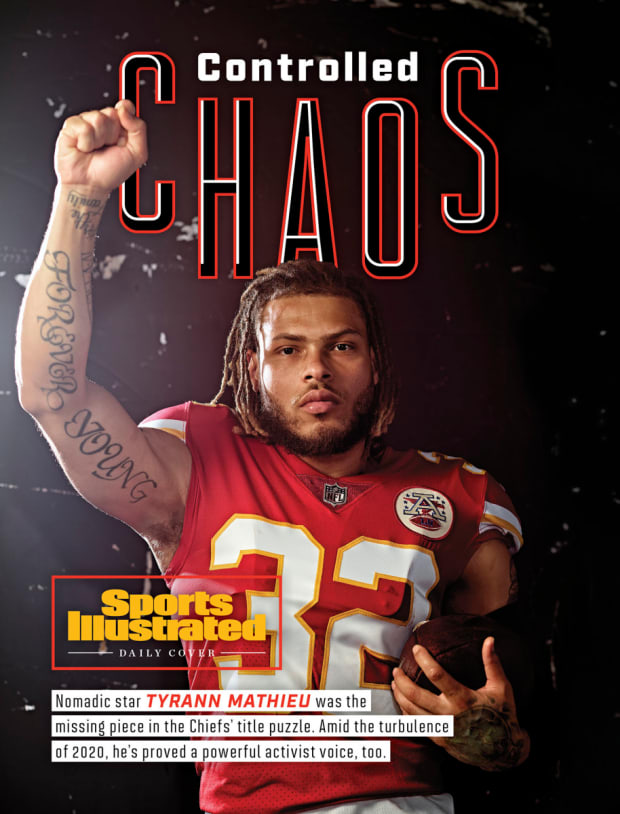

A nomadic star, Mathieu became the missing piece in the Chiefs’ Super Bowl puzzle. And amid the turbulence of a pandemic and social upheaval, he emerged as one of the most prominent voices among athlete activists.

Tyrann Mathieu looked up, past the red-and-gold confetti falling from the sky, and saw only stars, like the whole galaxy had been lit. He could hardly speak. He couldn’t move. The screaming fans, the euphoric teammates, the thuds of bass coming from the speakers—it all faded into a dreamlike silence. Mathieu asked himself a question he already knew the answer to: How in the world did I end up here?

On the night the Chiefs secured their first Super Bowl berth in half a century last January, he climbed atop a stage that had been wheeled onto the Arrowhead Stadium turf. He watched the family of late team founder Lamar Hunt accept the trophy that bears his name. The packed crowd stuck around through the freezing temperatures, the die-hards dancing and crying.

Mathieu spotted Brett Veach. The GM had signed him before the season and promised that the free-agent safety would elevate Kansas City after years of missteps and heartbreak (for both franchise and player) back to the pinnacle. Then Mathieu flashed back to absolute bottom. The funerals, the failed drug tests, the injuries. Had he really considered retirement? He drifted back, remembering how eventually he found himself, and then his chi, and then his voice, with help from a spiritual advisor, a naturopathic doctor and a mindfulness coach.

Finally, two teammates broke the trance. Tight end Travis Kelce grabbed Mathieu by the shoulders. Quarterback Patrick Mahomes jumped on his back. Both told the safety how much they appreciated him, how much he had meant to their playoff run, continuing in that night’s triumph over the Titans. Grips tightened. Tears welled. “It’s never a power struggle, never an ego thing,” Mathieu says. “We’re just some dudes who want to play ball, and at that moment we realized, in a sense, that we’re perfect for each other.”

Mahomes turned to some more teammates, pulling them close. “Remember what I told you when you signed?” he asked Mathieu, who nodded.

“Let’s start a dynasty.”

The stars had aligned around the safety, but Mathieu did not feel bliss, nerves or even accomplishment. Instead, he felt balance, peace. Through discomfort, he had discovered something unexpected: his own brand of Zen.

* * *

Today’s Tyrann Mathieu can hardly recognize previous iterations of himself. But to arrive here, as a cornerstone of a Super Bowl champion and a prominent voice for social justice, he had to first examine everything that went wrong. Only then could he make everything right.

