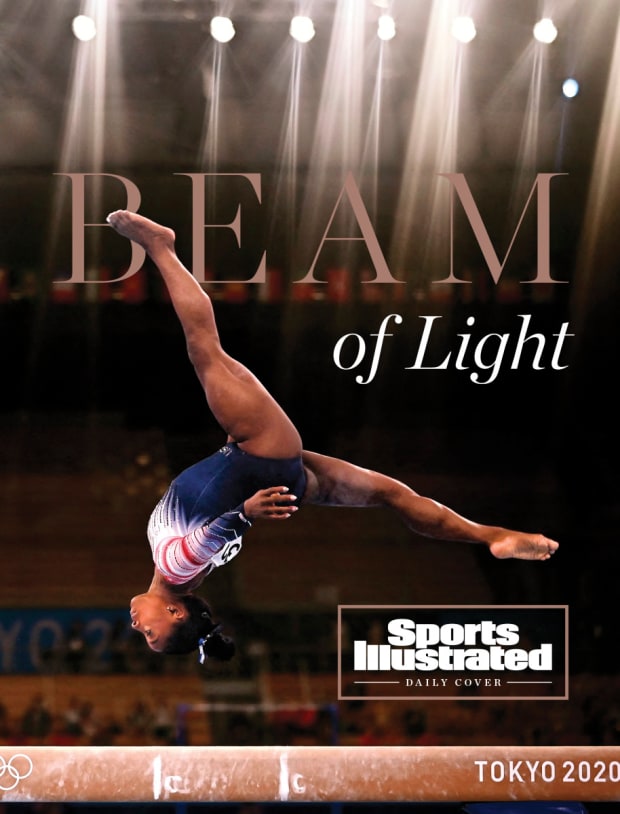

A week ago, a case of the twisties threatened her elite gymnastics career. On Tuesday, the 24-year-old returned to compete on the beam—for a medal, but most importantly, for herself.

For the first time all day, Simone Biles stumbled. Not on her routine, but over her words.

“There’s a lot of relief, obviously,” she said. “There’s—I don’t know. I don’t really know how I’m feeling right now.”

She barely remembered how she got here, standing in front of a microphone, with the most meaningful bronze medal of her life draped around her neck. She was not always sure what day it was. “I get so confused, because back home it’s 14 hours behind,” she said.

A week ago she thought she might never compete as an elite gymnast again. She suddenly developed a case of the twisties, a sort of gymnastics yips that leaves its sufferers lost in the air. The twisties are mentally infuriating and physically dangerous—they put gymnasts at risk of paralysis or death.

After a disastrous vault in the team competition one week earlier, Biles had pulled herself mid-meet. “I can’t do this,” she told her coach, Cecile Landi. Her score had already knocked the team out of contention for a gold medal, but without her, it held on for silver. Over the following days, she withdrew from one individual competition after another. But all along, she hoped she might be able to compete in the final event: the balance beam. She could adjust her routine so she performed only skills she could complete safely.

On Tuesday evening, she smiled as she approached the beam. She waved to the judges. As a small crowd of journalists, other athletes and officials looked on, rapt, she flipped and danced—but never twisted—her way through her routine.

As she waited for her score, the public-address announcer tried to run through her credentials. But how to sum up the greatest of all time? Biles, 24, now has 32 Olympic and world medals. She has four skills named after her. Before these Olympics, her opponents openly admitted they were competing for silver. The PA announcer finally settled on “highly decorated.”

Biles’s score finally arrived: 14.000, low for her any other week. Biles nodded. It put her in second.

But she still had to wait for five more gymnasts to compete. The first three finished behind her. She had to beat at least one of the last two for a medal, and China’s Guan Chenchen, who qualified in first place, was lurking as the last to take the stage. When Brazil’s Flavia Saraiva, competing seventh, grabbed the beam and took herself out of contention, Landi enveloped Biles in a hug.

Biles’s work ethic and competitive joy are special. But what has really set her apart her whole life, even when she was a grade-schooler bouncing on her family’s trampoline, was her air awareness. She always seemed to know where she was. Until this week. Her best friend, Rachel Moore, told her, “It’s almost like your superpowers were stripped away from you.”

As the U.S. team arrived in Tokyo, Biles seemed to be in good spirits. “Girl, I am ready,” she told Moore. But on the day of qualifications, her tone was different. “Rachel, I am so nervous,” she said.

Moore said, “I’ve never seen Simone nervous before.”

That afternoon, the world saw it, too. On her first vault, Biles landed askew and stepped off the mat. On the beam, she took three steps on her dismount, a mistake high-performance director Tom Forster said he had never seen her make. On the floor, she bounced out of bounds and off the carpet. She still finished in first and qualified for the finals in every event, and the team finished in second, but it was a disappointing performance. The gymnasts declined to speak to the media afterward. “The errors we made, I think, are mental,” Forster said.

The public still did not grasp what was happening. It seemed like a bad day. Everywhere Biles goes, an assumption of greatness follows her. It was hard to see that the team's struggles would foretell her own.

The next day, Biles stumbled through practice. “I literally couldn't even get my toes on the bar,” she said. Her routine on the beam was O.K., but as she tumbled on the floor, she felt something break inside her.

“The wires just snapped,” she said. “Things were not connecting, and I don't know what went wrong.”

She posted on Instagram that night: “It wasn’t an easy day or my best but I got through it. I truly do feel like I have the weight of the world on my shoulders at times. I know I brush it off and make it seem like pressure doesn’t affect me but damn sometimes it’s hard hahaha! The Olympics is no joke!” This did not set off many public alarms, either.

