Over the last year, as the world’s top 200-meter sprinter dealt with depression, he found that the medication he was taking limited his emotions—and created a possible impediment to his dream of gold.

Sign up for our free daily Olympics newsletter: Very Olympic Today. You'll catch up on the top stories, smaller events, things you may have missed while you were sleeping and links to the best writing from SI’s reporters on the ground in Tokyo.

Keisha Caine Bishop could see her oldest child was struggling when she visited him in Orlando last July, around the time he should have been getting ready to go to the Tokyo Olympics. Lyles usually has a neon face—big smiles, outsized expressions. It is the face of a man who believes he can run faster than anyone in the world, which might just be true. But Bishop says, “When he picked me up from the airport, there was no light in his eyes.”

She knew the signs of depression too well. Bishop remembers when Noah; his younger brother, Josephus; and younger sister, Abby, were little, and “just the thought of getting everybody in their car seats was overwhelming. I used to want to cry.” Now her oldest child “was irritable, very irritable, and everything was overwhelming to him. He couldn’t figure out how he was going to make it through the day.” She told Noah she wanted to take him to a professional.

Bishop had introduced her family to therapy years earlier. So when a doctor diagnosed Noah with clinical depression last summer and prescribed Zoloft, he knew he should not be ashamed or embarrassed. What he did not realize is that, for him, Zoloft was a performance-diminishing drug.

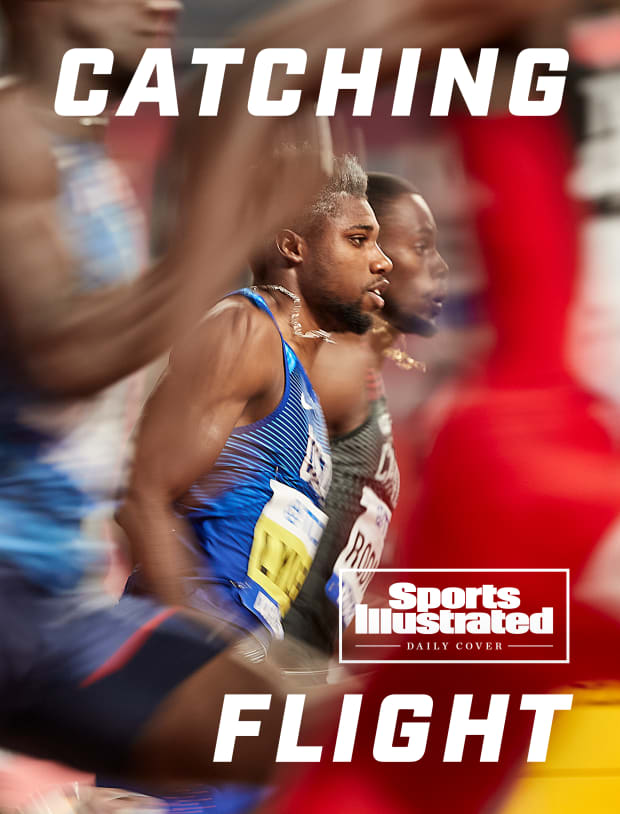

World-class sprints are pomp followed by lightning, like prizefights in which a first-round knockout is guaranteed. Crowds crackle as runners warm up and roar as they are introduced, and Lyles, the 2019 world champion in the 200-meter dash, loves every drip of it. Sometimes TV cameras go from lane to lane as names are called, and when they zoom in on Lyles, he has his back to them so he can make a big show of turning around—an introduction within an introduction. Zoloft (that’s the brand name; the actual drug is sertraline) does not affect everybody the same way. But the 23-year-old Lyles struggled to reach an emotional peak for races.

“The job of the medication was basically to neutralize my mood,” he says. “It got me out of the darker areas of my mind, but when I tried to reach higher than normal, it would always keep me buffered at what it considered a normal, calm behavior. It was very hard for me to get up to that excitement level. Say if 50% is normal. I’m stuck in between 40 to 60%, and I’m trying to get that to 90%.”

The 5' 11", 154-pound Lyles was not just competing against the world’s best sprinters. He was dealing with both depression and the effects of medication to treat it. His Olympic pursuit was no longer just about how fast he could run. It was a test of how quickly and thoroughly he could recapture his former self.

For the last three years, right after Christmas, Lyles’s family has visited a therapist together. Bishop calls it “a checkup from the neck up.” On Dec. 26, 2018, Noah, his siblings, his mom and his stepdad, Mark Bishop, each underwent evaluations for a psychological profile called the Birkman Signature Report. Noah’s report provides a window into the man who could be the face of the U.S. men’s track team this summer. It also sheds light on why he struggled so much in 2020.