He had to look back at his well-chroncled childhood in New Orleans—the father who went to prison for second-degree murder … the mother who dropped him on his grandparents’ doorstep … friend after friend after friend shot and killed. So deep were his feelings of abandonment, so low was his sense of self-worth, that even at St. Augustine, a majority-Black Catholic school that teaches grace and acceptance and empowerment, he clashed with those who tried to help him. “I saw a flickering of purpose,” says Del Lee-Collins, his high school coach and mentor. “But early on, our relationship was love-hate. He didn’t understand what I was trying to get out of him.”

Sure, Mathieu could run, jump, tackle and defend. And he did all that, mostly by channeling the rage that surged like electricity inside him. He could drop into an LSU football camp, ignore the chaos that spun his life in every direction, and show coach Les Miles that he deserved a scholarship, even at 5’ 9”. Miles could tell, though, that the young man looked upon himself through a funhouse mirror, his perception warped. Mathieu saw a singularly focused athlete who didn’t deserve to be happy, and who didn’t love himself, making it hard for him to love anybody else.

In Baton Rouge, Miles noticed those same flickers as Collins once had, only they were happening more often and more intensely, as Mathieu flipped between who he was and what he wanted to become. Mathieu was one of the most versatile players Miles ever coached. On the field, he returned punts, intercepted passes, jumped over blockers, patrolled the secondary, sacked quarterbacks and forced fumbles. He claimed the Chuck Bednarik Award as the nation’s top defender in 2011 and that fall earned a rare invitation for a defender to the Heisman ceremony. With his distinctive blond hair and unforgettable Honey Badger nickname, Mathieu—a defensive back—became the most recognizable player in college football.

The following August, though, Miles kicked Mathieu off the team. He’d failed too many drug tests—at least 10, according to media reports—broken too many rules. “It was the hardest thing I ever had to do,” the coach says. Mathieu was never late, never lazy, never a distraction on the field—he just couldn’t stay out of trouble off of it. When Miles booted him, he stayed silent. He knew.

In the 2013 NFL draft, Mathieu plummeted all the way to the third round. He tore his left ACL that rookie season, busted a thumb in Year 2, tore his other ACL in Year 3 and separated his right shoulder in Year 4. Four seasons, four injuries, 16 games missed (including playoffs).

He started to doubt himself more deeply; the feeling bolstered when the Cardinals drafted his replacement and then cut Mathieu following the 2017 season. The Texans signed him for cheap and discarded him after one year. At times he wondered whether football was really for him; he considered what a different life might look like. He questioned whether anybody really loved him and, he admits, sabotaged much of the support he got.

“Most people would say I’m too good to be on my third team,” he says. That’s true. And yet, there he was.

For years, Mathieu wondered why he always had to take—or had always taken—the hardest route. Breaks never seemed to fall his way. Why did he hold onto (or pick at) so many wounds?

* * *

Mathieu cannot pinpoint his exact low point. The nadir didn’t result from checking into rehab for marijuana use in 2012. Or when he spent a night in jail on a marijuana charge and had his cellmates tell him to look around, that he didn’t belong there. Or when he showed up at McNeese State later that year, hoping to transfer, dressed to display disengagement: a stained tank top and shorts.

Each time, he told himself the same thing. Something’s gotta change. I can’t live like this anymore. I’m wasting my potential. Even then, he never could sustain progress. There were always fits and starts.

Looking back, Mathieu says no one had ever taught him how to process his emotions. Or build and sustain healthy relationships. Or express empathy and gratitude. Upon his arrival in Arizona, in 2013, he sought guidance, trying to take control of his life away from football, hoping that might correct his path. He met Donny Starkins, a mindfulness coach and yogi who had worked with the Phoenix Suns and other pro athletes, and said, “I’ve been looking for somebody like you.” He saved the contact in his phone as Donny the Yogi.

Donny the Yogi had played college baseball at Nebraska and Arizona State. He, too, had sustained injuries, endured surgeries, suffered from addiction and sought meaning, identity and purpose. Early in their conversations, he and Mathieu dove deep into an important but elusive concept for the safety: self-love. Donny the Yogi encouraged Mathieu to find his center, first by understanding all the baggage he carried with him, and then through yoga and meditation, which would help him to let go. He tried to disabuse Mathieu of the notion that football alone made him worthwhile and helped him to focus, eliminate distractions, breathe. “Happiness,” he said, “is an inside job.”

