also show that correspondence between the Church and team continued for eight months after the list’s release, until the Saints’ records were subpoenaed.

***

Linda Lee Stonebreaker has a fleur-de-lis tattooed on her left wrist. She got it on a trip back home to New Orleans, where she spent most of her childhood. She has memories as a kid of piling into the family station wagon with her four siblings to go pick up their father, Saints linebacker Steve Stonebreaker, at the airport after road games. She chose blue ink because it reminds her of the comfort she felt upon seeing the cobalt-blue lights lining the runway—that meant her dad was almost home.

“I was once proud to be associated with the Saints,” says Stonebreaker, 56. “My first memories were climbing over my dad’s helmet when we were kids. And so it’s hard to be betrayed by a group of people that you’ve had such love and affection and pride for.”

Steve was one of the original Saints in their 1967 expansion season—a linebacker who secured a place in team lore that year when he responded to a New York Giant’s cheap shot by starting a bench-clearing brawl in Yankee Stadium. The following year, Linda Lee was 4 1/2 years old when Father Louis LeBourgeois gave her a ride home from preschool. When he pulled up her dress in the front seat of the car, she thought he was checking to see whether she had wet her pants. That’s when she says LeBourgeois digitally and orally raped her; afterward, he warned her that if she told anyone what had happened, God would send her to hell, and her parents would not love her anymore.

Stonebreaker repressed the memory until 1995, the year her father died by suicide and her older daughter turned four. She says she reported the abuse to the Church and police two years later, but was told the criminal statute of limitations had passed, and the Church took no action. She called Church authorities again in 2014, and they began an investigation. Stonebreaker says Aymond told her that LeBourgeois denied her account, but the priest died in ’15, before he could be interviewed by the Church’s investigator.

Nevertheless, the archdiocese agreed to pay for Stonebreaker’s weekly therapy appointments. She was surprised, then, not to see LeBourgeois’s name included on the archdiocese’s list of credibly accused clergy members. The omission not only felt like an invalidation of her experience, but also an impediment to the Church’s finding and helping others he may have abused.

More than a year later, when Stonebreaker learned that the team both her father and brother Michael played for had provided PR advice related to the release of the list, she fell into a depression. “I just felt so betrayed, shattered, crushed, [in] disbelief,” she says. Just a few months later, she says, the Church stopped paying for her therapy, amid its bankruptcy.

“I was deemed credible. Then the therapy started. That was the process. So, why isn’t that man’s name on the list?” Stonebreaker asks.

The Saints said they did not learn of Stonebreaker’s story until she spoke out publicly after the list’s release; she says she has never heard from the team. She sued the Church, but her case was frozen by the bankruptcy.

Stonebreaker, who believes brain injuries from her father’s playing career contributed to his suicide, says she has no plans to watch football again. “It’s hard that my father gave his life to a sport and gave up his life, and endured the pain that he did endure,” she says. “And then for that game and that institution that he revered and loved so much, to then turn around and betray his own child . . .”

Stonebreaker is not alone in dismay. Michael Brandner Sr., a Saints season-ticket holder, told SI that the church left off a priest named Brian Highfill, who met his brother Scot when he was a 10-year-old altar boy. After Scot died by suicide in 1993, Brandner says he discovered letters Highfill had written expressing love and yearning for the boy he used to take on camping trips. Brandner’s allegation, which he says he shared with Aymond in August 2018, is mentioned in a lawsuit filed by another survivor who described abuse by Highfill. (Highfill denied these claims in court papers.)

The list carries meaning for survivors, Brandner says, and “is no place for a sports franchise to use its resources.”

For Stonebreaker, Brandner and the SNAP advocates, a simple question lingers over the list: What exactly was the Saints’ role? Did team executives help shape the names on it? Did Benson, Bensel or any other Saints employee know the details of the allegations against certain priests and weigh in on whether they should be included? Court papers filed by John Doe’s lawyers cite a Nov. 2, 2018, email they say references Bensel’s participating in a conference call, apparently to discuss “removing priests from the pedophile list.” The Saints deny Bensel, or anyone associated with the team, was involved in adding or removing names.

