The iconic show’s reboot sent me down the perfect rabbit hole during the MLB lockout. Here’s what I found.

The audio was distinctive enough to register for me instantly. It was only a scrap of background noise—the kind of sound that exists to be ignored—but the cadence was so particular, so familiar, that I couldn’t help but listen:

“With two on and two outs, runners at the corners, Gentry looks in for the sign, and the pitch—and that one is low. Ball two. He missed that one, and Baker had to pull it out of the dirt,” says the play-by-play announcer. “He did a great job of blocking the plate so that pitch didn’t get away from him,” replies the color analyst.

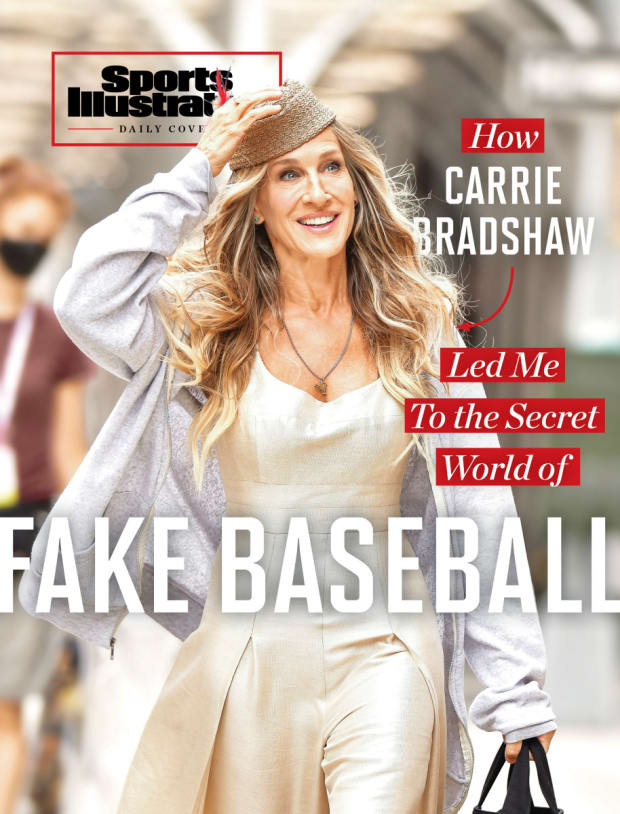

It was, of course, a baseball broadcast—in the middle of the Sex and the City revival series, And Just Like That…, on HBO. In the episode, which was released Jan. 20, the game is playing on a television when Miranda (Cynthia Nixon) enters the living room for a serious discussion with her husband, Steve (David Eigenberg). Almost immediately, Miranda asks him to turn it off, and the baseball audio disappears after just a few seconds. None of which is unusual: Lots of shows and movies include snippets of fake sports broadcasts as background noise. Yet this one had sounded conspicuously real. Instead of simply rattling off a score, the broadcast had included just the right level of specificity, all the textured banality of a random at bat. There seemed to be a whole booth involved instead of a lone announcer. And the rhythm was dead on—clearly, indubitably baseball. It was hard to imagine that the clip was fake. With all that attention to detail for just a few seconds of background sound? No way. Yet it was just as hard to imagine that the clip was real. With a cursory sweep of Baseball Reference pulling up no box scores that fit, not to mention the idea that the Sex and the City revival, of all programs, had invested in jumping through the necessary hoops to license big league footage for such a tiny moment? No way.

It was, in other words, a perfect mystery for a baseball writer during a lockout.

