From technology to television to women's sports, nothing would ever be the same.

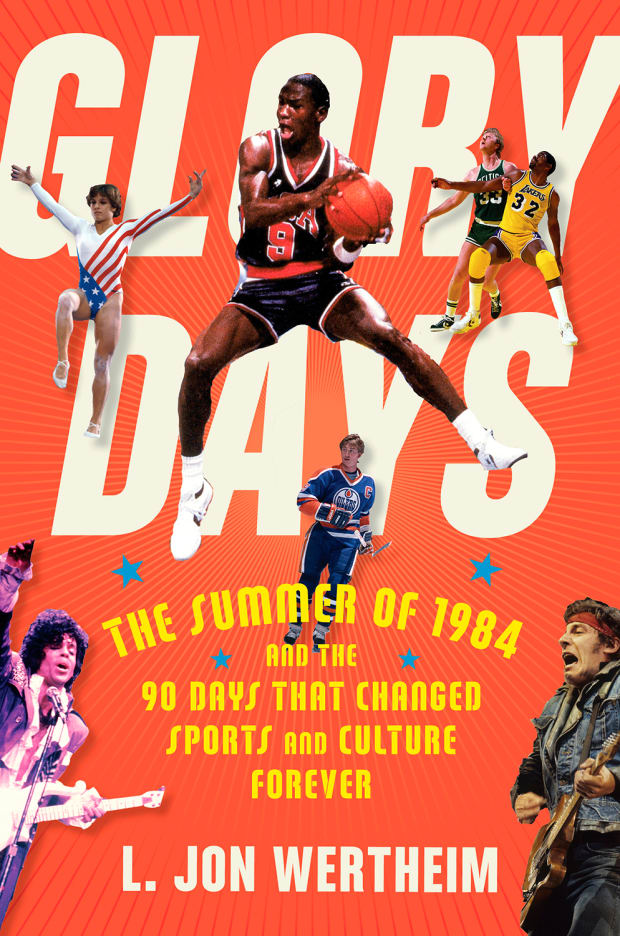

Excerpted from GLORY DAYS: The Summer of 1984 and the 90 Days That Changed Sports and Culture Forever, by L. Jon Wertheim. Copyright © 2021 by L. Jon Wertheim. Available June 15, 2021, from HMH Books & Media. Used by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

It had to be the least compelling competition in the history of the Olympic movement. The bid to host the Games often becomes a pitched battle, pitting one world capital against another world capital—often with significant capital changing hands.

But the derby to host the 1984 Summer Games came down to two disparate municipalities: Los Angeles and . . . Tehran.

Los Angeles was desperate to host, having submitted bids for the Summer Games in 1948, ’52, ’56, ’76 and ’80. When each of those was unsuccessful, L.A. still volunteered to serve as a “stand-by” if any scheduled host had to cancel unexpectedly. As for the Iranian bid, it was made when the Shah was still in power. When he was overthrown in ’79, triggering great civil unrest, the bid was withdrawn. So it was that Los Angeles didn’t win the right to host the ’84 Summer Olympics so much as the city got the Games by default.

Then again, at the time, the Olympic flame was flickering unsteadily. The Munich Olympics in 1972 were recalled foremost for the 11 Israeli athletes and coaches massacred by a group of Palestinian terrorists. The legacy of the ’76 Games in Montreal was not heroic athletic achievement but heroic expense. Games slated to cost $250 million carried a final price tag of $1.4 billion, and Canadians wouldn’t discharge this debt until the fall of 2006, 30 years after the closing ceremony. The United States was among the 65 countries boycotting the 1980 Games in Moscow, an incursion—however justified—of geopolitics into sports.

Some went so far as to predict that the 23rd Summer Games would mark the last Olympics ever held. On May 21, 1984, Newsweek posed an existential question on its cover: are the games dead?

Within three months, it was not only abundantly clear that the Games were very much alive, but when run efficiently, the Olympics could marry sports with media, technology and commerce and turn a profit. If some Games are recalled for singular feats and singular athletes, the ’84 vintage might be remembered best as an organizational success, heralding the coming Sports Industrial Complex.

To start, the 1984 Olympics offered a glimpse into the future of media and communications. When competitors and coaches checked into the athletes’ village at UCLA, they were handed assorted swag bags. (The one provided to all U.S. athletes from Levi Strauss contained 54 different articles of free attire.) The competitors were also given a password to an electronic messaging system (EMS) connecting more than 50,000 members of the “Olympic Family,” from the athletes themselves to media members to volunteers. Records would reveal that most people given these passwords never actually activated them, thereby missing their first email experience.