Noah’s artistic interest came in at 99% and his musical interest at 85%, far surpassing his scientific (44%) and literary (24%) interests. His administrative interest (systems, order, reliability) was just 11%, which explains why, in recent years, he has lost his passport, his shoes, his wallet, his keys and his sister’s keys.

Most telling: His behaviors lean toward people instead of tasks. His needs include individual support, encouragement to express his feelings, and time for reflection.

To outsiders, Noah and Josephus (born one year apart) are easily grouped together—Josephus is also a world-class sprinter. They both made the unusual decision to turn pro out of T.C. Williams High in Alexandria, Va., and move to Orlando, where the family had spent Noah’s first eight years, to live and train. (Josephus, who suffered a torn hip flexor before the 2016 Olympic trials, ran a 20.28 in the 200 semifinal at this year’s trials in Eugene, Ore., and did not make the final.) But the family sees them less as profile subjects for the Track & Field News and more as the embodiments of their Birkman Reports.

Josephus, Abby and Mark are introverts, while Keisha and Noah are extroverts. (Keisha and Kevin Lyles, Noah and Josephus’s father, divorced in 2008, and the boys spent most of their childhood with her.) Noah and his mother are so much alike that their shared therapist once told Keisha: “Sometimes, when I talk to Noah, I’m like, ‘Didn’t I already do this session?’ ” Noah once asked Keisha and Mark to extend their stay in Los Angeles so he would not have to spend one night there alone, while Keisha says Josephus tells her, “Ma, it’s O.K. for you to visit, but you have to go after five days.”

Young Noah was so high-energy, with such a short attention span, that Keisha says, “If I would tell Abby and Josephus to go clean their room, [they] would go upstairs and clean their room. If I would tell Noah to go clean his room, he would run up the stairs and maybe do a couple of flips to get there, and then get in his room, come back down and then go, ‘What am I supposed to be doing?’ ”

The family accepts that these are behavioral traits, not personal rejections, and while they find the differences hilarious, they respect them. Although her boys share a house, Keisha talks to Noah every day and to Josephus twice a week.

The pandemic hit the family’s extroverts hard. Keisha went for walks every morning and afternoon in Pikesville, Md., and she made daily trips to the grocery store to buy fresh fruit just to keep herself grounded. Noah says the weeks when Florida shut down “weren’t very fun.” He was not a great candidate to get through the pandemic by sitting quietly with a stack of books. Keisha says, “My husband was O.K. He was like, ‘I don’t understand what the problem is.’ Me and Noah are over here having nightmares.”

Noah barely missed out on qualifying for the 2016 Olympics in the 200 right after his senior year of high school, and COVID‑19 put his Olympic aspirations on hold again. Like many during the pandemic, he found himself focused on the murder of George Floyd, the shootings of Ahmaud Arbery and Jacob Blake, the open wound in a closed nation.

Noah is a people person who couldn’t interact with many people, consuming tragic news through the glass wall of modern technology, which allows us to observe everything but touch nothing. “You saw more and more of America’s dirty side throughout the year,” Noah says. “It was harder to handle that than it was to handle everything else.”

Lyles says he was not surprised by reports of police brutality, just saddened. He had already accepted that he was competing for his country despite its flaws. Still, he believes that these tragedies were the primary trigger for his depression.

What am I supposed to be doing? Olympians have short careers and get an outsized portion of their income from endorsements. Sponsors traditionally prefer political neutrality. Lyles weighed that and decided to publicly support Black Lives Matter anyway. Before winning a 200-meter race in Monaco, he put on a black fingerless glove and raised his fist. He did it again before the 100 finals in Eugene.

Despite that victory, Lyles heard track insiders question his performance in the year leading up to the Olympics. He wanted to do the Usain Bolt double: win both the 100 and 200. Lyles’s ability to sustain peak speed longer than rivals has helped him rank No. 1 in the world in the 200 since March 2019, and at the ’19 Shanghai Diamond League, he took the 100 in a Bolt-like 9.86. He clearly has double-gold talent, but he hadn’t dominated either event as some had expected.

In May, Lyles responded to the doubters with a comic riff: “Dang, I didn’t know, running 10 flat [in the 100], and 19.90 [in the 200] was a bad year. I’m sorry I spoiled y’all with such greatness! I’m sorry I’m not dropping 9.7 on you guys. I’m sorry! I’m sorry! Apparently, I’m in the wrong! So you tell me what I need to do.” He laughed. He believed, all along, that the time that matters cannot be measured in tenths of a second, but on a calendar: He just needed to peak by the Olympic trials, then again in August at the Games.

