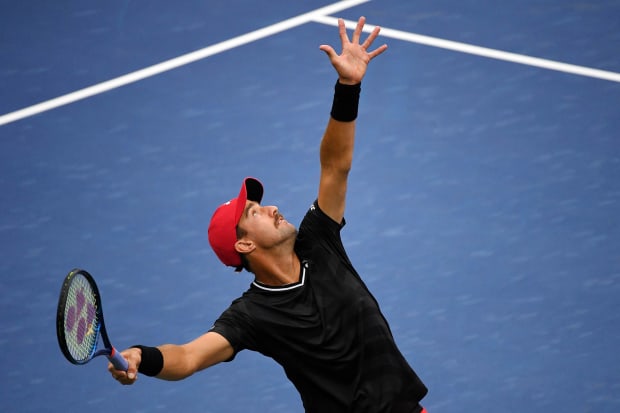

After suffering crippling anxiety after the death of his father, tennis pro Steve Johnson prioritized his mental health.

Steve Johnson was at home in Orange County, Calif., when everything started spinning. The tennis pro had just finished a grueling workout and assumed he was dizzy because he hadn’t eaten enough beforehand. A few minutes later, he started shaking while waiting in line at a bagel shop. Johnson ran outside and took a seat in his car, confused as to what his body was experiencing.

“I’m freaking out. My heart rate feels like it’s 200 miles per hour,” says Johnson, 31, iover the phone, recalling the incident that occurred in January 2018.

He reentered the shop, but the frightening symptoms returned. Johnson called his mother and fiancé and told them he felt like he was having a heart attack and needed to go to a hospital.

He later learned he had suffered an anxiety attack.

“Your mind plays tricks on you, feeling that it’s something worse than it is,” says Johnson. “That first one was definitely a foreign feeling.”

He was feeling a lot of pressure at the time after losing three of his first four matches to start the year. Most of all, he was still struggling to process the sudden death of his father, Steve Johnson Sr., who passed away due to a heart attack eight months earlier.

Johnson Sr. first put a racquet in his son’s hands when Stevie was two years old; the toddler used to run around the family yard swatting balloons and beach balls. As a boy, Stevie spent long days at his father’s tennis club, the Steve Johnson Tennis Academy, where he quickly became his father’s protégé, winning tournaments against kids a few years older than he was.

Johnson Sr. passed off the coaching reins when Stevie attended USC, but he was in the stands to watch his son win back-to-back NCAA men’s singles championships and finish his college career with 72 straight victories in 2012. Four years later, Johnson Sr. celebrated with his son in Nottingham, England, after Stevie won his first ATP title.

“I can remember that moment as clear as day,” says Johnson.

In May 2017, Stevie was at Los Angeles International Airport when he noticed an incoming call from his mother. He picked up nonchalantly, assuming she just wanted to wish him a safe flight. Instead, she had dreadful news: His father had died in his sleep at the age of 58.

Johnson was in shock, but he carried on with his season, traveling to Switzerland for the Geneva Open a week later, followed by Paris for the French Open. In an on-court interview after a second round victory over Borna Coric at Roland Garros, he couldn’t hold back his emotions. “I didn’t know that feeling was going to come out of me after that match,” he says.

Johnson struggled internally throughout the remainder of the season, but he put on a strong face and told everyone that he was doing all right.

“It’s not easy when you’re trying to portray something that is completely false with what you’re feeling on the inside,” says Johnson.

People close to him, in particular his mother Michelle, tried to persuade him to speak to a professional. Johnson thought he could figure things out on his own, and he didn’t believe therapy would work for him. But in 2018, the anxiety attacks began, including symptoms that were particularly difficult to deal with during matches.

“The whole ground shakes and the stadium is spinning,” says Johnson. “That’s definitely not a fun process to be going through while you’re out there competing.”

He became reclusive, shying away from restaurants and social engagements, and staying home as much as he could.

“I really wanted to be in my own comfort just in case,” he says. “I was always in fear of when the next one was going to come instead of trying to embrace the problem and deal with it.”

Eventually, Johnson gave in to his mother’s prodding and started seeing a psychologist. He had wallowed in self-pity for a long time, wondering why his father had to die at such a young age. Through treatment, he was able to change his outlook. He says that was when everything stopped snowballing and started to go in the right direction.

“The biggest thing was shifting that conversation in my own head to how fortunate I was to have a father who cared, who I loved, who I had a great relationship with, all these positive things that I was overlooking because I was more concerned with why did this happen to me,” says Johnson. “A huge part of my transition to healing was to shift those thoughts and those processes from negatives to positives.”

Though he’s found a way to work through his grief, Johnson still misses his father. His eyes often veer to a framed photo he keeps in his office of the two of them in Nottingham, embracing after his first ATP title. In December 2020, his wife Kendall gave birth to the couple’s first child, a baby girl named Emma. He wishes she had gotten the chance to meet her grandfather.

“I would give just about anything to have my dad here and be a part of this,” he says.

Today, Johnson deals with occasional anxiety attacks, but they occur less frequently than a few years ago. At the onset of an attack, he tries to calm his breathing as much as possible, and he focuses on putting his mind in his “happy place,” a term he admits sounds cliché. “I go through a checklist one by one and it just kind of calms you down and brings you back to neutral,” he says.

He knows how much he benefited from being vulnerable and seeking treatment, and he hopes his story might help someone who is suffering in silence.

“Trying to be that guy where you don’t want help or you don’t feel like you need help or you can get through this on your own, it doesn’t work,” says Johnson.