Progress wasn’t linear. Mathieu earned first-team All Pro with the Cardinals in 2015. He dropped the Honey Badger nickname and started most mornings with meditation sessions outside in the desert sun. But the injuries exacted a new psychological toll. Lee-Collins visited after the second ACL tear and says: “I saw how it was weighing on him. He was doing everything right, and then—Bam!”

Mathieu plunged deeply inward, holding a magnifying glass to his battered soul. He went to therapy and drew praise from Cardinals coaches for his leadership. He became vulnerable in ways teammates never could have expected, sharing his story and his path—and how he took back control. He became a walking self-help book, its dust jacket covered in scars.

After the second knee tear he started visiting Suneil Jain, a naturopath who believes in treating the body as a whole. Jain studied what he calls Mathieu’s metabolic deficiencies and changed the safety’s diet. He deployed Western and Eastern and homeopathic methods and discouraged medicine except in extreme instances, instead focusing on acupuncture and non-traditional therapies to, as Jain says, “re-align the body and make him as pliable as possible.”

Mathieu also heard from a local pastor, Scott Savage, over Twitter—Savage asked him, “Are you going through something?” And Mathieu, in his increasingly urgent pursuit of meaning and affection, responded to the stranger. He was going through something—Mathieu’s grandmother, Marie Spellman Mathieu, always the most stable force in his life, fell ill and passed in the spring of 2016. The two men bonded over grief and the safety started attending church. Savage helped to unravel the trauma, peeling deep. One day Mathieu pulled up his left pants leg and revealed the names of 20 of his closest friends, all dead before Mathieu himself had left for college—the torture tattooed across his lower half.

Mathieu was still processing all of that, but now he had the help of his own Three Wise Men—the pastor, the naturopath and the yogi. He began to see himself in different mirrors. As a present father of three children. As a stable, positive force. He still screwed up—“all the time,” he says—but the tools he was learning kept his emotions largely in check, including when he was released or passed over. After the Texans chose not to re-sign him, following the 2018 season, he thanked coach Bill O’Brien for what he’d learned, for the ways O’Brien had pushed him to lead. In Houston he had been named captain in a matter of months, becoming a stable force and positive impact.

That spring, Mathieu weighed his options. The Chiefs’ defensive coordinator, Steve Spagnuolo, reached out to O’Brien, who told him, “This guy changed the culture here the day he walked through the door.” When Kansas City signed the safety to a three-year, $42 million deal, Veach named Mathieu—the same guy who’d been kicked off his team and left school, gone to rehab and jail, and battled injury after injury—“the catalyst.”

Each morning, Mathieu would meditate and tell himself: Stay in balance.

* * *

In K.C., Mathieu and Spags bonded immediately. Perhaps that started with flattery. The coach told his new safety that he evoked Brian Dawkins, the Hall of Famer he oversaw in Philadelphia. He said, “You’re the guy I always wanted to coach,” and promised he wouldn’t move Mathieu all over the field, like others had. He wanted Mathieu to play free safety—to roam on instinct, blitzing regularly.

His coordinator’s belief meant everything to Mathieu. His belief in himself meant even more. He fit well in Kansas City—a homebody who loved football and barbecue and carried an ethos of everyman toughness, having lived a full life over 28 years and yet continuing to move forward. City, team and fanbase loved him back; they’d seen elite defenders in recent seasons, but never one like Mathieu, who claims, “I do things no other safety does.” He would tip the Chiefs over the edge, one way or another.

For a while, though, the franchise’s 2019 season took a turn toward mediocrity. Injuries piled up, with Mahomes playing through a bum ankle early and later missing TK games after dislocating his kneecap. When slot corner Kendall Fuller joined the QB in the training room, with a busted thumb in Week 6, Spags had to undo his promise, moving Mathieu all over the field, like the queen on a defensive chessboard.

Mathieu can pinpoint the exact weekend the season was saved. The Chiefs were 6-4 in mid-November, headed to Mexico City to play the Chargers. The safety believed his teammates were making too many excuses, starting with Mahomes’s injuries, but they were also banking on the eventual coalescence of a revamped defensive unit. Finally, he and Spags addressed the group. The time had come, they said, to eliminate all the explanations and justifications. Just play ball.