Before the Los Angeles Games, technology was a scarce commodity at the Olympics. At Montreal in 1976—the previous Summer Games held in North America—the distances of discus throws were determined with tape measures. Boxing scores were tabulated by hand. An army of messengers hand-delivered memos and sheets of information from venue to venue.

Organizers in L.A. were determined to prove that the intersection between technology and sports was, at least potentially, a busy one. Some of this was by necessity. With 23 sites spread across 4,000 square miles, information couldn’t be transported via messenger.

Buy Glory Days: The Summer of 1984 and the 90 Days That Changed Sports and Culture Forever

But this pivot to technology was also philosophical. A few hours south of Silicon Valley, Peter Ueberroth, president of the Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee, and his team were intent on showing off American innovation and the practical application thereof. As often as he had to explain that, no, he was not the Los Angeles Times’ star sports columnist by the same name, Jim Murray, vice president of technology for the committee, proudly announced, “We wanted to do some things that have never been done before.” The organizers estimated that the committee spent $50 million on technology.

Even before the Games started, it was hard not to notice the wires and cables and gadgets unfurled at the venues. As a press release breathlessly put it: “Personal computers help tabulate results quickly; electronic timers clock swimming and track races . . . mass spectrometers and gas chromatographs test athletes for banned substances and drugs; state-of-the-art pagers remind competitors of team meetings and event starting times; and sophisticated radio communications equipment carried by security personnel aid efforts to protect Olympic athletes.”

Sponsors helped defray the cost and set up the infrastructure. IBM provided monitors at the boxing venue. Motorola distributed pagers. Maybe most significantly, AT&T set up the EMS. The networks entailed 1,700 terminals and 7,000 paging devices connected by 300 miles of light-guided cables. “The Olympics EMS will be one of the largest area communications networks ever developed,” said Jack Scanlon, Western Electric vice president for processor and software systems.

“The scale of the system is Olympian in itself,” added Bob Ford, a spokesperson for AT&T Bell Laboratories. “Most of these people, especially the foreign athletes, have never even seen a computer before.”

Mark Houska, then a USC student on summer break, was a volunteer for the basketball events held at The Forum, where there were a half dozen terminals near the media seating. He recalls them going unused. You were going to leave your work area to check in at a computer terminal during the day? So you could get messages from someone you already worked with?

One of the television production assistants working for ABC Sports, Jay Bilas, an L.A. native, had finished his sophomore season at Duke. Given his interest in media—and given that he was the starting forward on his school’s basketball team—he was a natural for the position. Bilas was not, however, tech-savvy. During the training session for electronic messaging, Bilas casually shared his password with spirited colleagues. Later that day, female production assistants were surprised to receive strikingly personal messages from “Jay Bilas.”

When they weren’t hacking one another’s accounts, the production assistants gradually took to this instant electronic communication. They realized that they could send one another short messages, arrange meetup times and gossip, without worrying about remembering phone numbers or getting busy signals.

The few Olympic volunteers and media members who took the time to use these accounts realized another benefit. As the Games were unfolding, it was fun to send messages back and forth, firing off staccato burst observations, issuing predictions and making offhand remarks and cracking snarky jokes. In retrospect, they were using email to have a second-screen experience.

For decades, Pauley Pavilion had been most closely associated with giant men, most notably the UCLA basketball teams that won 10 national titles in 12 seasons under coach John Wooden. But on Aug. 3, 1984, Pauley belonged to a 4' 8" waif with size 3 feet, a 16-year-old who, as Los Angeles Times columnist Richard Hoffer put it, “restored pixie to our vocabulary.”

Mary Lou Retton of Fairmont, W.Va., something other than a gymnastics hotbed, was so transfixed by gymnastics as she watched Nadia Comaneci of Romania in the 1976 Olympics that she would sleep in a leotard. Within a few years she was being coached by Bela Karolyi, the austere Romanian who had trained Comaneci. Here Retton was, eight years later, herself in the Olympics, with a chance at gold, pitted against Comaneci’s heir apparent. Trailing Romania’s Ecaterina Szabo by five hundredths of a point in the women’s all-around, Retton headed to Karolyi. “You need a 10,” he told her flatly. She nodded, took a breath and executed a vault.