James Devaney/GC Images/Getty Images

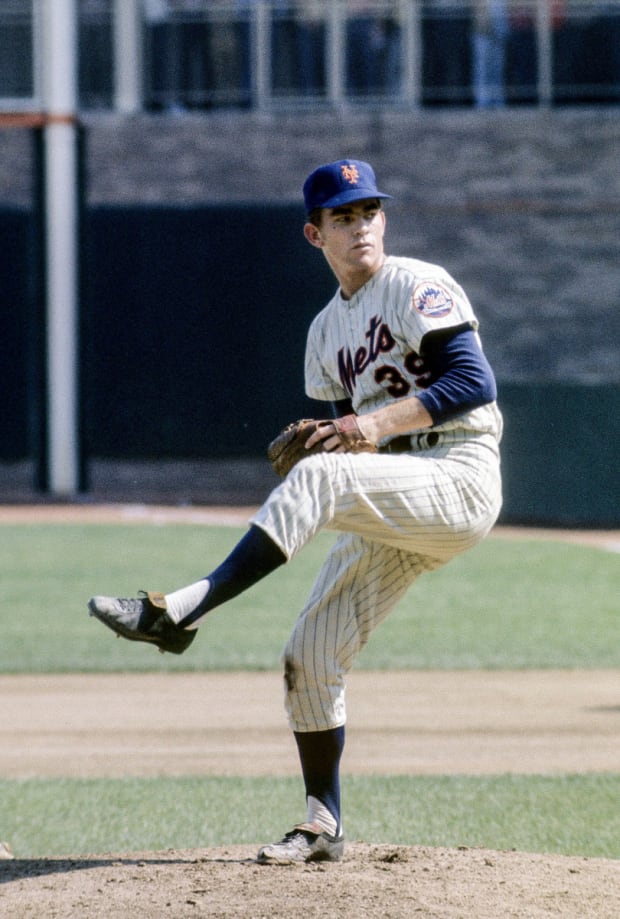

If the game was a real one from MLB, it shouldn’t have been hard to find. All the information was there: The pitcher was Gentry, the catcher was Baker and there were two outs with runners at the corners. (A close listen to the tail end of the clip, right before the television turned off, seemed to yield additional references to the fact that it was the eighth inning, with a score of 2–0 and teams from New York and Atlanta—but crosstalk with the actual characters in the scene made it hard to tell for sure.) Right away, I had a guess: Might the pitcher be Gary Gentry of the late 1960s and early ’70s? A classic Mets game would have been a perfect fit. Steve is from Queens, after all, and given that his wife was entering the room to say that she felt she’d moved on while he was letting the future pass him by … what could be more fitting than him reliving the glory days of the ’69 Mets’ run to the World Series?

Alas. Gentry never shared the roster with a “Baker” in his four seasons with the Mets. He was later teammates with Dusty Baker with the Braves, where he finished his career, but Baker never appeared at catcher. If the catcher here was indeed “Baker”—and the audio seemed quite clear that it was—the pitcher couldn’t be Gary Gentry.

That left three other MLB players named Gentry. But none of them fit. Outfielder Craig Gentry made one career pitching appearance in 2012, and while it did take place in the eighth inning, there had been no sign of a “Baker.” Rufe Gentry was a pitcher for the Tigers in the 1940s—but he never shared a roster with a player named Baker, and besides, the audio in question didn’t sound like an old-timey radio broadcast. Finally, there was Rufe’s brother, Harvey Gentry, who made a handful appearances as a pinch hitter for the New York Giants. It couldn’t be any of them. Which meant it wasn’t from MLB.

Then: a snippet of audio ripped from a broadcast of a minor league game? A college game? A fake game made for the show that happened to seem like an oddly suitable nod to the ’69 Mets? Or a fake game from some other context? “Baker,” after all, is one of the names in the sample lineup that MLB uses for examples in its rulebook. … But that lineup, which fills the nine spots with names that start with the first nine letters of the alphabet, uses “George” for G instead of “Gentry.”

It seemed like it was time to go straight to the source. I reached out to one of the production sound mixers listed in the credits of the show—surely, I thought, this would yield my answer. How much of a process could there possibly have been in getting this tiny scrap of sound, one pitch, not even one at bat, in the background of one scene?

I would soon learn that I was horribly naive on that point.

The sound mixer confirmed that the baseball audio was not a real game. It had been added in postproduction by a “loop group,” a unit responsible for recording the background noise in a show or a film, all of which is inserted later. Any snippet of chatter you hear from passersby in a scene, any radio program that a character has on in the background, any crosstalk or laughter or side conversation? That’s usually handled by a loop group. Their whole job is putting together that background audio—and, yes, that often includes fake sports broadcasts. But as for who the voice actors in that group for And Just Like That… actually were … well, the sound mixer wasn’t sure, and neither was one of the producers. The contract process for loop groups can be quite particular and sometimes even secretive, depending on the network and the gig. (Just look at a headline like “‘The Mafia of the Acting World’: Hollywood’s Secret Loop Groups” from The Hollywood Reporter.) In this case, postproduction had finished for the series—“everyone is scattered to the wind,” as the producer said—and there was no obvious answer as to who would know the provenance of this specific bit of background audio.

I did my best not to sound freakishly obsessive about the whole thing as we went back and forth: Do you know anyone who would know? Finally, I got the one-line email I deserved:

“Sorry Emma. The trail is officially dead.”

It was a very gracious suggestion that a normal person should let this go. I took it as a suggestion for me to spend the rest of my afternoon looking up how loop groups were acknowledged in television credits—when they were acknowledged at all—and trying to figure out if there was anything in the credits of this episode that might match.

And there was. Two people, Dann Fink and Bruce Winant, had been credited with “additional vocal casting,” a term sometimes used for looping background audio. I took a chance, reached out and found just what I had been looking for.