The Chiefs turned inward, like their safety. They topped the Chargers, healed up over the Week 12 bye and never lost again. Mahomes rounded back into MVP form, and the defense, led by Mathieu (75 tackles, two sacks, four picks and 12 pass break-ups), defensive tackle Chris Jones and edge rusher Frank Clark, sparked a late-season surge. A unit that ranked 31st in total defense in 2018 was suddenly among the most feared in the league, allowing an average of 11.7 points over the last seven weeks, sometimes winning with stout D rather than typically prolific Mahomes performances. “A lot of our wins weren’t pretty,” concedes Mathieu. “But if you took our logo off the helmet and put another team’s on, you would have said we were dominant.”

For the first time since 2015, Mathieu was named All Pro, but his impact stretched beyond anything measured by stats or awards. Down 24-0 to the Texans in the divisional round, he ran up and down the Kansas City sideline, imploring teammates to look across the field. “You should’ve seen them,” he says of his old Houston teammates. “Pom-poms, popcorn … They thought the game was over, man. I wanted my teammates to smell that blood.” Of course, he had been up when the team was down, thriving in discomfort yet again.

The Chiefs came back, toppled the Titans and Mathieu zoned out afterward onstage.

“You have to see the moment,” he says months later, echoing his mindfulness coach, “in order to really seize it.”

* * *

The newly-spiritual safety carried that Zen with him to Miami for Super Bowl LIV, and he brought his Three Wise Men along too. Jain performed daily acupuncture and alternative therapy sessions. Savage lent emotional support. And in addition to yoga and mindfulness sessions Donny the Yogi shared a 13-minute-long mindset visualization audio file, telling Mathieu things like “tune in to the quality of your breath” and “step into that version of you that’s 100% committed to showing up Super Bowl Sunday” and “make a picture, if you will, of a future you: focused, grounded and ready for all four quarters.” Mathieu listened to this “mental rehearsal” the night before the game, and again before he sprinted onto the field.

Against the 49ers, with their endless options, Mathieu figured the offense would throw and run away from him, but still he visualized making plays, as he always had. Notice that your entire body is filled with fresh energy, and the world appears more beautiful than ever. … You can see with more clarity. … You can feel yourself more alive. … You’ve never seen more clearly. … You’ve never been faster. … You’ve never felt better. … You are fully immersed in this moment—right here, right now.

At Hard Rock Stadium in Miami, as Mathieu trotted out onto the field for warm-ups, Del Lee-Collins held onto his old player’s one-month-old daughter, Mila, and allowed himself to look back on the path to the pinnacle, on the love-hate turned pure love.

On the field, he watched as the Chiefs fell behind. The 49ers did steer their offense away from Mathieu, but three of the tackles he made arguably saved touchdowns. He kept his teammates communicating as they fell behind, kept them talking and staying present, even if the scene may have looked like a sideline freakout on TV. In actuality, Mathieu was pleading with his teammates to stay calm.

After the comeback and the victory, the same player who was thrown off his college team for drug use—who went to rehab—steered clear of the championship party. Mathieu hung out with family and friends and a yogi and a naturopathic doctor at his hotel instead. Watching that all unfold, Lee-Collins says, “All I saw was growth.”

Asked what that moment represented to him, Mathieu pauses for five seconds. Finally, he says, “I don’t know, man. Like I knew we won the Super Bowl, but I still didn’t feel like I had that respect. I felt like: Now I gotta do it again.” Of course, he was now down when the team was up, the lack of chaos twinned with his lack of satisfaction, fueling the next round of introspection, and the next round of growth.

* * *

On the night Mathieu first became aware of the video footage that showed a Minneapolis police officer killing George Floyd, he couldn’t bring himself to watch the whole eight minutes and 46 seconds. He looked at his three children, each under the age of nine, and worried about the toxic culture of the world he’d brought them into. “Being a black dude in America, [what happened to George Floyd] is something that we always knew was possible,” he says. “I feel for kids who have to grow up in that kind of world.”

Could he affect it? This summer, while sports were paused and protests forced America to again reconsider its terrible racial history, Mathieu, now 28, took a call from Michael Thomas. The Saints wideout wanted to make a video featuring some of the most prominent players in the league, and he wanted them to push the NFL toward recognizing the Black Lives Matter movement, to acknowledge that players have a voice and to encourage them to speak.