Already smiling before she landed flawlessly, Retton became the first U.S. woman gymnast ever to win the all-around gold. She also became, instantly, one of the figures most closely associated with the L.A. Olympics. This was in keeping with a theme that rang throughout the Games. In many respects, this was the Women’s Olympics, an event that would represent a hinge point for women’s sports.

In the mid-1980s, the sports public—fans, media, sponsors—still had an uneasy relationship with women’s sports. Title IX, then 12 years old, was supposed to have created equal opportunity for women, but for college administrators and athletic directors, it was a piece of federal legislation that went largely ignored. The number of broadcast windows and column inches devoted to women’s sports was vanishingly small. In 1984 the ratio of woman athletes participating in the Olympics hit a high of . . . 23.1%.

How could this be, that for every woman Olympic athlete there were three men? Fewer events, for one. Until 1960 women’s Olympic track races were never longer than 200 meters, with one notable exception. Women competed at 800 meters at the ’28 Olympics in Amsterdam. There, several runners collapsed from exhaustion. For decades, the International Olympic Committee (IOC)—overwhelmingly male, it scarcely needs mentioning—declined to expand competitive opportunities for women in events that were seen as (their word) unfeminine. By ’80 the longest women’s race was still only 1,500 meters.

But after a groundswell of protests from groups asserting that XX chromosomes did not preclude long-distance running, the International Amateur Athletic Federation, track’s international governing body, added both a 3,000-meter run and a marathon for women for these Olympics. The 3,000-meter race came wrapped in controversy.

Maybe the most anticipated event of the Games, the 3,000 meters pitted U.S. star Mary Decker against a young South African runner, Zola Budd. Decker had been named Sports Illustrated’s Sportswoman of the Year in ’83, when she won two thrilling races, the 1,500 and the 3,000 at the World Championships in Helsinki. South Africa was excluded from the Olympics because of its apartheid policies. But thanks to a hastily delivered passport, Budd was able to run for Great Britain.

This was billed as one of the Games’ great showdowns. But five minutes into the race Budd clipped the leg of her rival, sending Decker to the infield of the track in a fit of pain and a fit of rage. Thanks to the power of television, Decker’s expression—a cocktail of anguish, anger and agony—became perhaps the enduring image of the Games.

Like that, Decker’s Olympic ambitions had been squelched. Budd never won one, either. Though ahead in the race, after Decker’s fall, she relinquished her lead, as if weighted from guilt. She finished seventh. Budd was eventually exonerated—if she had tripped Decker, it was inadvertent—but was never again the same runner.

The marathon debuted at the first modern Games in 1896. But the first women’s marathon was run in Los Angeles. Joan Benoit, of Maine, won the race in 2:24.52, faster than 13 of the 20 men’s Olympic champions—and proof of women’s ability to run far longer than 800 meters. She said: “Once I passed through that tunnel [of the L.A. Coliseum, site of the final leg], I knew things would never be the same.”