First came the trials. He finished seventh in the 100 final, running 10.05. Lyles acknowledged the disappointment but promised that his 200 would be “disgusting,” and it was—he ran a 19.74 in the final, the best time in the world this year. If he is chosen for the 4 × 100 relay team, he will be favored to win two golds in Tokyo. He had found a way to excel while maintaining his mental health. He had already discovered ways to excel while searching for his physical health.

Sprinting is Earth’s most universal athletic competition—pretty much every person in the world has tried running as fast as they can. Olympic sprints, then, are the sporting testament to American exceptionalism: In the 100 and the 200, U.S. men have won 33 of 55 gold medals.

From toddlerhood, Noah was both a natural and unlikely candidate to join that tradition. Both of his parents were sprinters at Seton Hall, and Noah had a talent and a passion for the sport.

What he could not do very well was breathe. He was diagnosed with reactive airway disease at 5 years old. He would need a nebulizer every few hours, and frequently he couldn’t stop coughing long enough to eat.

“We took him to the hospital, and he said, ‘Mom, can you please tell the doctor to please help me stop coughing?’ ” Keisha recalls. “And it just broke my heart. We spent a lot of nights when he was little . . . I would just sit up and hold him all night, so that he could breathe long enough to go to sleep.”

Keisha homeschooled the boys; Noah would have missed too much class otherwise. At age 7 he had an adenoidectomy and a tonsillectomy. In hospitals, and on days when his asthma kept him from playing with other kids, he developed an interest in art. He still spends much of his free time painting.

Keisha says his condition had another, subtler effect: “The asthma taught him to appreciate being healthy.” Before one race in the past year, when an allergy attack affected his lungs and caused a barking cough that kept him up for three straight nights, he thought, “This is only a little fraction of what it was like when I was a kid.”

Being healthy meant running, but it also meant having the social interaction he craved. Because they are so similar, Keisha understood her oldest child implicitly. When Keisha left Seton Hall, where she was a 10-time All-America, she had a shot at the 1996 U.S. Olympic team, but she says shortly before the trials that year, “I just kind of had this epiphany that I didn’t want to do this anymore. I didn’t know enough about myself back then. But now I realize that I missed the team aspect of the sport. Because when you run track professionally, the entire team aspect is gone.”

When Noah and Josephus turned pro and signed an eight-year contract with Adidas, Keisha decided the family would be their team. She travels to see them whenever she can, and when Noah went to Europe for a race, she flew over and hand-delivered to him a Yeti cooler full of his favorite home-cooked foods: lasagna, baked chicken, macaroni and cheese.

Being an extrovert is not a prerequisite for an elite sprinter. Josephus is proof. But Noah thrives on his sport’s excitement. Earlier this spring he said of no-crowd racing, “It’s not fun to run with no people.” As the pandemic wore on him, he and his mom decided they would build a big house where everybody in the family could live. One mortgage, one roof. They talked about it extensively and in great detail. They would have wings for each family member and share a kitchen.

“We were so excited,” Keisha says. “We had this whole plan.”

She busts out laughing and adds, “But nobody else in our family wants to do it!”

As his country started to return to its old bustling self, Lyles decided he was ready to do the same. Getting off antidepressants can be scary and dangerous and isn’t right for everyone. But this spring Lyles and his doctors felt he was doing well enough to try.

“I needed to get back to that excited feeling,” he says.

Asked what has changed since he has gone off Zoloft, he deadpans, “Well, now I feel emotions.” In April he seemed like his old self again. Before a race at the USATF Golden Games in early May, he sensed something inside him he had not felt in years.

“I was just like, Oh my gosh, I think I feel nervous to run,” Lyles recalls. “And my coach [Lance Brauman] said, ‘You do?’ I was like, Yeah! I haven’t felt this in like four years. . . . It’s kind of nice! I kind of like it!”

He says he welcomes the nerves “because then I get to conquer my fear again. [I’m] kind of combining that childhood feeling with the adult knowledge of what you’re doing. . . .

“Even having those jitters back, it gets me more excited to run again,” he says. “I haven’t felt those in a long time, and I miss them. Let’s get back to that point where I’m so confident again that I don’t have to worry about who I step in a race with. I can just go out there and run and be free.”

The year 2020 changed Lyles and the country he represents. Even his high school had to change its name to Alexandria City High; T.C. Williams was a segregationist. It will take years to sort this all out. But he has started to feel that the Noah Lyles who shows up in Tokyo will be the one he wants to be.

More Olympics Coverage:

• The Games Go On—With a New Purpose

• Meet Team USA Athletes Competing in Tokyo

• Previewing Every Sport in the Olympics