“I’m all in,” Mathieu replied.

Neither player felt that the league had sufficiently responded to Floyd’s killing. And Mathieu, specifically, believes the NFL did wrong by Colin Kaepernick. He says the former 49ers quarterback was “blackballed” for his social conscience, for wanting to address systematic racism and widespread inequality—issues that continue today. With that in mind, he sent text messages, hopped on FaceTime calls and became a salesman for Thomas, helping to recruit for the video Cardinals receiver DeAndre Hopkins and cornerback Patrick Peterson; Texans quarterback Deshaun Watson; and Mahomes, the emerging face of the league. “Pat was important,” Mathieu says. “Huge.”

The video came out, spreading quickly all over the world. Commissioner Roger Goodell responded on Twitter, using the phrase “Black Lives Matter” and acknowledging that players had the right to protest obvious wrongs—a full pivot from the league’s stance when Kaepernick started kneeling in 2016.

In Kansas City, the events following Floyd’s death inspired conversations among teammates, and Mathieu, having found a focus outside of football, was at the forefront. Owner Clark Hunt called up him and the other captains, and Mathieu dove right in, hammering the lack of minority coaches across the league and stressing the importance of Black voter registration. Hunt, Veach and coach Andy Reid organized Zoom calls for the entire team, and no one mentioned football. Instead, Black players detailed their life experiences to white executives, and for weeks this went on, even in position meetings.

“A lot of times when they’re paying you millions of dollars, it’s like, All right, get to work,” Mathieu says. “Here, it seemed like football took a backseat. You could feel the intensity, the passion. [People] wanted to understand.”

Mathieu was not new to activism—he’d started a foundation to help disadvantaged children, submitted himself to being locked in a hot car for a PETA campaign, and donated 30,000 meals to Kansas City families after COVID-19 spread. As the world protested, in the wake of Floyd’s death, he donated money and helped secure speakers for an organization that mentors at-risk youth around New Orleans and Baton Rouge. He continued to promote Black Lives Matter dialogue within the Chiefs organization, speaking regularly with Hunt and other decision makers. This, perhaps as much as hoisting the Lombardi Trophy, gave him a sense of fulfillment, a dual purpose. “I feel myself tapping into [activism] more as I get older,” Mathieu says. “That’s how you make the world better. That’s how you create change.”

As Savage, the pastor, watched Mathieu act on their conversations, he told anyone who’d listen that they needed to know two things about the safety formerly known as Honey Badger. One: He’d lived through more pain than anyone Savage had ever met. And two: He was the most generous person Savage knew.

“In essence, he created what he had always needed,” Savage says. “Stability. Empowerment. Positive influences. And now he’s giving to other people what nobody ever gave to him.”

* * *

Savage says that Mathieu hardly celebrated after the Super Bowl because he no longer needed to. He no longer defined himself by football alone.

On the Super Bowl stage Mathieu again found himself next to Kelce and Mahomes. Only this time, amid another confetti shower, no one mentioned a dynasty. They didn’t have to.

Earlier this summer, Mathieu pestered Veach, telling him to keep the Chiefs intact. When he saw Mahomes sign a contract in July that could earn him half a billion dollars, he tapped out a few text messages. To the GM: “Yo, bro, you really just did that.” Then, to the QB: “I don’t believe you know how special you really are.” Finally, he exchanged a few notes with Reid, who tapped back, “Man, if I have you and Patrick, I can coach until I’m 90.”

The safety stayed home in Kansas City these past few months, like he would have even without a pandemic. He even set up a yoga area in the basement where he can meditate and work out. If the season starts on time, he plans to play. It’s not his job, he says, to assess the risk. (He also notes that, in his career, he has already missed a full season’s worth of games.) “It’s all about keeping the balance,” he says, “staying positive, not feeling overwhelmed.”

Sometimes Mathieu will probe his coaches for tips on how to maintain last season’s success. They’ll tell him that a dynasty—like happiness or a career resurgence—“is an inside job.” This spring and summer, as the pandemic unfolded like an apocalypse and racial unrest defined an unstable America, Mathieu used the turbulence to fuel his preparation to make good on all the dynasty talk. In discomfort, he had found his Zen. Now, the world is anything but settled, and Tyrann Mathieu, of course, feels grounded, stable and at peace.