Focus on Sport/Getty Images

Fink and Winant were indeed the voices behind the baseball game. (Fink was the color man, Winant, the play-by-play.) But they weren’t brought in specifically for that: It was just one part of the work involved with doing all of the background sound for the series.

Take, for instance, something like a restaurant scene that occurred earlier in this episode of And Just Like That…. When the cameras are rolling, everyone is quiet except for the principal actors, so their dialogue can be easily heard. There might be other people visible as waiters and hostesses and fellow diners—but they’re silent while shooting is happening. All the background sounds you’ll hear from them when you actually watch the show? The chattering and laughing and silverware clattering? That comes in courtesy of the loopers.

Winant and Fink will receive a cut of the episode and be told how many voice actors their loop group can bring on for the project. (In this case: six.) And they jump into creating the sonic context of the show—recording all the material that will later get layered in to make the background come alive.

“We’ll then put voice to everyone else in the room,” Winant explains, using the restaurant scene as an example. “So we’ll be the waiters. We’ll be that table directly behind the principals ordering dinner. We’ll be the hostess helping them in.”

Multiply that by every scene where there might be some background noise. (Which is to say: Multiply it by almost every scene.) The work has to fit its context; if a show features a scene in a hedge fund, for example, the loop group will make sure the background dialogue it records uses some financial lingo, and the same for a hospital scene and medical jargon. But where it really gets fun is putting together something like a fake sports broadcast.

MediaPunch/Bauer-Griffin/GC Images

A show or a film can license footage from the league in question. Yet it’s often easier or cheaper not to (or to license only the video and not the audio). But a good loop group will try to fit even the most specific requirements to create the necessary sound. For instance, Winant and Fink have been working on Kevin Bacon’s Showtime series, City on a Hill, which is set in 1990s Boston—so when baseball is heard on the radio in the background, they had to audition voice actors who can pass well enough for Joe Castiglione. Or when they worked on the FX program Fosse/Verdon, they were asked to re-create the Mets game from a specific night in ’81, which meant combing through the box score to make sure they had the right pitcher in at the right time.

But sometimes it’s all left a little more open, which leads to something like the game broadcast from And Just Like That…. If the producers don’t need a specific accent or sound, Winant likes to do his own work on the play-by-play: He has a voice made for broadcasting, smooth and pleasant, and he’s a sports fan, so the rhythms are ingrained. (Though some are easier than others. One show recently had him re-create a Bruins-Penguins game, and “I’m not a hockey fanatic, so I had to do research on that one,” he says.) He starts by making note of whatever details the producers want him to include—this ballgame, for instance, had to feature a team from New York. And then he pulls up a game, any one that fits, and uses it as inspiration to think about how he would call it himself.

“I’ll listen to that game, and I’ll transcribe it, but not directly,” Winant says. “In other words, I’ll listen to it to get the flavor.”

There are a few ground rules he has to play by. Unless the show has gotten permission to use a club name, Winant sticks to calling teams by their cities, and he uses only last names to avoid directly naming a specific player. As for picking those names? He goes with whatever comes to mind. Which helps when your mind has plenty of baseball players in it to begin with—and in this case, yes, “Baker” did have him thinking of Dusty, even though he knew he was sketching out an imaginary catcher.

“I’m just making up names that sound like baseball players,” says Winant, who has been in the looping business for 30 years. “Sometimes I’m thinking of old players. I just want to make sure that I don’t say Mantle or Koufax or something like that.”

(Once, he did think about putting in Stargell, just to see how it would play. He ultimately decided against it—“too specific.”)

After he has his names and the flavor of the action in mind, he makes the call, trying to keep it as realistic as possible. The pacing is crucial—it has to sound like a baseball game, matching the natural, leisurely flow of the action. It’s what differentiates something like the work he did here, with its details of the pitcher leaning in to see the sign and the catcher blocking the ball in the dirt, from an obvious fake like “he’s-up-he-swings-he-misses.” It might be just a tiny moment in the show. It is, by design, meant to fade into the background. If the work is done well, chances are that no one notices it at all. And yet there’s still an important guiding force here—one both of principle and of style.

Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated

“It’s fun to put those together,” Winant says, “because it’s like, Oh, this is the kind of game I’d like to see.”

When I first heard the game, in the moment, I thought only that I had to know where it came from. But after figuring out the answer? I’d like to see this game, too.

More From Emma Baccellieri:

• Why Crypto Invaded Sports

• Don’t Be Silly. This Isn’t Rob Manfred’s Fault, Says Rob Manfred.

• Solidarity and Betrayal: Inside Baseball’s First Major Labor War