The survivor in the current criminal rape case against Brignac, who asked to go by only his first name, Michael, said he was reconsidering whether he’ll renew the season tickets he’s held since 2006. As a condition of his 2018 settlement with the Church, Michael says the archdiocese promised him Brignac was no longer allowed near children. That was just weeks before The Advocate revealed that Brignac had been serving as a lay minister in Metairie.

John Anderson, who was wearing the Burrow jersey at the SNAP protest in January, says the Saints had previously been a helpful escape from his experience with posttraumatic stress disorder. He was nine when he told his mom that Brignac molested him during his afterschool class at St. Matthew School. This was the first time Brignac was arrested, in 1977. (He was acquitted, then transferred by the Church to teach at Holy Rosary.)

“When the Saints do this, it sets us back to an area where we don’t want to be anymore, because of the hidden things that are going on behind our backs,” Anderson says. “Now, instead of using this for therapy, I’m using it almost as a war against myself. I need to know if anything was said about me. I need to know what went on with Brignac.”

***

Two days after the release of the Church’s list, Gayle Benson was in the congregation at St. Louis Cathedral, wearing a gold sequined dress. Sunday Mass began with a short prayer for survivors of sexual abuse. During the recessional, Benson followed the 70-year-old Aymond out of the church, according to the Times-Picayune, and gave him “a long hug” before leaving. That afternoon, the Saints hosted the Rams.

Beyond their name, the Saints have long had a unique relationship with the Catholic Church. In this metropolitan area of 1.2 million, where counties are called parishes and about 43% of residents are Catholic, the Church plays a very large role. It became routine for Aymond to accompany the Bensons to Saints and Pelicans games or fly on their private plane; he even arranged an introduction for them with Pope Benedict XVI in St. Peter’s Square. Gayle, a former interior designer, redecorated Aymond’s residence. In July 2015, the archbishop served as a witness to the signing of Tom’s final will, gracing the normally mundane legal formality. The document left Gayle, his third wife, at the helm of a business empire grown through auto dealerships and banking—cutting out Tom’s daughter from his first marriage, Renee Benson; and grandchildren, Rita and Ryan Benson LeBlanc. There was a nasty legal fight; in March four national media outlets petitioned the New Orleans civil court to unseal the court record, citing public interest in the team’s leadership due to its work assisting the Church (Gulotta said Tom Benson’s legal successors intend to oppose the unsealing of the record, after the judge sets a hearing on the motion. Gayle was Tom’s sole beneficiary, and Lauscha, the team president, is the administrator of the estate; Bensel and Saints GM Mickey Loomis were named as next in line to be coexecutors).

Before the archdiocese’s bankruptcy filing, as part of a separate case, Trahant’s group of lawyers also sent subpoenas to the Saints and to the Bensons’ charitable foundation. One of the requests to the foundation was for documentation of any funding for settlements of claims for clergy abuse. Aymond had acknowledged in an August 2019 Advocate article that that the archdiocese has drawn on contributions from benefactors to help fund these claims, but the foundation said it had no such documents.

Benson said in her February statement that she was “sickened” by the suggestion that she would offer money to the Church for such settlements. “Neither Tom Benson nor myself, or any of our organizations have ever contributed nor will ever make payments to the Catholic Church to pay settlements or legal awards of any kind, let alone this issue,” Benson’s statement said. The idea that her money could have gone toward settlements is especially loaded, considering that Benson, estimated by Forbes to be worth $3.2 billion, has accepted millions in public cash to support her team—including the $90 million in state funding currently being used to renovate the Superdome.

The Bensons’ foundation contributed more than $62 million to the archdiocese and other Catholic institutions from 2007 to ’18, according to publicly available tax forms, though how that money was used is not specified.

In the first few months of 2019, shortly after the list’s release, Benson also made a $5 million gift to Jesuit High, which the all-boys private school said was used to renovate its athletic facilities. Tom Benson graduated from Jesuit’s rival high school, but Gayle said her connection to Jesuit was through Bensel and Lauscha, who are alums. “They have both been incredibly loyal to my late husband,” Benson said in a speech announcing the donation.