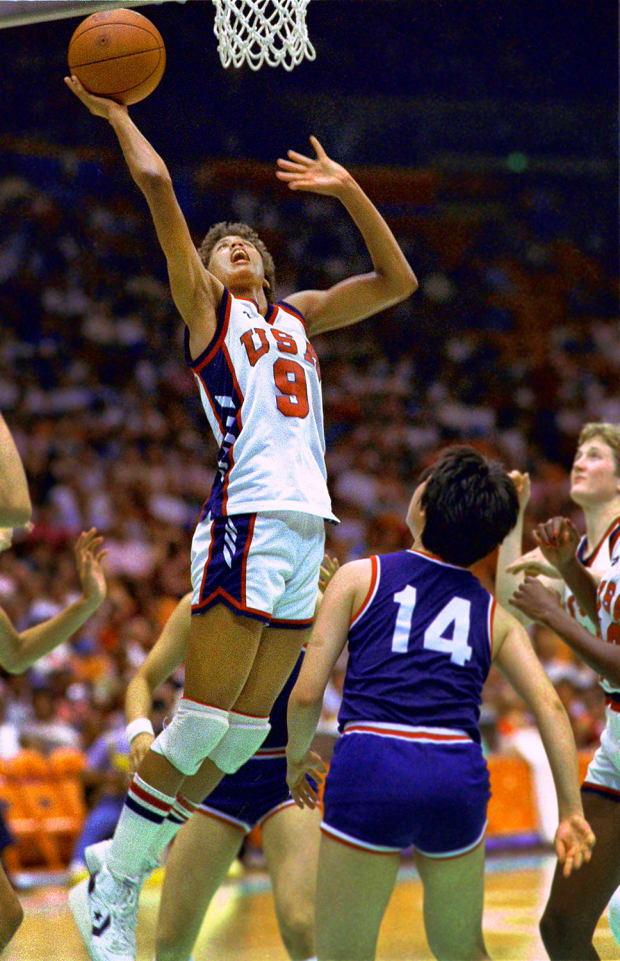

Meanwhile, when Nawal El Moutawakel of Morocco won the 400-meter hurdles, she became the first female gold medal winner from a Muslim country. (She also became the first Olympic champion from Morocco, man or woman.) Jackie Joyner, a converted UCLA basketball player, announced herself in the heptathlon. By the time the U.S. women’s basketball team had won gold and their coach, Pat Summitt, had been hoisted in the air, many wondered whether Cheryl Miller, the team’s star, was the most dominant player—woman or man—on the planet.

Joan Benoit was right. Things would never be the same. The percentage of female athletes would rise in each Olympics thereafter and is currently crowding 50%. Never mind a women’s Olympic marathon, eventually there would be women’s wrestling and boxing. Just as critically, the L.A. Olympics offered proof that sports fans—and, no less crucially, networks and sponsors—could, and would, warm to women in competition.

China’s first full Olympic delegation yielded 32 medals, including 15 golds. While sports had already been used as a crowbar to pry open diplomatic relations with China, the success of 1984 did something else: It changed China’s self-perception.

Susan Brownell, once a nationally ranked U.S. heptathlete, spent time in Beijing in the ’80s researching the anthropology of Chinese sport. She noted that Chinese athletes were often convinced that they were physically inferior to those of other ethnicities. This served, she told SI, “as the basis for self-fulfilling defeatism.”

Inasmuch as Chinese athletes were successful, they had excelled in “technique sports” such as riflery, archery and table tennis. Chen Weiqiang, the featherweight weightlifting champion, not only won gold but then held aloft the hand of the bronze medalist, who was from Taiwan. Li Ning won three golds in gymnastics in L.A. He would have won the all-around title, too, but for a careless mistake on the parallel bars when he bent his knee on an elementary move, a stutz to a handstand.

“The lid,” SI wrote, “has been torn off the cheerless world Mao made. Life is full of change, full of wonder, full of promise.”

Li Ning also used the 1984 Olympics to launch himself. After his gymnastics career, he founded what would become China’s largest sportswear company and one of the largest in the world. At its height in 2007, Li Ning Company Limited boasted 4,300 retail stores across the globe, a new commercial model for a blossoming economy. It was only fitting that he lit the torch during the opening ceremony of the ’08 Beijing Games.

If the 1984 Olympics expanded the scope of events, athletes and participating countries, these Games also opened the door to a new class of athletes: professionals. Before 1984, the Olympic soccer competition was open to only amateurs. This had the consequence of ensuring that the World Cup was the sport’s quadrennial tournament, open, as it was, to all players. It also meant that the Olympic format gave an advantage to players and teams representing Eastern Europe, where the entire concept of professionalism in sports scarcely existed.

For the 1984 Games, though, FIFA, soccer’s governing body, allowed professionals to compete, provided they had no prior World Cup experience. Given that Carl Lewis—the great star of the Games—had been flagrantly taking money from meet promoters and sponsors, this slight nod to professionalism seemed a small concession.

The tournament was a terrific success. France beat Brazil 2–0, in a spellbinding final played before 101,799 at the Rose Bowl, then the largest crowd to watch a soccer match in the U.S. Among those in attendance were dozens of IOC officials, who, apart from a gripping game, saw the potential for marketing dollars that came by a loosening of the amateurism rules.

The door ajar, within eight years the best professional players in the NBA—the Dream Team, which included Michael Jordan, Larry Bird and Magic Johnson—were the stars of the Barcelona Olympics. Two years after that, the U.S., having demonstrated an ability to support international soccer, hosted the 1994 World Cup. The final was played in the Rose Bowl. As was the decisive match of the historic 1999 Women’s World Cup.