Heading into the team final, she hoped she would find her way again. The U.S. began on vault, one of Biles’s strongest events. She has one skill named for her, and she had hoped to add another this week by landing the Yurchenko double pike.

Her hopes diminished quickly. During her practice vault, she lost herself in the air, completing only one and a half twists before plummeting to the mat. She had not done such a simple vault since she was a preteen. In the competition, she did it again. Her score flashed on the screen: 13.766, the worst mark on the vault of her senior career.

She immediately told her coaches that she had to withdraw. They assured her that she would be fine. “No,” she said. “I know I’m going to be fine, but I can’t risk the medal for the team, so I need to call it.”

She also knew she might not be fine right away. The finals were about to begin. Only two gymnasts per country can qualify for them, and, if Biles competed, two of her teammates would not: Jade Carey in the all-around and MyKayla Skinner in the vault. Carey was scheduled to stay in Tokyo to compete on the floor and vault, but Skinner was due to fly to Arizona the next day. During the team final, Biles asked Landi to make sure Skinner did not leave. Landi texted Skinner’s coach, Lisa Spini. Sitting in the stands at the Ariake Gymnastics Center, they went to United’s website and changed their flights.

Biles spent the rest of the evening cheering for her teammates and fetching them chalk as they competed without her. From the floor, she shadowed Jordan Chiles’s beam routine, hitting all the landings. For the first time all week, Biles looked comfortable.

Afterward, she alternated between giggles and tears. She poked fun at herself—”Girl, I did not choose to do a one and a half!” she told an interviewer—but turned somber when she considered her situation.

“I just don’t trust myself as much as I used to,” she said. “I don’t know if it’s age, but I'm a little bit more nervous when I do gymnastics. I feel like I’m also not having as much fun, and I know that”—she began to cry—"this Olympic Games I wanted to do it for myself, and I was still doing it for other people, so that just hurts my heart badly, that doing what I love has been taken away.”

On Wednesday, she withdrew from Thursday’s individual all-around competition. On Thursday, she posted videos to Instagram of herself landing on her back in a foam pit as she tried to dismount from the bars. “Literally cannot tell up from down,” she wrote. On Friday, she withdrew from Sunday’s vault and uneven bars finals. On Saturday, she withdrew from Monday’s floor exercise final.

She tried to stay off social media, moving the Twitter app to the last page of her phone, but she still noticed the criticism she was receiving. People called her a quitter. People said that she had let down her team and her country. People suggested that she might be off her ADHD medication because of Japan’s strict drug laws. It all drove her wild, how well these strangers thought they understood something even she did not understand. “Honestly, guys, I have not taken ADHD medication since 2017,” she said. “There are so many speculations.”

At times she seemed to spend more time crying than not. At one point, she learned that an aunt on her father’s side had died. And the gymnastics did not get easier. She left one practice early after, she said, “I had the biggest mental breakdown. Like, I could not breathe. And I was just like, ‘Not today.’” The whole time, though, Biles had been working on her beam routine. She scrapped her normal dismount, which incorporates a twist, and instead practiced a double pike, a flip so simple she had not done it since she was 12. But she began to feel stronger.

The words of friends and some strangers bolstered her. Fellow athletes came up to her in the Olympic Village to thank her for speaking up. She burst into tears in the Olympic store, touched by how much she seemed to mean to them. Moore told her, “I don’t think I’ve ever been more proud of you.” Biles had spent much of the past year trying to imagine a life without gymnastics. Now she began to believe she had value beyond her achievements.

She also met daily with doctors and spoke twice with a sport psychologist. On Monday night, after practice, she came to Ariake Gymnastics Center to see the FIG doctor. All week, he’d been asking her the same questions, trying to ascertain whether she was ready. All week, she’d said no. This time, she said yes.

Biles has still not conquered the twisties. She sees other gymnasts do double-doubles and “I want to puke,” she said. “I just cannot fathom how they’re doing it.” She succeeded Tuesday only because she did not have to twist. And she still does not know how—or whether—she will find a cure.

“My problem was why my body and my mind weren't in sync,” she said. “That's what I couldn't wrap my head around. Like, what happened? Was I overtired? Where did the wires not connect? And that was really hard, because it's like, I trained my whole life. I was physically ready. I was fine. And then this happens, and it's something that was so out of my control.”

She does not have answers to these questions. People around her believe that the pressure finally crushed her.

Her camp had concerns coming in that this would be a harder Olympics than the public realized, with no fans and enormous expectations, especially for someone like Biles, who feeds off the crowd. Before flying to Tokyo, Biles asked her boyfriend, Houston Texans safety Jonathan Owens, about playing in an empty Soldier Field in December. “Honestly,” he said, “It felt like practice.”

The atmosphere at these whole Olympics also had the energy of practice—but with the stakes of a legacy.

Biles has faced outsized expectations since she was a preteen whose routines were so stunning that judges halted meets so they could watch. But she has never had to do it alone. Her parents have attended every competition of her life until this one. At the U.S. Olympic Trials, her family and friends wore matching T-shirts—blue on the first night, red on the second—so she could find them in the seats. Her sister, Adria, usually screams so loudly for her that other fans turn to look. The last thing Biles does before she competes is look into the stands and find the people who love her.

In Tokyo, she looked into the stands and saw empty seats. Before she mounted the beam Tuesday, she closed her eyes. It was time to trust herself.

More Olympics Coverage:

• The Bronze Medal Beam Routine That Made Simone Biles Whole Again

• Former Gymnasts Left Paralyzed Are No Stranger to the Struggles Biles Faced

• Gabby Thomas Sets New Standard for Sprinters, On and Off the Track

• Caeleb Dressel's Picture-Perfect Tokyo Olympics