Just two weeks ago, in early June, a subpoena was issued to Jesuit and its former president, Father Christopher Fronk, requesting all of their communications with any Saints personnel, including Benson, Bensel and Lauscha, “pertaining in any way to the issue of sexual abuse of minors.” The subpoena stems from an active case in which a plaintiff, called Jayson Doe and represented by Trahant and his cocounsels, says he was raped in 1978 at age 13 by a Jesuit employee who helped him gain admission to the school. The lawyers asked for communications after Sept. 19, 2018—the same date The Advocate published an article revealing that the school had made undisclosed settlements with sexual abuse survivors (in the article, Jesuit said it could not comment on specific cases, but Fronk sent a letter to the school’s parents and alumni acknowledging the abuse). In the Jayson Doe complaint, the attorneys also alleged that millions of dollars of settlements were quietly paid with money from Jesuit benefactors that had been designated for other purposes.

This new subpoena, and the Saints’ link to Jesuit, is notable, because the same group of attorneys wrote in a filing in the Brignac–John Doe suit that the Saints emails showed the team had “independently reached out (in a seemingly unsolicited manner) to the president of a local Catholic high school that also has been sued multiple times for child rape.” The lawyers did not make clear to what purpose the Saints allegedly contacted the school, nor did they identify it by name. But sexual abuse at Jesuit was described in at least six suits filed against the school, the Church or the Jesuit order in 2019 (two have been settled), and appears to fit this description.

A Jesuit spokesperson declined to comment on the pending Jayson Doe suit, but said the Saints did not make any contact with the school related to the sexual abuse crisis, and reaffirmed Jesuit's stance that all donations received by the school are used for their intended purpose. Fronk stepped down in January; when reached by phone, he said, “I never heard from the Saints on this issue.” The first he heard of the Saints' having any involvement in the handling of the clergy abuse crisis, he added, “was when I read it in the newspaper.” Gulotta and the Saints did not reply to an inquiry about the subpoena.

***

The man in the Brees jersey at the SNAP demonstration was Richard Windmann, a self-described cradle-to-grave Catholic and Saints fan. He was also the survivor who came forward publicly in that September 2018 Advocate article exposing the abuse settlements at Jesuit. Windmann had shared his account of being sodomized as an adolescent there in the 1970s by Pete Modica, a janitor at the school. On one occasion, Windmann said, a priest masturbated while watching the abuse. Modica—the same employee Jayson Doe said raped him—died in 1993. Windmann says he settled his abuse claim with Jesuit several years ago.

In the days following the protest, Windmann’s phone buzzed intermittently with numbers he did not recognize.

“Don’t f--- with the Saints,” he says one caller told him, before hanging up.

Daunting as the path may be, Windmann and his fellow survivors felt they were making progress—until the Church’s May bankruptcy filing froze the email fight. “We will continue to seek the public release of the Saints emails,” Trahant, Denenea and Gisleson said in a statement.

In the meantime, leaders from SNAP have appealed to a different kind of higher power: the NFL. They sent a letter in late January to commissioner Roger Goodell making two asks: first, to penalize Benson and the Saints under the league’s personal conduct policy, which allows for a suspension or fine up to $500,000 for conduct detrimental to the league (they want the money to then be used to fund organizations working to prevent sexual abuse). Second, to show public support for abuse survivors. “We implore you to use the power of your office to show that the NFL is an ally to survivors instead of the adversary that the Saints have been,” they wrote. Bourgeois, who co-signed the letter, says Goodell has not responded. “That’s a slap in the face,” he says.

NFL spokesman Brian McCarthy said he was not aware of the SNAP letter, but that “our sympathies are with the victims.” He added that there is no current league investigation into the Saints: “We have been monitoring developments, but will continue to respect the judicial process.”

There is one way the emails could be released: with the Saints’ approval. Survivors have also called for Benson to create a fund to ensure those who have been abused have access to counseling and treatment. Amid the scrutiny, though, Benson and the Saints have held fast. She has said, in hindsight, she would aid the archdiocese again. “I am not going to be deterred in helping people in need,” she said in February. “We will always find the best way to unify and heal. That is who we are.”

Those words sound almost ironic to survivors, who believe that Benson, and by extension their beloved football team, have done just the opposite. “I felt betrayed,” Stonebreaker says. “They’re not helping when they are helping to hide the truth. That’s not helping. That’s culpability.”

Have a tip for Sports Illustrated? Please email us at tips@si.com.