The L.A. Olympics made for one of the most wondrous sports spectacles in history, a thundering success by any measure. The Games featured almost 7,000 athletes from 140 countries and awarded 688 total medals, in 221 events. The United States was the runaway winner, and unquestionably the biggest beneficiary of the Communist boycott. At the 1976 Montreal Games, U.S. athletes had won 94 medals, 34 of them gold. In ’84 with so many rivals absent, U.S. athletes won 174 medals, 83 of them gold. Yet there was little sense that the competition had been diluted. The gold medalists had competed better than anyone else in the competition, and fans seized on this, not on the absentees.

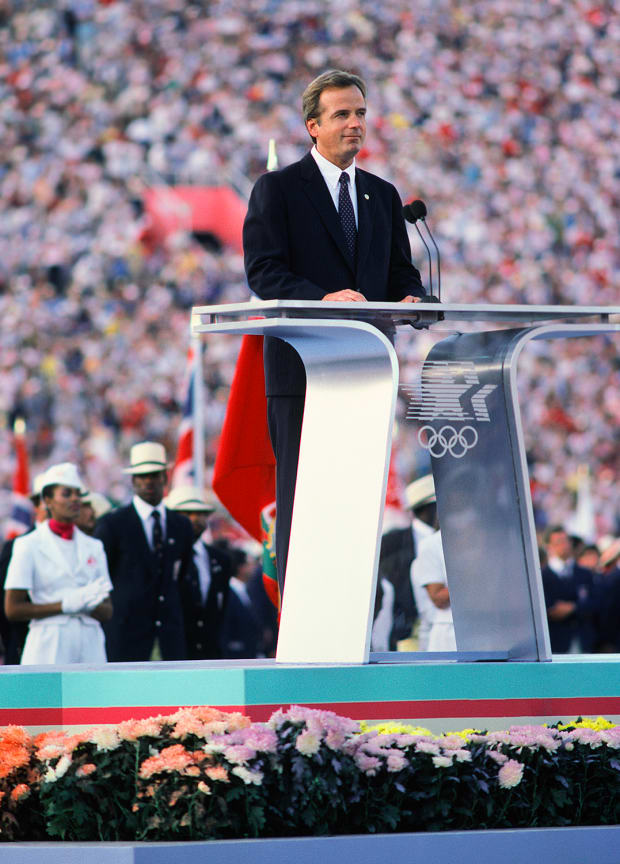

For all the new stars minted, none shone brighter than a 46-year-old man who wore loafers and a suit, ate entire meals while walking and survived on astonishingly little sleep. Before the Games had ended, the legend of Peter Ueberroth was already being recounted. With little budget and lots of challenges, and with military precision, L.A. had staged an Olympics that would become the new standard bearer. Beyond that, the alloy of sports and commerce and television would become a new blueprint. If the Olympics were now suddenly transformed from pure amateurism to a commercial enterprise, few seemed to mind.

Ticket sales came in at 5,797,823, a new record and nearly double the 3.2 million sold for the Montreal Games just eight years earlier. The TV ratings were astronomically high. More than 180 million Americans watched, making the 1984 Summer Olympics the most viewed event in television history. Ninety percent of all U.S. households had tuned in to the Games at some point. The sponsors that had committed roughly $150 million were thrilled with the association. Los Angeles was plump with civic pride and, by extension, the United States swelled with national pride.

During the Games’ closing ceremony, Ueberroth was saluted with a standing ovation from the crowd of 93,000 at the L.A. Coliseum. When the final balance sheets were prepared, the Games showed a profit of more than $250 million. Ueberroth was awarded a $475,000 bonus. He gave the money to charity.

Much of that profit was reinvested in sports programs and facilities in Los Angeles, through the LA84 Foundation. One of the projects included funding a series of after-school football teams in Compton. With his father serving a life sentence for a murder conviction, Caylin Moore availed himself to the program. He ended up going to TCU on a football scholarship and then becoming a Rhodes scholar. Nearby, a youth basketball program was also subsidized by the LA84 funds. One of the players taking advantage of this program: a hard-nosed guard named Russell Westbrook.

Also in Compton, LA84 supported a program called National Junior Tennis and Learning (NJTL), operated by the SoCal Tennis Association and designed to introduce the sport to kids from low-income neighborhoods. At NJTL events in Compton, volunteers watched, awestruck, as a pair of sisters in the program already showed more than a passing familiarity with tennis. One day, those sisters, Venus and Serena Williams, would—among many other achievements—win Olympic gold medals themselves.

• At the Indy 500, Roger Penske Is Still Running Circles Around Everyone

• The Mental Peril of This NBA Season

• Police Killed George Floyd. An MMA Fighter Punched Back